“The ruins remain overgrown with castor plants, which can be, alternately, an excellent source of sustenance if cooked properly or a natural source of cyanide.”

The traditional Bahamian response to the request for someone’s name, upon introduction, is typically their name preceded by “I name.” Such a title seemed fitting for this project after I was supernaturally introduced to the story of an enslaved woman by the name of Charlotte—one of two women charged as accomplices in orchestrating the 1831 Bahamian revolt of enslaved peoples at the the Golden Grove plantation in Port Howe, Cat Island, Bahamas—a woman who has long lived in the shadow of Dick “Black Dick” Deveaux, the enslaved man who was hanged for coordinating the uprising and attempted murder of the plantation owner, Joseph Hunter.

Cat Island is synonymous throughout the archipelago with obeah, an indigenous African cultural practice often associated with the dark arts; it’s the island among the Bahamas that held onto its Africanisms the longest, which is understandable with its plantation ruins numbering more than thirty. The practice of obeah in the British colonies was outlawed in the 1800s because obeah in the hands of the enslaved Africans was a liberatory praxis. It is impossible to extract all its tenets from Bahamian folk culture. The use of medicinal plants, for example, looms large in our folkways; plants can be medicinal or poisonous depending on whose hands they are in. It was on my quest for more information about obeah that I stumbled upon Charlotte’s story.

The short story of the uprising is one of an egregious exercise of power by Joseph Hunter during the Christmas week of 1831, arising from a dispute about working days. A week-long standoff culminated in Dick firing at Hunter in self-defense. In the resultant chaos, Hunter aimed his weapon at an enslaved woman named Linda, and Charlotte came to her defense armed with a rock. Exacerbating the tensions, during the week leading up to the uprising, Hunter accused Charlotte’s sons of theft; they were among the ten imprisoned and charged for their “crimes.” Nine of them were acquitted because of the close proximity to Emancipation (1834) to avoid the ruffling of abolitionist feathers. Black Dick paid for his role with his life.

Dr. Allan Meyers, a professor of anthropology at Eckerd College who has been researching plantation ruins in Cat Island for many years, discovered that Charlotte had long been fighting for the freedom of the enslaved at Golden Grove—quite possibly through the use of obeah. Meyers shared the transcript of a letter from Joseph Hunter’s daughter, Sarah Poitier, dated 1832, giving account to her brother—then living in the United States—of the fallout of the revolt: “With great difficulty we got an overseer to go up and take all the felons up except Charlotte & as she attempted to poison both Master and Mistress five years ago.” Hunter and his daughter died in 1838, within weeks of one another. Details of their deaths are not provided, which leaves open the possibility of the involvement of obeah, a frequent occurrence according to historical records throughout the region.

The ruins remain overgrown with castor plants, which can be, alternately, an excellent source of sustenance if cooked properly or a natural source of cyanide—an altogether poetic occurrence (all things considered) as Charlotte steps from the shadows.

Here, Feleshia Hunter, descendent of the enslaved peoples of Golden Grove, embodies Charlotte standing among the castor plants that have taken over the ruins.

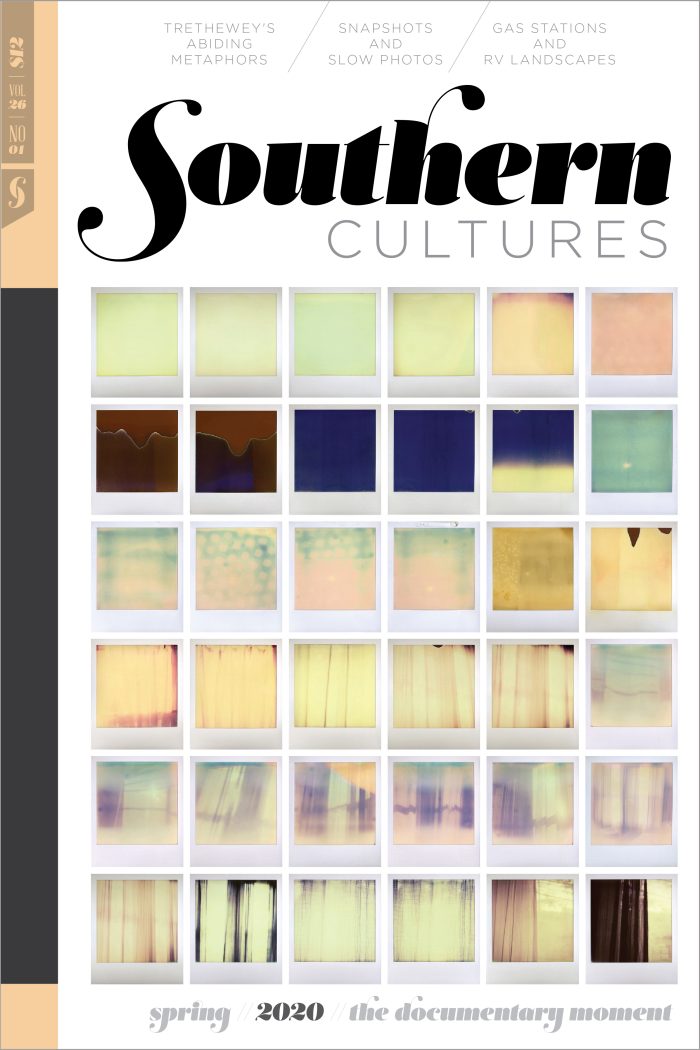

This piece, from our Snapshot series, first appeared in the Documentary Moment issue (vol. 26, no. 1: Spring 2020).

Tamika Galanis is a documentarian and multimedia visual artist. Emphasizing the importance of Bahamian cultural identity for cultural preservation, Tamika documents aspects of Bahamian life not curated for tourist consumption but for the historical archive. Tamika’s photography-based practice includes traditional documentary work and new media abstractions of written, oral, and archival histories.