“’Lisa, Keep on being a rock star!’ my friend Emily wrote. ‘You’ve proven to the universe that you are not to be messed with. Now you can do anything you want.’ Anything—except, apparently, remember.”

The earliest thing I remember after the hemorrhage is a moment that I can’t place in time and that may not have even happened. I was taken into a hospital room in Wilmington, North Carolina, guided there by my friends Christian and Jonathan, who were visiting me. As we stood in the entrance to the room, I looked at my partner Matt, who was stooped over a table filling out forms. Christian or Jonathan earnestly told me that Matt was taking good care of me; that he was showing himself to be what everyone already knew him to be, a good man who loved me.

A few weeks later, my friend Leila and my daughter Amelia were with Matt and me when my hairdresser came to my hospital room in Chapel Hill. Matt had found her contact information in my phone and arranged for her to confront the tangled mass of my long brown hair, practically impossible to penetrate after the weeks I had spent lying in bed. Who could think about brushing my hair when I might never wake up? But now I was awake, grimacing with every pass of the comb and eyeing both Leila’s and Amelia’s short, boyish hairstyles. “Just cut it off,” I decided. The resulting pixie haircut was kind of cute, I think I thought—but alas, half of it was buzzed off the next week, when surgeons unexpectedly opened my head for a second surgery.

After that operation—to install a drain for excess brain fluid—I remember things normally. But whatever I might have remembered for four weeks before it, with only these two exceptions, is gone.

In the early morning of May 29, a brain aneurysm—a bulge in one of my cerebral arteries—burst. Matt and I had driven to Wrightsville Beach for a little vacation the afternoon before. We would have liked to get there a couple of weeks earlier, when our semesters had ended and the weather was already hot, but it seemed like his work as professor and advisor and mine as chair of the History Department, plus needs of our high school and college-age kids, kept us putting it off. Still, we were getting away for three nights, starting May 28.

That first night was glorious. The weather was perfect—warm and breezy—and we’d found a comfortable Airbnb place on the less inhabited end of the island. We had a drink and brought our portable chairs out to the beach to watch windsailers. Later, we rode our bikes into town for another drink at a dive bar followed by seafood dinner at a restaurant next door. That night, we fell asleep exhausted, tipsy, and full of love. That’s the last thing I remember before the hospital in Chapel Hill, weeks later. Matt says that he awoke early in the morning to what sounded like a wounded animal. I wasn’t in the bed. He found me in the living room hyperventilating and barely conscious. I gather I had woken up and left the bed, probably with what doctors describe as “the worst headache of your life.” Matt saved my life by calling 911, then the EMT folks saved my life by getting me quickly to the New Hanover Regional Hospital in Wilmington, and then doctors and nurses saved my life by diagnosing the hemorrhage through an angiogram and performing surgery to repair it.

A nurse, Karine, whose self-appointed job is to help people whose loved ones aren’t going to make it, counseled Matt to summon my parents from Louisiana and children from Chapel Hill and Baltimore, which he did. Over the next couple of days, in fact, he alerted a lifetime’s worth of family and friends, and he kept them posted during much of my ordeal.

When I first got to the hospital, a doctor told Matt that I had a 50 percent chance of surviving the night. Later, a neurologist told him that of people who suffer cerebral hemorrhages, 1/3 die right away, 1/3 have significant brain damage, and 1/3 make a full recovery. Dr. Doss, who performed the surgery, came out to talk to Matt and held up his two fists. “This is good,” he said, pointing to his left, “and this is bad,” pointing to his right. Then he moved his left fist far onto the other side of the “bad” fist. “And this is where Lisa is.”

People say that my quick recovery is miraculous. I fell into the lucky third. But I lost all memory of approximately four weeks.

Out of all of my resentments about “the incident,” as some of my friends are calling it, I am most offended by the loss of memory. Maybe it is because I am a historian by profession, or because for years I have tended my own and my family’s history through documents, photos, and story. Soon after I came back to myself after the second, hydrocephalus surgery, I realized that I could not remember anything since that lovely night on Wrightsville Beach before I had entered the hospital. Since then, I have been piecing together the nature of that loss, the period of time that it encompasses, and what I likely don’t remember. I have been using the tools I developed as a historian: interviews, retrieval of relevant documents, analyses of written evidence. And I have been probing why it is that I am so concerned about the loss of what are probably banal memories of unexciting events.

My mother, who quickly flew from Louisiana to my hospital room in Wilmington, is convinced that it is better if I don’t remember. She still seems traumatized by seeing me struggle against the breathing tube down my throat, which could only be removed after I could breathe on my own when I was conscious enough to feel it as suffocating me. Why would I want to remember that? Or the cold water pads strapped around my legs and torso to combat my fever, which made me shiver so much that another space-age device had to be layered on top of them for warmth. I spent days both uncomfortably cold and barely warm at the same time. Isn’t it better if my memories of that time are erased? What is it that I need to know?

The why questions are easier than the what. I want to know what I missed because the other people in my life did not miss it. They relate to me on the basis of having been through the trauma of my illness, near death, and treatment—none of which I remember.

Historians are a bit like detectives in that we search for evidence for actions and events in the past. I’ve written a biography about someone who left scarcely a paper trail in nineteenth-century Africa, so I ought to be able to put together a month of my life in modern America, with all of our record keeping. Since I left the hospital four months ago, I’ve been obsessed with reconstructing the four weeks that I can’t remember. I’ve perused my medical records, interviewed my family and friends, read Matt’s journal, scanned his photos, checked my phone and email for messages that he may have sent through my accounts. I read each of the 126 cards and letters that came for me, which Matt saved in a cardboard box, and sent an email response to most folks. One of those cards still lives in my book bag to inspire me. “Lisa, Keep on being a rock star!” my friend Emily wrote. “You’ve proven to the universe that you are not to be messed with. Now you can do anything you want.” Anything—except, apparently, remember.

“Lisa, Keep on being a rock star!” my friend Emily wrote. “You’ve proven to the universe that you are not to be messed with. Now you can do anything you want.” Anything—except, apparently, remember.

I know the basic narrative of what happened to me. After that frantic 911 call, I was taken in an ambulance to the hospital. Dr. Doss, the neurosurgeon, wrote in my record: “poor grade but young and appears salvageable.” That afternoon, he put a thin metal coil into my brain to repair the hemorrhage. Two days later, I responded to commands and began to communicate. For a reason I can’t remember now, I asked if I had had a heart transplant. (Another time, when a nurse asked if I knew why I was in the hospital, I responded, Yoda-like, “Medical mishap.”) After two weeks in intensive care, I was moved to the hospital’s progressive care unit, where I spent another week. In mid-June, Matt had me transported by ambulance to residential rehab at UNC Hospital in Chapel Hill, close to where we live. After a week there, I had the surgery for hydrocephalus. Immediately after that surgery, my brain began to work normally again. I stayed in rehab one more week before heading home, and that week is the only part of this saga I can remember.

In addition to recovering the paper trail, I also did fieldwork to find out what I’ve missed. As an American historian of Africa, I know about fieldwork: I know that one needs to be in a place where something happened to develop new insights and questions, to see the physical environment and make conceptual connections, to encounter the right people to ask questions of. I lived in Nigeria for a year when I was working on my PhD dissertation, and I’ve done shorter stints of foreign fieldwork since then. But it didn’t occur to me until Matt and I took a recent trip back to Wrightsville Beach, intended as the proper beach vacation that we never had last summer, that I realized I was also doing fieldwork there, asking questions prompted by the landscape and looking for informants.

We were sitting in our beach chairs gazing at the ocean when a lifeguard on an ATV drove by and Matt snapped to attention. “That’s him,” he said, “that’s the first person who arrived when I called 911.” It took a few beats after we flagged him down for the lifeguard to understand who we said we were, and then he began to beam. He hugged us both and recounted how worried he had been when he responded to the 911 call and found me as my body was shutting down. We met properly this time: his name, memorably, is John Skull. He seemed thrilled and relieved to meet me alive, because, he said, he has worried about me every day since then.

When we visited Wrightsville Beach, Matt and I also reconnected with Karine and another emergency room nurse, Alexandra, who had taken care of me that first frantic day. She had displayed another remarkable feat of memory, in fact. Matt had followed the ambulance to the hospital, but by the time he arrived, they had already whisked me away—somewhere. He gave my name to the attendant, but there was no response. After perhaps fifteen minutes, he insisted that there must be someone of my description in the ER. At last, Karine helped him locate me. “That’s Lisa Lindsay!” Matt announced when he was finally taken near my stretcher. “Lisa Lindsay?” asked the nurse, Alex, who was attending to me. “Does she teach at UNC?” Alex, in fact, had recognized me as the professor of a first-year history seminar she had briefly enrolled in, two hundred miles away and some nine years ago.

When Karine and Alex entered the restaurant to meet us for dinner recently, still in their scrubs from their just-finished hospital shift, I immediately recognized Alex. She is a brunette in her late twenties, with smiling eyes and dimples. But I recognized her from the class she took with me in 2010, not from the hospital—which is a blank in my mind.

Like John Skull, Karine and Alex could hardly believe I am alive, and walking and talking. That day in the emergency room, when Matt had turned away from them, the two women’s eyes had met and they’d shaken their heads with pessimism. That’s what they remember.

Maybe I’m obsessed with my memory because for the past year, my work life has been focused around questions of memory. Indeed, when my fellow department chairs from UNC heard about my brain hemorrhage, they assumed it was the stress of the campus situation that had almost killed me. I’m a historian, and so the past is always part of my work life. But on August 20, 2018, the first day of the fall semester, which was my first term as chair of the UNC history department, activists pulled down the campus statue known as Silent Sam. There had been demonstrations calling for the statue’s removal for more than a year. Sometimes demonstrators quoted Julian Carr, the wealthy local industrialist who had helped to commemorate the statue when it was erected in 1913 by bragging of horsewhipping a “negro wench” near that very spot. The Confederate soldier depicted in the statue meant different things to different people, but for people of color especially, Silent Sam was an enduring symbol of the racism that was so pervasive in UNC’s history.

The controversy had cooled a bit by the following spring, but when I had my brain hemorrhage in May, it was obviously on my mind. My department was courting for an endowed professorship a historian whose specialty is the comparative study of truth and reconciliation commissions, and if he were to accept our offer, he would help to lead an examination of UNC’s own painful legacies. He and his wife were planning to visit Chapel Hill a few days after my beach trip, and I was helping to plan events that I hoped would dazzle them. I don’t remember any of this, but Matt tells me that as soon as I began to talk, a couple of days after first losing consciousness, I wanted to know about that historian. Who was hosting him in my absence? How could we convince him to come to UNC?

According to my hospital file, what I suffered was a PICA aneurysm, which I discovered from an internet search is a bulge in the posterior inferior cerebellar artery and is extremely rare, even for brain aneurysms. The cerebellum, where my brain bleed took place, is a relatively small area of the brain in the back of the head that controls coordination, balance, and equilibrium. No wonder my walking has been so awkward—and no wonder the physical therapist I saw after my discharge was so concerned about it. Dr. Doss, the neurologist who saved my life in Wilmington, told Matt that the brain area where I bled was bad because it could lose a lot of blood, but good in the sense that, if I survived, damages there could be reversed. I think that means that my coordination can be improved. In fact, I was released from post-hospital physical therapy three weeks into a seven-week plan, with the rationale that I had “achieved my goals.” Really? I didn’t even know I had physical therapy goals—to me, my goals were to fill in the gaps of my consciousness.

But the cerebellum has very little to do with memory. It does control procedural memory, which the body learns through repeat practice. Playing a musical instrument is the example frequently given of procedural memory—and yet I can still play the saxophone, which I learned to do in high school and have maintained through the decades since then. I convened a band rehearsal a week after leaving the hospital, and I’ve played gigs since then. Rather, I can’t remember my four weeks in the hospital, and I have some lapses these days in forming new memories. After Matt tells me what we’re doing for dinner tonight, for instance, I may well ask him later what we’re doing for dinner tonight. Memories formed before the incident seem to be intact: I can recall events from my childhood, things I learned in graduate school, or even the last glorious night in Wrightsville Beach before my brain started to bleed. And my memory now largely works, especially in my academic life. But where did I leave my keys this morning?

Medical literature shows a clear correlation between hospitalization and “cognitive decline,” although that correlation has only been studied in patients older than sixty-five. But it’s not just being in the hospital that causes mental problems for patients: the intensive care unit is specifically associated with delirium both in the hospital and, for about a quarter of patients, for up to a year afterwards. It’s possible that some of my memory loss was related to treatment in intensive care and being in the hospital more generally.

I definitely had ICU psychosis, or “brain fog,” those first two weeks in the Wilmington hospital. Perhaps it was because with the lights on all the time I never got enough sleep, especially because I was tested for brain functioning every hour. Matt and our kids make light of it, especially when they recall the ridiculous things I said in my disorientation. When asked the names of my daughter and son, I said “Michelle and Pius,” instead of Amelia and Julian, for no reason I can imagine. Our dogs, a neurotic Pitbull mix and a prissy Dalmatian, I referred to as “Bluster and Olive,” though those are not their names. Once I narrated a long story, as if I were dreaming but awake, about Maggie, the Dalmatian, running through a park and hopping up on a band shell, where she grabbed a microphone and entertained the crowd with her rendition of “You Make Me Feel Like a Natural Woman.”

After I left the ICU, people say I began to behave more normally, but I can’t remember that either, and it wasn’t entirely normal. I insisted to a colleague who came to visit me that I would soon make my scheduled appearance at a conference in Nigeria, even though I couldn’t walk on my own.

Memory involves two processes: imprinting and retrieving. I realize now that I wasn’t committing anything to memory during those initial weeks in and after the ICU, a time that I likely will never remember. During that period, my brain continued to produce and fill with, but not drain, fluid. It seemed at first like my condition was improving, because I was relearning to walk and holding conversations with visitors. But shortly after moving to Chapel Hill, my cognitive decline was obvious.

It took a second surgery, finally, for the lights to come on in my brain.

A good friend of mine, Luise, spent nearly a year in the hospital several decades ago, in treatment for a disease from which she has largely recovered. The disease affected her limbs and her breathing, but she told me that she also has memory lapses from that time. Even more strikingly, she remembers visitors and conversations that she later found out never took place.

Luise is a brilliant historian, and some years ago she wrote a book called Speaking with Vampires about oral history and memory. In it, she recounted stories that people told over many decades in different parts of East and Central Africa that differed in the details but all involved people who took others’ blood against their will. Most of the vampire stories—which sometimes involved firemen, sometimes colonial officials, sometimes ambulances—are too fantastic to be true, but they were widely circulated and retold nonetheless. The core argument of the book is that rumors should and can be treated as historical sources. Even when they are not literally true, they say something about the context in which they circulate and about people’s assessment of the world in which they live.

Given her published defense of the value of rumor, I was a little taken aback by Luise’s dismissal of my concern about losing my memory. Isn’t memory valuable? That’s when she told me about being sure certain things had transpired in the hospital, only to find out they never took place. “No memory is true,” she insisted to me.

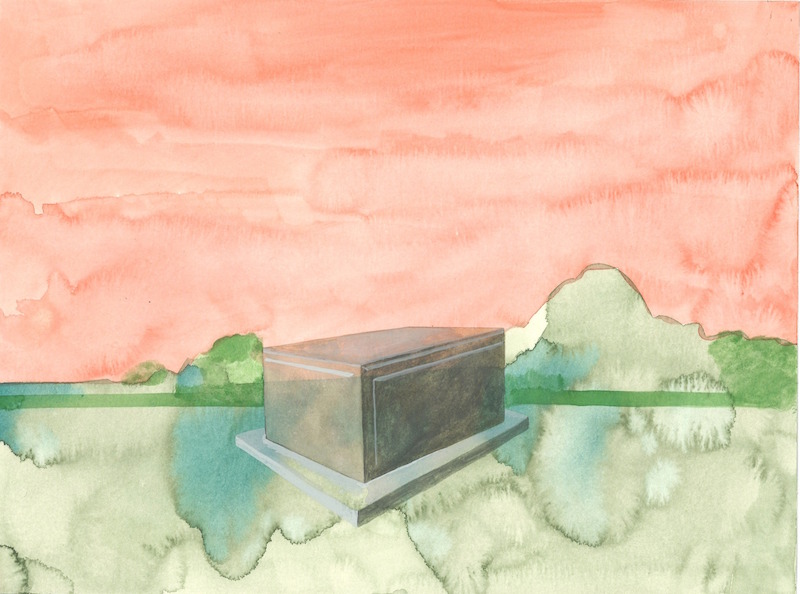

The book I recently published—the “life and times” biography of an African American who moved to West Africa in the 1850s—also has at its core a memory that turned out not to be true. His family’s oral history, passed down for generations, is that when this man, James Churchwill (or “Church”) Vaughan, first arrived in what is now southwestern Nigeria, he recognized his father’s “tribal marks” on people he saw there. (“Tribal marks,” or “country marks,” were cut facial scars that marked people’s belonging in particular communities and geographic locations, especially during the era of the slave trade.) This meant that Church had now returned to the community from which his father had been taken, in a sense reversing the Atlantic slave trade. The story was published in Ebony magazine in 1975 to highlight the rare but enduring connections between Nigerian and American branches of the Vaughan family. When I read it in the course of my research, I became convinced that it revealed something profound and exciting about American history and the history of the African diaspora. The descendants of enslaved Africans preserved specific memories of their places of origin; and at least one African American man was able to undo some of the alienation of slavery by finding his ancestors’ people.

I spent the next couple of years tracing records of Church Vaughan’s life in the United States and Africa—a difficult feat since he did not leave much writing behind. I was awarded prestigious fellowships because others also sensed that this might be an important, formerly neglected piece of American and world history. But my genealogical research revealed a bombshell: Church’s father was born not in Africa but in Richmond, Virginia. Thus, he is extremely unlikely to have had the “tribal marks” that later generations of his family “remembered.” Church Vaughan did in fact move from South Carolina to Liberia to Nigeria, participated in one of the wars feeding the slave trade, led a revolt against white missionaries, and made a life in Nigeria for himself and his descendants, but he did it as an outsider without previous social or genealogical connections in that particular place.

When I told Vaughan’s living descendants in Nigeria and the United States that the lore of the “tribal marks” did not accord with written evidence, many of them were incredulous. Although all of them based their understanding of family history on the article published in Ebony in 1975 (copies of which they all possessed), more than one insisted that their sources were oral while mine were written, and thus theirs were more authentic and direct.

I ended up writing the book about Church Vaughan’s life, to the extent that I could reconstruct it from verifiable sources, and the connections between West Africa and the United States that it reveals even in the absence of his father’s alleged country marks. At the 2018 meeting of the (US) African Studies Association, Atlantic Bonds: A Nineteenth Century Odyssey from America to Africa was awarded the Melville Herskovits prize for the best book published in English that year in any field of African studies. Judges appreciated its comparison of white supremacy in multiple locations as well as its invocation of the memory of the African diaspora—sometimes more imagined than tangible—in different historical moments. But at that same conference, the association’s President, Jean Allman, delivered a powerful address about Melville Herskovits, the association’s founder and first president, for whom the book award was named. Herskovits had worked strenuously both to build the African Studies Association and also to marginalize African and African American scholars from it. Through the efforts of Herskovits and his allies, African studies remained dominated by white scholars through the twentieth century, and they conceptualized Africa as distinct from the African diaspora. Professor Allman’s speech was part of an effort to bring this history back into the memory of Association members.

Who we commemorate, of course, tells us how we want to be now. At this past fall’s African Studies Association conference, I participated in a roundtable considering the possibility of renaming the book prize. The panel and the audience speculated about new names that would reflect current, and more widely-held, values. Few there argued—as some in North Carolina do with Silent Sam or Julian Carr—that Melville Herskovits must be understood in the context of his own time, or that we must not forget about his valor. People in my academic field seem to accept that memory undergoes revision over time—as it should. And just days later, as I was reminded after my brain hemorrhage, we understood once again that life is precious and short: one of the participants in that discussion, the brilliant literature professor Tejumola Olaniyan from the University of Wisconsin, died of sudden heart failure.

I have now learned that Amelia was not present when my hairdresser came to my hospital room this past June and gave me the pixie cut. Jonathan and Christian did not visit me in Wilmington at the same time; and anyway, how on earth would I have been walking into my room then when I could not even get out of bed? So the two memories that I think I have of the period before my last week in the hospital—the only two memories of that entire four weeks—are both wrong.

What do I have of that time that I can believe? I have physical changes, including a bulge for the shunt in the back of my head and some cut marks in my abdomen. I need more sleep than I used to. Something is wrong with my sense of taste, because often food seems more like medicine than like whatever it is. I’m still a little wobbly on my feet, although that is getting better.

I have the gifts people sent me: a fuzzy blanket, socks, a sweater (people knew how cold I was), books, plants. People also sent lots of food and flowers, but I only have the cards left that came with them—some of the 126 cards and letters that I keep in the cardboard box.

And I have the historian’s evidence: my hospital files; the letters, journal, and emails; the later recollections of my informants. Historians know that such sources contain their own inaccuracies—just as the 1975 Ebony article did—but we mine them for some kind of truth anyway.

The more my recovery progresses—which it thankfully does—the more even the memories I do have recede. Still, as Luise’s book, last year’s African Studies Association panel, and the recent controversies over Confederate monuments remind us, things are remembered (or forgotten) for important reasons. That’s why Church Vaughan’s descendants wanted to believe that he had returned to the place his father had been captured from. My mother must surely be right that my body does not want me to remember the trauma of my injury and recovery. But one thing Silent Sam’s or Melville Herskovits’s defenders and I have in common—much as I disagree with them otherwise—is that we don’t want to forget, because remembering gives us some sense of control over our identity and perhaps our future.

So what explains the two memories that I think I have? What is their larger truth? Like so many other aspects of “the incident,” it might just be random. But when I think of that haircut, with my friend Leila there and my daughter Amelia imagined to be there, a sense of warm wellbeing settles over me. It’s the same sensation I feel when I go back to that surely invented scene in the hospital room with Christian, Jonathan, and my beloved Matt. It’s the calm confidence that people are with me: that my dear friends and relatives are not leaving me to face tangled hair or bureaucratic paperwork or death alone.

If memory tells us something about who we are, it also tells us about who we are or were with. That is, it reveals human community. The apocryphal story of Church Vaughan finding his father’s people in Africa is about connecting people of the African diaspora who feel a sense of kinship because of shared history.

If memory tells us something about who we are, it also tells us about who we are or were with. That is, it reveals human community.

I do not expect that I will ever remember those lost four weeks in the hospital this past summer. I know what other people say about them and what some of the written evidence tells me, but I will never perceive them the way we perceive our own experiences. But if I cannot recall what it was like to suffer a brain hemorrhage, to struggle against mortality and machinery in the ICU, or to gradually relearn walking and talking, what I do know is that my human safety net was there. Through countless acts of physical and emotional support, and by reflecting back to me a version of myself that I could recognize, my family, friends, and colleagues helped me recover who I am. Matt, Amelia, and many others made it into my consciousness and kept me tethered to the living world.

Lisa A. Lindsay is Bowman and Gordon Gray Distinguished Term Professor and chair of the department of history at UNC-Chapel Hill. A specialist in the history of Nigeria, the slave trade, and the Atlantic world, she is the author of Atlantic Bonds: A Nineteenth-Century Odyssey from America to Africa (UNC Press, 2017).