“‘We took time, there was no set pattern to how we recorded. We might record all day, go eat a hamburger, and record ’til midnight. I mean we didn’t have no three-hour sessions. No such thing.'”

During the mid-1950s, several amateur musicians living in and around the Muscle Shoals region of Alabama made a leap into the music industry. A few, no doubt, had ambitions fueled by dreams of stardom, while many were simply taken by the sounds of R&B and rock ’n’ roll broadcast over the radio, and others were interested in songwriting and publishing. After initially funneling songs through Nashville, the closest music scene and recording center some 125 miles away, the fledgling Muscle Shoals music industry gained national attention in 1962 after the song “You Better Move On” by Arthur Alexander charted in Billboard, and it continued to grow in prominence throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s.

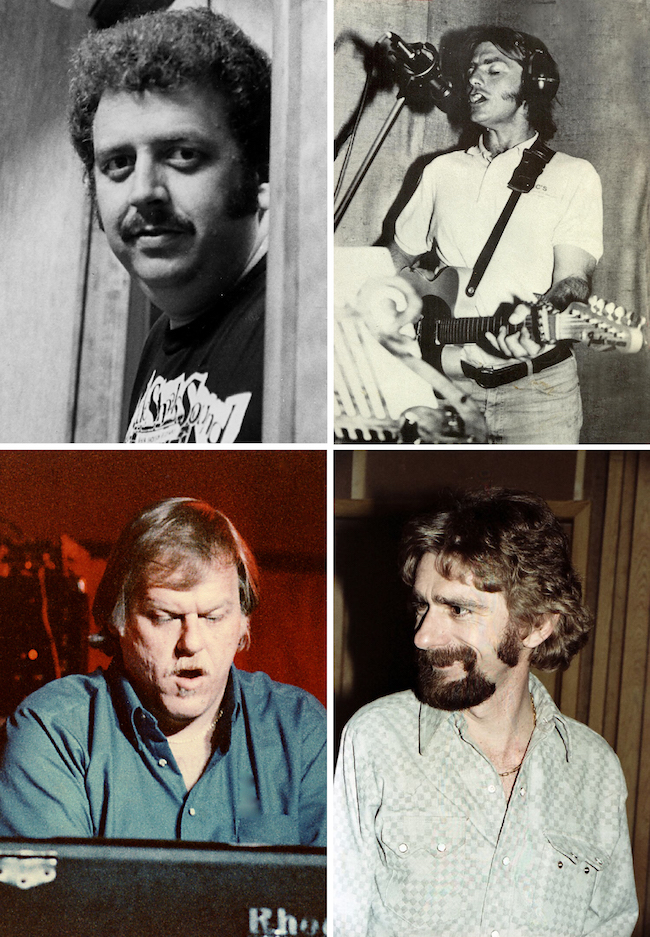

Like many other regional recording centers such as Nashville, Memphis, Cincinnati, and Detroit, the multiple recording studios in Muscle Shoals primarily relied on homegrown session musicians. Two different rhythm sections formed and initially worked as the house band for studio owner and producer Rick Hall at the Florence Alabama Music Enterprise, known as FAME. The first group, active between 1961 and 1964, included bassist Norbert Putnam, keyboardist David Briggs, drummer Jerry Carrigan, and guitarists Terry Thompson and Earl “Peanutt” Montgomery. The second section, which worked for Hall between 1964 and 1969, included guitarist Jimmy Johnson, drummer Roger Hawkins, bassist Albert “Junior” Lowe (later replaced by David Hood), and keyboardist Dewey “Spooner” Oldham (later replaced by Barry Beckett). At times, other musicians, including guitarists Eddie Hinton, Pete Carr, and Duane Allman, supplemented FAME’s second house band.

FAME’s prestige within the music industry and among fans grew through the repeated chart success of hits such as “Everybody” by Tommy Roe (1963), “What Kind of Fool (Do You Think I Am)” by the Tams (1964), and “Steal Away” by Jimmy Hughes (1964). After Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman,” a track produced by Quin Ivy at his Norala Studio in Sheffield, Alabama, reached number one on both the R&B and pop charts in 1966, the Muscle Shoals recording scene took off. Singers traveled to Alabama and recorded with the FAME studio musicians because the artists heard something—a riff or a groove—in the sound of the rhythm sections that appealed to them. The session musicians working at FAME during the early 1960s, followed by the session musicians first known as the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section—Jimmy Johnson, Roger Hawkins, David Hood, and Barry Beckett, aka, “The Swampers”—served as conduits for artists’ ideas, while at the same time providing singers with enough space to retain their own musical identity with more than a hint of the so- called “Muscle Shoals sound.” As Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section (MSRS) bassist David Hood stated in 2011, “With the different artists that we would work with, we always tried to sound like we were that particular artist’s band.”1

In some instances, Rick Hall was the songwriter, but in most cases he was the recording engineer and producer. And in an effort to realize his sound for a song, Hall always relied on local and imported session musicians. In this way, the recording process at FAME in Muscle Shoals was modeled upon the process at Stax in nearby Memphis, where Booker T. and the MGs were the house band, and at Motown in Detroit, where the Funk Brothers played on nearly every track. But popular belief—furthered by Magnolia Pictures’ 2013 documentary Muscle Shoals—deems Hall the single mastermind. As the formal press kit stated:

“At [the] heart [of Muscle Shoals] is Rick Hall who founded FAME Studios. Overcoming crushing poverty and staggering tragedies, Hall brought Black and white together in Alabama’s cauldron of racial hostility to create music for the generations. He is responsible for creating the “Muscle Shoals sound” and The Swampers, the house band at FAME that eventually left to start their own successful studio, known as Muscle Shoals Sound.”

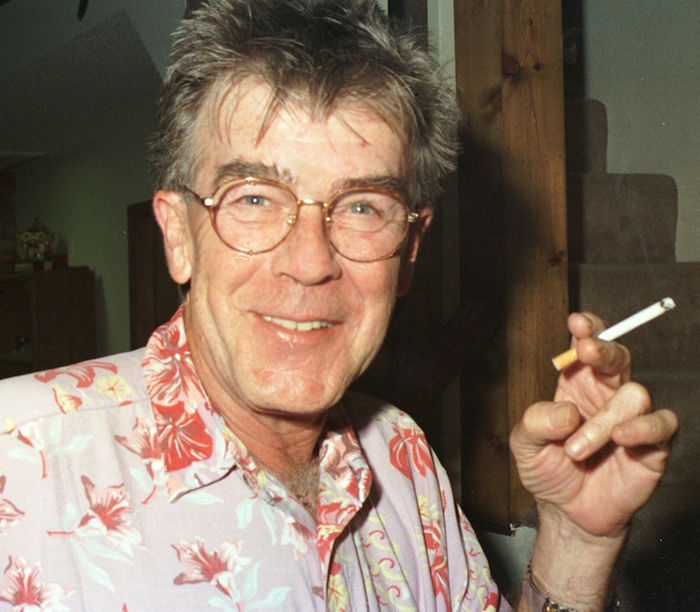

The documentary details Hall’s life—from his days living in abject poverty through his ascendency to a music industry powerhouse. Billboard named Hall “Producer of the Year” in 1971.2

While the information presented in the documentary’s press kit is true, the portrait of Hall as a lone genius is one painted with broad strokes. By primarily narrating Hall’s life, the documentary leaves significant contributions by others on the cutting room floor, including those who established the first commercial recording studio in Alabama that brought Hall to Muscle Shoals, the 1956 song that helped launch the local music industry, and the many studio musicians—not just The Swampers—employed at FAME. Along with Hall’s efforts, each of these individuals and events contributed to the creation and flourishing of the music industry in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Thus, in order to understand how Hall created the “Muscle Shoals sound,” it is necessary to acknowledge two things: the complex network of musicians that formed in Muscle Shoals and Hall’s idiosyncratic recording process.

Rhythm of the River

Access this section via Project Muse.

Catching “A Fallen Star”

For many raised in or near the Shoals who came of age mid-century, music provided a way out from their small town existences. Producer and publisher Buddy Killen reflected in 1993 on the town he grew up in and the prospects he faced after graduating from high school:

Florence was like the dying town in the movie The Last Picture Show . . . With high school graduation upon me, thoughts that I had postponed about the future were now unavoidable. I had to decide what I was going to do in a town where most boys my age either went to work for Reynolds Aluminum [in Muscle Shoals] or moved north to the assembly lines in Detroit. Neither option interested me.6

Like Handy and Phillips before him, Killen left the Shoals in search of his musical fortunes. He moved to Nashville in the early 1950s to pursue a music career that included songwriting, performing as Hank Williams’ bass player, and ultimately, as co-owner of Tree Publishing—one of the top music publishing firms.

In December 1956, Joiner contacted high school senior Bobby Denton, a weekend DJ at WLAY and an amateur musician, to record Joiner’s newly composed song. But in order to record it, Joiner needed a more modern facility. As Denton wrote in his autobiography:

[Joiner] and his associates decided that the only studio and tape recorder in the area that might do an acceptable job was at [radio station] wlay. Even with the good studio and recorder, the setup and conditions were very primitive . . . The recording session was done in about an hour or two using three musical instruments and a local gospel quartet for backup. Of course, we didn’t have the equipment to overdub mistakes, so the complete song had to be recorded all at the same time . . . Also, the engineer who was the radio station disc jockey . . . had to do his work and carry on the regular programming of the station at the same time. In order to give his full attention to our recording, he had to play an extra long record in order to oversee the two minutes and fifty-one second record we were recording. The same process was followed for the song [“Carla”] going on the other side.

The session cost a total of ten dollars: four dollars paid to wlay for “recording serv[ices],” and six dollars to Benny Lott for “engineering recording.”8

Denton’s version of “A Fallen Star” achieved regional success on the radio and made the singing teen a hometown star. More importantly, however, a network of musicians and music industry personnel developed out of this one session between Muscle Shoals and Nashville. “A Fallen Star,” published by Tree Music via Joiner’s Florence connection to Buddy Killen, was also recorded by country musicians Jimmy Newman, Ferlin Husky, the Hilltoppers, and the comedy duo Alonzo and Oscar. Denton’s success also attracted like-minded musicians to Florence. Rick Hall and Billy Sherrill, both from Alabama, began to pitch their original songs to Joiner. Denton recorded “Sweet and Innocent” (written by Hall and Sherrill) and “Back to School” for Judd Records, owned by Jud Phillips (and Sam Phillips’ brother) at Owen Bradley’s Nashville studio in 1958. Killen produced this session that featured veteran studio musicians Boots Randolph on sax and Floyd Cramer on piano, with the Jordanaires and Anita Kerr on backing vocals. The novelty of “Back to School” landed Denton a spot on the September 6, 1958 episode of the Dick Clark Show. The Hall and Sherrill song received wider public recognition when RCA’s Chet Atkins produced Roy Orbison’s cover the same year.9

An Industry Develops

Over the course of 1958 and 1959, an ad hoc music industry developed in Florence, where there was no roadmap for the aspiring songwriters, producers, or musicians to follow. Locals simply forged their own way. Denton befriended Tom Stafford, the manager of the Shoals Theater—a movie house downtown—and together the two began to write songs. “Tom and I were friends when I was fifteen years old,” Denton recently remarked. “I’d come up [to Florence] and we’d play music and write songs, and do stuff like that.” Denton and Stafford set up a small studio located above the City Drug Store on Tennessee Street. Denton recalled in 2011:

[Tom and] I built [the studio] while I was home waiting to go on the road with Jerry Lee Lewis. Me and Tom went to Nashville and got the recorder, and James [Joiner] and Kelso [Herston] paid for it. It didn’t cost but about three hundred dollars. [The studio] had a couple of mics and a Berlant recorder . . . We had that place full up [with musicians] all the time. And right after we got our equipment set up and everything, that’s when Black music was first coming in.

The makeshift studio attracted aspiring teenaged musicians such as Earl Peanutt Montgomery, Dan Penn, Dewey Spooner Oldham, Norbert Putnam, Terry Thompson, David Briggs, Jerry Carrigan, Donnie Fritts, and others who lived locally. Stafford, along with Hall and Sherrill, eventually formed Spar Music, as well as FAME. The musicians who “hung around” Spar talked about music with Stafford and occasionally recorded songs for Joiner’s Tune Records. Early success for Spar included the song “Is a Bluebird Blue?” written by Dan Penn and released as a single by Conway Twitty in 1960. Stafford and Sherrill parted ways with Hall in 1960 and sold him the FAME label for one dollar. By 1961, Sherrill left the Shoals for Nashville, where he initially worked as a recording engineer for Sam Phillips’s studio before he became a top songwriter and producer. Hall remained in Alabama and converted an old tobacco warehouse into a recording facility.10

Several other intangible factors helped Muscle Shoals develop Alabama’s first recording industry. Birmingham, the largest city in Alabama, was an important industrial center of the South through the late 1960s, as many residents worked in the city’s steel mills and blast furnaces. Beginning in 1950, Huntsville, located approximately fifty miles east of Muscle Shoals, became the site of U.S. Army rocket and missile operations. Both Birmingham and Huntsville attracted skilled and unskilled labor seeking to take advantage of the many economic opportunities. In terms of music, these two cities developed thriving nightclub scenes that lured musicians from all over the South, but no recording industry. Before studios opened in the Shoals, Alabama musicians had to travel to Nashville or other cities outside the state to record professionally.11

“We Love This Music”

The musicians who eventually worked for Hall came of age during the 1950s, a time when American teens bonded over R&B and rock ’n’ roll—genres mostly created by Black musicians. For the budding musicians in and around the Shoals, their admiration for music performed by Black musicians was intensely personal and conflicted with the real and perceived race relations in much of Alabama. The racial climate within Alabama, and the burgeoning Muscle Shoals music industry, stood in stark contrast to one another. During the 1960s, as media outlets filled their broadcasts and papers with stories of the clashes between civil rights activists and the Alabama state and local police, the Shoals remained relatively calm. World-renowned artists including Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin, and the Staple Singers recorded there. Throughout the decade and into the 1970s, the Muscle Shoals music industry produced many hit tracks on which Black and white musicians performed together in a cooperative environment based on mutual respect—an environment relatively unknown to other musicians, critics, and fans. In essence, FAME and then Muscle Shoals Sound Studio effectively created inter-racial spaces and tracks within a state better known for racist violence.12

Influenced by diverse musical styles ranging from not only country and R&B to rock ’n’ roll and Broadway, the majority of the would-be Muscle Shoals studio musicians spent years honing their skills performing live. This transformative process from teenaged amateurs into world-class session musicians is central to understanding the development of the Muscle Shoals music industry. From its burgeoning days into the mid-1960s, the musicians often supplemented their income by performing with their respective bands. The story of how Norbert Putnam, bassist for FAME’s first rhythm section, initially became involved in performing popular music typifies many within his generation of Alabama musicians:

This is the late ’50s. I was fifteen years old. And I start slapping bass with Glen Pettis and the Rhythm Rockers. Part of those boys were across the [Tennessee] border in St. Joseph. Glen lived there in Green Hill. My buddy David Briggs, who later becomes my business partner, is down in Killen, Alabama, and he goes to Rogersville High School. And so David and I become friends in the rockabilly band, and that’s pretty exciting. But a year later, we meet young Jerry Carrigan, who is going to Coffey High School [in Florence, Alabama]. And Jerry is putting together an R&B band to play James Brown music, and Ray Charles, Bobby Blue Bland. And I’m thinking I need a Fender bass. So I talk my parents into helping me finance a Fender bass rig. And I get a 1958 Precision, and bass amp, and join up with the Carrigans. And I went from playing rockabilly music to playing the cool music that all the college kids liked. Anybody could dance to James Brown, you know? It’s kind of hard to dance to rockabilly, you know? It’s more like country music. And so, we love this music, and we make the transition.13

Putnam, like many of the Muscle Shoals musicians, developed an interest in music originally performed by Black musicians—an interest that profoundly influenced his career. The perspective provided by Putnam also indicates that by the late 1950s, the sound of rockabilly, at least for him, had become passé. “[I]t’s more like country music,” he said, which was the sound Putnam associated with his parents. Putnam, like many others from his generation, was overtaken by the frenetic and danceable R&B rhythms.

Several other groups, like Hollis Dixon and the Keynotes, who played from 1956 through 1982, served as launching pads for future session musicians. As Dixon recalled in 1987, “Just about everyone played with me, and at one time we were the hottest thing going in the colleges. We played every frat house from Tulane in Louisiana to the University of Georgia in Athens.” Drummer Jerry Carrigan recalled performing during the early 1960s with a group called The Mark V:

This band included David Briggs, Norbert Putnam, Marlin Greene, Dan Havely, Charlie Campbell, and Jerry Saylor. We were extremely popular with the college fraternities, playing every weekend at the big southern universities. Later on, Dan Penn assumed Jerry Saylor’s duty as lead vocalist. I must tell you that was a big turn for the good. Jerry was a great singer, but he lacked the southern Black soulfulness of Dan. Later on, David, Norbert, Dan and me started another band Dan Penn & The Pallbearers. We bought a 1956 Cadillac Hearse to travel in, and travel we did.14

Other Shoals-based groups such as the Del Rays and the Mystics included musicians who would also go on to successful music industry careers.

Inventing Bass Parts from Scratch

While working on demo sessions, first at Spar and then at FAME, the future professionals further developed their craft. Prior to their studio work, the musicians learned their parts by listening to recordings. Performing on original songs, however, was something entirely different. As Putnam recalled:

[We were trying to figure out] how to become players, and of course, playing on demos, we’re playing on original songs. Well, I never played on an original song. “You mean, I’m supposed to invent a bass part from scratch?” This is a major problem. And so, it started us thinking in that direction.

These young studio musicians were eager to work, but there were very few promising local prospects that wanted to record during the late 1950s. “I have to tell you, for the most part, not a lot of talented people were coming up [the] steps [to Spar Music],” said Putnam. “A lot of interesting people came up the steps, and didn’t come back. The one who came up the steps, who really did it for Muscle Shoals, was Arthur Alexander . . . Arthur had something [and] he had some lyrics that sounded good.”

Arthur Alexander, a Black teenager who worked at the Muscle Shoals Hotel, had already performed with a local group called the Heartstrings. Before arriving at Spar, the young singer had been writing lyrics. He needed help, however, with conveying the overall musical sound for his song ideas. With the assistance of pianists David Briggs and Spooner Oldham, Alexander’s songs began to take shape. In 2011, Putnam recounted how Briggs worked with Alexander:

[Arthur] couldn’t write music. My friend David Briggs found the chords to most of those songs. I can remember many times David and Arthur were out there at the upright piano (which was always out of tune by the way), and Arthur would be singing the melody, and David would be playing chords. And Arthur [would say] “No, no, that’s, that’s it! That’s the one. What’s that?” David would write that down. It’s a six minor chord. And it would take ’em a couple of hours. And then we’d all go out there, and try to play with the music David has just come up with Arthur.

Oldham also assisted Alexander with his songwriting. “And on ‘Anna [Go To Him]’ I know Arthur and I sat down at Spar, upstairs over the drug store, and he would sing,” Oldham recalled. “He’d write songs, but he didn’t play an instrument. He would sing to me that song, and I just sort of knew where it went. You know, play it, and we did a little demo.” In 1960, Alexander co-wrote “Sally Sue Brown” with Tom Stafford and Peanutt Montgomery. Alexander recorded the track at Spar backed by Nashville-based Pig Robbins on piano, and locals Ray Barger on acoustic bass, Terry Thompson on guitar, and Jerry Carrigan on drums. The Judd label released the track along with the B-side, “The Girl That Radiates Charm,” during the summer of 1960. The recordings were low- fi at best, and like Denton’s 1956 recording, Alexander’s tracks garnered only regional success. When Alexander brought in a song to Spar called “You Better Move On,” Stafford approached Hall about producing it.15

The track peaked at number twenty-four in the Billboard charts. The success of Alexander’s 1962 track, which Rick Hall produced and recorded at the converted tobacco warehouse, signaled to nearly all those involved that the nascent Muscle Shoals music industry could indeed create a national hit. “‘A Fallen Star’ didn’t bring industry to Muscle Shoals,” declared Putnam. He went on to say:

It might have kept some local people interested, but when Arthur’s song gets in the Billboard charts and starts climbing . . . Now at this point, you have to understand, David Briggs and I had just started college over at what was Florence State [now University of North Alabama]. We were eighteen, nineteen years old. And, when we make this demo for Rick Hall, that becomes the hit record, it was a major force. Here’s Arthur on the Dick Clark show in Philadelphia . . . In the afternoon! We’re going, “Is this really a career opportunity? Or is it just a flash in the pan?”

Alexander’s hit also had an immediate financial and professional impact on Rick Hall. With money earned from the success of “You Better Move On,” he built a new studio (which is still in use today) modeled on several located in Nashville.16

“We Don’t Work By A Clock”

Briggs, Putnam, Carrigan, and Thompson became the house band for Hall’s newly built recording studio, while Peanutt Montgomery occasionally played acoustic guitar to supplement the core quartet. The studio belonged to Hall, who was also the chief engineer and producer, but the musicians initially took their musical direction from Thompson. “[Terry Thompson] was Sergeant Pepper,” recalled Putnam. “He was the leader of the band. He taught David and I a lot about music theory. Not that he knew any[thing] formally. But he had perfect pitch . . . he was so far ahead of us. There wasn’t anything he couldn’t do. If he heard a guitar solo by anyone, he’d just go and pick it up and flawlessly play it. It could be R&B. It could be jazz.” Peanutt Montgomery also spoke fondly about Thompson, saying, “Terry was a great guitar player . . . he was much more advanced than all of us. He could play with his fingers like Chet Atkins, he could also play some jazz, he could play pop, rock. He could play the licks that Scotty Moore played with Elvis Presley.”17

Jimmy Johnson, who at that time worked as a self-described “gopher” for Hall, recalled Thompson’s role: “This guy was an extraordinary guitar player. He had a lot of influence on those early players. Basically, he was their mentor. And as much as Rick was the producer, [Terry] was the guy that really told them how to play, [and] what to play.” Thompson, who also wrote the song “A Shot of Rhythm and Blues,” died tragically at the age of twenty-four in 1965, while struggling to overcome alcohol addiction.18

Hall and the first FAME rhythm section learned how to produce a recording together. “Rick was trying to teach us to think like creative people,” Putnam stated. “Here’s a man, who’s [in his] late twenties, working with a bunch of teenaged musicians, and he can hear in his head a world-class record, and he’s trying to get them to create it.” The recording process, however, was slow. “In the early days,” said Putman, “we weren’t [proficient at recording]. We had to learn it. When we did Arthur’s first three songs, I think it took a day-and- a-half. We probably did thirty, forty takes.” The young musicians eventually improved their time management by using recording techniques employed at other studios. “After a year or so,” Putman stated, “we learned the Nashville method of writing out the numbers so we didn’t have to learn the song. So if you don’t have to learn the song, you don’t have to rehearse. That becomes your roadmap [and] we became very proficient at that.”19

During the early 1960s recording sessions, Hall developed his personal approach to production. In interviews with Putnam discussing the early and mid 1960s, as well as in interviews with bassist David Hood describing sessions at FAME during the mid-to-late 1960s, one thing is clear: Rick Hall was demanding. “[Hall] was a stern taskmaster,” Putnam described.

He’d come out and say, “I want something different!” And we’d say, “Well, how different?” “A lot different.” “Well, could you give us any example? Would it be like . . . ?” And, of course Rick, not being a trained musician, not that it would have mattered or helped, I suppose, couldn’t, in musical terminology, describe what he was hearing in his head. So, we’d just keep trying different things. Hour, after hour. Until he either gave up and took it, or we got it better.

In a 2011 interview, David Hood recalled Hall’s direct approach to producing:

So we’d go in and play and he’d say “No, that’s terrible. No you can’t do this.” And he’d berate us. But we learned because we hated being bitched at so much. We would learn. You would have to . . . It was mono recording, and if you made a mistake you’d have to start all over again. Everybody. So you’d not only get Rick’s displeasure, you’d get everybody else in the group’s displeasure for having to do it again. So it made you learn. It made you learn how to play. I don’t think I really learned to play my instrument until I started recording . . . Rick was brutal. Which was a good thing, in a way, because it made us learn.

Hall’s style of repeatedly recording take-after-take quickly became his production methodology.

While a typical 1960s recording session in a major production center such as Los Angeles lasted three or four hours (a length of time reached through an agreement with the recording labels and the musicians’ union), in Muscle Shoals it was not uncommon to spend nine hours producing just one track. “We took time, there was no set pattern to how we recorded,” recalled Peanutt Montgomery while discussing early 1960s sessions. “We might record all day, go eat a hamburger and record ’til midnight. I mean we didn’t have no three-hour sessions. No such thing.” Hollie West wrote in a 1970 feature article on Muscle Shoals for the Washington Post, “From most accounts, it is common for artists to work on a recording session 14 or 16 hours a day and come back the next day and do the same thing. That’s the way they polish the songs that eventually become hits.” Hall reflected on his approach in 1998, stating, “We had longer hours than Nashville, where you were in trouble if you didn’t get four sides in three hours. I don’t believe anybody can cut four hit records in three hours. I spend a minimum of three hours per song, and I don’t think that’s enough” (original emphasis).20

Alabama’s local headquarters for the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) is located in Birmingham, over one hundred miles from Muscle Shoals. In cities like Nashville, New York, and Los Angeles, the AFM kept a watchful eye on local recording studios and their practices. All of the musicians who worked at FAME were AFM members, but the union rarely checked in on them. Fueled by Hall’s ambition and perhaps their own desires, the studio musicians frequently bent AFM’s rules in order to produce hit tracks. For example, the studio musicians might only sign their AFM time card for three hours, even if the recording session lasted six or nine hours. Because of this practice, the record company or producer financing the session would pay less, which made recording in the Shoals even more lucrative.

Record production at FAME, at least up through the late 1960s, remained a work in progress. Despite the proven chart success of tracks recorded during the 1960s, the Muscle Shoals music industry was a long way from declaring itself “The Hit Recording Capitol of the World,” a slogan adopted by the Muscle Shoals Music Association in 1975. During the roughly three-year period that Briggs, Carrigan, Thompson, and Putnam worked at FAME, they learned first-hand how to produce recordings. Similarly, the second FAME rhythm section—Johnson, Hawkins, Lowe, Oldham, Hood, and Beckett—had also learned to record tracks from Hall, while Hall further refined his skills as an engineer, producer, and music industry executive. The music industry within Muscle Shoals expanded during the 1970s to include a total of seven recording studios—FAME, Muscle Shoals Sound, Broadway Sound Studio, Music Mill, Widget, Wishbone, and East Avalon—where the practice of working many hours on individual tracks continued. In 1977, Al Cartee, president of Music Mill Studios, commented in a newspaper article about why he felt artists preferred recording in Muscle Shoals:

It’s the relaxed atmosphere, the willingness of musicians to come in and work until they get the sound they want that’s made the industry here. None of the studio musicians who lives here ever comes in and says, “Oh, God, I’ve got to cut a session.” That just doesn’t happen here like it does some places. They come in ready and willing to work. We don’t work by a clock. We work all hours of the day and night until we get the sound we want.21

Cartee’s statement discloses that by the late-1970s, the “do whatever it takes” attitude to produce a hit first adopted by Hall in the early 1960s became the preferred Muscle Shoals music industry method, regardless of the studio.

“Arranged by Rick Hall and Staff”

Speaking about session work, bassist Jerry Jemmott once remarked, “Nobody’s an overnight sensation. Years of playing in bars and clubs and dances—this is what you bring to the studio with you. All of that experience comes out in your music.” In the case of the many session musicians who worked in Muscle Shoals, which also included Jemmott, a New Yorker, as well as musicians from Memphis and Nashville, the numerous tracks produced in the Shoals drew upon the musicians’ experiences performing live. All of the musicians highlighted here began their active performing careers as teenagers. Years of doing gigs in bars, at high school dances, and for college fraternities initially infused the tracks cut in Muscle Shoals with urgency and excitement. After settling into regular session work, the players continued to develop their musical skills, further informed by the particular demands of the recording studio. This cyclical process occurred twice in Muscle Shoals during the 1960s. After each FAME rhythm section settled into their own groove as studio musicians, they helped to create some of the most influential tracks in popular music history under the supervision of, and in cooperation with, Rick Hall. In fact, tracks recorded at FAME and released by Atlantic Records during the late 1960s included the phrase “Arranged by Rick Hall and Staff” on the 45-rpm label.22

Working collectively, these individuals helped transform Muscle Shoals from a cultural backwater of the South into a worldwide leader in the music industry by the late 1970s.

A recent review of the documentary Muscle Shoals stated, “The chief architect of [the Muscle Shoals] sound was (and is) record producer Rick Hall . . . As the movie lays out the great musical moments that happened (specifically in Hall’s FAME Studios), it always comes back to Hall and his saga, explaining how he obsessively launched a mission to prove he could become a major somebody in the music industry.” Clearly though, James Joiner, Kelso Herston, Tom Stafford, and Bobby Denton were among the first to launch the Shoals music industry scene. There is no doubt that Hall deserves a significant amount of credit for the musical developments that occurred in Muscle Shoals, and the majority of the musicians interviewed for the film and in other sources express just that. Hall surrounded himself with a group of extraordinarily talented musicians that enabled the self-determined producer to realize not only his vision, but also the musical dreams of those around him. Working collectively, these individuals helped transform Muscle Shoals from a cultural backwater of the South into a worldwide leader in the music industry by the late 1970s.23

Christopher Reali earned a PhD in Musicology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His dissertation, “Making Music in Muscle Shoals,” combines musical analyses, new interviews, and archival materials to explain how and why the music recorded in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, became integral to the sound and culture of 1960s and ’70s America. He teaches at several universities in the Raleigh- Durham, NC area.NOTES

I wish to thank John Brackett, Kristen Turner, and the anonymous readers who made valuable comments on early drafts of this article.

- In brief, the “Muscle Shoals sound” represents a sound, a recording process, and a marketing term. During the 1960s, many record labels and regions were identified with a particular “sound”—the “Motown sound,” the “Stax sound,” or the “Bakersfield (California) sound.” As a marketing term, the phrase “Muscle Shoals sound” does not appear in print until 1969, after Jimmy Johnson, Roger Hawkins, David Hood, and Barry Beckett open their recording studio named Muscle Shoals Sound. In 1969, Hall characterized the “Muscle Shoals sound” as “funky, hard, gutty, down to earth. It’s warm and heartfelt with a dance beat. No gimmicks or sound tricks.” Hall, however, consistently relied on the use of echo to enhance the spatial characteristics of recordings made at FAME, which is a “sound trick.” (Other studios also relied on echo.) For a detailed analysis of the “Muscle Shoals sound,” see Christopher M. Reali, “Making Music in Muscle Shoals” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2014), 41–124. The Hall quote is from Newsweek, “Muscling In,” September 15, 1969, 90; David Hood interview with Christopher Reali, May 24, 2011. Unless indicated otherwise, all quotes by Hood are from this interview.

- For more information on the recording process at Stax, see Robert M. Bowman, “The Stax Sound: A Musicological Analysis,” Popular Music 14, no. 3 (1995): 285–320. For information about the recording process at Motown, see Andrew Flory, I Hear a Symphony: Motown and Crossover r&b, University of Michigan Press (forthcoming). Andy generously shared the manuscript with me in advance of its publication; “Complete Press Kit,” accessed May 7, 2015, http://www.magpictures.com/presskit.aspx?id=827e9dcf-98b7-4b01-a504-81bdf2f9acb7. “The Swampers” collectively refers to Jimmy Johnson, Roger Hawkins, David Hood, and Barry Beckett. When Johnson, Hawkins, Hood, and Beckett opened their own studio in 1969, they christened themselves the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. Several years after their studio opened, they were given the nickname “The Swampers,” which was immortalized in the 1974 Lynyrd Skynyrd song “Sweet Home Alabama.” This group of musicians was never referred to as The Swampers while working for Rick Hall at FAME. In April 2015, Hall published an autobiography, The Man from Muscle Shoals: My Journey from Shame to Fame (Monterey, CA: Heritage Builders Publishing, 2015). This source, however, was published as this article went to press.

- Information about native tribes who inhabited the Shoals can be found in William Lindsey McDonald, Lore of the River: the Shoals of Long Ago, 3rd ed. (Florence, AL: Bluewater Publications, 2007). The city of Florence provides information about the Florence Indian Mound online. See “Native American, Florence Indian Mound and Museum,” accessed April 13, 2011, http://www.visitflorenceal.com/attractions/native-american; William Lindsey McDonald, Lore of the River. This quote appears in “The Singing River Mythology at the Shoals,” located on the back cover of the book; Terry Pace and Robert Palmer, “Moved by the Spirit,” Times Daily, August 1, 1999, 2. Pace generously gave the author a rare hardcopy of this article, which was included in a special supplement about the Muscle Shoals music industry. The Shoals Chamber of Commerce reprinted portions of the supplement on their website. See “Muscle Shoals Music,” http://www.shoalschamber.com/live/muscleshoalsmusic.html, accessed November 20, 2010. Also see Randy McNutt, Guitar Towns: A Journey to the Crossroads of Rock ’n’ Roll (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), 126. Director Freddy Camalier makes the “Singing River” myth and the general concept of water central to his 2013 documentary, Muscle Shoals (Magnolia Pictures, 2013); See Bernard Cresap, “The Muscle Shoals Frontier: Early Society and Culture in Lauderdale County,” Alabama Review 9 (July 1956): 188. Cresap’s study noted, “A scant concern for the fine arts may be attributed to crude frontier conditions, perhaps,” 212.

- Sheffield: City on the Bluff 1885–1985 (Sheffield, AL: Friends of Sheffield Public Library, 1985), 60; Preston J. Hubbard, “The Story of Muscle Shoals,” Current History (May 1958): 265.

- T. S. Stribling, The Store (New York: Literary Guild, 1932).

- Buddy Killen, By the Seat of My Pants (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), 56–58.

- Herston eventually moved to Nashville where he became a top session guitar player. During the 1960s, he then served as Vice President for United Artists Nashville operation, and helped to establish Capitol Records as a leader in country music. Herston served as the Music Director for the television show Hee Haw. In the 1970s he established a highly successful jingle writing company; I acquired these dates from an undated typed document printed on Tune Publishers Incorporated stationary found in the James Joiner file, located at the Alabama Music Hall of Fame (AMHF). The individual documents housed in folders at the AMHF are not numbered or indexed. The subject files are organized simply by last name (i.e., Jonier, James). Information found in Love Lifted Me, Bobby Denton’s autobiography, supports these dates. Other partners in Tune Records included Walter Stovall and Marvin Wilson. Bobby Denton, Love Lifted Me: A Story of Life, Love and Tragedy (Muscle Shoals, AL: Falling Star Publishing, 2009); Dexter Johnson, Jimmy Johnson’s uncle, built the first recording studio in his Sheffield garage in 1951.

- Denton, Love Lifted Me, 41; This information obtained from a photocopy of Tune Records’ check register, located in the “James Joiner” file at the Alabama Music Hall of Fame. In his autobiography, Denton incorrectly attributes Joe Heathcock as the engineer. The 1956 and 1957 Broadcasting Yearbook lists Bobby Lott as the chief engineer for WLAY. The yearbooks are accessible at the website, American Radio History, “Broadcasting Publications, Broadcasting Yearbooks: Directory of AM FM TV stations, regulations and suppliers from 1935 to 2010,” http://www.americanradiohistory.com/Broadcasting_Yearbook_Summary_of_Editions_Page.htm, originally accessed February 21, 2013.

- Denton retired from music after a few weeks on a fall tour sponsored by Clark.

- Bobby Denton interview with Christopher Reali, May 31, 2011. Unless indicated otherwise, all quotes by Denton are taken from this interview; Christopher S. Fuqua, Music Fell on Alabama: The Muscle Shoals Sound that Shook the World (Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2006), 30; Sherrill co-wrote “The Most Beautiful Girl,” “Stand By Your Man,” “Almost Persuaded,” and many others. His many production credits include “Behind Closed Doors” for Charlie Rich, “Stand By Your Man” for Tammy Wynette, and “He Stopped Loving Her Today” for George Jones; For more information about the history of the Muscle Shoals music industry, see Fuqua, Music Fell on Alabama; James Dickerson, Mojo Triangle: Birthplace of Country, Blues, Jazz and Rock ’n’ Roll (New York: Schirmer Trade Books, 2005); Peter Guralnick, Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom (New York: Harper & Row, 1986. Reprint, Boston: BackBay Books, 1999).

- See Jane DeNeefe, Rocket City Rock & Soul (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011) for an ethnographically based history of the 1960s Huntsville music scene.

- For more information about the mixing of black and white soundscapes in the Shoals, see Reali, “Making Music in Muscle Shoals,” 186–227; and Les Back, “Out of Sight: Southern Music and the Coloring of Sound,” in Out of Whiteness: Color, Politics, and Culture, ed. Vron Ware and Les Back (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 227–253. For a 2015 source that addresses similar issues published after this article went to press, see Charles L. Hughes, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

- For information about studio musicians working in the South during the 1950s and ’60s, see Roben Jones, Memphis Boys: The Story of American Studios (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010); Tracey Laird, Louisiana Hayride: Radio and Roots Music Along the Red River (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); and Rob Bowman, Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records (New York: Schirmer Books, 1997); The members of the next FAME house band (1964–1969), Jimmy Johnson, Roger Hawkins, Junior Lowe, David Hood, Dewey “Spooner” Oldham, and Barry Beckett, also performed in local bands; Norbert Putnam interview with Christopher Reali, June 10, 2011. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes by Putnam are taken from this interview. For more information about the influence of rock ’n’ roll and r&b on southern teens, see Michael Bertrand, Race, Rock, and Elvis (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2000).

- Barney Hoskyns, Say It One Time for the Brokenhearted: Country Soul in the American South (London: Bloomsbury, 1998), 95; “Jerry Carrigan Interview,” http://gracelandranders.dk/default.asp?page_id=166, accessed January 3, 2012.

- Spooner Oldham interview with Christopher Reali, June 2, 2011. Unless indicated, all quotes by Oldham are taken from this interview; Oldham commented that the pianist on Alexander’s 1962 recording of “Anna (Go To Him)” for Dial Records, likely Floyd Crammer, copied his original piano riff first recorded on the Spar demo; Richard Younger, Get a Shot of Rhythm and Blues: The Arthur Alexander Story (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2000), 34; “Sally Sue Brown” backed with “The Girl That Radiates Charm,” Judd S-878 1020, 1960.

- Alexander is the only songwriter to have his songs covered by The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan. The Beatles recorded “Anna (Go To Him)” in 1963; the Rolling Stones recorded “You Better Move On” in 1964; and Bob Dylan recorded “Sally Sue Brown” in 1988.

- Earl “Peanutt” Montgomery interview with Christopher Reali, May 27, 2011. Unless indicated otherwise, all quotes by Montgomery are from this interview. Montgomery acquired the nickname “Peanutt” while working at WOWL, a television station in the Shoals. Montgomery explained to me the odd spelling this way: “When I recorded for [the label] Tollie, I recorded under Peanutt Montgomery, III. And I told them put the third on there, I spelled it with two T’s. I said my grandpa was a Peanutt, my daddy was a Peanutt, and I’m the third one, that’s what I told them.”

- Jimmy Johnson phone interview with Christopher Reali, November 8, 2010. Unless indicated otherwise, all quotes by Johnson are taken from this interview.

- The “Nashville method,” also known as the Nashville Number System, uses numbers to represent scale degrees and their corresponding chord. This system allows for easy transposition to any key in order to accommodate the range of a vocalist. In the key of C, the numbers represent: C=1, D=2, E=3, F=4, G=5, A=6, B=7. For example, a progression labeled 1 1 4 5 and performed in the key of C would be C C F G; transposed to the key of G it would indicate G G C D.

- Hollie I. West, “The Stars are Falling on Alabama, They Dig Muscle Shoals,” Washington Post, February 15, 1970, K1; Hoskyns, Say It One Time, 106.

- Putnam, Briggs, and Carrigan would go on to become members of the “A-list” session musicians in Nashville during the mid to late 1960s and 1970s performing on and eventually producing numerous tracks; Because the Swampers were in such demand and the tracks they appeared on often became hits, they frequently negotiated to receive royalty payments in exchange for lower session fees; Glenn Stephens, “Watch Out Nashville, Muscle Shoals Says,” Tri-CitiesDaily (Florence, AL), February 20, 1977, 43.

- Randy Poe, Skydog: The Duane Allman Story (San Francisco: Backbeat Books, 2006), 88.

- Isaac Weeks, “White Guys: The Origin of the Muscle Shoals Sound, and a New Julian Assange Film,” Indy Week (Durham, NC), October 16, 2013, 33; FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound Studio (MSSS) continued to produce hits up through the end of the 1970s. The Swampers moved their studio in the late 1970s from 3614 Jackson Highway to an old Navy Reserve building located at 1000 Alabama Avenue. In 1985, they sold that facility to Malaco Records, a Jackson, Mississippi–based company. During the 1980s, Hall turned his attention to country music and publishing. Today, FAME still operates in its original location. The original MSSS was recently purchased by the Muscle Shoals Music Foundation, which is raising funds to restore the studio. The Shoals is currently home to several operating studios, including Noiseblock, owned by Gary Baker, a Grammy Award–winning songwriter.