He who lives by the song shall die by the road. —Roger Miller (1)

Even before he became the “King of the Road,” Roger Miller reigned as the undisputed king of the dashboard poets. By his own recollection, he composed his first solo hit, “You Don’t Want My Love,” on the road from Fort Worth to Nashville. “Just driving along by myself,” Miller described the process, “sipping a little wine here and along the way [to] keep my spirits up.” His first top-ten hit, “When Two Worlds Collide,” came about in Miller’s Rambler station wagon during an all-night drive with Bill Anderson. “In those days we didn’t have these little tape recorders like you do now,” said Anderson, “so we had to stay up all night singing it to each other, all the way down there, so we wouldn’t forget it.” Miller’s classic ballad “Husbands and Wives” initially took shape, fittingly enough, while he and his wife were “driving down the freeway one night.” “I just started singing it,” said Miller, who wrote the rest of the song on a ride home from the Los Angeles airport with friend Don Bowman. “Thanksgiving Day, no traffic, it took thirty or thirty-five minutes, and he was humming and tapping on the dashboard,” said Bowman. “He didn’t say a word all the way there . . . [H]e got out and walked in the house, picked up his guitar and sang ‘Husbands and Wives.’” Then there was “King of the Road,” inspired by a sign (“Trailer for Sale or Rent”) that Miller saw hanging on the side of a barn one night on his way to Chicago. The song sold over one million copies and won him six Grammys in 1966.2

Some of my best writing, I think, is done when I’m driving down the highway by myself.

Miller’s only serious rival behind the wheel may have been his old friend and fellow traveler Willie Nelson, who reportedly wrote three hits—“Crazy,” “Night Life,” and “Funny How Time Slips Away”— over a two-week stretch as he drove back and forth, night after night, to a club on the other side of Houston. “Some of my best writing, I think, is done when I’m driving down the highway by myself,” said Nelson. “My mind is clear and open and receptive. Then something will happen . . . A song will start. The good ones come quickly, and then it’s over.” Like Nelson, Miller did some of his best work on the road, or some variation thereof, becoming perhaps the only person in the history of recorded music to write a top-twenty hit (“A World So Full of Love”) on the back of a riding mower. Call it highway hypnosis or some sort of equivalent meditative state, there was something about laying hands to the wheel that freed up the songwriter in his mind.3

Miller’s habit of dashboard composition—which also produced “Fair Swiss Maiden” and “Invitation to the Blues,” a number-three country hit for Ray Price—may not have been uncommon among traveling musicians of his day, most of whom were forced by necessity to write whenever and wherever they could find the time. But it’s all the more impressive considering Miller’s well-documented driving habits, which would qualify as erratic by any standard. As William Whitworth noted in his 1969 profile for The New Yorker, “Miller has the manual dexterity for driving but not the attention span. Every few minutes, bored with simply staring at heavy traffic, he would begin reading a note from his shirt pocket, examining the instrument panel on the dash, or checking to see what was tucked under his sun visor. [His drummer Jerry] Allison saved us from certain death three times by hollering at Miller just in time to get us off a collision course.” Whitworth wasn’t alone. Kris Kristofferson recalled a last minute dash to the Nashville airport during which Miller was literally “riding on the sidewalks.” Mel Tillis rode with Miller enough to know better than to let him take the wheel at all. “I wouldn’t let him drive,” said Tillis. “Hell, he couldn’t keep his mind on what he was doing. He was either thinking of songs or [women].” Of course, Miller was thinking about the road—at least as inspiration. In that way, he is like many songwriters before him and since, from Nelson to Woody Guthrie to his early idol, Hank Williams, who famously wrote the lyrics to “I Saw the Light” in the backseat of his mother’s car while she drove him home from a show in Fort Deposit, Alabama. For Miller, who grew up along the famous “Mother Road,” Route 66, thumbing his way from one honky tonk to the next, the road was an escape.4

As one of a large stable of Tin Pan Valley songwriters in Nashville who turned out songs by the hundreds for Music Row during the 1950s, Miller tried his hand at just about every type of genre (tear-in-my-beer ballads, gospel tunes, heartbroken confessionals, straight-up honky tonk foot-stompers), but his road songs stand apart as some of his most distinctive, most ambitious, and most quintessentially “Roger-esque” material. Taken together, they comprise a rare constant in an otherwise unpredictable repertoire, a long-time obsession that spanned his entire career—from his 1959 cover of Charlie Ryan’s fast-talking hit “Hot Rod Lincoln” to his antic homage to the Burma Shaving Cream Company’s iconic highway ad campaign, “Burma Shave”; from his self-described “experimental” tune “Hitch-hiker,” a spoken-song tribute to his early traveling troubadour days, to “I’ve Been a Long Time Leaving,” a song Garrison Keillor once singled out for having the only lyric in the history of English poetry to have “ever depicted well the backwash of the wind from a semi going by on the highway.” Add to that Miller’s cover (the first-ever) of Kristofferson’s road classic “Me and Bobby McGee” and his own soulful ode to wanderlust, “River in the Rain,” from Big River, the Broadway musical that won him a Tony Award in 1985. One thing is clear: whatever the era, when we look back at Miller’s life and music, a road runs through it.5

From “The Binging Bellhop” to the King of the Road Inn

Born in 1936 in Fort Worth, Texas and raised on a farm just across the Oklahoma border, Miller left home at age 17 to join the Army (“My education was Korea, Clash of ’52,” he said) and ended up playing in The Circle ‘A’ Wranglers, a hillbilly service band founded by country great Faron Young. A self-described “fiddle player turned writer, turned singer, turned comedian,” Miller paid his dues on the road early on, touring the southern Corn Pone and Kerosene Circuit as a fiddler for Minnie Pearl and a drummer for Young. First known as “The Singing Bellhop,” a name he acquired as an elevator operator at Nashville’s Andrew Jackson Hotel, Miller made his home throughout much of the 1950s and early ’60s in the South’s music capital, where his legendary feats of epic immoderation quickly earned him a reputation as the “Wild Child” of Music Row. Whether Miller should properly be considered “southern” is debatable (his family tree has roots in Arkansas, Kentucky, Texas, and Tennessee), but his impact on country music is beyond dispute. (He referred to his own particular kind of country music as being for “the whole country.”) Miller, who in his countrypolitan prime tended to favor mod ties and smoking jackets over the western boots and hats of his country contemporaries (Marty Stuart called him the “cardigan sweater guy on the edge of town”), may not have always looked the part of a Nashville star, but the town embraced him and remained his musical home even after he moved away. “When I got there,” Kristofferson recalled, “[Roger Miller] was the guy everyone wanted to be.” By the early 1970s, the former bellhop, who frequently jet-setted from Holly-wood to Nashville to record, drop in on friends, or just pick up a bag of his favorite Krystal hamburgers, even had a hotel named for him. With its rooftop lounge and accompanying penthouse suite (complete with a swinging double bed), Miller’s King of the Road Inn was, for a time, the unofficial center of Nashville’s thriving music scene.6

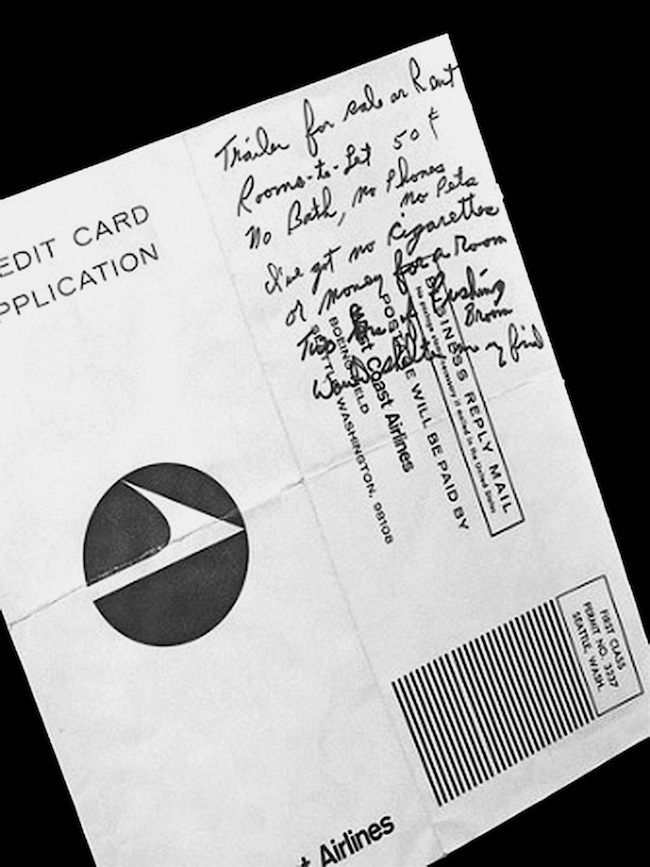

But success had not come easily or nearly fast enough for the young man with the roving disposition. After two frustrated attempts at launching a solo career, first with Starday Records in Texas (where he wrote and recorded with future country greats George Jones and Johnny Paycheck) and later with Chet Atkins at RCA in Nashville, Miller hatched a plan to take the advance he earned from recording his first (and what he assumed would be his last) album, “Roger and Out,” to fund a move to Hollywood where he hoped to study acting—that is, before “Dang Me” became a surprise number-one smash in 1964. Suddenly the singer who just weeks before had been lucky to draw even a few stragglers at a nightclub (“Had four people in the audience and got a hot check,” Miller recalled) was back on the road again, which is where he came across those now-famous words he later scribbled down along with a few others on a folded-over West Coast Airlines credit card application:

Trailer for Sale or Rent

Rooms-to-Let 50¢

No Bath, no Phones no Pets

I’ve got no cigarettes

Or Money for a room

Two hours of pushing broom

Would shelter me may find7

Though Miller preferred to work fast (he claimed to have written “Dang Me” in four minutes flat), he took his time with this one, writing and revising it over a period of two to four to six weeks (depending on who’s telling the story), the title reportedly coming after a heated exchange with promoter Shelly Snyder, who had taken offense after Miller asked him to make him an appointment at a sauna. “Who the hell do you think you are?” Synder shot back, “The King of the road?” When it finally all came together weeks later in a hotel room in Boise, Idaho, where Miller had brought along a statuette of a hobo to help “induce labor,” the result—a taut, sophisticated mix of found poetry and “drifter’s lingo”—was unlike anything he had done before:

Trailer for sale or rent, rooms to let fifty cents

No phone, no pool, no pets, I ain’t got no cigarettes

Ah, but two hours of pushing broom buys an eight by twelve four-bit room

I’m a man of means by no means, king of the road8

“Song-Singer”

Never fond of self analysis—he feared it would disturb his creative “free fall”—Miller often likened his approach to songwriting to a cat having kittens, “something you went off under the porch and did yourself.” But judging from Miller’s own description of his method, he appears to have been more of what Willie Nelson has called a “song-singer,” that is, someone who “sang songs in progress over and over until it came out right.” As Miller himself once explained, “I’ll take the first line and I’ll sing it, like running up to a wall, and just before I hit that wall the second line will come to me, by forcing myself to sing it. Eventually I find I’ve gotten the wall to move enough to show me the whole song.”9

Miller often likened his approach to songwriting to a cat having kittens, ‘something you went off under the porch and did yourself.’

Just as important to his method was making sure that everything “hooked up,” by which he meant that the lines not only rhymed, but that everything else did, too—vowel sounds, consonants, syllables, the sorts of things English majors go to school to study but which Miller picked up listening to Hank Williams records. As an example, Miller cited Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee,” noting how the first line, “Busted flat in Baton Rouge,” with its series of hard B s and Ts, hooks up nicely and rhythmically with the third line, “Feelin’ nearly faded as my jeans.” “I love the ‘as’ that picks up ‘flat’ and ‘bat,’” said Miller. His contemporary, Harlan Howard, likewise noted an invisible thread of fifteen R sounds running through Hank Williams’s “Cold, Cold Heart”—from the triple Rs in the first line, “I try so hard my dear,” to the “terminal ‘heart’” at the end of the first verse. “Once these words are put together this way,” said Howard, “they don’t come apart.”10

Perhaps it was a similar succession of sounds—“Trailer for Sale or Rent,” with five Rs in that one line alone—that caught Miller’s ear that night on the way to Chicago. Looking back over Miller’s first draft, it appears that he was trying to match this bit of found poetry with lines remembered from other signs (“Rooms-to-let 50¢,” “No Bath, No Pool, No Pets”) that he might have come across on the road. By the final draft, he’d polished the third line (“No bath” became “No phone,” neatly turning the first “no” back on itself) and fixed the fourth line by un-fixing it, replacing the proper “I’ve got” with the more in character “I ain’t got,” which also connects with the other T sounds (trailer, rent, let, fifty, and so on). Then there is that succession of alliterative B s (but, broom, buys, by, bit) and that sly lyrical switchback— “I’m a man of means by no means”— which he matches with another—“every lock that ain’t locked”—before the song is through. Miller may have preferred to work quickly, but he clearly did his homework here. As “hooked up” songs go, this one is about as tight as it gets.11

Of course, what works on the page doesn’t necessarily work on the stage or in the studio. What makes “King” work—Bob Moore’s ambling bass, Pig Robbins’s bluesy piano fills, those famous finger snaps contributed by Miller and publisher Buddy Killen—is the delivery, that syncopated snap that allowed Miller to wring the most out of every syllable of every word. The trick was that kick, that slightly disarming little hitch that set everything just off the beat but right in the groove. Sung this way, “every handout in every town” became “ev-er-y hand-out in ev-er-y town.” Not a word or beat was wasted. This swinging approach may have been an odd choice for a song about a hobo, but then so was Miller’s approach to “Dang Me,” which turned a character who sounds like one sorry son of a gun (“out all night and runnin’ wild / woman sitting home with a month-old child”) into the life of the party. In Miller’s hands, the traditional tear-in-my-beer ballad became a riotously-riffing talking blues. Likewise, with “King” Miller managed to reinvigorate the hobo ballad as he slipped on that “old worn out suit and shoes” and made it swing.

Not that this sort of character was new to country music. Indeed, in some respects, Miller’s hobo was just a cousin to that fellow in the old slouch hat in Pete Graves’s 1953 classic “Just a-Bummin’ Around”—the drifter with a “million friends” who’s “as free as the breeze” and says, “I’ll do as I please.” But Miller took it a step further, recasting his hobo as a well-connected man about town, who knows “every engineer on every train / and all of their children and all of their names.” He’s a connoisseur with humble but discriminating tastes (“I smoke old stogies I have found,” he says, “short but not too big around”), whose cosmopolitan swagger and worldly élan place him more in the company of charming Tin Pan Alley ne’er-do-wells like the hobo mayor in Lorenz Hart’s “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum!” (“The road is your estate,” wrote Hart, “The earth your little dinner plate”) than any of Woody Guthrie’s earnest, road-weary pilgrims. More freewheeler (“I don’t pay no union dues”) than freeloader, Miller’s hobo mostly steers clear of the social commentary found in Jimmie Rodger’s “Hobo’s Meditation” and Guthrie’s “Ramblin’ Round.” Guthrie’s rambler lamented that his life on the road had kept him from being a more respectable fellow, but Miller’s man has no such regrets. He may be a “man of means by no means,” but his voice tells us he’s got more than enough—talent, street smarts, endless good humor—to get by. He’s a “king,” not in spite of the road, but because of it. So was Miller. With “King of the Road,” the old road dog had come into his own.12

“I’m Bound to Catch the Next Greyhound”

Following the success of his definitive road song, Miller figuratively returned home in a tune called “This Town.” Though the song never mentions a place by name, it’s not much of a stretch to say that “this town” was partly inspired by Miller’s hometown of Erick, Oklahoma. There wasn’t much to Erick, whose population then hovered around 1,500 (“including rakes and tractors,” said Miller), just one square mile surrounded by corn rows and cotton fields, which is where Miller spent much of his boyhood, picking cotton on the family farm. Home was a complicated subject for Miller, whose father died just a year after he was born. When his mother fell ill and found herself unable to support the family, he and his two brothers were farmed out to various relations, which is how the Texas-born Miller ended up being raised by his aunt and uncle in Erick, a town so small, he said, the “city limits signs [were] back to back.” “Four street lights and one old grocery,” is how he describes it in the song, which isn’t so much about the town as why the singer has decided to leave it.13

If you ever want to get depressed just come to this town,

Nothing to do from dinner to breakfast in this town

Four street lights and one old grocery

I ain’t long to stay here no-sir-ee

I’m bound to catch the next Greyhound leaving this town.14

Miller had scored a hit a few years before with a song called “Home” (Jim Reeves took it to number two on the country charts) that looked back with regret at the place he had left behind:

I’ve been a traveler the most of my life

I never took a home, I never took a wife

Ran away young and decided to roam

But now I’d like to see my mama and my papa back home.15

But “This Town” took a decidedly different approach, leveling one grievance after another at a home the singer seemingly couldn’t get away from fast enough:

I’ve seen towns ain’t no town bad as this town

It don’t take you long to feel low down in this town

Soon the cotton’s gonna open up and I’m gonna pick it

Just long enough to make enough to buy myself a ticket

I’m bound to catch the next Greyhound leaving this town.

What’s missing on the page, of course, is the tone, which is more upbeat than one might expect. Not only does Miller not sound bitter here, he sounds downright jubilant at times— no surprise considering that by the time he recorded this track in 1965 he had already made his way from Erick to Nashville and all the way to L.A. to become the one who got away. Sounding more relieved than resentful, Miller lets fly one lyrical raspberry after another (“One two three four five six seven / This town can go to the other place, I’m going to heaven”) before capping it off with his version of a vocal victory jig— one of those patented Roger Miller scats—as the song draws to a close. What comes through, aside from the obvious joy he got from singing this one, growling and shouting and showing off some of his more distinctive turns of phrase (rhyming “grocery” with “no-sir-ee,” for instance), is not resentment but the resoluteness of a young man determined to make his escape.

Compared with the idyllic “Home,” which looks longingly back to a place that sounds like a hobo’s paradise, where “the river runs gold, the water tastes good, / the winters ain’t cold,” “This Town,” with its litany of small town frustrations (“We got very little sunshine, very little hay in this town / the mail don’t run but every other day in this town”) feels like the real thing—more lived in, more like the truth. Indeed, tucked in between all the comic one-liners (“we don’t reap, we don’t sow in this town / things are so bad that the weeds won’t grow in this town”) are hints of the serious desperation Miller must have felt growing up in a town where opportunities were hard to come by, a situation that only got worse after he left. When the Eisenhower administration embarked on an ambitious highway construction plan in the 1950s, hundreds of small towns like Erick along the famous “Mother Road” were suddenly bypassed by the interstate, leaving community after community high and dry. As Miller sings:

Here I stand on the dusty road leaving this town

Hoping that dog ain’t got a full load leaving this town

The state built new access for travel

They got the pavement and we got the gravel

That’s the reason everything’s dying round here in this town.

Miller made his fortune traveling down that dusty road, but the town he left behind was not so lucky; the same road that had been his freedom became his home-town’s ruin. “Erick wasn’t much of a town,” he recalled years later, “it passed away in its sleep in 1961 . . . the new freeway came by, Interstate 40 killed it.” That Miller felt compelled to document this bit of local history—some might call it a tragedy—in an otherwise comic takedown of a town not unlike his own, suggests the deep ambivalence he must have felt for the place he once called home.16

If “This Town” was a prequel of sorts to “King of the Road,” a reminder of all the sorry circumstances that drove him to a life on the road in the first place, it was hardly Miller’s last word on the subject. Years later, he penned a tune about the disappointment of one who had gotten where he was going only to find it was not everything he thought it would be. That song, “This Here Town,” never appeared on any of his albums and was never even recorded except on a tape made at a benefit concert in 1978 that Miller performed in Erick. As he explained to the home-town crowd that night, “I’ve been living in Los Angeles the last fifteen years . . . and I was sittin’ out there the other night . . . and got to thinkin’ about Erick.” The result was not a feel-good crowd pleaser but a plaintive, heartfelt confessional— an indication that the longing and loneliness that had driven Miller to leave “this town” had never really left him:

This here town is gettin’ to me

I work hard just to survivebut I ain’t ever been so lonesome

Lord it’s eatin’ me aliveLord I wish I was back where I come from

home is where I long to be

and this here town is home to someone

but this here town ain’t home to me.17

Concrete River

Though his hit-making days were largely behind him after the sixties, the 1970s were hardly a “lost” decade for Miller, who went on to write and record several more albums of original songs, including three tunes for the soundtrack to Walt Disney’s Robin Hood. His success in writing for that film may have been one reason a young producer named Rocco Landesman approached him in 1982 about writing the score for a musical adaptation of Mark Twain’s southern classic, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Though Landesman considered him a natural for the job—his “voice blended perfectly with Twain’s,” he recalled— Miller wasn’t so easily convinced. “Not only had he never written a musical,” said Landesman, “he had never seen one.” As Miller himself put it, “Rocco made me an offer I couldn’t understand.” But he rose to the occasion (“I’m self-rising,” said Miller) and the resulting musical, Big River, went on to win seven Tony Awards, including Best Original Score.

The key, according to Miller, was to find a way into the material— “pieces of myself that I could put into it,” a case in point being the ballad “River in the Rain.” “I had never lived on a river, but it’s not hard to close your eyes and imagine sitting on a bank,” he said. “And I would do that and think about a boy growing up on a river and wondering what he would think . . . probably the same things I would think as a boy growing up on a concrete river, which was Highway 66 going west [to] California. I used to see cars on that highway and wonder where they were going and want to go with them.” Miller perfectly captures that boyhood longing to roam in the song’s early verses, sung by Huck Finn as he drifts along the Mississippi with the runaway slave, Jim.19

River in the rain

Sometimes at night you look like a long white train,

Winding your way away somewhere,

River I love you, don’t you care?When you’re on the run

Running someplace just trying to find the sun

Whether the sunshine, whether the rain,

River I love you just the same

To Huck, the river is a kindred spirit, a fellow fugitive “on the run.” But the river means even more to Jim, who knows that the same river that would take him away from his family forever may be the only thing that can bring them together again. As he sings in the bridge:

But sometimes in a time of trouble

When you’re out of hand and your muddy bubbles

Roll across my floor

Take away the things I treasure

Hell there ain’t no way to measure

Why I love you more

Than I did the day before 20

In the original performance, sung in a hearty baritone by Tony winner Ron Richardson, one hears every bit of the desire and desperation Miller put into it. Miller’s own rendition, released as a single in 1985, finds him in equally fine voice, though a bit out of place amid the track’s slick, radio-friendly production. Perhaps the most moving version is the bootleg recording of a solo performance Miller gave six years later at a concert in Alexandria, Virginia, where he introduced the song by recalling his experience growing up along the “concrete river”:

Highway 66 ran through my hometown. I didn’t get to see it except on Saturdays. We’d go into town and I’d see cars going west and wonder where they was going and most of them were headed for California. There are two breeds of Okies. Those who went to California in the thirties and them that couldn’t afford it. My folks stayed. I got to thinkin’ about a boy growin’ up on that river. And he was wondering where it was going probably. So I wrote this.21

Made just a year and a half before his death, this recording, spare as it is, is a revelation. Alone on stage with just his guitar, Miller finds the sweet spot in the song and in himself, between the land-locked Okie he once was— the boy who, like Huck, had “never seen the sea”—and the world-wise, well-traveled troubadour he became.

Roger Miller Boulevard

“I never forget that music has given me the freedom to move around,” said Willie Nelson, and the same could be said of Roger Miller, who learned early on that rambling—whether by boxcar or bus or Rambler station wagon—could free up the music inside oneself, too. In his last years, flush with his success on Broadway, Miller eventually spent less time on the road and settled into home life with his wife, Mary, and their young children. But some things never changed. As Mary recalled, “You could be riding in the car with Roger and he would write a whole song. He’d say, ‘can you write this down?’ and we have all these pieces of paper with songs scribbled on them, things would just come to him like that.” Though Miller’s pace slowed, his mind was restless as ever. Dwight Yoakam likened writing with Miller to “trying to ride a bicycle alongside a taxiing Lear jet.” After his death from cancer in 1992 at the age of 56, Miller was posthumously inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame and later honored with a museum in his home-town along a stretch of Route 66 renamed Roger Miller Boulevard—a fitting tribute to a man who forever remained a soul in motion.22

Brian Carpenter’s articles on the South have appeared in The Southern Review, Southern Literary Journal, The Companion to Southern Literature, and Cornbread Nation: The Best of Southern Food Writing. He recently co-edited the anthology Grit Lit: A Rough South Reader, which was named a Book of the Year by ForeWord Reviews and a Best of the South selection by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.NOTES

- Quote attributed to Roger Miller by Cheryl McCall in Willie Nelson with Bud Shrake, Willie: An Autobiography (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 241.

- Roger Miller in “Audio Interview” with Wink Martindale, Country Legends: Roger Miller, King of the Road CD: (Bci / Eclipse Music, 2004); Bill Anderson in Ain’t Got No Cigarettes: Memories of Music Legend Roger Miller, ed. Lyle E. Style (Winnipeg, MB: Great Plains Publications, 2005), 79; Miller, “Audio Interview,” Country Legends CD; Don Bowman in Ain’t Got No Cigarettes, 43; Miller, “Audio Interview,” Country Legends CD.

- Joe Nick Patoski, Willie Nelson: An Epic Life (New York: Little Brown, 2008), 98; Graeme Thomson, Willie Nelson: The Outlaw (London: Virgin, 2006), 41; Willie: An Autobiography, 138; Otto Kitsinger, liner notes to Roger Miller: King of the Road CD (Bear Family Records, 2004), 9.

- William Whitworth, “Why Don’t We Just Hum for a While,” New Yorker, March 1, 1969, 56; Kitsinger, notes to Roger Miller: King of the Road CD: 11; Mel Tillis quoted in Ain’t Got No Cigarettes, 27–28; William Whitworth, “Why Don’t We Just Hum for a While,” New Yorker, March 1, 1969, 56; Kris Kristofferson quoted in Ain’t Got No Cigarettes, 135; Tillis quoted in Ain’t Got No Cigarettes, 27; Colin Escot, Hank Williams: The Biography, revised ed. (New York: Back Bay Books, 2004), 62–63.

- Kitsinger, notes to Roger Miller: King of the Road CD: 11; Garrison Keillor, quote from the April 13, 1991 broadcast of The American Radio Company of the Air (American Public Media).

- Miller as quoted by Eva Dolin, “Does Roger Miller Know What He Wants?,” Country Song Roundup, February 1965: 28; from File 00309, Roger Miller Clipping File, Frist Library and Archive, Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville, TN; Daniel Cooper, liner notes to King of the Road: The Genius of Roger Miller CD box set (Mercury Nashville, 1995; ASIN: B000001EDZ): 7; Whitworth, New Yorker, 42; Don Cusic, Roger Miller: Dang Him! A Biography (Nashville, TN: Brackish Publishing, 2012), 15–17; Miller as quoted by Donna Ulankowski, “Miller Flows with Musical’s Popularity,” Chicago, IL Calumet (March 14, 1986), Roger Miller Clipping File, Frist Library and Archive, Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville, TN; quotes from Ain’t Got No Cigarettes: Ken Stange, 261; Marty Stuart, 96; Kris Kristofferson, 136; Norro Wilson, 299; David Allan Coe, 264; B. J. Thomas, 277.

- Miller in Whitworth, New Yorker, 59; Early lyrics from “King of the Road” courtesy of the Roger Miller Museum, Erick, Oklahoma.

- Cooper, King of the Road liner notes: 19; Mel Tillis, quoted in Ain’t Got No Cigarettes, 28–29; Miller, quoted in Cooper, King of the Road liner notes, 19; “The Unhokey Okie,” Time Magazine, March 19, 1965.

- Miller in the New Yorker, 62; Miller quoted by Dwight Yoakam, Ain’t Got No Cigarettes, 297; Nelson quoted by Dave Hickey, “The Song in Country Music,” A New Literary History of America (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2009), 845; Miller quoted on Nashville Songwriters Foundation website, accessed September 24, 2012, http://www.nashvillesongwritersfoundation.com/l-o/roger-miller.aspx.

- Miller quoted by Hickey, A New Literary History of America, 845; Harlan Howard quoted by Hickey, New Literary History, 845–46.

- Miller put this lyrical turn-around to good use in other tunes as well, including “That’s Why I Love You Like I Do” (“In other words, there are no words”) and “Chug-a-Lug” (“we uncovered a covered-up moonshine still”).

- Pete Graves, “Just a-Bummin Around”; Woody Guthrie, “Hobo’s Lullaby.”

- Miller quoted in “Roger Miller,” Country Music: The Encyclopedia, eds. Irwin Stambler and Grelun Landon (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1997), 311.

- “This Town” from the album The Third Time Around (Smash Records/Mercury, 1965).

- “Home” from King of the Road: The Genius of Roger Miller CD box set (Mercury Nashville, 1995; ASIN: B000001EDZ).

- Miller quote from a rare recording posted on the Roger Miller Museum website, http://www.rogermillermuseum.com/rogerkris72.html. Miller’s comments were recorded in 1971 when he joined Kris Kristofferson onstage at a club in Escondido, CA, called “In the Alley.”

- Miller quote from the CD Roger Miller Live, courtesy of the Roger Miller Museum in Erick, Oklahoma.

- Rocco Landesman, “Roger Miller: King of the Rhyme,” New York Times, July 20, 2003; Miller “self-rising” quote from Wayne Bledsoe, “‘Self-Rising’ Roger Miller Expands Boundaries as Broadway Composer,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, May 17, 1990, Roger Miller Clipping File, Frist Library and Archive, Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville, TN.

- Miller quoted in Song: The World’s Best Songwriters on Creating the Music that Moves Us, ed. J. Douglas Waterman (Cincinnati, OH: Writer’s Digest Books, 2007), 228.

- Roger Miller, “River in the Rain” from the soundtrack album Big River: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Original Broadway Cast Recording (MCA, 1985).

- Miller quote from bootleg recording of February 16, 1991 concert in Alexandria, Virginia, http://www.beehivecandy.com/2009/08/roger-miller-live-usa-1991.html.

- Willie Nelson, The Tao of Willie: A Guide to the Happiness in Your Heart (New York: Gotham Books, 2006), 112; David C. MacKenzie, “Roger ‘n Ray,” Tulsa World, Friday, February 6, 1987, Roger Miller Clipping File, Frist Library and Archive, Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville, TN; Mary Miller quoted by Mike Bronco, “King of the Hits: Roger Miller,” Country Music Greats 5.1 (Spring 2003): 26; Dwight Yoakam quoted in Ain’t Got No Cigarettes, 295.