McClellanville, a seaside fishing village, was founded in the early 1850s by rice planters from the Santee Delta. The little village became the summer home of these wealthy planters, who left their plantations for a few months each year to escape illnesses like malaria. The village contained modest “shotgun” houses and some very fine, large homes of grand architectural detail. Several oyster and crab factories were built along Jeremy Creek.

Here, I’ve gathered photographs and my journal entries from 1998 to 2010, as well as the thoughts of my fellow author and colleague William “Billy” Baldwin. This is my humble attempt to capture a vanishing culture in the fishing village of McClellanville, South Carolina.1

The Salt Marsh

In the South Carolina Lowcountry lie alluvial regions and much swampland. The coast is a labyrinth of bays, inlets, and streams draining into the rivers from the mainland. North of Georgetown, a half-moon of unbroken beach extends to the North Carolina boundary, and south of Georgetown, to the Savannah River, two thirds of the coastline is a border of barrier islands with lovely beaches. The salt rivers separating these islands from the mainland furnish a safe inland waterway from Winyah Bay to Savannah. The Intracoastal Waterway runs parallel to the Atlantic Ocean. Some lengths consist of natural inlets, saltwater rivers, bays, and sounds; others are artificial canals. It provides a navigable route along its length without many of the hazards of travel on the open sea.

South Carolina salt marshes are flat, expansive landscapes of green during the summer and brown during the winter. At low tide, creeks sketch zigzagging scenes. As high tide comes, dark waters flow into the paddy. To view this from above is breathtaking, yet the wetland can be more hostile than beautiful. The cane-like marsh grass beats your body. Walking the spongy gray bogs along the massive salt marsh requires caution. The oozing mud clings to your feet and sinks you to the waist.

The abundance of food in the marsh sustains shrimp, crabs, oysters, and fish. These inhabitants must maintain a salt balance. Mud dwellers burrow into the mud at high tide to avoid predators. At low tide, they move over the muddy surface for feeding. The mud is a hazard as well as a haven. Lack of oxygen is a problem at low tide, when the burrows become dry or fill with stagnant water. While most creatures can adapt to slight changes in salinity, the water in the marsh is subject to abrupt changes. During storms, salinity at high tide approaches that of seawater, while after a heavy rain, particularly at low tide, the water of the estuary may be almost fresh. Stationary or sessile animals, such as oysters and clams, are forced to slow their metabolisms to reduce their oxygen needs.

Traditional fishing ways here are as diverse as the coastal waterways. Of the more than 150 species of saltwater fish inhabiting the coastal waters, some twenty are valuable for food, as are economically important invertebrate fauna, including shrimp, oysters, and crabs. According to Billy, McClellanville native Jack Leland has said that, when he was a boy in the 1920s, each Saturday morning Big Creek would be lined with black families in oyster bateaus, gathering their seafood for the week, casting, picking oysters, fishing for croaker and spot. Long Creek, which entered in the edge of the Bay, was called the Psalm because it was the answer to people’s prayers.

Jeremy Creek runs through Cape Romain. Along the creek, a small fishing colony of seafaring folk lived on barges and houseboats when I visited McClellanville in 1999. Trawlers roped in orderly fashion to the dock awaited the next fishing excursion. Packinghouses were erected along Jeremy Creek. Mayor Rutledge Leland still owns a retail seafood market behind one of these packinghouses. “Froggy,” a longtime fisher, owned a houseboat tied to the crab factory pier. He kept tight quarters, with a small kitchen and an old sofa bed placed under the cabin window. A ladder ran from the wooden pier to the deck. On the deck, only clotheslines and his old dog kept him company.2

In the tidal creeks at high tide, shellfish and clam shells were covered by saltwater that flowed from Bulls Bay. At low tide, the flats and sandbars emerged to reveal driftwood, interspersed with waste from the seafood factories. Seagulls dipped and dived into the trash heap to pick at food remains from the shellfish harvest. It was an El Niño year. The weather was not particularly cold for winter, but rainy. Fishermen waited. The sea was too rough to go out. The birds migrated into the creek and seemed to be the first creatures aware of the coming storm.

Fresh or Fried: A Southern Cultures Seafood Reader

Twelve fish(ish) tales from the archives (with accompaniments). Read the whole platter here.

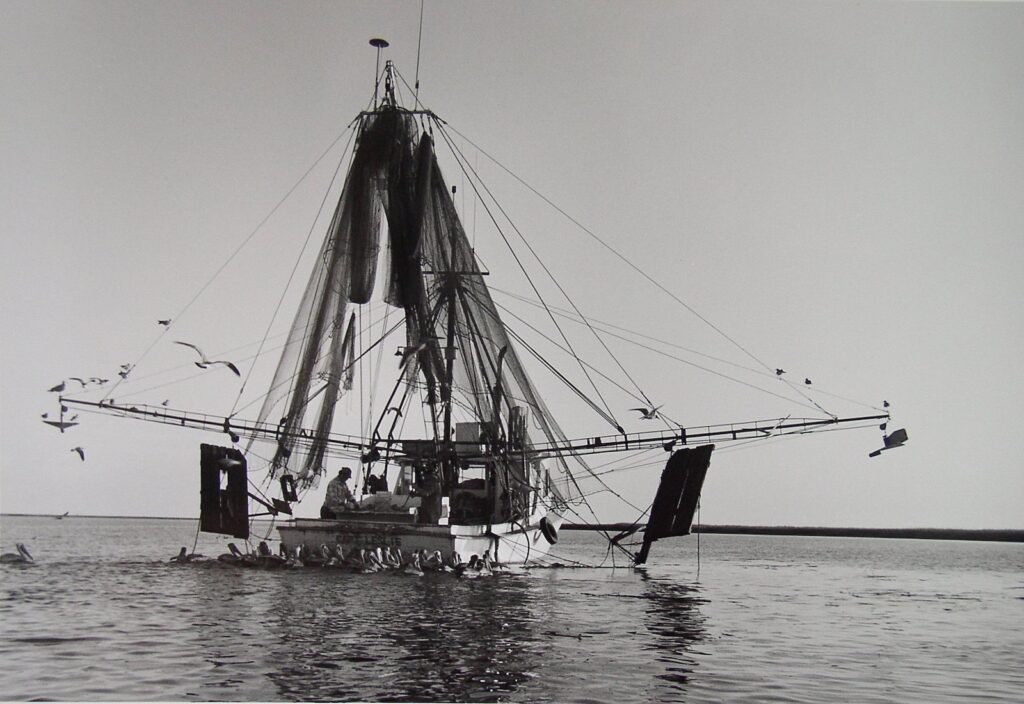

Shrimping

For a brief time in the 1920s and ’30s, a small group of Portuguese fishermen operating trawlers migrated from Florida to South Carolina and began to harvest shrimp in the waters near McClellanville. Prior to their arrival, local fishermen were harvesting shrimp from small wooden boats using cast nets. McClellanville became a self-sufficient community with an economy largely dependent on the sea; fishers harvest among the finest shrimp, fish, and shellfish along the South Carolina coast.

In the summer of 1977, the Archibald Rutledge Academy sponsored the first Lowcountry Shrimp Festival. The event focuses on the blessing of the village’s shrimping fleet, as local shrimp boat captains and crews prepare for the upcoming shrimp season. To this day, trawlers, festooned with colorful flags and pennants, slowly parade down Jeremy Creek to receive the prayers of the local clergy for a safe, bountiful season. Following the blessing, a floral wreath is laid upon the waters as a memorial to those who have been lost at sea.

During the shrimping season, many local people prepared for the canning process at the dock—a large, metal, enclosed shed containing long wooden tables lined with waste bins. There, workers headed shrimp and prepared the catch for shipping. When I was there in 1999, I watched as they snapped the heads off the shrimp and threw them across long tables, earning 20 cents per ten-quart bucket. Today, the shrimp-canning factory on the dock still exists, but the operation has been scaled down.3

Shrimp season in this area runs roughly from mid May to the end of December, with the most productive months being the white shrimp run of September and October. Boats often leave the dock for a week at a time, but just as commonly they go and come every day . . . Before entering the ocean, the outriggers are lowered on each side and once “outside,” the doors and nets are drug into the water, and the forward momentum of the boat causes the doors to sink and spread the net wide. The captain runs the winch and the striker does the rest.

As Billy has described,

We arrived at the dock at about 4 a.m. in early June 1998, one of my first trips. We waited about thirty minutes as several trawlers passed by on their way down the creek. We looked for the one that was to head us to the inlet waterway, Five Fathom Creek. As the trawler approached, it flashed its spotlight on us and quietly eased against the pier.4

Captain Clarence Weston and a striker named James Mazych completed some last-minute work on the nets. The try net is a small net about ten feet wide that swings down from the port side of the boat to test the water for shrimp. It runs along the bottom and is usually left out five or ten minutes. If sufficient shrimp are caught, the big net goes down in the same area. If few are caught, the boat usually moves to another location.

I went up front to watch the horizon, now faintly visible, and other boats heading out to sea on the same mission. The wind was brisk and the water a bit choppy, but the boat was holding a steady course, traveling against the tide at 2.2 knots. It was still too early to do much talking, so I settled down to enjoy the invigorating ocean breeze whipping through the cabin. The shore behind us was barely visible as the early morning skies began to brighten and the lights from various settlements and buoys along the way gave the channel a haunted appearance. Billy recalls,

About 5:15 we passed a red turning light floating along the Intercoastal Waterway and at 5:30 passed by Cape Romain, an uninhabited island that stretches some twenty miles along the Atlantic Coast. Captain Weston began talking with other shrimp boats by means of the radio, while looking at the underwater sonar detector.

A tow lasts about two hours, but small samplings are made with the try net every fifteen minutes or so. Once the nets are hauled back, the bags are swung on board and emptied. Then the striker (the deck hand) is responsible for culling out the shrimp from the trash, washing the shrimp and icing them below deck. This he does while the captain tries to figure out where the shrimp will show up next. After four tows, it’s back inside where the doors and nets are pulled on board, the outriggers are raised, and the boat makes the five-mile trip to the dock.

Captain Weston looked tough-skinned and rugged. He respected the ocean and spent a lifetime mastering its lore. He handled his trawler with ease and caution. He was a patient and accommodating host throughout the day.

The boat, Miss Tonya, was named after his daughter. Powered by a 165-horsepower engine, she had a net weight of thirteen tons and a gross weight of twenty-three tons, and measured fifty-three-feet long and seventeen- and-a-half-feet wide. The captain bought the trawler secondhand and rebuilt it to his standards. Captain and crew usually left the dock at about three or four in the morning in order to be at the mouth of the sound by daybreak. In the winter, they often stayed out for a week, but during the warmer months, when shrimp were harder to keep iced, they went out for only a couple of days at a time.

At about six o’clock, we were well past the sound and Captain Weston ordered the try net let out. Shrimp, like many other swimming species, are not permanent residents of the marsh. They are mobile enough to move in and out of the marsh, and, to the dismay of the commercial shrimper, they often do this unpredictably. They spawn offshore, and, after the eggs hatch, the tiny, immature shrimp depend on ocean currents and tides to push them back up into the marsh. There, they find abundant food and refuge from predators. Shrimp adjust to the abrupt changes in temperature and salinity in the marsh by moving to more suitable environs.

Nearby boats were also checking their try nets and exchanging their results with other boats via their two-way radios. The second haul was only slightly better than the first, so we headed toward the coastal town of Awendaw, where the big net was let out. The big net is funnel-shaped, about sixty-feet wide, and equipped with heavy wooden “shrimp doors” which pull away from each other in the water, keeping the net open. The net typically drags for more than two hours while the boat travels over a fairly wide area in a seemingly random pattern. As we begin to tow, a trail of muddy water marks our path. The sun has finally risen, and I begin to take photographs.

Soon after the big net was let out, the boat began to pull heavy and we settled down to wait. With the net down and speed reduced, Captain Weston took the opportunity to fix breakfast. He cooked the shrimp caught earlier in the try net, along with grits, bacon, sausage, and coffee.

While waiting for Mazych to pull the big net up, I inspected the boat and picked up a bit of information from the striker, making certain to not get in his way. July and August, I was told, were the two slackest months of the season, while May, June, September, October, and November were the best. When the season ended of the South Carolina coast, the boat usually went to Florida for the winter season, as did most of the other independent operators.

After two hours of dragging the big net, we made preparations to pull it in. We covered a lot of territory, but learned from other boat operators that the catch was apt to be light. Just before we pulled the net in, several porpoises broke the water’s surface. They played hide- and-seek behind the net. Captain Weston said this was not uncommon, as porpoises like to eat the small fish that escape through the net.

After about two hours of dragging, Mazych pulled in the net. Captain Weston adjusted the cables and started the big power winches, hauling the heavy net over the side of the boat and onto the deck. With a powerful jerk of the doors, the net lurched out of the water across the bow, leaving several hundred pounds of fish and various other forms of sea life squirming and flopping. The catch included giant spider crabs, catfish, blue crabs, squid, spot fish, whiting, Spanish mackerel, sting rays, crawfish, starfish, and a number of “pin cushions”—curious little fish with prickly horns that swell up like balls when threatened. There were quite a few shrimp, but not enough to make the drag very profitable.

After examining the catch, Captain Weston decided not to make any more drags and to return home. Most of the other boats in the area appeared to be doing the same. Mazych set about sorting and heading the shrimp and separating the other edible fish, washing the “bycatch”—small fish and debris caught unintentionally—overboard with a large hose. We started home toward Jeremy Creek. We returned to the docks and unloaded the shrimp at the factory, where they were weighed and packed for shipment.

Hurricane Hugo

On September 21, 1989, Hurricane Hugo swept through Charleston, South Carolina. The region’s most severe hurricane in thirty-five years, Hugo moved into South Carolina about 11:30 p.m. with 135 mph winds and a five-foot tidal surge that battered a largely evacuated Charleston.5

Torrential rain caused severe flooding, and tornadoes were reported spinning of the walls of the massive hurricane. The wind snapped tall pine trees as it moved toward the center of the state. The tidal surge was thought to reach seventeen feet as it barreled across Bulls Bay, just south of McClellanville.

In 2009, The State—a daily newspaper out of Columbia, South Carolina—published an article on Hugo’s impact. The article features an interview with McClellanville native Forrest Morrison about his family’s experience evacuating to a motel forty miles away:

We got back at 3:30 or 4 the next afternoon. What we saw were two large, 68-foot shrimp trawlers in the driveway. They were stopped by a big live oak tree from coming into the house.

Upstairs, we had put plywood on the front windows, and it looked like you’d gone to dinner and come back. No damage. Downstairs we had 6 feet of salt water (at the height of the storm). There was about 6 inches of pluff mud, shrimp, and crabs coating the whole floor.

We had an antique pine cupboard, primitive pine . . . with the china and crystal my wife had inherited . . . It moved 15 feet, and it was on its back. The water had swollen the door shut. When it dried, we opened it, and there wasn’t a chip. The water just gently raised it up and floated it.6

After the storm, the shrimpers were in a hurry to return to the boatyard to repair or rebuild their shrimp boats. The storm winds and tidal surge had pushed boats into the middle of the village, along with other debris. The hulls were salvageable, but extensive repairs were necessary to put the boats back into service. This loss of time was an unexpected expense and the scarcity of shrimp in local waters caused shrimpers to seek other waters. They headed to New Orleans, and even as far as Galveston, Texas.

Crabbing

Blue crabs occur abundantly in the salt marsh. They swim well enough to avoid or escape severe environmental conditions and hold their own against most marsh predators. The best time of year to harvest them is between October and December.7

I’ve watched as crabbers circle each other in their johnboats, setting crab pots with empty plastic milk bottles attached. They set pots along the creeks that meander through Cape Romain, an average of sixty traps per crabber. The traps are simple square boxes constructed of chicken wire and weighted on the bottom with a rectangle of steel reinforcing rod. A small cylinder projects up from the bottom to hold the bait and entrances for the crabs are cut out of two opposite sides. The traps are positioned so that they stay out of mainstream boat traffic, but remain in deep enough water to stay submerged at low tide. When the wire crab pots sink, crabbers know there are crabs piled inside. Each trap is marked with an empty plastic milk bottle or a Styrofoam buoy, attached with enough line to compensate for the highest spring tide.

Except during the winter months, the fishermen arrive at dawn, when it is a little cooler in the creek. Scores of boats dock at isolated locations deep within the marsh. These days, large-scale corporate operations are gradually forcing independent crabbers out of business.

Billy describes McClellanville crabbers:

Except in the hardest of winters, the crabbers can be found running their pots—anywhere from 50 to 150 in the local Cape Romain marshes. Each of these wire traps has a bait basket in the center to which the crab finds its way through a funnel opening. Once in, he or she feeds and then swims upward into a second chamber and can’t get out.

Usually the crabber pulls his pots every day, dumps the catch into a sorting box, removes the conchs, flounder, and too small crabs, and sets the rest aside in boxes or baskets. The crabbers here were working basket crabs (those sent north to the restaurants) as well as peeler crabs—the crabs about to shed their hard shells and thus become the desirable “soft shells” that end up in deep fryers.

The crab-picking plant often depended on trawl crabs . . . As with shrimping and oystering, the crabbing industry has taken some hard knocks in recent years. This crab factory has since closed down and the site was turned into waterfront residential lots.

On one of my visits, I accompanied the crabbers in their boat. It circled and a crabber hauled the line hand-over-hand until the trap came out of the water and into the boat. He then quickly shook the captured crabs into the culling box, re-baited the crab pot, and dropped it overboard as he reached for the next trap. By midmorning, the first fifty-five-gallon drum was filled with crabs. The crabbers worked independently, navigating their boats and pulling their traps.

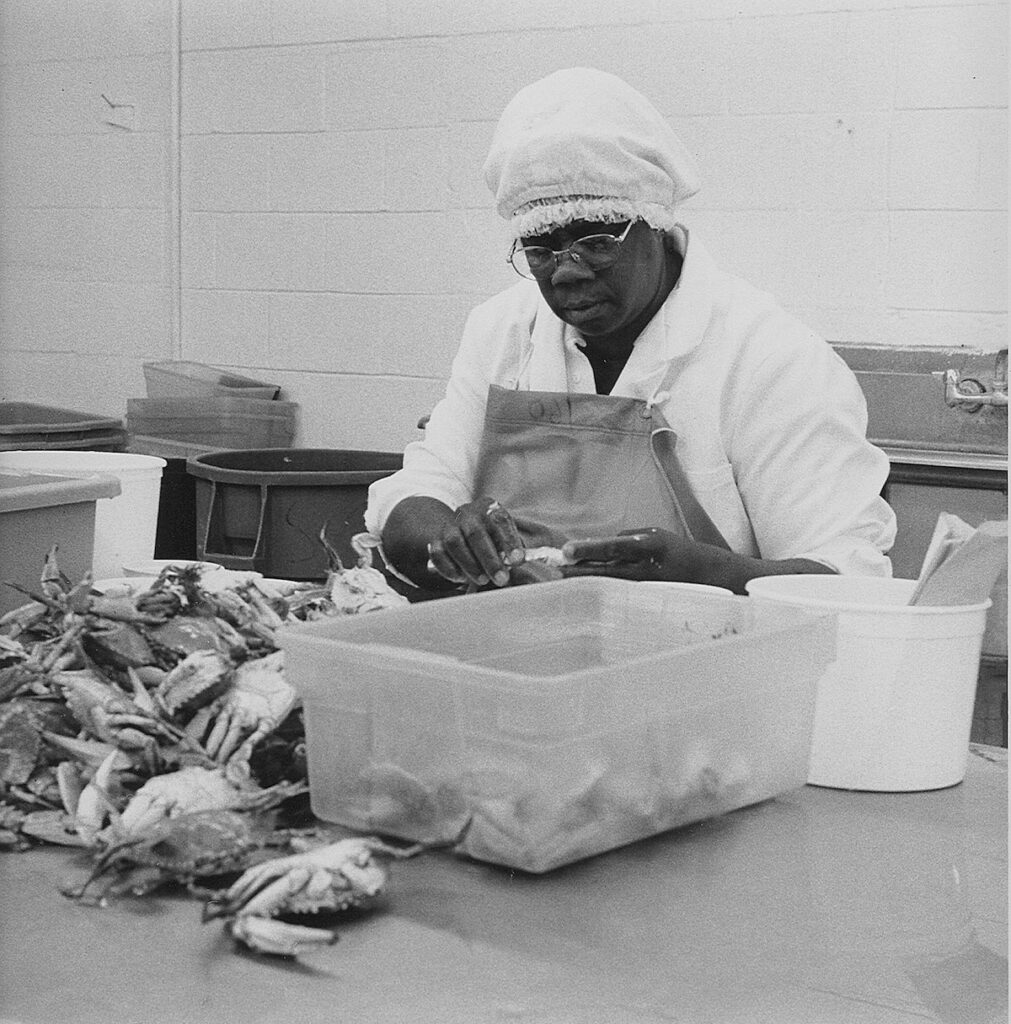

Just after noon, the crabbers met back at the landing. They each had between 300 and 400 pounds of live crabs—a good but not great day. The crabbers hauled their barrels to the edge of Jeremy Creek’s crab factory. A male factory worker cooked the crabs that had been caught that morning in a giant stainless steel pressure cooker and put them into the factory cooler. The next day, factory workers would handpick the crustaceans and can, process, label, and package their meat.

The crab factory was a white concrete building with white walls, in which the women wore white uniforms with matching white hats while they extracted white meat from the breast of the boiled crab. They broke off the crab shells, removed the gills—which we called the “dead man”—then broke the crab at its spine and pulled off its legs and pinching claws. Painstakingly, the women removed the meat from the body and pulled the dark meat from the claws.

The women at the crab company were a hard group to photograph, since they work in a sterile environment. I had to get wrapped in white and wear a hairnet. And the women think of their workplace as private. It took a whole morning for me to convince these women to let me photograph them. I even dressed in a white uniform with a net on my head. I walked out to get a cup of coffee, and Billy rushed after me to tell me they were ready! I hurried back into the workroom. The women weren’t ashamed of working, but they were hesitant to be photographed in work clothes. They are churchwomen and prefer to be seen in church clothes.

Today, the crab factory is gone. It has been replaced by modern luxury mansions, and sportfishing yachts line the creek.

Oystering

Alligator Creek is one of the most productive, natural subtidal areas on Cape Romain. All the necessary conditions are present for oysters to establish themselves and achieve a maximum growth rate. Seed planting is necessary to maintain the future harvest.

The most common type of mollusk in oyster beds is known as the “cluster oyster.” These oysters grow in the intertidal zone and are formed by successive yearly sets on the older oysters. As new sets are made, the cluster grows, sometimes becoming quite large, taking the shape of a small bush. On occasion, such clusters may reach a length of eighteen inches or more. As new growth occurs, the added weight pushes the bottom oysters into the mud, where they eventually suffocate. Only the outer and top-most oysters survive. Some oysterers will break up these clusters into single oysters and redeposit them for future growth. Billy explains:

Oysters are picked in the cool of the year; as the saying goes—those months whose names have an “r” in them. Since the local oyster grounds have been heavily harvested, the oyster crew often tows three hours down an inland waterway to better grounds about fifteen miles to the south.

Once there, the twenty-foot bateaux disperse, usually one man to each, and for the last two hours of the receding tide and the first hour of the flood the pickers work, quickly tossing the oysters from bank to boat. The oysters are culled as they go, the dead shell being knocked aside, but often further culling is done on the return trip. It’s usually late at night before the last boat has been shoveled out at the dock, and the next trip can start even before daylight. It’s hard, hard work, especially on those freezing northeaster days when the tide’s not going to drop but groceries are still to be bought.

Like the shrimping, the oystering industry has had to struggle along over the last several years. Some time back oysters were shucked in McClellanville, but now it’s oyster roasts and the like that serve the catch.

On one of my visits, the towboat pulled the empty boats out of the creek early in the morning. The small boats trailed behind, tied to each other by strong ropes. On the towboat, the oystermen ate breakfast and slept before a long day of harvesting. Once in the tidal marshes, they gathered at the gunwale of the towboat, waiting to jump into their individual boats. The captain yanked the tie-up ropes, and, once untethered, the oystermen went quickly—all in sync. They cranked their outboard motors and headed in different directions across the bay. To keep me safe, they sent me out on the only fiberglass boat; the others were homemade wooden boats.

I saw the other oystermen from a distance. We jumped off our boat into the spongy, gray pluff mud. The young oyster fisher pulled his boat onto the marsh grass. It was low tide. Wearing heavy rubber gloves, he slung the cluster of oysters into the back of the boat. He used a steel rake to break apart the clusters, beating off the dead barnacles. Bending at the waist, he worked continuously in a stooped posture. He took no lunch break and did not pause to wipe the sweat from his brow or remove the mud from his boots. I stepped into the mud with my camera on a tripod and photographed him.

He had to fill the whole boat with oysters while the tide was out. A full load came to about forty bushels. He flung them in and finished up before the tide came in. Heavy with oysters, the boat rested on the bank and we sat, waiting for it to float. Finally, we all made it back to the towboat in the bay. After roping all the heavy boats together, we started our slow tow back to Jeremy Creek. The men gathered in the hull of the boat. They heated their lunch buckets on the kerosene heater. Some ate steamed oysters from the day’s pick.

Returning, 2010

Returning in 2010, I drove along tranquil Pinckney Street, which was almost unchanged. It leads to a public dock on Jeremy Creek. The crab factory is gone. The workers were laid off a year before the factory was demolished to make room for waterfront lots, mansions. Even today, the new houses are few. During the summer months, gnats, horse flies, and mosquitos descend. Plus, communities want to remain small. They resist putting in sewer systems; without sewers, subdivisions cannot be built. But newcomers are arriving, slowly.

Froggy’s houseboat was no longer roped to the pier. The shrimp factory’s steel doors were rolled down and locked. Few trawlers remained along the creek. I interviewed an old fisherman called Smoke, the supervisor on the crab dock, who told me local fishermen were pushed out of the market by producers of cheap, imported seafood from Southeast Asia. The salt marshes have also deteriorated over years of environmental stress. The village lifeline was connected to the harvest of the ocean. The creek people have lived their lives on the water. I felt a chill from the sea breezes still coming off the bay. It is hard to come back to a vanishing culture.

This essay first appeared in the Food: The Coast issue (vol. 24, no. 1: Spring 2018).

Documentary fieldworker Vennie Deas Moore has published several books tracing people and their ties to southern landscapes. Through her photographs, Deas Moore has captured the passing traditions of coastal communities in South Carolina as waterway construction increasingly leads to recreational activities and residential living. She worked for thirty years as a southeastern cross-cultural research consultant, and has served as a historian at the McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina.

NOTES

- Portions of this essay have been drawn from Deas Moore’s book Home: Portraits from the Carolina Coast, and have been updated for publication here. Among Baldwin’s many contributions to southern literature are his bestselling biography Mrs. Whaley and her Charleston Garden; the Lillian Smith Book Award–winning novel The Hard to Catch Mercy; and Gold Benjamin Franklin Award–winning poetry collections, The Unpainted South and These Our Offerings. His writing has appeared in magazines such as Southern Living, Veranda, Southern Accents, Charleston and Garden & Gun.

- Sewee Visitor & Environmental Education Center, Awendaw, SC.

- “An Upcountry Goes Shrimping,” The State Magazine, September 10, 1950.

- I had asked Mayor Rutledge B. Leland III to give me permission to document the seafood traditions over a period of years. Leland, the lifetime mayor of the village, also owns one of the few surviving factory and seafood companies on Jeremy Creek.

- Laura Parker and William Booth, “Hurricane Hugo Rips Through South Carolina,” Washington Post, September 22, 1989, ProQuest.

- Megan Sexton, “Shrimp Boats in the Driveway? Hugo Did It,” The State, August 25, 2009, http://www.thestate.com/news/special-reports/hurricane-hugo/article14345894.html.

- “Get in the Salt,” South Carolina Wildlife, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, updated July/August 2010, http://www.scwildlife.com/articles/julyaug2010/getinthesalt.html.