“We don’t know nothin’ but what we see . . .” —Zora Neale Hurston

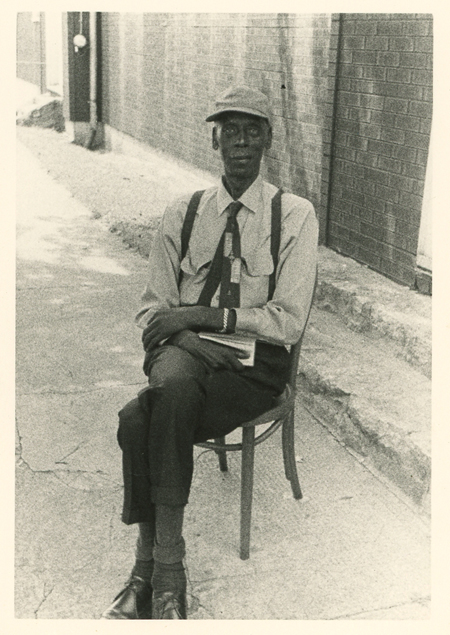

After her mother Jeroline Rice passed in 2003, Marian Waters sorted through boxes of photographs that her father Isaiah Rice had taken over the course of his adult life. Rice, who died in 1980, had taken hundreds of photographs of family, friends, and strangers in his Asheville, North Carolina community. While Waters always knew her father loved photography and would go everywhere with his cameras, she laughed to remember how some people in the community joked that he was like a spy with that tiny camera he owned, even taking it to church on Sundays. He was a proud man who knew how to remain invisible when he needed to take a picture.

Waters considered discarding the photos her father had taken of people she did not know, but she shared them first with her son, Darin Waters, a scholar of American and African American history, who immediately recognized the importance of the more than 1,000 vernacular photographs taken by his grandfather. He shared Rice’s photographs with Gene Hyde and Ken Betsalel, colleagues at UNC Asheville, who agreed that Rice’s photographs provided fresh insight into the unique cultural context of an urban African American community in southern Appalachia.

He was a proud man who knew how to remain invisible when he needed to take a picture.

Rice’s photographs of Asheville draw some comparisons to other photographers who were working in the city at the same time. The largest and best known Asheville area photographic collection is the E. M. Ball Photographic Collection, which contains the work of professional photographers Ewart M. Ball Sr. and his son Ewart M. Ball Jr., as well as several photographers who worked for the Balls’s studio. The Ball Collection, housed in Special Collections at UNC Asheville, contains over 11,000 photos and negatives and includes their work as both contract photojournalists for the local newspaper and as professional studio photographers. Although it documents Asheville over half a century, it contains only a handful of photographs of African Americans. What makes the Rice Collection uniquely valuable is that Isaiah Rice’s photographs document a wide range of subjects, from his own Burton Street neighborhood, where he was known as “the picture man,” to the wider Asheville communities through which he traveled.2

“There are few Negroes”?

Isaiah Rice (1917–1980) was born in Asheville, North Carolina, to Theodore and Alberta Rice. A loving family man of deep faith, conviction, and responsibility, he married Asheville native Jeroline Bradley Rice in 1942, and they had one daughter, Marian Waters. He was educated at Stephens-Lee High School and made the best of opportunities available to him, including working for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression. Rice was drafted into the U.S. Army, and worked as a beverage deliveryman for a local distributor until his death in 1980. He was well known in the African American community and faced the daily humiliations and limitations of racial prejudice and segregation by creating strong community bonds.

Rice made his photographs during the post–World War II era of uneven national economic development, continued racial segregation, the ongoing fight for civil rights and racial equality, and the subsequent years of suburbanization and urban renewal in Asheville. When Rice was taking his photographs during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, Asheville’s African American community constituted a sizeable portion of the city’s population. The 1950 Census reports that 12,723 “nonwhite” people lived in urban Asheville, which amounted to 21.8 percent of the city’s population. By the 1960 census, the “nonwhite” population was 12,504, or 18.2 percent of the city’s population, and by 1970, Asheville’s “Negro or other races” population was 10,671, or 18.5 percent of the total urban population. In contrast to the African American population in urban Asheville, 1970 census figures for ten rural mountain counties near Asheville show an average African American population of 3.4 percent, with the closest Appalachian urban area to Asheville—Knoxville, Tennessee—at more than double that at 7.8 percent of the population. Even as African Americans made up a sizable percentage of the population in cities like Knoxville and Asheville, outside of urban centers African American populations were smaller. This aided a general perception that the African American presence in Southern Appalachia was minor, which neatly elided into the view that the social impact of African Americans in Appalachia was minor.3

Writing in 1962, sociologist John C. Belcher, who examined the region’s racial demographic as part of the work surrounding the development of the Appalachian Regional Commission, stated that “the number of Negroes in the Appalachian Region is such a small proportion of the total population that the social consequences of their presence and migration are not of any great significance.” The trope of African American “insignificance” in the region, especially in its post–Civil War formulation, has its roots in the scholarship of John C. Campbell, a pioneering scholar of Appalachian Studies. Writing in his oft-cited The Southern Highlander and His Homeland (1921), Campbell argued that while there were more blacks in the southern Appalachian Mountains than one might expect, the “often repeated statement that there are no Negroes in the mountains” is generally true. “In many of the remoter counties, especially those where there are few large valleys, few mining or industrial developments, or few cities,” Campbell wrote, “there are few Negroes.”4

This influential assertion went unchallenged for more than half a century, until the publication of the multi-disciplinary anthology Blacks in Appalachia in 1985. In the introduction to this collection, sociologist William H. Turner observes that the failure to study African American history in the region has left us with an incomplete picture. While it cannot be denied that scholarship on the black experience in Southern Appalachia has come a long way since the anthology’s publication thirty years ago, documentation of the day-to-day life of Black Appalachians remains far too fleeting, too impressionistic, and too reliant on white sources. One of the greatest challenges to uncovering the black experience is the paucity of sources, particularly those that depict life from the perspective of African Americans. As a result, it has been difficult to construct narratives that center African American Appalachians in their own story.5

Documentation of the day-to-day life of Black Appalachians remains far too fleeting, too impressionistic, and too reliant on white sources.

Rice’s photographs bring African American Highlanders squarely into subjecthood, thus challenging the presumption of African American historical “insignificance” in the region and complicating notions of Appalachian homogeneity. When we examine Rice’s work in the context of Appalachian photographers (or photographers of Appalachia), both historical and contemporary, his work does not fit into the well established categories. Upon first viewing, Rice’s photographs do not appear to capture the themes of social and economic injustice depicted by the Farm Security Administration documentary photographers during the Great Depression, nor the faces of hunger and unemployment as documented by John Dominis in his 1964 Life magazine cover story on Appalachian poverty, nor do they record the African American struggle for civil rights. However, a deeper read of Rice’s photographs suggests that the very act of taking pictures with a camera, no matter how small, was a form of resistance. As political theorist Danielle S. Allen reminds us, photographs made during the period of racial segregation cannot but help to call attention to “two sets of rules . . . that secured stable (though undemocratic) public spaces.” Rice’s photographs, in this context, can provide a “new frame” in which to scrutinize “two etiquettes of citizenship” that bounded the black and white public spaces he moved through. From this perspective, Rice’s photographs have the power to make visible the structures of a society divided along the color line.6

And while the region’s notable contemporary photographers have varied perspectives and subject matter, their focus largely has been on rural and white populations, as exemplified in the work of Earl Palmer, Shelby Lee Adams, and Rob Amberg, as well as Earl Dotter and Builder Levy, who document coal miners and their communities. There are many other Appalachian photographers, of course, but none known to have documented their own African American communities so extensively. Rice’s photographs, unique in depicting the daily lives of ordinary black people in a mountain city, are evidence of a more complex and diverse region.7

“In-between and above and below”

An enthusiast with considerable commitment to photographing life as he knew it, Rice produced “urban folk photography” in the vein of the vernacular photography of the era, including Eudora Welty’s photographs of everyday folk in Mississippi, Louisiana, and North Carolina; Helen Levitt’s street photography in Harlem; and Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s now classic Sweet Flypaper of Life, also focusing on Harlem. Rice’s photographs also find complements in the work of Paul Kwilecki, who documented life in his home town of Bainbridge, Georgia; Vivian Maier, whose passion for photographing life in the streets of Chicago went unrecognized for years; and self-taught African American photographer Richard Samuel Roberts, who made portraitures of the urban African American community in his Columbia, South Carolina studio.8

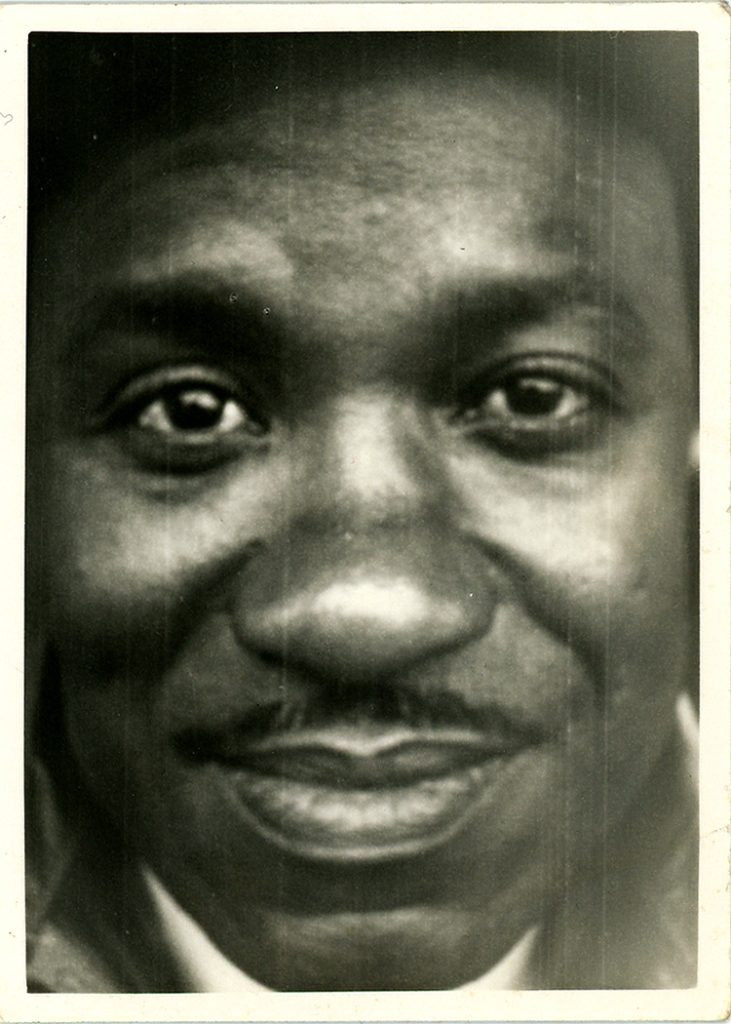

Rice’s body of work shares with these works a quiet lyricism and joy, as well as depicting the loneliness and melancholy of urban life. But it is Zora Neal Hurston’s “unvarnished” look at African American folk life in the rural Southeast that perhaps best captures Rice’s ethos. As Hurston explained in a 1944 interview, “There is an over-simplification of the Negro. He is either pictured by conservatives as happy, picking his banjo, or by the so-called liberals as low, miserable and crying. The Negro life is neither of these. Rather, it is in-between and above and below these pictures.” It was precisely this “in-between and above and below” of black daily life that Rice was able to capture in Asheville, calling to mind too James Agee’s desire to faithfully document “how each of you is a creature which has never in all time existed before and which is not quite like any other.” There are no “others” in Rice’s photographs, only subjects of human particularity. In these enfranchising photographs, Rice quietly brings into focus citizens that had heretofore been unrepresented.9

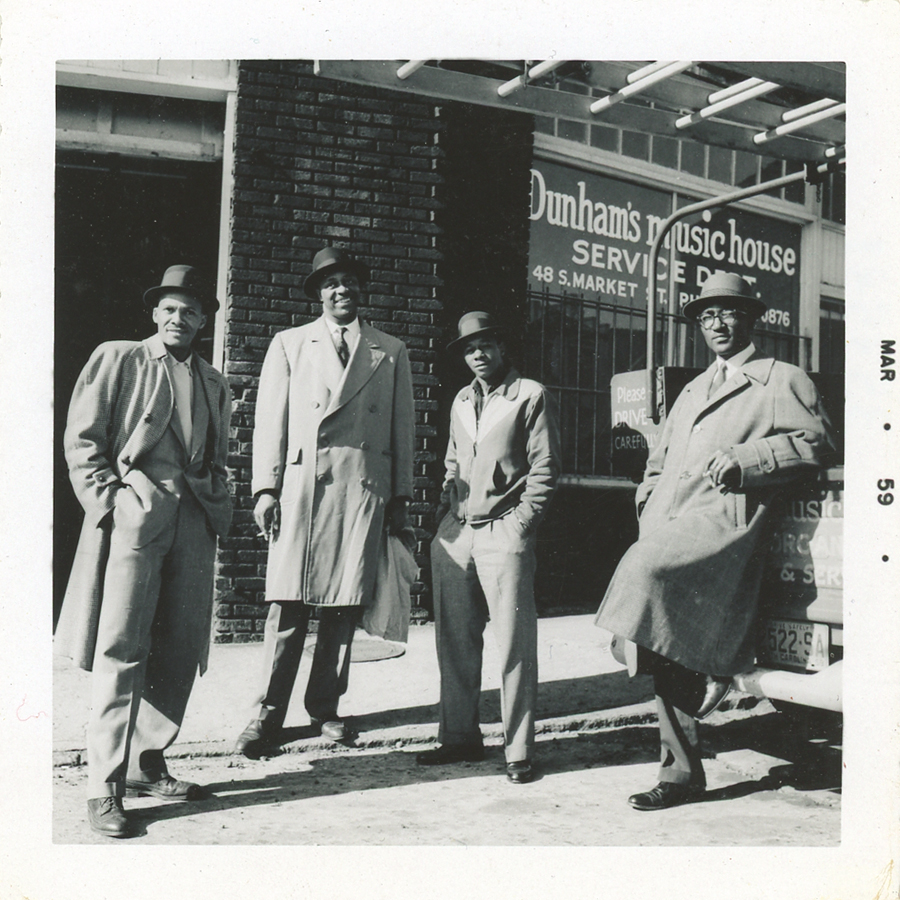

The depth of Rice’s passion for photography is evidenced in his choice of camera equipment and a body of work totaling well over 1,000 prints, slides, and negatives. In an era of Brownie instamatics, Rice owned several cameras and favored German cameras produced in the 1950s and 1960s. He took slides and prints with a Zeiss/Ikon Ikoflex Ic 886/16, a twin lens reflex camera that was produced from 1956 to 1960 and cost $146 when it was first introduced. Rice also owned an Ansco Speedex 4.5 (which retailed for about $47 in 1955), a Kodak Duaflex, and a Polaroid camera. Perhaps the most intriguing camera was his Minox-B subminiature “spy” camera, which was produced from 1958–69 and cost around $160 in 1969. It is approximately 3 ¾” x 1″ x ½”—about the size of a pack of gum—and the negatives were a tiny 8mm x 11mm. Its diminutive size made it perfect to carry in a pocket or small pouch, and made it easy to take photos without drawing attention to the photographer. Adjusted to today’s prices, Rice paid the equivalent of nearly $3,000 for his cameras, suggesting that he was very serious about his avocation.10

“A transformative act”

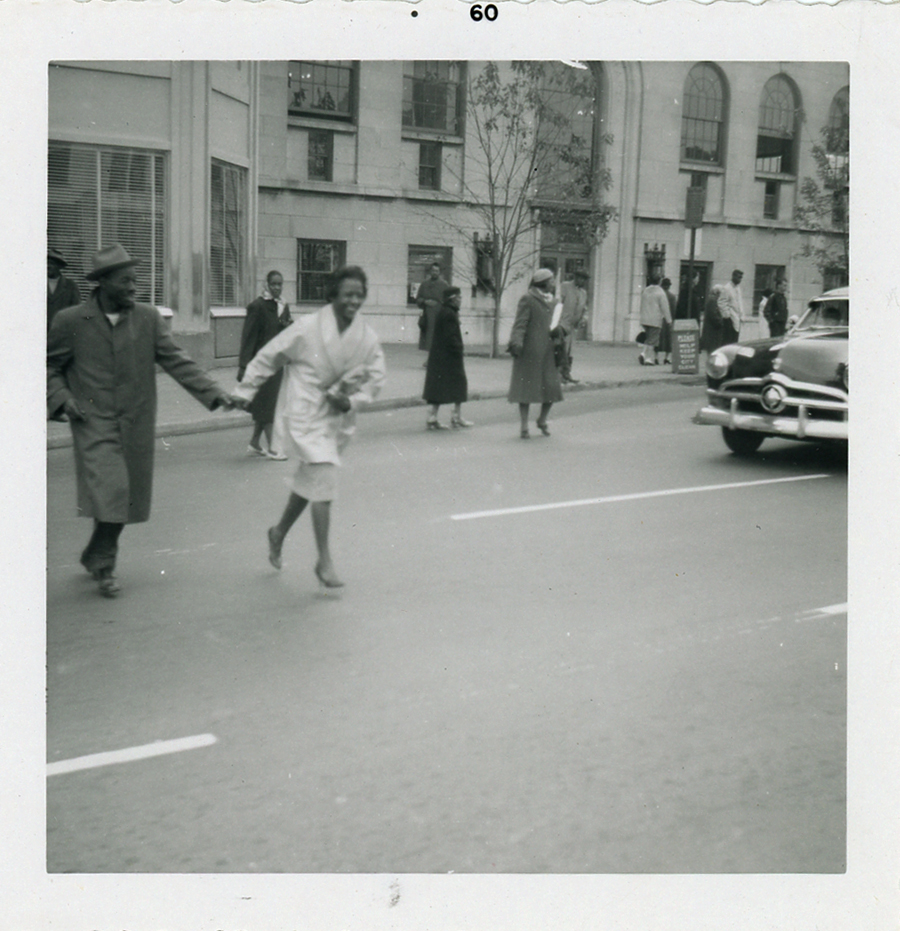

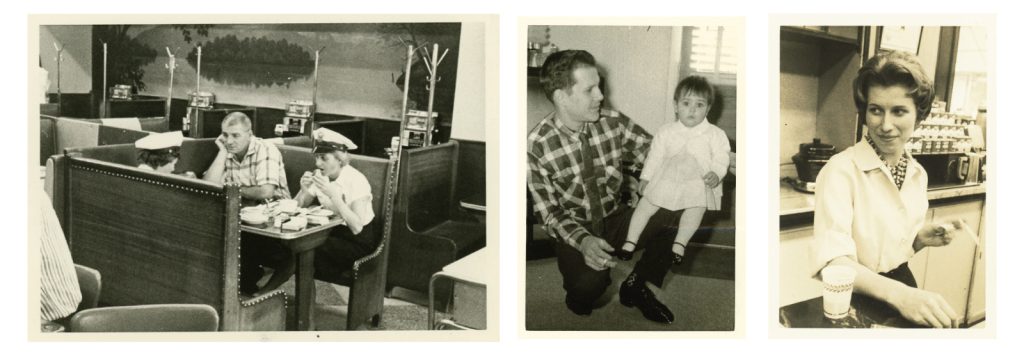

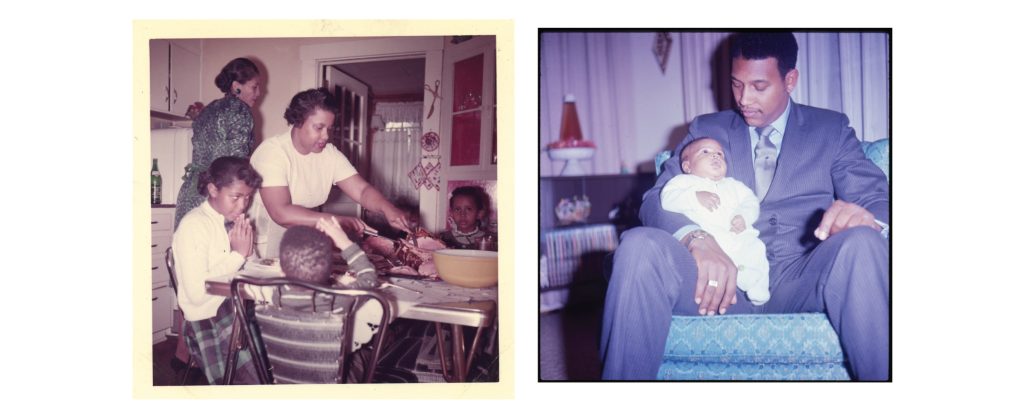

The images selected for this essay focus on what might represent a day in the life of Isaiah Rice as he journeyed through his city, crisscrossing the color line of black and white, photographing friends, family, strangers, and whatever else he deemed important. While Rice may not have thought himself an artist, his way of seeing reveals a style that is self-aware and serious, connected to his community, while at the same time playful and direct, even when he was “secretly” taking pictures in plain sight. There is clear excitement, even a sense of freedom, in Rice’s photography—and a palpable joy in image-making. On his delivery route or on foot, Rice photographed what pleased him. His subjects clearly knew who he was, and often a photo taken through his truck windshield would show smiling, laughing people at work and play in Asheville’s city streets, greeting their neighbor Isaiah and his camera.

There is clear excitement, even a sense of freedom, in Rice’s photography—and a palpable joy in image-making.

Rice’s photographs include family and friends, his church, schoolchildren, pets, still lifes, and portraits. He had a passion for parades, street life, and men and women at work, although he was also capable of creating stunningly quiet portraits. Together, these photographs form a kind of family album. Photographer, historian, and curator Deborah Willis has said she was “intrigued” as an artist how her own family album could be used to creatively represent African American history and culture, observing that

The photograph is an instrument of memory, one that explores the value of self, family, and memory in documenting every day life. Photographing friends, family members, and objects is a transformative act, one that can instill a sense of joy and dignity in both the photographer and the subject. Since the beginning of photographic history, family photographs have had a special connection to the viewer.

What is unusual in the Rice photographs is that we have a near complete family album, but one that extends beyond family members to those living in the immediate and extended community.11

“Welcome to Our City”

At the time Rice was photographing, Asheville was a de facto segregated city. African American neighborhoods were “redlined” by realtors and banks as being less desirable for home mortgages and businesses loans. There were six distinctly African American neighborhoods in Asheville: East End (associated with downtown Asheville), South Side, Stump Town, Hill Street, Shiloh, and, across the French Broad River in West Asheville, the Burton Street Neighborhood, where the Rice family lived. The “Area Description Form” that accompanied Asheville’s 1937 Redlining map designates the Burton Street neighborhood as of the lowest investment quality (“Area D3”), and describes it as “100%” inhabited by “Common laborers and tannery workers and negro railroad laborers” and as having “inadequate transportation, unpaved streets,” and “quite a few foreclosed properties owned by lending agencies.” In the report’s “Clarifying Remarks,” it notes, “Some properties of uniform construction built in this area by white owners for investment purposes.”12

Developed in 1912 by African American civic leader and businessman E. W. Pearson, the Burton Street neighborhood pictured in Rice’s photographs appears more rural than other African American neighborhoods in Asheville. Pearson, himself a longtime Burton Street resident, was the president of the Asheville chapter of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association and a founding member and president of the local chapter of the NAACP. Burton Street was considered a black working class neighborhood where black home ownership was possible. The neighborhood included 116 African American households, five churches, two grocery stores, a grammar school (later a community center), two night clubs, a coal and ice company, and several barber shops and beauty parlors.13

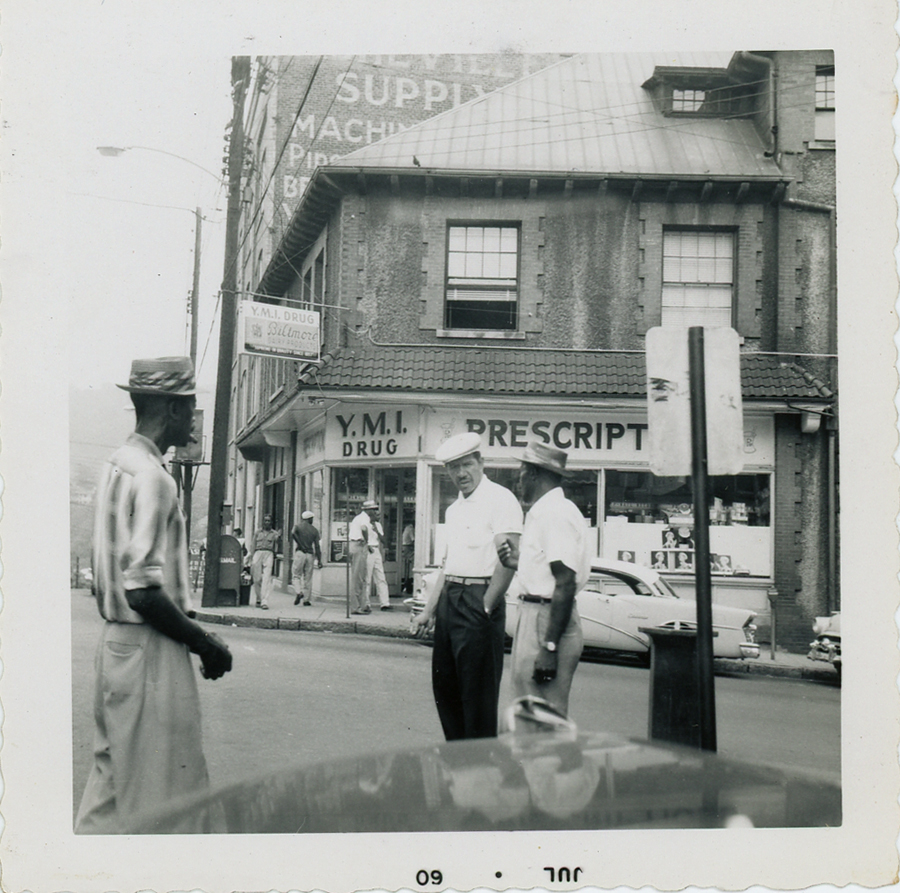

It was from this neighborhood that Rice would venture “downtown” into the city. Taking aim with his Minox through the window of his delivery truck, he would document life as he saw it. His delivery route would often take him past the African American YMI Culture Center, Drug Store, and Soda Shop on 37 Market Street, the heart of the East End African American neighborhood. Located behind the Asheville Police and Fire Departments, the Eagle and Market Street area was home to many African American businesses, including the Savory Hotel and Café, Roland’s Jewerly, Club Del Cardo, and the Ritz Restaurant. Near to these business were African American homes, churches, and schools. The WPA 1937 guidebook for Asheville described the African American community Rice would later drive through this way:

The 14,255 Negroes in Asheville, 28.4 percent of the total population, maintain a business center on Eagle and Valley Streets and another on Southside Avenue. The better Negro homes are on the east end of College Street and on streets in the north central part of town. While the bulk of the race is employed in unskilled and domestic labor, the Negroes are represented in most of the professions as well as in business. They have their own churches and schools, including the fully accredited Stephens Lee High School.

Asheville native Thomas Wolfe would write about this area of the city in his 1922 play “Niggertown,” later retitled “Welcome to Our City.”14

“To catch the shadows of the color-line”

Rice traversed both black and white neighborhoods in his work, navigating a color line that was not always bright but “you knew it when you crossed it.” (Asheville would not begin to desegregate until the closure of the famed Stephens Lee High School in 1965.) One of the few places where black and white Ashevillians came together was when they lined up to see a city parade. As writer and historian W. E. B. DuBois eloquently described his own experience of the color line in Atlanta, Georgia:

Slowly but surely his eyes begin to catch the shadows of the color-line here he meets crowds of Negroes and white; then he is suddenly aware that he cannot discover a single dark face; or again at the close of a day’s wandering he may find himself in some strange assembly, where all faces are tinged brown or black, and where he has the vague, and uncomfortable feeling of the stranger. He realizes at last that suddenly, silently, resistlessly [sic], the world about flows by him in two great streams: they ripple on in the same sunshine, they approach and mingle their waters in seeming carelessness—then they divide and flow wide apart.15

Rice’s photographs powerfully capture the way the world about him both “mingle their waters” and “divide and flow wide apart” along lines of race. There is a respectful distance in a Rice photograph, a sense of in-betweenness, and a sense of seeing the world as it is.

Much of this world would begin to shift with suburbanization and Urban Renewal projects begun in Asheville in the late 1960s. While other photographic collections importantly document African American experiences of struggle and protest, the photographs Rice took in his Burton Street home, and sometimes in the homes of his neighbors, are significant in depicting a “family album” of extraordinary ordinary beauty, in a place where many continue to fail to see their presence and contribution to life in their region acknowledged. Rice photographed family and friends, strangers and co-workers, whites and blacks with a photographer’s eye, alive with human particularity and dignity. He crisscrossed the color line, honoring his subjects and investing them with dignity, and in this way complicated our view of race in Appalachia. The stories of African American highlanders, both rural and urban, are yet being written, but the donation and digitization of photographs taken by Asheville native Isaiah Rice will go a long way in advancing a deeper understanding of Asheville, the region, and the experiences of its African American communities in particular. They remain a family album for all of us.

This essay was first published in the Appalachia issue (vol. 23, no. 1: Spring 2017).

Darin J. Waters is Assistant Professor of History and Special Assistant to the Chancellor at the University of North Carolina at Asheville where he teaches courses in American history, North Carolina history, Appalachian history, African American history, and Latin American history. Dr. Waters also specializes in the history of race relations both in the United States and Latin America.

Gene Hyde is the head of Special Collections and University Archivist at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. Mr. Hyde holds MAs in library science and Appalachian Studies. His research investigates the role of special collections in Appalachian studies research and curricula.

Kenneth Betsalel is Professor of Political Science at the University of North Carolina at Asheville where he teaches courses in American Political Thought, Civic Engagement in Community, and ReStorying Community. Over the course of his career Dr. Betsalel has used documentary photography in his teaching and scholarship.

- (Opening pull quote) Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (New York: Harper, 2006), 14.

- Isaiah Rice Photograph Collection, D. H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804, http://cdm15733.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/search/collection/p15733coll11. Images copyright Darin Waters. Prior to the donation of Rice’s photographic collection to UNC Asheville in 2015, the sources of photographs pertaining to the African American community in Asheville included those found in the North Carolina Collection held at Buncombe County Pack Library and the Heritage of Black Highlanders Collection held at the D. H. Ramsey Library Special Collections at UNC Asheville. Two other collections of photographs of the African American community taken in the late 1960s are Andrea Clark’s “East End Asheville Photographs Circa, 1968,” held at Pack Library’s North Carolina Collection, and the Kent Washburn “Urban Renewal Photographs,” held at the Asheville Art Museum. Andrea Clark’s work can be seen in her book, East End Asheville Photographs Circa 1968, http://library.digitalnc.org/cdm/ref/collection/booklets/id/29992, accessed September 12, 2016. A portrait of Asheville’s East End neighborhood and Asheville’s African American communities can be found in “Twilight of a Neighborhood,” in the Summer/Fall 2010 issue of the North Carolina Humanities Council’s Crossroads magazine, http://www.nchumanities.org/sites/default/files/documents/Crossroads Summer 2010 for web.pdf, accessed September 5, 2016.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Characteristics of the Population, North Carolina, 1950, http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/06586136v2p33.zip. Characteristics of the Population, North Carolina, 1960, http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/06586188v1p35.zip. Characteristics of the Population, North Carolina, 1970, http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1970a_nc.zip, accessed May 12, 2016, Characteristics of the Population, Tennessee, 1970http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/00496492v1p44.zip, accessed January 16, 2017. Note that the census terminology changed from “nonwhite” in 1950 and 1960 to “Negro or other races” in 1970.

- John C. Belcher, “Population Growth and Characteristics,” The Southern Appalachian Region: A Survey, ed. Thomas R. Ford (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1962), 152; John C. Campbell, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1921), 201.

- John C. Inscoe, Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 10.

- See the following: William Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986); Gordon Parks, The Photography of Gordon Parks: The Library of Congress Collection (London: Giles, 2011); Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992); and Civil Rights and the Promise of Equality: Photographs from the National Museum of African American History and Culture (London: Giles, 2015); Danielle S. Allen, Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship Since Brown v. Board of Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 4–5.

- Information about Appalachian photographers comes from several sources, including Builder Levy’s Images of Appalachian Coalfields (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989), The Appalachian Photographs of Earl Palmer, ed. Jean Haskell Spear (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990), Shelby Lee Adams’s website, http://shelby-lee-adams.blogspot.com/, Earl Dotter’s website, http://earldotter.com/, and David Whisnant’s review essay, “Sodom Laurel Again: A Response to Malcolm Wilson and Other Reviewers of Sodom Laurel Album,” Journal of Appalachian Studies 9, no. 2 (2003): 450–58. Of particular note when it comes to visually portraying Appalachia is Roger May’s Looking at Appalachia project, a crowd-sourced website designed to “explore the diversity of Appalachia” through presenting images submitted by both professional and amateur photographers in the region: http://lookingatappalachia.org/overview, accessed January 14, 2017.

- See the following: Eudora Welty, Eudora Welty: Photographs (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1989); Helen Levitt, A Way of Seeing (New York: Horizon Press, 1965); Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life (New York: Hill and Wang, 1967), and Eudora Welty As Photographer, ed. Pearl Amelia McHaney (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009); Paul Kwilecki and Tom Rankin, One Place: Paul Kwilecki: Four Decades of Photographs from Decatur County, Georgia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), John Maloof, Vivian Maier: A Photographer Found (New York: Harper, 2014), and Richard Samuel Roberts, A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts, 1920–1936, ed. Thomas C. Johnson and Phillip C. Dunn (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 1986).

- Robert E. Hemenway, Zora Neal Hurston: A Literary Biography (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1977), 299; James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1941), 100.

- Rice may have taken his film to be developed and printed by Ball Photography, a local watering hole for shutterbugs, or perhaps at one of the other half-dozen other camera stores in Asheville at the time. His Minox film required special handling, and was mailed to a Minox processing lab for developing and printing; Accurate information on older cameras can be difficult to find, and some of the prices may be approximations. Information on the Zeiss/Ikon Ikoflex was found at http://www.tlr-cameras.com/German/Ikoflex.html. Information on pricing for the Ikoflex found in a 1956 unidentified camera magazine ad on Pinterest. Information on the Minox B is from the Cryptomuseum website, http://www.cryptomuseum.com/covert/camera/minox/b/index.htm, and the Ollinger’s Camera Collection site, http://www.jollinger.com/photo/cam-coll/cameras/submini/70001-minoxb.html. Information on the ANSCO was found at the Scott Huck Photo blog, https://scotthuckphoto.wordpress.com/tag/camera/. Pricing adjustment were calculated using the Consumer Price Index inflation calculator, http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl. All sites accessed September 13, 2016.

- Deborah Willis, Family History Memory: Recording African American Life (New York: Hyla, 2005), 6, 157. The metaphor of family album as a way to tell the story of African American history and photography can also be seen in Thomas Allen Harris’s documentary film Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People, directed by Thomas Allen Harris, K. Period Media, First Run Features, 2014.

- See the essay by Sarah M. Judson in “Twilight of a Neighborhood” in Crossroads; Information on the Asheville redlining map can be found in David Forbes, “Red Lines,” Asheville Blade, http://ashevilleblade.com/?p=241, accessed December 16, 2016.

- Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Book 154, Page 141, Park View. North Carolina Collection, Pack Library, Asheville, NC, and “E. W. Pearson—Organizer,” The Southern News, ca. September 1937, North Carolina Collection, Pack Library, Asheville, NC; Miller’s Asheville City Directory Vol. XLV (Richmond, VA: Piedmont Directory Co., Publishers, 1950).

- Federal Writers’ Project of the Federal Works Agency, North Carolina: The WPA Guide to the Old North State. Reprint of 1939 edition. (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press), 138; Richard S. Kennedy, “A Note on the Text,” in Thomas Wolfe, Welcome to Our City (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1983), xi.

- Clifford Cotton Jr. (grandson of E. W. Pearson), interview with Kenneth Betsalel, May 18, 2016; W. E. B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk (New York: Dover, 1994), 110.