“As the noted Music City chronicler Peter Cooper put it . . . . ‘Death, taxes, and backlash are inevitable for those fortunate enough to be successful.’ Such was the case with Kristofferson, whose fall paralleled his rise.”

Attendees at the 1970 Country Music Association awards were startled when Roy Clark announced that Kris Kristofferson’s “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” beat out Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee” for Song of the Year. Amid applause and some gasps, a dazed, disheveled, long-haired Kristofferson stumbled up the steps of the Ryman Auditorium, looking an awful lot like the down-and-out character in his award-winning song who “stumbled down the stairs to meet the day.” Some in the audience laughed nervously after the artist delivered a garbled acceptance speech that probably left many wondering what type of coming down awaited him the next morning. Kristofferson later denied being under the influence of any substance, claiming that the shock of the award announcement startled him so much that he reared his head back and banged it against a wooden pew. Physically and emotionally stunned, he stumbled down the aisle and onto the stage. Regardless of what put the singer in that condition, the image resonated. One viewer remembers Tennessee Ernie Ford snarking that he, for one, “liked country music because you could tell the boys from the girls.” Ford and others breathed a sigh of relief when Haggard’s apparent tribute to squares, college deans, and manly footwear earned him album and single of the year honors. Writing in the New York Times, however, Paul Hemphill announced that, like it or not, “Kris Kristofferson is the new Nashville sound.”1

One viewer remembers Tennessee Ernie Ford snarking that he, for one, “liked country music because you could tell the boys from the girls.”

Kristofferson staggered into the spotlight just as country music was hitting the airwaves and igniting the national imagination. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the genre experienced a nationwide surge in popularity, presence, and profits. Record sales soared as more country tunes crossed over onto the pop charts with great success. The number of radio stations playing exclusively country skyrocketed from eighty-one in 1961 to 650 by 1970, with the Northeast capitulating, as one New York Times writer characterized it, “to the sound that has swept most of the rest of the country.” Rolling Stone printed feature-length articles on the music coming out of Nashville and country stars appeared on the covers of Time, Look, and Newsweek. This national ascendancy of what many considered a particularly southern form of musical expression prompted a fair amount of soul-searching as well as some navel-gazing. Numerous singers, songwriters, journalists, music critics, producers, pundits, and historians chimed in, offering their opinions on what this trend revealed about the nation, the region, and the genre.2

Kristofferson factored into these social, political, and cultural developments in familiar and unfamiliar ways. In a time marked by an obsession with the “far-ranging, fast spreading revolt of the little man against the Establishment,” country music’s focus on the lives of average, everyday men and women drew a great deal of attention. Jefferson Cowie describes the genre as “embattled terrain in the class wars of the 1970s,” with many listeners tuning in in hopes of gauging the cultural and political pulse of white working- and middle-class Americans. Music scholars and journalists alike have held that country music fomented or at least exemplified societal divisions, and Haggard’s “Okie” and “The Fightin’ Side of Me,” seen as “ballads of the silent majority,” solidified this reputation.3

A look at Kristofferson’s rise to stardom reveals that, at a moment when Americans were deeply divided, many looked to him and his Nashville peers as artists who might bridge these divides. His appeal highlights a central but often overlooked component of country music’s attraction. In a search for what they considered real, honest lives and experiences, many Americans of varied regional, economic, and ideological backgrounds latched onto country music’s apparent authenticity—a tortured and malleable concept in its own right—as an antidote to materialism, estrangement, and polarization. Kristofferson and country music promised their listeners—young and old, liberal and conservative—a “politics of recognition and status” that ran counter to that being offered by the likes of George Wallace and Richard Nixon. For Kristofferson, this appeal proved potent but short-lived. The highs and lows of his early career revealed that, amid a lot of chatter about newness, country music remained tethered to certain preconceptions limiting the power and possibilities of its appeal.4

Chet Atkins and other Nashville music makers had devoted much of the 1950s and 1960s to making their product, in the words of historian Bill C. Malone, “more ‘respectable’ and therefore, they reasoned, more marketable.” Conceding the youth market to rockabilly and rock ’n’ roll, they courted white, middle-class listeners with what Jeffrey J. Lange has characterized as the smooth, mellow, “lighthearted and sentimental pieces” that came to be known as the Nashville Sound and country pop. Orchestral arrangements, horn sections, and “muted guitars” supplanted fiddles and pedal steel on tunes that journalist Chet Flippo described as “carefully formulated, inoffensive music designed to appeal to fans of pop music while still retaining enough of a country identity to make it on jukeboxes in the honky-tonks.”5

Although Nashville singers, songwriters, and executives thrilled at their rapidly growing audience, some critics worried that such success came at the expense of “that intimacy, that authenticity” that faded when “the music goes uptown.” Some feared that the art and artists would succumb to the forces of “prosperity and television” already homogenizing the nation and the South. Several raised the timeless concern that country music had yet again sold out, sacrificing cold, hard realism for slickness, gimmickry, and popular acclaim. At the same time, many fans also equated popularity with respectability, seeing the success of their favorite artists as a “validation of their own tastes.”6

Such concerns were part of larger fears about the South itself. As the 1960s set, another New South rose, a “domesticated, commercialized” Sunbelt that historian Bruce J. Schulman characterized as “more moon shot than moonshine, more entrepreneurial than agricultural.” Schulman likened the country music of this era to the self-conscious “reddening” of America whereby social climbing “demi-rednecks”—good ol’ suburban accountants and middle managers—railed against government intervention and blared country tunes out the windows of the shiny new pickups they drove to the country club or strip mall. Charles L. Hughes claims that performers and industry executives gladly went along for the ride, pushing this “conservative connection” in their ongoing quest for commercial success and cultural relevance.7

As some gnashed their teeth at what all this success meant for the genre and region, a report from the Southern Growth Policies Board viewed it as an opportunity to welcome a “prodigal region” back “to the national family.” Time magazine informed readers that this latest iteration of Dixie “whistle[d] a different tune,” accompanied by “new images, new goals” that promoted the region economically, culturally, and politically as a land of hardworking, law-abiding, plain-speaking, God-fearing, patriotic, salt-of-the-earth white folk. This image sold well in a country grappling with signs of its declining international stature, a slowing economy, persistent societal unrest, and a distinct lack of faith in its traditional political leaders. Indeed, a cynical, jaded, and worried nation began looking to the South for models of decency, prosperity, guidance, order, and honesty. Time magazine reimagined and recast the stereotypical redneck as a down-home southerner who possessed an “innate wisdom, an instinct about people and an unwavering loyalty that makes him the one friend you would turn to.” Such hopes required rose-colored glasses that bordered on opaque, but it reflected what historian James C. Cobb identified as “a snowballing tendency to forgive, forget, and even applaud the South’s peculiarities.”8

Time magazine reimagined and recast the stereotypical redneck as a down-home southerner who possessed an “innate wisdom, an instinct about people and an unwavering loyalty that makes him the one friend you would turn to.”

These conversations fed into larger, even more contentious debates over the state of American culture and politics. Some embraced and others regretted what writer John Egerton labelled the “Southernization of America” and the “Americanization of Dixie.” Several pundits attributed an increasingly polarized and hostile national sociopolitical environment to the former, while others lamented the bland homogenization and phony commercialization that accompanied the latter. Where Egerton detected strains of the Americanization of the South in the music coming out of Nashville, some listeners heard the southernization of America, most notably as a cultural extension of President Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” to attract white, working-class voters. In “Red Necks, White Sox, and Blue Ribbon Fear,” Florence King described contemporary country music as “hymns to the fear of change that is dividing America along strict political, social, and sexual lines, and encouraging all working people to emulate and identify with the very worst sort of Southern reactionaries.” Richard Goldstein detected something sinister and threatening in a music that “comes equipped with a very specific set of values . . . [including] political conservatism, strongly differentiated male and female roles, a heavily punitive morality, racism.” Another writer described country music as “simplistic, bigoted, emotional, maudlin, jingoistic, provincial, and dominated by male chauvinism,” adding that those “characteristics accurately reflect the concerns and attitudes of roughly one-fourth the population of the United States.”9

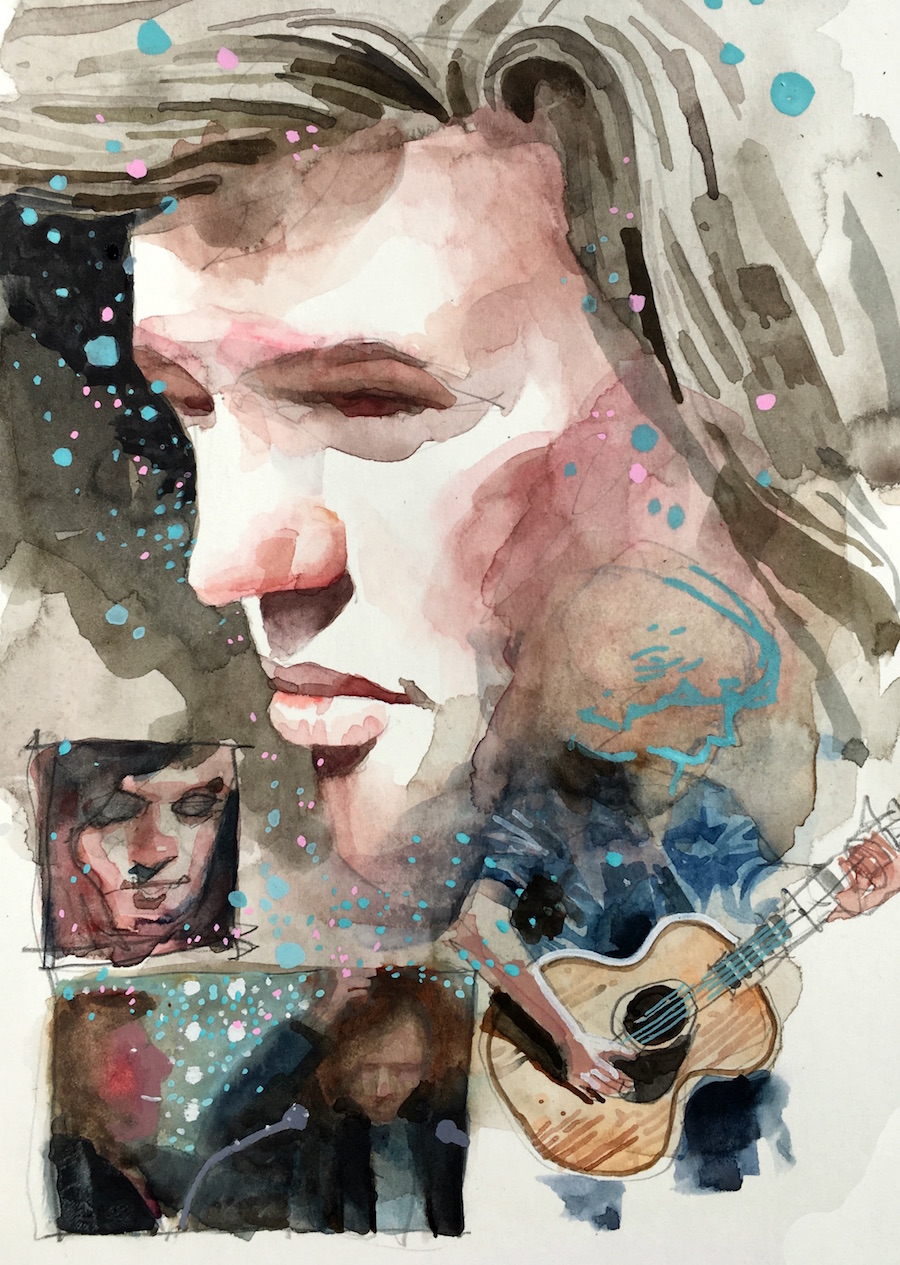

Some, like Frye Gaillard, dug a bit deeper, uncovering a strain of “folk-protest” in country music dating back to its Appalachian roots. In Watermelon Wine, he focused on “a rebellious class of musicians . . . a feisty, sometimes temperamental bunch, who write with poetic fervor about nearly every aspect of the human condition.” Kristofferson was one of these artists, emerging as the face, voice, and “spiritual leader” of what was heralded as a “new breed” of Nashville singer-songwriter who expanded country music’s audience, message, and image in ways much different than Haggard and Atkins.10

Kristofferson, Tom T. Hall, John Hartford, and Mickey Newbury formed the core of a group who came to Music City, USA, in the mid-1960s and over the next several years achieved varying degrees of commercial and critical success. Fans were drawn to their musicianship and lyricism as well as their humanistic, broad-minded, far-ranging commentary on war, drugs, civil rights, poverty, and social alienation. A banjo and fiddle virtuoso, Hartford attracted a great deal of attention through the surreal frankness of his songs. Ralph Emery called him “the most imaginative of the new writers and entertainers to arrive in Music City.” Hall hewed “closest to the traditional country sound,” with straightforward lyrics and melodies containing and, in some cases, masking trenchant social commentaries. His songs tackled issues such as societal racism, intolerance, hatred, and hypocrisy. Newbury composed eclectic melodies, accompanying them with lyrics inspired in part by the Beats, which he sang, according to one listener, “with a voice that is mellow and strong and throbbing with emotion.” Observers commented on the collective intelligence, sophistication, complexity, subtlety, and poetry of the new breed’s work. In some cases, an undercurrent of condescension can be detected, as if the writers were shocked that “hillbilly” music could attract such literate, thoughtful, and urbane artists. Whisperin’ Bill Anderson countered such beliefs, noting that, by dealing with love, despair, regret, and “the hopes and longings of average people” as well as “their frailties and failed dreams,” members of the new breed were doing what country music had always done—they just seemed to be doing it better.11

Fans were drawn to their musicianship and lyricism as well as their humanistic, broad-minded, far-ranging commentary on war, drugs, civil rights, poverty, and social alienation.

Kristofferson intrigued many with his background as a golden gloves boxer, Rhodes Scholar, award-winning short story author, Army Ranger and captain, helicopter pilot, and erstwhile English professor who gave all that up to sweep floors, tend bar, and try to make a living writing songs in a place his parents mocked as “Hicktown, USA.” Critics praised him for bringing depth, sensuousness, and contemporary sensibilities to a genre often derided as basic, simple, and derivative. His work belied popular notions found in various print outlets depicting country as a “reactionary, Wallace-for-President traditionally repressed cultural form” that served, at best, as the “embodiment of middle-class propriety and respect for law and order” and, at worst, as the music of “red-necked Neanderthals” with “primitive notions of democracy.” Bill Malone credits Kristofferson in particular with reinvigorating country music in the “intimate” way he paired traditional country themes of love, lonesomeness, and heartache with “individual soul-searching and passionate quests for identity and self-fulfillment.”12

In 1969, Pete Hamill published an extensive piece called “The Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class” in which he enumerated perceived grievances held by a vast number of Americans, including boredom, lack of respect or recognition, social alienation, hypocrisy, and “the debasement of the American dream.” Country music struck a chord with these aggrieved men and women as it addressed their concerns in a variety of ways. Some songs and singers lashed out at protestors, welfare recipients, and elites. Others, like Kristofferson, encouraged introspection, empathy, and compassion. Kristofferson did not offer nostalgia or backlash but rather honest, sympathetic accounts of the everyday struggles and concerns of ordinary Americans. He saw materialism, selfishness, and judgmental attitudes as the source of individual and societal anxieties. He provided few tangible solutions, but even his most fatalistic songs acknowledged and legitimized the public and private struggles many Americans faced.13

Kristofferson championed freedom, self-expression, intimacy, and tolerance in a way that brought “a gentle intensity to his portraits of frustration, defeat and lost romance.” His eponymous debut album contained such classics as “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” and “Me and Bobby McGee.” In between those tunes, he introduced recurring themes in his work, singing about the importance of artists staying true to their callings and the dangers of sacrificing personal connections for material gain. Another hit, “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” rendered a mournful but touching depiction of a one-night stand that offered the narrator a respite from his longing, sadness, and loneliness. Some country artists found the song too overtly sexual or even immoral. This worry was no doubt compounded when Sammi Smith cut a version that topped the country charts, challenging a double standard that depicted such liaisons as a largely male prerogative. Kristofferson crossed another line with his original version of “The Best of All Possible Worlds,” in which the song’s character asks his arresting officer, “Why I never saw a man locked in that jail of yours who wasn’t either black or poor as me?” According to Charles Hughes, this proved a bit much for a genre whose “most common critiques involved class, regional identity, and patriotism, but . . . tended to eschew overt statements when it came to race.” As such, record executives required Kristofferson to replace “black or poor as me” with “low down poor as me.” Even so, it did not go unnoticed that Kristofferson’s lyrical musings on the “elusive concept of ‘freedom’” echoed other voices that “resounded through sixties struggles for national liberation, feminism, and civil rights.”14

Kristofferson wrote about the poor, the homeless, the abused, the neglected, and the marginalized in a way that asked his audience to avoid condemnation and instead empathize with their plight. A Rolling Stone review of Kristofferson’s second album, The Silver Tongued Devil and I, announced that “country music is developing a sense of the complexities of moral issues, and Kris Kristofferson writes about the new world.” The reviewer singled out Kristofferson’s recording of “Good Christian Soldier” as a welcome contrast to “the frequent country paean to patriotism.” The song tells the story of “the son of an Okie preacher” kneeling to pray in Vietnam. The narrator explains that any hopes he had of building a “new and better day” had been crushed by watching fellow soldiers break down and spend their time “turning on and learning how to die.” Writing songs that told of junkies and other down-and-outers taking “a beating in a world they meant no harm,” Kristofferson introduced new, contemporary characters while invoking a longstanding country music tradition pioneered by artists such as Jimmie Rodgers, who immortalized Depression-era drifters, transients, and other forgotten members of society. While Flippo took such songs as evidence of Kristofferson’s “bag of heretical tricks” in which he “carried rock’s revolutionary message in a country idiom,” others noted that country music had a long history of approaching contemporary troubles—substance abuse, sexual infidelity, despair, regret, and “grappling with the human and imperfect condition”—in a compassionate manner.15

In “Jesus Was a Capricorn,” Kristofferson reproached “eggheads,” “rednecks,” and “hippies” for their lack of empathy and understanding toward one another. He regretted that “everybody’s gotta have somebody to look down on / Who they can feel better than at any time they please / Someone doin’ something dirty that decent folk can frown on.” Noting that the song’s title character “ate organic food . . . believed in love and peace / And never wore no shoes” and sported “long hair, beard, and sandals and a funky bunch of friends,” he reckoned that, in the political climate of 1972, “they’d just nail him up / If he come down again.” In “The Law is for Protection of the People,” he condemned the heavy-handed use of force to protect “decent folks like you and me” from drunks like Billy Dalton and hippies like Homer Lee Honeycutt, who were simply “walking through this world without a care.”16

Such works defied country music’s supposedly monolithic embrace of conservatism. Indeed, the works of Kristofferson, Tom T. Hall, and others suggested that “being country doesn’t necessarily mean one votes for George Wallace and thinks Strom Thurmond is a great American.” Rather than treating the “country music craze” as indicative of the nation’s political divides, many believed the music could bridge some of these gaps. Writers for the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Newsweek, and the Los Angeles Times welcomed the arrival of “free-thinking, modern songwriters” like the new breed, who retained a traditional focus on the “feelings of average people in everyday situations” but whose talent, originality, energy, and social commentary attracted a broad range of listeners who could “identify now more than ever with the heroes and heroines of a song; real people struggling with the real problems of jobs and homes and survival in a complicated world.” One review described Kristofferson as “a new minstrel capable of carrying the poetry of plain folk to the sophisticated masses.” Songwriter Harlan Howard predicted that country music could reveal that “the silent majority might agree with a lot of things the not so silent majority says.” Hall took some satisfaction in revealing that many Americans shared the same “private frustrations and fears.” Viewing country as a “music of reconciliation,” Rolling Stone’s Jann S. Wenner joined others like Frye Gaillard who hoped the music’s rise presaged a “national depolarization” built upon the understanding and respect engendered by these artists and their work.17

One review described Kristofferson as “a new minstrel capable of carrying the poetry of plain folk to the sophisticated masses.”

Kristofferson’s appearance, persona, and presumed proclivities drew as much attention as his music. While Austin, Texas, was establishing itself as a beachhead of progressive country during this time, Music City retained its reputation as the staid and conservative home of traditional country. Earlier forays into Nashville by the likes of the Byrds and Bob Dylan alternatingly inspired, frustrated, and angered music fans, who regarded them as rock star dalliances with their country cousins. The notion held that progressive country came from either outsiders coming into Nashville or insiders who had escaped Music City. Neither scenario challenged the widely held belief voiced by author Ben Fong-Torres that the country music of Nashville “represented the straight world . . . even if it was being played by dope smokers.” While some could and did treat Dylan’s Nashville Skyline and the Byrds’s Sweetheart of the Rodeo as the work of “put-ons,” Kristofferson was a bona fide country music performer, one who had paid his dues in Music City and would proudly tell anyone that did not like Hank Williams to kiss his ass. Even with these credentials, Kristofferson’s talent, message, and demeanor sent people scrambling for new ways to describe and categorize him.18

In 1970, a writer for The Tennessean announced, “If there was a particular way the Great Nashville Songwriter is supposed to look . . . Kris Kristofferson would not look like it.” Another commentator found Kristofferson more suited for a commune than the Grand Ole Opry. Some evaluated Kristofferson’s work in relation to that of his peers and predecessors, but others went a bit far afield, comparing him to F. Scott Fitzgerald and describing him as Odysseus in Levi’s and a country Heathcliff from Wuthering Heights. Even though Kristofferson objected to Hemphill’s claims that he “openly smokes pot” (he replied that he didn’t “even closedly smoke marijuana”), many critics wondered how “traditionalists” would take to “long haired, bearded, and rough talking” performers singing about getting stoned and writing “bluntly sensual protest songs that are sometimes only a shade away from being underground.” The answer soon became clear: they may not like it but, as long as it sold, they went along with it. Kristofferson released a string of top-ten albums and wrote a slew of award-winning songs that would go on to become number-one hits for Johnny Cash, Ray Price, Sammi Smith, and Jerry Lee Lewis. Country music historian Tony Scherman claims that, in the wake of Janis Joplin’s recording of “Me and Bobby McGee,” Kristofferson “became the hottest songwriter in Nashville, an anti-authoritarian smack dab in the belly of the establishment.” Sure enough, country music commentator Dave Hickey observed that after “Kristofferson scandalized [Music City] by showing up at a black tie banquet in blue jeans—the next year, everyone looks like extras in a rodeo movie. That’s free enterprise Nashville.”19

Kristofferson blazed a path to respectability and commercial success that did not go through the adult middle class and that challenged rather than appealed to certain fears and prejudices. Hemphill attributed Kristofferson’s academic credentials, non-conformist attitude, and particular interest in sex and freedom to his popularity with “the campus and to intellectual sets.” Young people enjoyed his answer song to Haggard’s “Okie,” where he joked that people in Muskogee dropped their BVDS instead of acid and got drunk “like God wants us to do” rather than smoke that “deadly marijuana.” They appreciated his refusal to judge people by their appearance and welcomed his indictments of “Mr. Marvin Middle Class,” who hypocritically blamed youthful unrest on the sinful example set by the Rolling Stones. A writer for the New York Times predicted that, given Kristofferson’s varied and accomplished pre-Nashville resume, “he could become a hero to these hordes of kids trying to find their own truths.” The author found this especially true for those “bright middle-class kids with the game plan already worked out for them, suddenly deciding they don’t want the ball, breaking out of the mold their parents have made.”20

Young people saw and heard themselves in Kristofferson. He echoed concerns expressed by student activists in their Port Huron Statement about societal apathy, vowing to continue singing “to the people who don’t listen” even if that meant “I’ll die explaining how the things that they complain about are things they could be changing, hoping someone’s gonna care.” He depicted himself and some of his peers as “walking contradictions,” a term Abbie Hoffman applied to Yippies in Revolution for the Hell of It.21

Although some considered country music and the counterculture to be diametrically opposed, at the height of Kristofferson’s popularity, reviewers credited the artist with “reaching a plateau in music no other singer has managed,” gaining full acceptance among the “followers of country music and the aficionados of rock.” With a song comparing a certain “riddle speaking prophet” to hippies; and the smash hit “Me and Bobby McGee”—which Michael J. Kramer deems a “countercultural anthem”— Kristofferson seemed to be an artist who could bring together fans of Tennessee Ernie Ford with “hard-rock freaks” on urban campuses. Underground publications had already sussed out parallels between the two, noting, “Substitute dope for booze, and country and rock are talking the same language.” One reporter singled out Kristofferson’s reference to getting “stoned” in “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” as a “classic piece of imagery . . . written by the prototype of the complete rock-country artist.” Harry Haun viewed Kristofferson as a “natural link” between country music and the counterculture. A writer for the underground publication Harry hoped that such music could lead to “communication between freaks and hardhats,” which might “be more to the social good than trying to convince steelworkers through rhetoric that their interests are being destroyed by war and oppression.”22

A writer for the Los Angeles Times labelled Kristofferson a “romantic” rather than a political spokesperson for the times, distinguishing between the two in ways that many at the time did not. Writing in 1960, Arthur Schlesinger identified an “inchoate and elusive” political mood marked by “new forces, new energies, new values” that left people yearning for “individual dignity, identity, and fulfillment in an affluent mass society.” In A Nation of Outsiders, historian Grace Hale tracks a post–World War II obsession with and yearning for authentic experiences among the white middle class that drove some into the New Left, the Economic Research and Action Project, and the Civil Rights Movement, and others into the New Right, the Young Americans for Freedom, and evangelicalism. These quests were animated by a “romance of the outsider,” a conviction that people on the margins of society “possess cultural resources” rooted in hard-earned, honest, real experiences that the protections and comforts of modernity had denied other Americans. According to Hale, young people in particular saw “romanticizing ‘the folk’” as a “form of rebellion against mid-century middle-class values and what people then called mass culture.” They grounded what Doug Rossinow dubbed this “politics of authenticity” in a humanistic worldview that privileged raw, shared emotion and a devotion to honest, free self-expression. In their minds, remaining true to such beliefs no matter the social or material cost offered the most effective means of counteracting the conformity, materialism, apathy, and alienation that was corroding American society. To these young men and women, “artists, outcasts, and the poor” embodied the honesty and “emotional authenticity” at the heart of their personal politics.23

Young people in particular saw “romanticizing ‘the folk’” as a “form of rebellion against mid-century middle-class values and what people then called mass culture.”

Kristofferson and country music seemed especially attuned to this trend with their focus on “human-interest drama, gritty realism, and evocation of values that seemed imperiled by modernity.” When singing about the “materially impoverished and the socially scorned,” performers benefitted from an appearance of honesty and, even more importantly, authenticity. In July 1971, Look magazine placed Kristofferson on the cover of a special issue devoted almost entirely to the country music phenomenon. The lead article attributed the appeal of Kristofferson and other country stars to their “personal credibility with their fans.” When asked about country music’s national popularity, Mickey Newbury replied, “It’s not that Nashville is setting any trends. It’s just that the rest of the world is looking for honesty in everything.” A writer for the Saturday Review remarked, “There’s something about country music that encourages such honesty, such one-syllable eloquence.” Peter Doggett declared, “Country’s very appeal was its authenticity” with performers who seemingly “lived out the everyday dreams and nightmares of their audience.”24

Scholars have long grappled with the concept of authenticity as it relates to the appeal and meaning of country music. Lange and others point out that while the “inherent subjectivity” of the ideal has enabled the genre to adapt to the numerous demographic, geographic, economic, and political changes experienced by its audience, it has also united and divided people when it comes to identifying “real” country music. Lange also agrees that country music’s authenticity “centers on the connection listeners feel towards performers,” with Richard A. Peterson boiling it down to two main components: believability and originality. Peterson and others stress that the former does not depend so much on actuality as it does on credibility “in current context.” Indeed, performers at various times established their authentic bona fides by playing a role, whether it be a country bumpkin, a cowboy or cowgirl, an urbane crooner, or a honky-tonk angel. In each instance, though, they projected an image that fans at the time found familiar, intriguing, and believable. Leigh Edwards agrees that “the country genre makes insistent claims for authenticity, demanding of its performers some proof of credibility.” Such proof represents a mix of style and substance, with some seeking evidence of lived experience, a demonstrable appreciation of and commitment to the music and, in the opinion of author John Grissim, “a voice that oozes sincerity and emotion.” With singers themselves admitting that that no one could or would even want to live out all they sang about in their songs, these attributes give performers an aura of believability that can sustain “fantasies of authenticity.”25

Kristofferson embraced his role as a tried-and-true country poet and picker in word, song, and deed. When asked, he claimed time and again that he was drawn to country music because he found it more honest, emotional, and real than other genres. He wrote about the physical and abstract importance of “naked emotion.” He spoke of freedom as something worth fighting for and preserving, but also as “just another word for nothin’ left to lose.” He cited William Blake as an inspiration and hero, repeatedly quoting the Romantic’s warning that eternal misery and regret awaited any artist who repressed their talents in exchange for material success. In “To Beat the Devil,” he admitted that even though “failure had [him] locked out / On the wrong side of the door,” he “was born a lonely singer” who would continue to “feed the hunger in my soul” and even though he might die broke, he wouldn’t “ever die ashamed.”26

Jack Hurst characterized Kristofferson’s work as “that of an educated and intelligent wanderer, an inveterate prowler into late evenings and deep bottles” who offered unvarnished insights into the plight of the downtrodden with sympathy and sincerity. Embracing Kristofferson as the “balladeer of the dispossessed, the troubadour of losing and losers,” and the “poet laureate of the alienated,” fans and reviewers found his lyrics “always totally believable,” viewing him as a “road weary” singer-songwriter who penned “autobiographical ballads” in the “raw, honest” language of someone who had “lived 100 years hard.” Kristofferson, who was actually in his thirties at the time, summed up his own views on creative authenticity, asserting that “writing anything honest or artistic has to come out of something you experience,” and adding, “You don’t necessarily have to follow the steps, but you have to at least feel the emotion that is called up by the experience.”27

Kristofferson’s reputation as a seeming “walking contradiction”—a left-leaning soldier, an Oxford-educated janitor, a country and western intellectual—worked in his favor, lending him credibility with those who latched on to whatever part of his persona they most identified with. Hippies adopted the long-haired, bearded Kristofferson as one of their own. Longtime country music fans roared along as he sang about all the “drinks that I ain’t drunk.” His plaintive growl of a singing voice helped him connect with any listener looking for a straightforward exposition of their own private hardships and struggles. His audiences could understand and appreciate it when he growled “screw you buddy” at hecklers.28

As the noted Music City chronicler Peter Cooper put it, however, “Death, taxes, and backlash are inevitable for those fortunate enough to be successful.” Such was the case with Kristofferson, whose fall paralleled his rise. Flippo pitied Kristofferson when he saw the tide turning against him, regretting that commentators and fans had “expected, even demanded” that Kristofferson “save country music from its cotton candy vapidity and be the new—or at least the interim— Bob Dylan.” When he failed to fulfill each and every expected role, no matter how “absurd,” Kristofferson received “an unequal share of abuse.” Even positive reviews of Kristofferson’s performances mixed praise with skepticism as some wondered why this intellectual golden child would stoop to the level of shit kickers who idolized Hank Williams.29

Finding it increasingly difficult to grasp the fact that someone like Kristofferson could find a receptive audience within country music, critics turned on the artist in the most biting way they could: by questioning his authenticity. When he moved to California and started acting in movies, more and more fans and critics began wondering if he had been playing a role all along. Rex Reed pointed out that the “Kristofferson portrayal of a hell-raising ‘good ole country boy’ has appeal for the unwashed masses and if he can act on screen half as well as he does off screen, success seems guaranteed.” In a review of Kristofferson’s third album, Patrick Carr wondered, “Is he striking a pose which he knows will get him by?” Carr claimed, “Kristofferson has slowly grown closer to dealing in a stereotype of himself, and [this album] demonstrates that the stereotype has almost taken over.” Rolling Stone’s Ben Gerson went even further, lashing out at “the crippling dullness of a man who has expended all his energy contriving an image.” Mocking Kristofferson’s reputation as “a cracker barrel philosopher, able to spout truisms from a life rooted in unadorned reality,” he called him a put-on, a “country and western Jim Morrison” who is “no more a good old boy from Nashville than Neil Young is a rancher, George Harrison a mystic, or Frank Zappa a freak.”30

Gerson concluded that Kristofferson’s commercial success “condemns” him as an inauthentic artist. Kristofferson acknowledged that, early on in their careers, he and his peers “thought ‘commercial’ was a dirty word,” adding later that “it wasn’t a very fair appraisal of the situation because nobody was recording our stuff.” Once success came, however, they saw no “conflict between art and commercialism,” claiming that financial success freed them up to be even more creative and honest in their work. Scholars who have also examined the link between country music commercialism and perceived authenticity by and large endorse Chet Atkins’s claim that “nothing sells like the truth.”31

As Kristofferson’s authenticity came into question, his record sales suffered. By the mid-1970s, Kristofferson and the new breed had given way to “Willie and Waylon and the Boys” as the progressive, popular face and sound of country music. This was accompanied by the continued influence of country pop with John Denver and Olivia Newton-John crossing over into the fold. Kristofferson has been linked to both these trends. Tony Scherman claims that his anti-establishment ethos and success “lit a fuse that hissed and popped with Waylon Jennings’s brooding early-seventies country-rock and finally exploded into the utterly improbable superstardom of Willie Nelson.” Another writer identified Denver and Newton-John as “Mr. Kristofferson’s musical kin—albeit some distant,” tracing their lineage to 1970 when he staggered onto the Ryman stage with a message and image that would make “country mod.” While such claims are compelling, a few have observed that, unlike much of Kristofferson’s work, songs about “country roads,” “honky-tonk heroes,” and “getting back to the basics of love” offered up nostalgia and good times without “any sort of ideological commitment” or even acknowledgement of societal injustice or suffering.32

Kristofferson’s going up and coming down confirms that country music during this time was political, but not necessarily in the way people tend to assume. Even as a bona fide superstar, he occupied a tenuous place in the current context of a music that had and would accommodate middle-class sensibilities and outlaw rowdiness, but would find a Rhodes Scholar singing hillbilly tunes, a progressive voice within a supposedly conservative genre both fascinating and confounding. An inability to reconcile the message with these contemporary expectations of the medium contributed to Kristofferson’s decline and helped sustain what one observer called “the glib generalization” that country music rose to popularity during this time on a surge of right-wing sentiment. This diminishes the faith that some people had in country music’s ability to overcome rather than perpetuate cultural and political divisions. Country music of the 1960s and 1970s tapped into a broad-based desire for authenticity, one that included but extended well beyond political conservatism. Kristofferson’s songs about freedom, struggle, alienation, truth, despair, and an aching for pure emotional connections cut across cultural, ideological, regional, and generational lines. Country music’s longstanding reputation for authenticity amplified his message, carrying it far and wide. Kristofferson was not a paradox or an anomaly; he was a part of country music traditions. As a writer for Look magazine asserted in 1971, the genre can accommodate the style and politics of “Kris Kristofferson alongside Roy Acuff, as long as country music does not surrender its authenticity.” For this belief to endure, fans and critics alike would have had to relinquish traditional assumptions about country music, broadening their impressions and expectations of the genre, its performers, and its audience and accept more inclusive notions of what the music is, who it speaks for, and what it has to say.33

This essay appeared in the Inside/Outside Issue (vol. 25, no. 2: Summer 2019).

Alex Macaulay is an associate professor of history and graduate program director at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, North Carolina. His favorite Kristofferson album is The Silver Tongued Devil and I, but he likes them all.NOTES

- biggestkkfan, “Kris Kristofferson – CMA award 1970,” Youtube video, 00:50, August 12, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-VOCJYFe93A; “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down,” track 12 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson, Legacy/Monument Records, 1970, re-released as Me and Bobby McGee, Monument Records, 1971; Roxy Gordon, “Partly Truth and Partly Fiction: A Pilgrim’s Perspective on Kris Kristofferson,” No Depression: The Journal of Roots Music, October 31, 1999, 86; Kristofferson, “Kris Kristofferson Just Wanted ‘Respect for Country Music,’” interview by Chet Flippo, CMT, November 8, 2004, http://www.cmt.com/news/1493550/kris-kristofferson-just-wanted-respect-for-country-music/; and Paul Hemphill, “Kris Kristofferson is the New Nashville Sound,” New York Times, December 6, 1970, https://www.nytimes.com/1970/12/06/archives/kris-kristofferson-is-the-new-nashville-sound-the-new-nashville.html.

- John Buckley, “Country Music and American Values,” Popular Music and Society 6, no. 4 (1979): 293; Paul Dimaggio, Richard A. Peterson, and Jack Esco Jr., “Country Music: Ballad of the Silent Majority,” in The Sounds of Social Change: Studies in Popular Culture, eds. R. Serge Denisoff and Richard A. Peterson (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1972), 39; McCandlish Phillips, “Leaders in Country Music See Chance to Win the City,” New York Times, April 16, 1973, https://www.nytimes.com/1973/04/16/archives/leaders-in-country-music-see-chance-to-win-the-city-countrymusic.html; Jerry Hopkins, “The Hollywood Hillbillies: What’s Old is New,” Rolling Stone, March 1, 1969, 1, 4; Paul Hemphill, The Nashville Sound: Bright Lights and Country Music (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1970), 30–40, 57, 177–179; “Why Country Music is Suddenly Big Business,” US News and World Report, July 29, 1974, 58–60; “Lord, They’ve Done It All,” Time, May 6, 1974, 51–55; Cory Lock, “Countercultural Cowboys: Progressive Texas Country of the 1970s and 1980s,” Journal of Texas Music History 3, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 15–16; John Grissim, Country Music: White Man’s Blues (New York: Paperback Library, 1970), 10; and Bill C. Malone, Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 244.

- Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: New Press, 2010), 2, 10, 170, 174; Grissim, Blues, 10–11; Bill C. Malone and David Stricklin, Southern Music/American Music, rev. ed. (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003), 132; James C. Cobb, “From Muskogee to Luckenbach: Country Music and the ‘Southernization’ of America,” in Redefining Southern Culture: Mind and Identity in the Modern South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999), 78–79; R. Serge Denisoff, “Kent State, Muskogee and the White House,” Broadside, no. 108, July/August 1970, 2–4; Jonathan D. McCarthy, Richard A. Peterson, and William L. Yancey, “Singing Along With the Silent Majority,” in Side-Saddle on the Golden Calf: Social Structure and Popular Culture in America, ed. George H. Lewis (Pacific Palisades, CA: Goodyear, 1972), 287–314; Dimaggio, Peterson, and Esco, “Ballad,” 44– 45; Charles L. Hughes, Country Soul: Making Music and Race in the American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 1; Hemphill, Nashville Sound, 153; and Malone, Raisin’, ix, 133, 238–240.

- Cowie, Stayin’ Alive, 134.

- Jeffrey J. Lange, Smile When You Call Me a Hillbilly: Country Music’s Struggle for Respectability, 1939–1954 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004), 4, 196, 199, 201; Malone and Stricklin, Southern Music, 129–130, 132–135; Bill C. Malone and Jocelyn R. Neal, Country Music, U.S.A., 3rd ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 254–267; and Chet Flippo, “From the Bump-Bump Room to the Barricades: Waylon, Tompall, Glaser and the Outlaw Revolution,” in Country: The Music and the Musicians: From the Beginnings to the ’90s, eds. Paul Kingsbury and Alan Axelrod (New York: Abbeville, 1988), 455.

- Hemphill, Nashville Sound, 241; Grissim, Blues, 58, 199–200, 298–299; Frye Gaillard, Watermelon Wine: The Spirit of Country Music (New York: St. Martin’s, 1978), xv, 28, 172, 176; Lange, Hillbilly, 4; John Egerton, The Americanization of Dixie: The Southernization of America (New York: Harper’s Magazine Press, 1974), 205–206; Larry L. King, “The Grand Ole Opry,” Harper’s, July 1, 1968, 43–50; “Big Business,” US News and World Report, 60; Charles Portis, “That New Sound From Nashville,” Saturday Evening Post, February 12, 1966, 34; Jerry Hopkins, “Joe South: ‘Country and Western Music is Shit,” Rolling Stone, June 14, 1969, 8; and Diane Pecknold, That Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 168–175, 199.

- Bruce J. Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo, 2002), 103, 105, 106, 117; Cowie, Stayin’ Alive, 170, 174; and Hughes, Country Soul, 129, 132.

- Schulman,Seventies, xiv, 103 (Southern Growth Policies Board quote found here), 114–116, 117; “New Day A’ Coming in the South,” Time, May 31, 1971, 14; Hugh Sidey, “A Visit to Good-Ole-Boys Country,” Time, May 6, 1974, 14; “Those Good Ole Boys,” Time, September 27, 1976, 47; Patrick Carr, “Will the Circle Be Unbroken: The Changing Image of Country Music,” Music and the Musicians, 512–514; Chet Flippo, “Country and Western: Some New-Fangled Ideas,” American Libraries 5, no. 4 (April 1974): 185; Dominic Sandbrook, Mad as Hell: The Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right (New York: Anchor Books, 2012), 135–137; Rick Perlstein, The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014), 581–586; and Cobb, “Muskogee,” 82–84.

- Egerton, Americanization, xix–xxi; Malone, Raisin’, 210, 237–238, 240–241; Cobb, “Muskogee,” 78–79; Schulman, Seventies, 108; Cowie, Stayin’ Alive, 168, 169; Lock, “Countercultural Cowboys,” 16; Hughes, Country Soul, 128, 129, 132; Robert Christgau, “Obvious Believers,” Village Voice, May 1969; Denisoff, “Kent State”; Patrick Anderson, “The Real Nashville,” New York Times, August 31, 1975; Phillips, “Leaders”; Hemphill, “New Nashville”; Kevin Phillips, “Revolutionary Music,” Washington Post, May 6, 1971; Paul Dickson, “Singing to Silent America,” The Nation, February 23, 1970, 211–213; Florence King, “Red Necks, White Socks, and Blue Ribbon Fear: The Nashville Sound of Discontent,” Harper’s, July 1, 1974, 31; Richard Goldstein, “My Country Music Problem . . . and Yours,” Mademoiselle 77, no. 2 (1973): 114–115; Hemphill, Nashville Sound, 116; and Flippo, “New-Fangled,” 185.

- Malone and Neal,Country Music, U.S.A., 304–306; Hemphill, Nashville Sound, 67; Gaillard, Watermelon, 19, 42–46, 52–53 73–74, 183; Hemphill, “New Nashville”; Richard Hilburn, “New Breed Making Musical Impact,” Los Angeles Times, February 15, 1969; Edwin Miller, “Kris Kristofferson: Lonely Sound from Nashville,” Seventeen, April 1971, 131, 200–201; Christopher Wren, “Country Music,” Look, July 13, 1971, 11; Grissim, Blues, 228; Jan Clemens, “Hippies Swarming All Over the Country Music Scene,” Chicago Today, December 11, 1971; Jack Lloyd, “Something New in the Country,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 8, 1971; Robert Hilburn article, October 1970, Kris Kristofferson file, Country Music Hall of Fame, Frist Library and Archive, Nashville (hereafter CMHF); Peter Doggett, Are You Ready for the Country (New York: Penguin Books, 2001), 314–15; Michael Pousner, “Rock N’ Roll: For the Moment At Least Acid’s Draining From Rock,” Tribune Review (Greensburg, PA), August 27, 1971; and Robert Shelton, “When Flat and Scruggs Sing Dylan, What’s Up?,” New York Times, November 24, 1968.

- Andrew Vaughan,John Hartford: Pilot of a Steam Powered Aereo-Plain (Franklin, TN: Stuffworks, 2013); undated flier for John Hartford Looks at Life, John Hartford file, CMHF, Frist Library and Archive, Nashville; Hilburn, “New Breed”; Burt Korall, “A New Breed of Country Musicians Steps Forward,” New York Times, May 21, 1972; Robert Shelton, “It’s So Healthy in the Country,” New York Times, March 24, 1968; Phillips, “Leaders”; Jack Bernhardt, “‘Like Paris in the Twenties’: Notes on a Nashville Scene, 1971–1974,” Journal of Country Music 13, no. 3 (1990): 26–27; Bruce Cook, “‘Tom T. Just Goes His Own Way’: His Country Music is Best Described as Art,” National Observer, January 29, 1972; Grissim, Blues, 13, 60, 224–225, 233; Hemphill, Nashville Sound, 71, 225, 239; Richard Cromelin, review of In Search of a Song, by Tom. T. Hall, Rolling Stone, January 6, 1972, 70; Les Bridges, “Kristofferson: A Legend in His Own Whacked Out Time,” Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1973; Lynn Van Marie, “Mickey’s Music: Memories With a Southern Ring,” Chicago Tribune, March 25, 1973; Clemens, “Hippies Swarming”; “Big Business,” US News and World Report, 59; Malone and Neal, Country Music, U.S.A., 304–306; Cobb, “Muskogee,” 87; Gaillard, Watermelon, 76, 185; and Malone, Raisin’, 13.

- Marshall Chapman, They Came to Nashville (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2010), 3–27; Larry Arnett, “Stranger Than Fiction: The Real Life Adventures of Songwriter Kris Kristofferson,” Country Song Roundup, April 1969, 17–18; Hemphill, “New Nashville”; Grissim, Blues, 224–225, 226–228; David Rensin, “King Kristofferson,” Country Music 2, no. 13 (September 1974): 24–32; Sally Quinn, “Kristofferson: Hits and Myths,” Washington Post, May 18, 1971; Korall, “New Breed”; Doggett, Ready, 311; Alec Dubro, review of The Silver Tongued Devil and I, by Kris Kristofferson, Rolling Stone, September 16, 1971, 42; Townsend Miller, “Who is Kristofferson? Fans Know,” Austin American-Statesman, March 8, 1972; Stereo Review, January 1972, Kristofferson file, CMHF, Frist Library and Archive, Nashville; Bruce Cook, “Nashville’s Counter-Culture,” Saturday Review, October 4, 1975, 48–49; Tom Smucker, “Bob Dylan Meets the Revolution,” Fusion, October 31, 1969, in Bob Dylan: A Retrospective, ed. Craig McGregor (New York: William Morrow, 1972), 299; Malone and Stricklin, Southern Music, 134, 138–139; and Malone and Neal, Country Music U.S.A., 305–306.

- Pete Hamill, “The Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class,” New York Magazine, April 14, 1969; Cowie, Stayin’ Alive, 42; Hemphill, Nashville Sound, 177–179; Malone and Neal, Country Music, U.S.A., 306; and “Just the Other Side of Nowhere,” track 8 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson.

- Malone and Neal, Country Music, U.S.A., 307; Doggett, Ready, 312–314; Joel Vance, “Kris Kristofferson,” in The Best of the Music Makers, ed. George T. Simon (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1979), 328; Kristofferson; “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” by Kris Kristofferson and Fred Foster, track 5 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson; Sammi Smith, vocalist, “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” by Kris Kristofferson and Fred Foster, track 7 on Smith, Help Me Make It Through the Night, Mega, 1970; Hughes, Country Soul, 131; “Best of All Possible Worlds,” track 4 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson; and Peter Cooper, “‘Freedom’s Still the Most Thing for Me’: A Conversation with Kris Kristofferson,” No Depression 55, January–February 2005.

- Dubro, Rolling Stone, September 16, 1971; “Good Christian Soldier,” by Bobby Bare and Billy Joe Shaver, track 4 on Kristofferson, The Silver Tongued Devil and I, Monument Records, 1971; “Billy Dee” and “The Pilgrim, Chapter 33,” tracks 3 and 9 on Kristofferson, The Silver Tongued Devil and I; “Epitaph (Black and Blue),” by Kris Kristofferson and Donnie Fritts, track 10 on Kristofferson, The Silver Tongued Devil and I; “Casey’s Last Ride,” track 7 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson; Malone and Stricklin, Southern Music, 134; Will the Circle Be Unbroken: Country Music in America, eds. Paul Kingsbury and Al-anna Nash (London: DK Publishing, 2006), 278; Malone, Raisin’, 248; Susan Jetton, “Kris’s Country Comes on Strong,” Charlotte Observer, October 16, 1971; and Gaillard, Watermelon, 122, 127, 187.

- “Jesus Was a Capricorn (Owed to John Prine),” track 1 on Kristofferson, Jesus Was A Capricorn, Monument Records, 1972; “The Law is For Protection of the People,” track 6 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson; and “Kris Kristofferson, Nashville’s Best Educated Superstar,” in Showcase: An Entertainment Preview of Music City U.S.A., microfiche, “Kristofferson, Kris,” clipping 1972–1973, CMHF, Frist Library and Archive, Nashville.

- Grissim, Blues, 215; Jann S. Wenner, “Country Tradition Goes to Heart of Dylan Songs,” Rolling Stone, May 25, 1968, 1, 14; Cromelin, Rolling Stone, January 6, 1972; Pete Axthelm, “Lookin’ at Country with Loretta Lynn,” Newsweek, June 18 1973, 65–72; Ray LaRocque, “Kris Kristofferson is a New Hank Williams,” Worcester Telegram, October 24, 1971; Wren, “Country Music,” 13; Dick Richmond, “Kris: I’m No Swaggering Lover,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 4, 1972; and Gaillard, Watermelon, 53.

- Travis Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks: The Countercultural Sounds of Austin’s Progressive Country Music Scene (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 9, 22; Ben Fong-Torres, Hickory Wind: The Life and Times of Gram Parsons (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1991), 97; Malone, Raisin’, 140; Wenner, “Country Tradition,” 14; Hemphill, “New Nashville”; Clemens, “Hippies Swarming”; “If You Don’t Like Hank Williams,” track 10 on Kristofferson, Surreal Thing, One Way Records, 1976; Dubro, Rolling Stone, September 16, 1971.

- Jack Hurst, “Kristofferson Beats the Devil,” Tennessean, September 6, 1970; Jamie Ryburn, “So What?!,” Tulsa Daily World, October 31, 1971; Miller, “Fans Know”; Lloyd, “Something New”; Jetton, “Kris’s Country”; Stereo Review, January 1972; Jack Hurst, “There’s Good Times and Bad Times: Kristofferson Winces Under Image,” Tennessean, January 11, 1971; Quinn, “Hits and Myths”; David Morrison, “Shut Up and Sing,” Atlanta Constitution, November 15, 1974; Hemphill, “New Nashville”; Korall, “New Breed”; Patrick Thomas, “Ex-GI Folkie Kris Kristofferson,” Rolling Stone, March 18, 1971, 20; Ray Rezos, review of Kristofferson, by Kris Kristofferson, Rolling Stone, November 12, 1970, 38; Dubro, Rolling Stone, September 16, 1971; Bill Preston, Jr., “Kristofferson ‘Songwriter of the Year,’” Tennessean, January 20, 1971; Robert Hilburn, “Kristofferson Fuels Country Revival,” Los Angeles Times, February 14, 1971; Robert Hilburn, “Kris Kristofferson at the Troubadour,” Los Angeles Times, June 10, 1971; Jack Garner, “Ex-Rhodes Scholar Country Music Man,” Times-Union (Rochester, NY), October 23, 1971; Malone and Neal, Country Music, U.S.A., 305; Doggett, Ready, 311, 315; 1972 Showcase, CMHF; Tony Scherman, “Country,” American Heritage 45, no. 7 (November 1994); and Rensin, “King Kristofferson,” 30.

- Malone and Stricklin, Southern Music, 132, 138; Grissim, Blues, 248, 297; Cobb, “Muskogee,” 85–86; “Interview with Billy Sherrill,” Journal of Country Music 3, no. 2 (May 1978): 63; Gaillard, Watermelon, 75, 81; Doggett, Ready, 309–310, 311–312; Hurst, “Beats the Devil”; Wren, “Country Music,” 11; William Hedgepeth, “Superstars, Poets, Pickers, Prophets,” Look, July 13, 1971, 30, 35; Malone, Raisin’, 138–139; Times-Union (Albany, NY), September, 8, 1971; Jetton, “Kris’s Country”; Kris Kristofferson, vocalist, “Okie From Muskogee,” by Merle Haggard, recorded December 2, 1972, track 13 on Live At the Philharmonic, Monument Records, 1992; “Blame It on the Stones,” by Kris Kristofferson and Bucky Wilkens, track 1 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson; Pousner, “Acid’s”; Anthony Mancini, “Kris Kristofferson: Good Ole Country Boy for Good Old Country Girls,” Cosmopolitan, September 1972, 178–180; and Hemphill, “New Nashville.”

- “The Port Huron Statement,” The Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/PortHuronStatement, accessed March 19, 2019; “To Beat the Devil,” track 2 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson; Kristofferson, “The Pilgrim- Chapter 33”; Abbie Hoffman, Revolution for the Hell of It (New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 2005), 80.

- Bill Malone, Singing Cowboys and Musical Mountaineers: Southern Culture and the Roots of Country Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003), 112; Cowie, Stayin’ Alive, 169, 178; Carr, “Circle,” 518; Doggett, Ready, 312–313; Mancini, “Good Ole,” 178–180; Michael J. Kramer, The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 27; Ira Allen, “We Don’t Take Our Trips on LSD,” Harry, January 8, 1971, 14, 17; undated article in Fusion, Tom T. Hall file, CMHF, Frist Library and Archive, Nashville; Harry Haun, “‘Easy Rider’ Takes a Wrong Turn on the Freeway,” undated, Kristofferson file, CMHF, Frist Library and Archive, Nashville; “A Great Future Behind Me,” Wyoming Tribune Eagle, December 26, 1971; Ryburn, “So What”; Hemphill, “New Nashville”; and Richmond, “Swaggering Lover.”

- Hilburn, “Troubador”; Arthur Schlesinger, “The New Mood in Politics,” Esquire, June 1960, 58, 60; Doug Rossinow, The Politics of Authenticity: Liberalism, Christianity, and the New Left in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); and Grace Hale, A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love With Rebellion in Postwar America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 1, 3–6, 18, 35, 84, 86, 98, 106, 164, 166, 168, 173, 178–179, 188.

- Malone, Raisin’, ix; Nadine Hubbs, Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 107; Cook, “Goes His Own Way”; Axthelm, “Lookin’,” 67; Portis, “New Sound,” 34; Wren, “Country Music,” 12; Judy Kinnard, “Nashville Sound Spreads to the Village’s Bitter End,” Tennessean, May 3, 1970; “Lord, They’ve Done It All,” 51; Cook, “Counter-Culture,” 48–49; and Doggett, Ready, 308.

- Pousner, “Acid’s”; Leigh Edwards, Johnny Cash and the Paradox of American Identity (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 10, 28, 154; Grissim, Blues, 7, 13, 98, 116; Flippo, “New-Fangled,” 186; Lange, Hillbilly, 12–13; Pamela Fox, Natural Acts: Gender, Race, and Rusticity in Country Music (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009), 13, 111; and Richard A. Peterson, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 3, 48–50, 178–179, 192–193, 208–210, 219–220.

- “Lord, They’ve Done It All,” 52; Hedgepeth, “Superstars,” 35; Garner, “Ex-Rhodes”; Doggett, Ready, 318; “You Show Me Yours (And I’ll Show You Mine),” track 1 on Kristofferson, Surreal Thing; “Me and Bobby McGee,” by Kris Kristofferson and Fred Foster, track 3 on Kristofferson, Kristofferson; Quinn, “Hits and Myths”; and Kristofferson, “To Beat the Devil.”

- Hurst, “Beats the Devil”; Vance, “Kris Kristofferson,” 328; Mancini, “Good Ole,” 178; Rezos, Rolling Stone, November 12, 1970; Hemphill, “New Nashville”; Quinn, “Hits and Myths”; Korall, “New Breed”; 1972 Showcase, CMHF; Garner, “Ex-Rhodes”; Hilburn, “Troubador”; Al Rudis, “Kristofferson Happy With Misery, Los Angeles Times, August 17, 1971; Lloyd, “Something New”; and Richmond, “Swaggering Lover.”

- Kris Kristofferson, “The Pilgrim-Chapter 33”; Malone and Neal, Country Music, U.S.A., 305; Edwards, Johnny Cash, 7; Kristofferson, “Best of All Possible Worlds”; and 1972 Showcase, CMHF, Frist Library and Archive, Nashville.

- Peter Cooper, Johnny’s Cash and Charley’s Pride: Lasting Legends and Untold Adventures in Country Music (Nashville: Spring House, 2017), 157; Chet Flippo, review of Jesus Was a Capricorn, by Kris Kristofferson, Rolling Stone, January 4, 1973, 66; Garner, “Ex-Rhodes”; Jared Johnson, “Kris’ Ballads Differ From Hee-Haw Set,” Denver Post, January 21, 1972; and Flippo interview with Kristofferson.

- Tom Burke, “Kris Kristofferson Sings the Good-Life Blues,” Esquire, December 1976, 127; Rex Reed, “Partly Truth, Partly Fiction,” Washington Post, April 15, 1973; Patrick Carr, review of Border Lord, by Kris Kristofferson, Country Music, Kristofferson file, CMHF, Frist Library and Archive, Nashville; Paul Nelson, review of Easter Island, by Kris Kristofferson, Rolling Stone, April 20, 1978, 71, 73; Dean Jensen, “Kris’ Border Lord is no Conqueror,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 11, 1972; and Ben Gerson, “Kristofferson; Goin’ Down Slow,” Rolling Stone, April 27, 1972, 50.

- Gerson, “Goin’ Down”; “Mickey Newbury—Country Music Roots,” Country Song Roundup, March 1969, 36–37; Tom T. Hall, The Storyteller’s Nashville (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1979), 84; Grissim, Blues, 102; Rensin, “King Kristofferson,” 26, 32; Alice M. Grant, “The Musicians in Nashville,” Journal of Country Music 3, no. 2 (Summer 1972): 24–44; Wren, “Country Music,” 12; and Pecknold, Selling Sound, 112–113, 168, 238.

- Kristofferson reached number one on the country charts in 1973, but subsequent albums never reached the heights of his earlier work. Malone and Neal, County Music, U.S.A., 378–379, 398–404; Hall, Storyteller’s, 210, 217; Carr, “Circle,” 521; Scherman, “Country”; Drummond Ayres Jr., “‘Crossovers’ to Country Music Rouse Nashville,” New York Times, December 1, 1974; Cobb, “Muskogee,” 86; Jeff Nightbyrd, “Cosmo Cowboys: Too Much Cowboy and Not Enough Cosmic,” Austin-Sun, April 3, 1975, 13, 19; and Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys, 73–75.

- Rensin, “King Kristofferson,” 28; Doggett, Ready, 317–318; Axthelm, “Lookin’,” 66; and Wren, “Country Music,” 13.