“Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art” was co-curated by Trevor Schoonmaker (Nasher Museum of Art) and Miranda Lash (Speed Art Museum). Before the show opened in September, we sat down with Schoonmaker and artists Stacy Lynn Waddell and Jeff Whetstone, both featured in the exhibition.

“We have no idea what it truly means to be southern”

Stacy Lynn Waddell: I am very interested in the necessity of a show like this and what brought all this to bear for you and Miranda [Lash].

Trevor Schoonmaker: Miranda and I started talking about it about five years ago, and I started thinking about it, in earnest, when I moved from New York back to North Carolina. So, ten years ago, but not in any serious way, just moving from the center of the U.S. art world—contemporary art world—to Durham, North Carolina, and [asking] what does that mean, how can you be an active participant in Durham? But also thinking, “What does it mean to be southern?”

I think at the show’s heart there’s an attempt to complicate the notion of what it means to be “southern.” As you guys know, as well or better than I do, [it’s] generally perpetuated as this monolithic, sort of, singular voice as if there’s only one southern culture when it’s this very multi-faceted place. That’s the crux of why we wanted to first tackle it. But why do it in a contemporary art exhibition when it’s been done so well [in] documentary studies, literature, music, film, so on? [W]e’re three southerners sitting here who participate in the larger national/international discussion, but how hard has it been for us to get a foothold, how hard is it to get recognition in Durham, North Carolina, in the national dialogue? How hard is it for the South to be accepted, mentioned, or recognized? I think trying to unpack the canon a little bit to allow some more room, to create a little bit more room and open it up—I think those are the two major reasons.

Jeff Whetstone: I think as artists, too—and Stacy can attest to that because we’ve talked about this a lot—there’s been very little press about art in our region. As professional artists we read the journals, we want to read about somebody’s show—what did this critic say about this show? [But] it’s very hard to find a consistent voice about art happenings in the South. We kind of had it in The Independent in Durham—there was always a visual arts column—but compared to New York, you know, there’s forty different press outlets about art that come out monthly, so I think that . . . those press outlets help the conversation along, and I think that . . . seems to be missing historically in a way, right?

SLW: I think so. I’m interested in that and also this idea of having to be a journeyman as an artist, especially if you are from here. There are vestiges of that journey sort of narrative in the exhibition. I’m wondering if you thought about that relative to the artist “situation” that chooses to be here—the southern artist that is southern, but also is located and creates a practice here?

TS: [I]f you look at film and literature and music, there [are] all these stories about the southern traveler—people leaving and coming home. It’s part of my story. It’s not everyone’s narrative, but I think it’s a big part—that sense of going out, exploring the world, [and] bringing something back. I think it’s in many ways true everywhere, but it’s part of the lore of the South in some way—part of the mystique—and so we do try to tease that out in the exhibition. You know, there are a lot of themes that we try to get out, and narratives that we try to pull into this show, but I think that [foremost] is thinking about, “What does it mean to be southern?” And the conclusion for us is, of course, we have no idea what it truly means to be southern because we can’t define it, and this [exhibit] is no attempt to say, definitively, “This is what it is.” Actually, rather, the whole point is to complicate that notion.

The South is charged unlike any other region—big region—in America.

JW: It seems like the South is—it’s a contested site, it’s a contested place. I think that if we had to define what it means to be southern, it’s having to deal with the contested nature of the South. I left the South for the first time in my life, more or less, last year, and I find myself in Princeton, New Jersey, as, like, the Every Southern White Male, so people ask me, “So, down in the South . . . ?”

TS: You’re representing. I noticed you’re wearing shoes today. (Laughs)

JW: What do people think I’m like? Every conversation is kind of funny. One thing I do recognize: it’s charged unlike any other region—big region—in America. The exhibition certainly addresses that. How do you . . . both delve into [the South] and also kind of expand on it [without presenting] such a didactic, polemical argument?

TS: I think the way of doing that is by the type of work that you show. The type of work that you two create, for example, is not didactic. There are certain themes and narratives that you continue to mine, but it’s not heavy-handed.

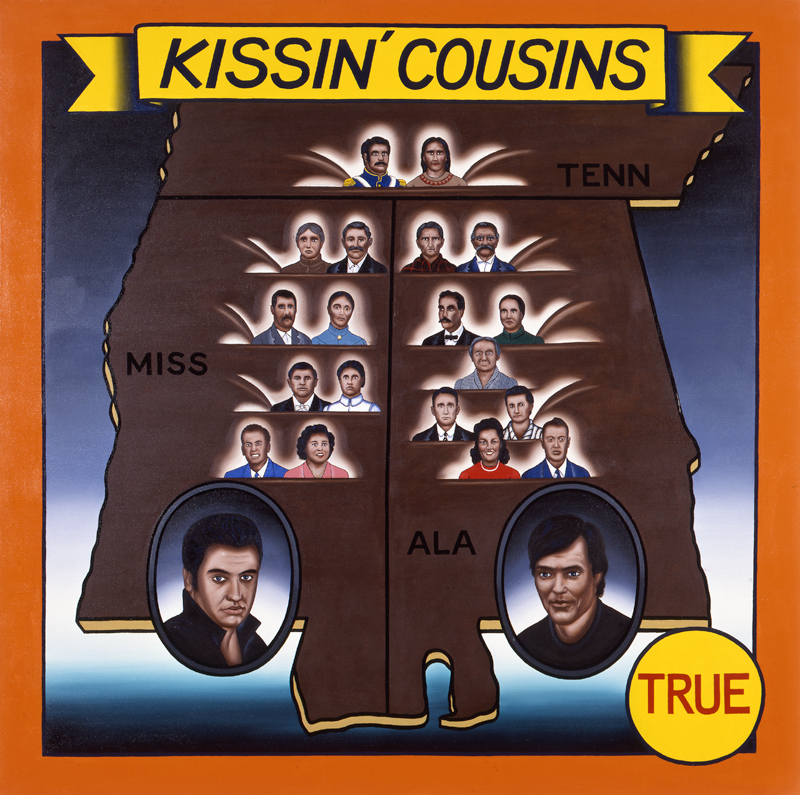

There are so many terrific works that we could have included, but they are so easily read on the surface level. It’s like, “OK, I got it, the South is bad for its racism. Check. Move on.” And that’s not the story we are trying to tell. We know that’s part of what it means to be southern, but it is so much more complex than that. [So we tried] to have a light hand and bring in works that . . . bring in a complexity . . . like, for instance, the Hank Willis Thomas video, Black Righteous Space. It conflates the Confederate flag with red, black and green, the colors of African liberation. Immediately he has brought two diametrically opposed ideologies together in the same space, then he’s layered [them] with the sound of speeches and comedians and musicians, so he has created this space that is clearly pro-Black, but that’s also implicating everyone—in a different way from, but similar to the way Kara Walker sometimes does. The slippery works are the ones that we gravitated towards, simply because the whole thing needs to be unpacked in some way, not to be neatly repacked. I mean, maybe the question for me to you, Stacy, and to you, Jeff: How do you think—or not—your work addresses this tension in the South that Jeff was speaking about?

SLW: I don’t know, because I’m thinking about the work now as part of an exhibition relative to what I was thinking when I made the work and how that piece came about. I think for me, it’s about a sense of beauty and the ephemeral nature of beauty and how it shifts very drastically from person to person. All of that tension, and the “sticky bits” of being in the South, are troublesome, but there are also—there’s a kind of beautiful patina on all of that that we get to kind of see or not see. So that’s what I’m thinking about—probably all the time—but specifically for that piece.

TS: When we first started this project almost five years ago, you were two of the first people I talked with about this show, and both of you mentioned beauty in those early conversations. We talked about it a lot, for good reason. Maybe, Jeff, you could say a little bit more about that.

That beauty balanced with fear makes this kind of Gothic South so powerful.

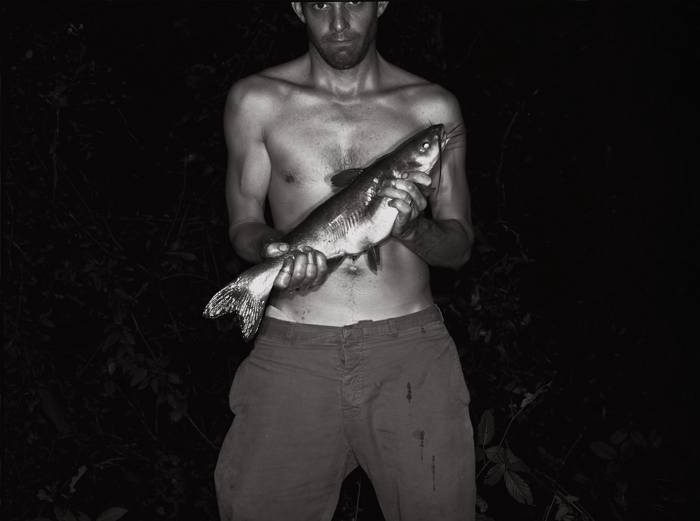

JW: I guess I have to go origin story stuff. I grew up in rural Appalachia, 25 miles out of Chattanooga, Tennessee, a place with babbling brooks and caves and mountains and rock formations and big forests and beauty was just—it wasn’t taken for granted, it was just beautiful. I loved it. But what tainted the beauty, or what made it more interesting than just pastoral beauty, was that all the kids who lived around me were really, really mean. I was scared to death every time I went in the woods. I mean, we were friends, but the Lowry boys and my cousins, it was just this masculine contest in the woods all the time. I never knew when I was going to be put up to these masculine contests of swappin’ licks . . . I was always the loser of that, I was kind of a nerd-naturalist. That beauty balanced with fear makes this kind of Gothic South so powerful. It’s awesome beauty in that you feel awe, and that means you’re humble—you can only feel awe if you are humble—and I was humbled to the men around me, in a way. So it made the beauty spiced with danger, and I think that’s where beauty factors into my work.

SLW: It’s romantic. It’s the American narrative, right? Straight from the nineteenth century. Look at those landscape paintings. That’s everything.

“It’s hard to escape the southern accent”

There’s a very sophisticated conversation in the South that people outside of the South don’t know about.

SLW: [A]s an artist who is southern, who lives in the South, whose practice is rooted here in the South, [and who is] not just making work about the South, I feel a certain kind of way when I look around the room, when I see folks that are not from [this] place; it’s East Coast/West Coast hip-hop, that battle. I’m wondering, trying to get inside your head [about including non-native southerners].

TS: From the most basic position, I think diversity makes everything stronger. So I think a conversation about the South is stronger with voices both from within and from without. Most of [the] voices [in Southern Accent] are from within, but there are a lot of strong voices who are not southerners. Important to note: those artists weren’t commissioned to create works about the South. As you both know, they had been drawn to the South already. The South has been inspiring to them, or troubling for them, or whatever it might be for them to come and produce the work, or think of it, or reimagine it. So that’s the first reason, and I think the second is, going back to the first question you asked: “How do we expand this conversation in the broader contemporary art world and have the South be included?”

Well, we need to include these other voices to take back this conversation. If it’s an insular conversation, then we just keep speaking to ourselves, which is what we do a lot, and is not a bad thing. What it means is that there’s a very sophisticated conversation in the South that people outside of the South don’t know about. I want people to know that this sophisticated conversation is happening and that others have been paying attention from the outside. That’s what Miranda and I were looking at in a nutshell, that’s the basic thinking behind it. But back to beauty for just a moment—I think it is, for almost every artist in the exhibition, a way to draw people in, it’s an accessible thing. Beauty of nature is very hard to compete with, so there is the natural setting, the landscape, of course, to define space, but just beauty in general is a point of entry that makes people linger and look harder and be drawn to it so that then they take the time to start thinking about the more difficult conversations in the work, which both of you do so well. I think that even answers your other question about the tension of some other works that were not included. Some of those are so heavy-handed they lose the beauty or they are too oblique.

“A reason for the making”

TS: What about context for both of your work? Where it’s shown, where the work is seen, and how it is read? Is it read discernibly different in your mind whether it’s in Durham, North Carolina, or New York, or Los Angeles, or abroad? Are there different expectations? How has it played out for you?

SLW: For me, it’s always seen through the black, southern experience. That’s the thing for me. If I could figure out a way to jumble that a little bit so that whenever there is something written about it you [don’t] always have to start with the historical context as being a reason for the making when it isn’t, it just is a part of what’s there. That, I think for me, is a presumptive force field that I’d like to . . .

TS: You’re saying, it’s the presumption that’s the driving force rather than ever-present . . .

SLW: It’s about the black struggle and “Your family surely could be descended back to slaves and you’re making work as this sort of way of pushing past all of that.” Why can’t I be making work like Kiki Smith because I want to be a fairy dancing in the light?

TS: Jeff’s doing that. (Laughs)

SLW: But that’s an interesting thing that you bring up—it’s the ability for certain artists to be able to shape-shift. Jeff is a white, American male from Tennessee, and I’ve talked a lot about his access with his camera.

TS: I thought you were going to say his accent.

SLW: That, too! The fact that there are some spaces that he goes into with that camera that I would think twice about.

JW: I think that comes from living around hyper-masculine southern males and figuring out how to negotiate not getting beat up.

TS: So you went to art school? (Laughs)

JW: I beat up a couple of people at art school. It felt good. (Laughs)

Part of my process [is] this whole, “Hey, y’all. Whatcha doin’? That’s cool! Mind if I take a picture or two?” And pretty soon I’m at the dinner table. I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing, but I capitalize on it quite a bit.

Back to the context part, I think that the glaring difference is when I show my work in the South, my work’s got a sense of humor about it. . . . I had this film that I made of these turkey hunters and this guy was imitating this turkey call. He was imitating a female turkey, luring a male turkey, and he was saying all this dirty, dirty stuff to the male turkeys he’s about to shoot. Southerners think it’s like a comedy, they laugh at all the parts I think are funny. Some people from the other regions just think it’s a rape sequence happening or something very disturbing. And it is both. I wish the humor was a little bit more evident. I almost have to decode the humor. Maybe I’ll include a laugh track, little animals laughing. I think that’s how the work is. I’m not connecting to something that we all can laugh about a little bit. I don’t know if you laugh at my work, or if you think there’s humor. I’m looking over there and you’re like, “Your work is not funny.”

SLW: I never really thought about it as funny. I thought about it as sad, not funny, but maybe it is. A little bit.

JW: A little bit. A hole in a fish. The trope of the fish picture.

SLW: What’s funny about it probably for me is what now has started to become inert in terms of symbols in the South that people are railing against. I’m really interested in this whole conversation about the Confederate flag. You think about people being very upset about the Confederate flag. For me, as a southerner, it holds no power. It’s probably because I am [southern], and we deal in symbols all the time, and I’m a maker of images. I’m not that possessed with angst about [it], but it’s powerful—it’s a powerful symbol.

But what I find that’s funny in your photographs are things that I’m probably more nervous, that I’m thinking less about, like white men in camouflage that do have guns, or on four-wheelers circling the wagons about to go hunt. But they aren’t looking for animals, they are looking for me. Or they are out burning crosses. Those are the things that are so easy for people to go to.

JW: That monolithic idea of white Appalachia: scary, racist.

SLW: That’s why they aren’t laughing, because they are trying to be politically correct about how to think about it. Either you are going to say nothing or you are going to be politically enraged. These people are homophobic; that’s not right. These folks are card-carrying members of the NRA; that’s not right. People don’t know where to go.

JW: [To Trevor] I want to ask you a question. You’ve been planning a show subconsciously for ten years, consciously for five, and now it’s happening [when] we are in this very, very aggressive political, presidential election and everyone is taking one side or the other. [D]o you like this timing of the show?

TS: Impeccable. I’m joking. I think that the timing works in our favor. I hate the reason that it works in our favor, but the big thing for me is that it allows for conversations that are needed. It enables the conversations that need to be had. Art is one way that can help promote dialogue in some ways and in a way that’s not about saying, “My God, one more black person was killed today.” You can have conversations via the works in this show that complicate it. It doesn’t allow the black-and-white reading you were just talking about.

I think the timing . . . makes it that much harder for it to travel outside the South, actually. [I]t could be seen as a regional show, but it’s an American show. These are national issues, and we see that as we walk through the show, but I think that makes it harder for northeastern venues or western venues to say, “Yeah, I’m going to take this,” because of the political climate, even funders. It’s had an effect.

“They are searching for something”

TS: You both deal with the connection with, not so much animals in your work, but the connection between the landscape and humans in history . . .

JW: I facetiously said something about, “Why aren’t there more bugs, insects, reptiles and fish in contemporary art?” It is a good question. They need a stage right now as we find ourselves inching towards the “sixth extinction,” as a lot of biologists call it.

I think that something about the South, I’m sitting here right now totally eaten up with poison ivy. I’ve got poison ivy all over me.

SLW: Didn’t you hug me? (Laughs)

JW: No, it’s not contagious once the oils are gone. I got just chewed up by mosquitos. It’s an endless battle here. If you stay too long somewhere, something is going to crawl around your ankles . . . There’s something about the humility toward nature that you have I think in the South, that I just want to express. I wish it was expressed more . . . [Pieter] Bruegel [the Elder] had it right. He had people subjected to the landscape, and the beauty of that, really right, instead of the landscape as something we should protect.

It’s the landscape, which is a connection to a kind of spiritual life or psychic richness that we embody here in the South.

SLW: It’s the reason people find it hard to break through—there’s that force field around the region. It’s our connection to the natural world. It’s our understanding of it, because it’s about instinct. People who are really good gardeners, it’s an instinct, you can’t learn instinct. Well, maybe you can. It’s hard to google it. The insects, fish, and birds, it’s about our acceptance of that thing that’s larger than we are. I think that [in] other regions in the country, the architecture is larger, or the transit infrastructure, the subway system, that’s larger than we are. The Mets, that’s larger than I am. It’s not that here. It’s the landscape, which is a connection to a kind of spiritual life or psychic richness that we embody here in the South—in our literature, in our music, in our churches on every quarter corner. It’s a part of who we are that is difficult for people to understand or come into. It’s just a difficult thing, the natural world.

JW: When you were talking, I was thinking about my grandmother planting by the signs—plant by the signs of the feet, plant by the signs of the stomach, all these different vegetables she grew planted by the signs—and she was not a religious person. It wasn’t even spiritual to her, it’s how you do it. The phase of the moon, it was how you did it. She never would have read it in a spiritual way, but she was in tune to maybe the forces of physics.

SLW: It’s a John Cage composition. Think about that relative to John Cage. It’s the same thing, it’s a conceptual practice.

It’s interesting to think about the South and modernism and think about Black Mountain College. It’s interesting to think about that a particular moment, folks that helped usher modernism in all came here to North Carolina as a safe haven, really. Many for political reasons came, initially, to start a school and to teach this kind of high-end way of thinking, this kind of clean aesthetic that was about how to live your life as much as [it was] about how to make images. This openness and freedom. It’s interesting to think about these ideas around intellectualism in the Academy and why we don’t find that in the South, why that’s not seen as something that is at the root of who we are, when in fact it is. When people don’t really talk that much about Black Mountain College or when they do, there’s no connection made.

JW: They do in New York, man. Black Mountain, there’s always some kind of article about Black Mountain College mentioned. It’s talked about in New York City a lot more than it’s talked about in North Carolina.

SLW: Which is not surprising, but in a particular way.

JW: I’ve had five people since I’ve moved up there, “Oh, Black Mountain College. Have you ever been? We’ve been thinking about taking the family there.”

SLW: You’re the travel agent, too.

TS: Not much to see.

JW: Yeah, not much to see, and they’re like, “What do you mean? There’s not a museum there?” Yeah, no, there’s not.

SLW: The ideas have permeated all walks of life.

TS: It’s an interesting idea, people leaving London or New York or wherever and setting up a recording studio in a remote area, like Compass Point in the Bahamas, like, “We need to get out of this center, we need to get to some place we see as being more authentic, or there’s a cultural density.” They are searching for something, so they come to the mountains of North Carolina, set up Black Mountain. Go to a remote island in the Bahamas and set up this amazing studio and have the Talking Heads and everybody record there. There’s a searching, and I think it comes back to a people’s impression that there is something more real, more authentic that can be found here. You can get away from the artifice of the big city and strip it all away. In reality, there’s a real density to a lot of the work in the South. Look at the Thornton Dial—it’s like accumulation. So there’s both. There’s never an either/or.

Join us December 15 at the Nasher

for our Winter Issue Launch Party

Join us for “Gaudy or Nice: Southern Cultures Winter Issue Launch Party” at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University this Thursday, December 15. Curator Trevor Schoonmaker will discuss the current exhibit, Southern Accent, with artists Jeff Whetstone and Stacy Lynn Waddell. Selections from Southern Accent and an earlier conversation with Schoonmaker, Whetstone, and Waddell are featured in the Winter 2016 issue (vol. 22, no. 4).

Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art, on view at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC, through January 8, 2017, was co-curated by Trevor Schoonmaker (Nasher Museum of Art) and Miranda Lash (Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky).

Trevor Schoonmaker is the Chief Curator and Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher Curator of Contemporary Art at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

Stacy Lynn Waddell is a nationally recognized and exhibited artist whose work is held in several public and private collections, including the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, the Weatherspoon Art Museum at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, the North Carolina Museum of Art, the Gibbes Museum of Art, and the Studio Museum in Harlem. View more of her work at stacylynnwaddell.com.

Jeff Whetstone is a photographer and Professor of Visual Arts at Princeton University. A native of Chattanooga, Tennessee, he photographs and writes about the relationship between humans and their environment.