This Bike is a Pipe Bomb rattled the basement windows of our rental house. High frequencies slipped through masonry cracks into the Athens, Georgia night, as amps fritzed from shorting wires. Guitar strings curled from frontman Rymodee’s tuning pegs like rooster sickle feathers. He stood stiff when he sang, a slight figure whose mutton chops grew coiled as a scouring pad. He often hid his bright, kind eyes beneath a worn fedora tilted low, and wrapped his rawboned body in a denim vest. A shoddy microphone pressed to his lips, his voice reverberated against the plumbing and floor framing that crisscrossed overhead.

“This is what I want, black kids and white kids, sharing all the songs / that their grandmama taught them,” he screamed in a manner that honored both his love of English anarchists and his Tuscaloosa bloodline. This 2002 plea from the Pensacola, Florida trio found power in a room full of sweaty young punks. Alone, we were weirdos; together, we demanded sing-a-longs. A few crumpled dollar bills bought anyone entry.

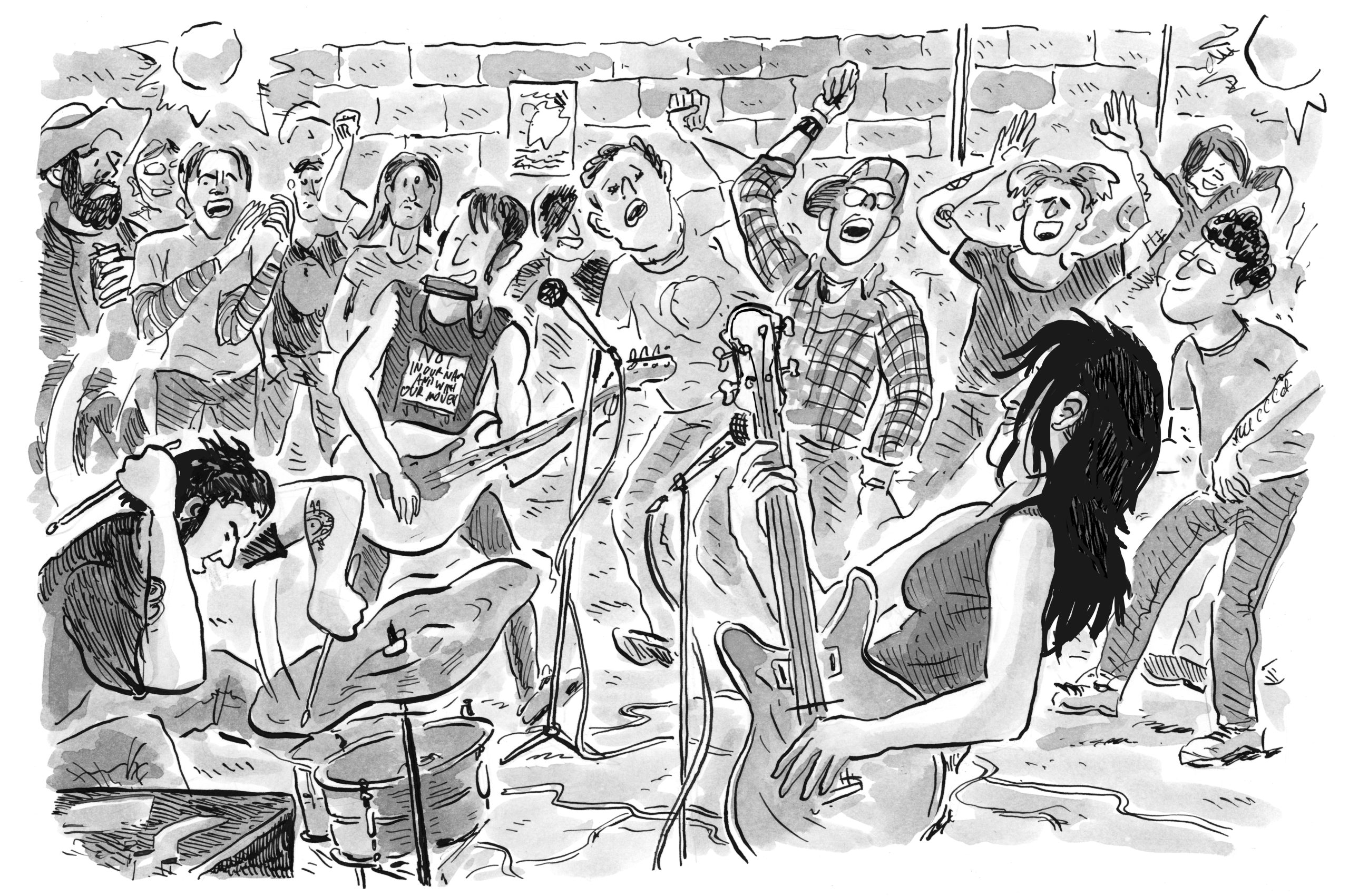

The crowd squeezed the band vise-tight, bumping bassist Terry Johnson and Rymodee into Ted Helmick’s drumset, which fell away from his foot mid-thump, cymbals spilling onto the dirt floor. Precision didn’t matter. We looked forward to the broken strings and miscues that paused songs, when Rymodee’s nervous chatter and Terry’s ribbing found voice. Most of us loved their music, a sound not quite punk or country (they couldn’t pull off either with grace). The Pipe Bomb were the proud and discordant offspring of twang and protest, and the songs raced from choruses to outros with messages of social justice and folk teachings. Even metalheads flocked to their awkward hoedowns, seeking a safe space where beer spilled on clothes was quickly forgiven as the result of a good time.

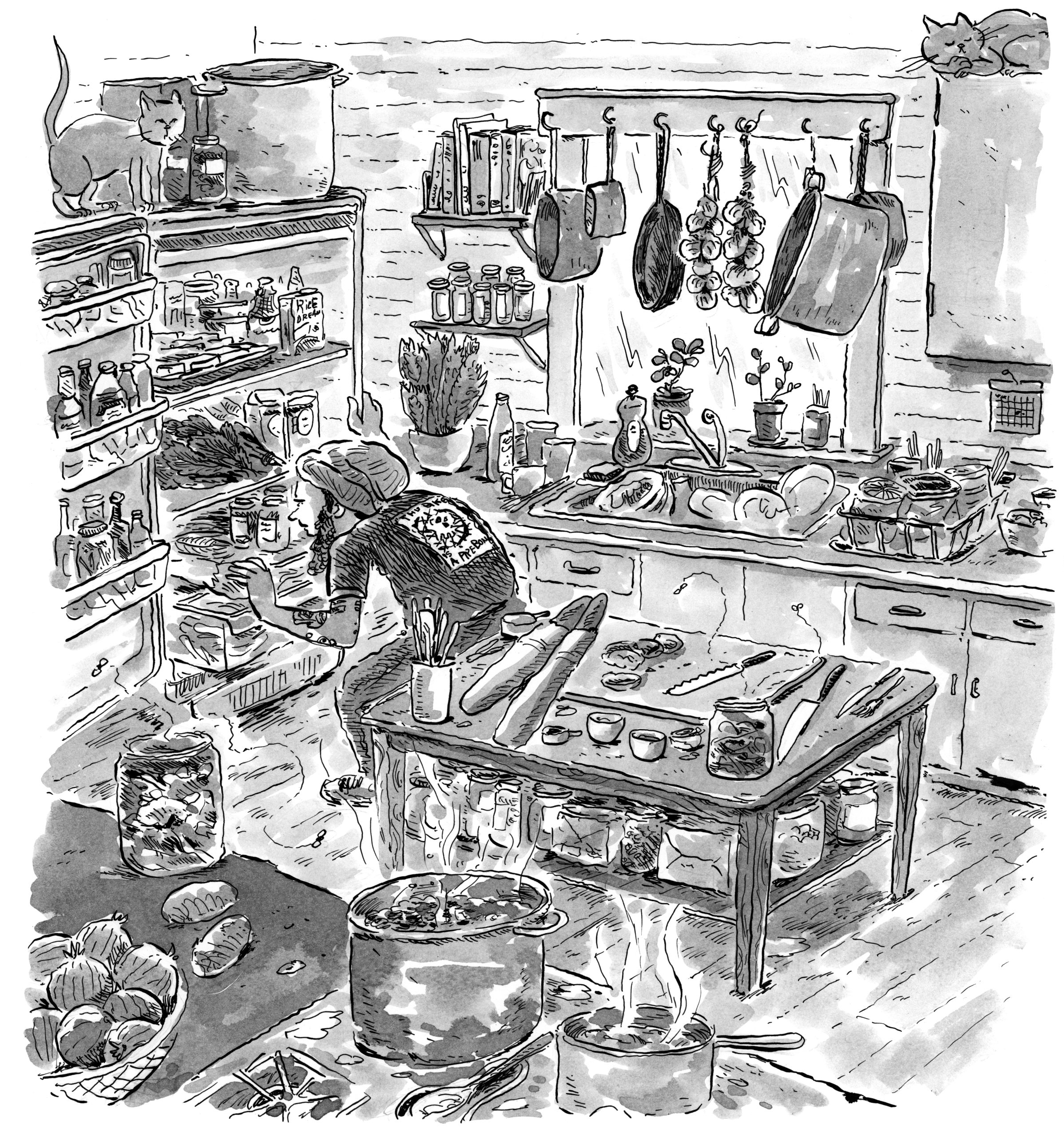

In the basement, nothing demarcated fan from musician. That continued when Pipe Bomb shows ended. Amps put away, a second performance began. Crates of cookware emerged from deep within the band’s Jenga-stacked van. Rymodee unloaded his suitcase of spices. The party would move to the kitchen.

Residents of our house shared demographics with punks in other cities: almost exclusively white, we were the disgruntled, latch-key progeny of broken homes, naïveté dashed by hanging chads and an invasion in Iraq, working in dish pits to afford shared bedrooms. Our politics—not yet fully formed—leaned radical. Youthful and absolutely sure we were right about everything, there was one thing we regularly got wrong: we sucked as cooks.

Survival depended on devouring the unsold pizzas from the restaurants that stoked us with minimum wages. At best, we could prepare gelatinous stews that sat in our stomachs all day like rain-soaked blankets. We downed spoonfuls while holding our noses.

After the shows, I rode along in the Pipe Bomb’s van, sitting on a speaker cabinet, on the hunt for free food. They scoped out dumpsters behind grocery stores for unblemished produce—and they invariably scored. Flashlights illuminating garbage bags, we unearthed boxes of eyed potatoes and flats of blotted squash from underneath leaking bags. To complete the pantry, they walked in the front door and purchased missing ingredients with donations they’d accepted during their sets.

Back at our house, Rymodee quartered potatoes for roasting. We helped by boiling beans in big pots, and chopping collards for stewing. Rymodee ditched recipes. He set the oven for roasting and browned onions. We noted the temperature and technique. Like an alchemist, he used nutritional yeast—a golden brown powder packed with vitamin B-13 and umami flavors—to make gravies and cheese sauces devoid of dairy and lard. The Pipe Bomb drew power for this magic-making from cast iron skillets, totems we’d only heard of in grandmotherly lore. Terry demonstrated how to season and clean the pan, Rymodee coached on cornbread, and Teddy hoovered up the crumbles. Nothing represented the lessons we took from the band better than cast iron. The pans symbolized permanence: heirlooms for kids whose familial links were thinning out. Cast iron topped the last Christmas wish lists we’d write for our parents.

Cast iron topped the last Christmas wish lists we’d write for our parents.

We piled plates high from the buffet and collected ourselves on the porch. Brunch sessions began with coffee, then veered into day-drinking. We knew to call out from work when the Pipe Bomb came to town. The next day promised a wicked hangover, maybe leftovers. This was slow food for broke folks, and the afternoons stretched on. Rymodee strummed tunes on a weathered acoustic guitar, humming melodies from the International Workers of the World’s Little Red Songbook and whatever he remembered from the power chords played by last night’s opening band. Teddy retreated to tweak the van motor. Terry filled us in on the news from other southern punk scenes, like what new bands had formed in Gainesville with ex-members of so-and-so, why the kids who lived in the famed Pink House of Asheville had been evicted, and who we might expect to arrive in town by boxcar next week. But conversation never veered too far away from food. She reported on killer tofu banh mis in Fort Smith, Arkansas, and the vegan soft serve ice cream in Fort Worth, Texas, as if she’d just returned from Mars. In turn, we memorized restaurant coordinates in case we ever wound up in the vicinity.

Without fail, the band members cleaned up after themselves. First by pouring the potlikker over roast potato cracklins and wolfing down the leftovers, then by gripping a scrubbing pad like a battle flag and charging headlong into dirty dishes. Soon, after hugs, they were gone. Off to the next city, with a movable feast tucked in among amplifiers and handmade merchandise.

The Joy of Cooking

Rymodee never cooked as a kid. He hung out with his mom in the kitchen to preserve space between him and the living room, where his Navy officer father watched football. He admired his mom’s work on the stove but gleaned little. He remembers she once let him stir a soup.

At nineteen, Rymodee joined the Air Force. In exchange for a G.I. Bill to pay for college, in 1989 Uncle Sam sent him to Grand Forks, North Dakota. A job as base fireman allocated plenty of idle time. On a pawnshop guitar, he plucked C majors while digesting the “three squares” miscues posing as chow each day. Listless in his bunk, he tired of forcing junk food into his body and questioned the need to eat meat. He petitioned to cook for himself. Higher ups demanded medical assurances that if Airman Ryan Modee skipped the efficient nutrition of the mess hall, he’d maintain a level of health fit to serve. A doctor approved. Request granted.

One hiccup: Rymodee’s new diet leapfrogged his abilities. He’d only tended pots someone else had filled, and nobody on base could help him. Military knife skills didn’t translate in the kitchen, and enlisted men cared little for measuring scant teaspoons. From a slim selection of thrift store cookbooks, he found a classic, an early edition of Irma S. Rombauer’s The Joy of Cooking. Its frayed edges resembled his mother’s copy and the straightforward directions helped him skip or replace meat with ease. The book was useful, but it had one fault: Irma’s mashed potatoes didn’t taste like Mom’s. He told his bunkmate he needed to call his momma and find out how she made those mashed potatoes.

Rymodee had never been close to his parents, especially his father, his mother only by default, and when he reached for the phone, the handset felt glued to its base. But he had to know. Her fix was simple: “Oh, baby, I just put sour cream in them,” she said.

After two years in Grand Forks, Rymodee returned to Pensacola. There’d be no G.I. Bill–funded matriculation. Instead, insurgent pursuits filled his days. He edited a zine, produced on a found typewriter, called “The Bike Punk Chronicles,” about alternative transportation and dumpster diving. As he told a fanzine interviewer in 1995, the zine captured his disgust with “technology and smog and smoke, and computers, and modems, and fax machines.”

They rode bikes like they were invincible, smoked cheap rolled cigarettes, chased away sleep, rode freight trains for kicks, and drank rotgut. Living long lives seemed contradictory to their actions. Eternity was never the point.

A growing number of Rymodee’s punk friends adopted vegetarianism. Some stepped further, toward veganism. The decision was more a rebuke of commercialism than health-based: they rode bikes like they were invincible, smoked cheap rolled cigarettes, chased away sleep, rode freight trains for kicks, and drank rotgut. Living long lives seemed contradictory to their actions. Eternity was never the point. Instead, meat-free meals were a middle finger to a culture stuffed on burgers, an act of nonviolent protest. Eating discarded food doubled down on that conviction. They turned capitalist waste into abundance.

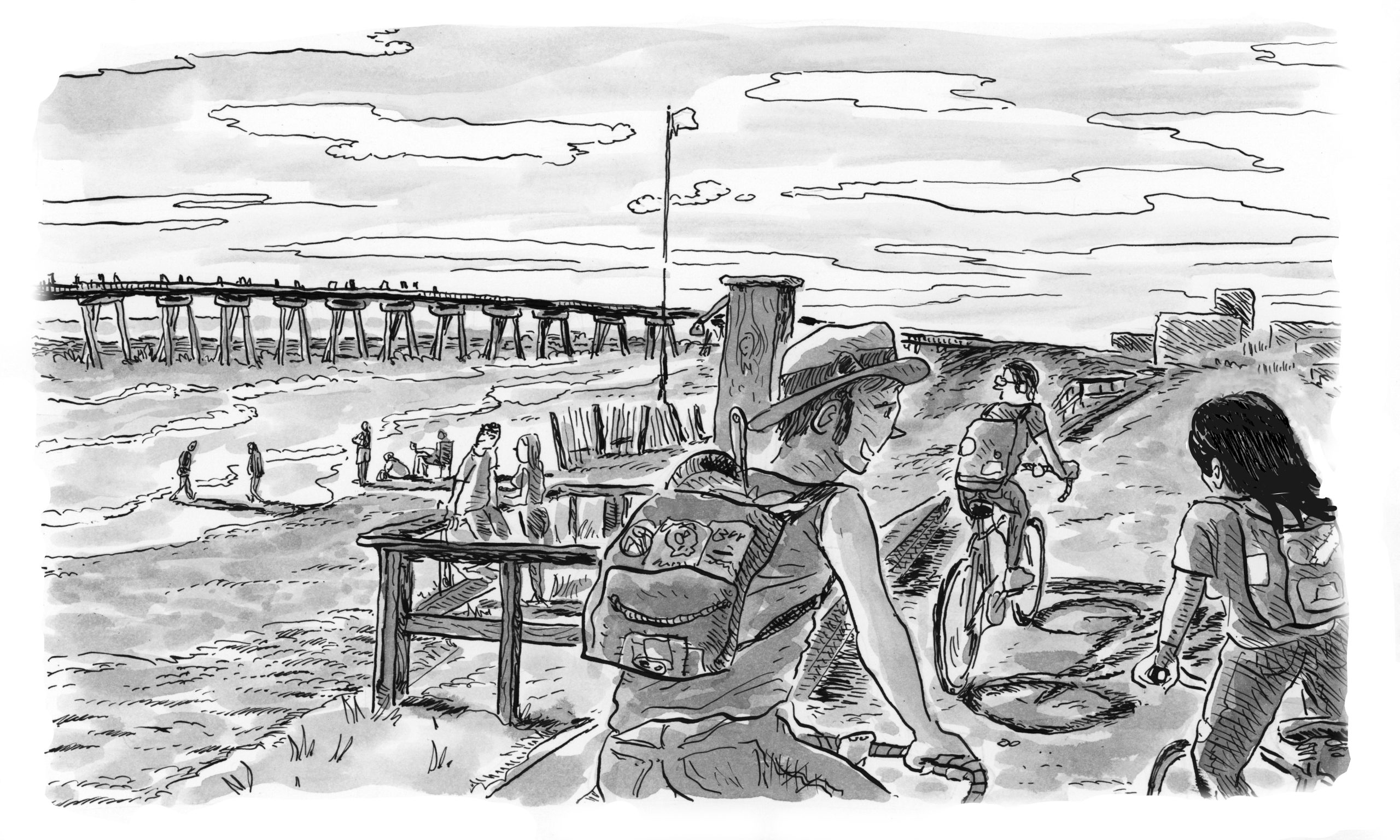

Backpacks full of cookware, carrot tops flaring out like bushy tails, Rymodee and friends biked through balmy Pensacola until daybreak set the city’s alabaster beaches ablaze. Few people witnessed this punk peloton, but that did little to quell their passion.

A Moveable Feast

The first iteration of This Bike is a Pipe Bomb in the early 1990s mixed Rymodee’s folky songs with a friend’s Devo-esque rhythms. The pairing was short lived. The name was a nod to Woody Guthrie’s weaponized guitar and evoked images of populist transport and armed rebellion. The sound had to match, and New Wave just didn’t have the bite.

Drummers entered and exited as Terry, the owner of a punk club and diner called Sluggo’s, learned bass and became a reliable partner. Pushing forty, she was a decade older than her bandmates. Terry had a smile that tendrils of mahogany-dyed hair couldn’t hide, and her ardor balanced Rymodee’s shyness. Teddy, a tinkerer with a chin-strap beard and a patience for stuck lug nuts, joined full-time in 1998.

Soon after, in Sluggo’s attic, the Pipe Bomb recorded its first full-length record. Rymodee sang about civil rights heroes who “never made it home alive” from Selma, the war in Kosovo as a brand new Vietnam, and how he desired to fight alongside the Black Panther Party whenever it was ready for a scrawny white boy to join up.

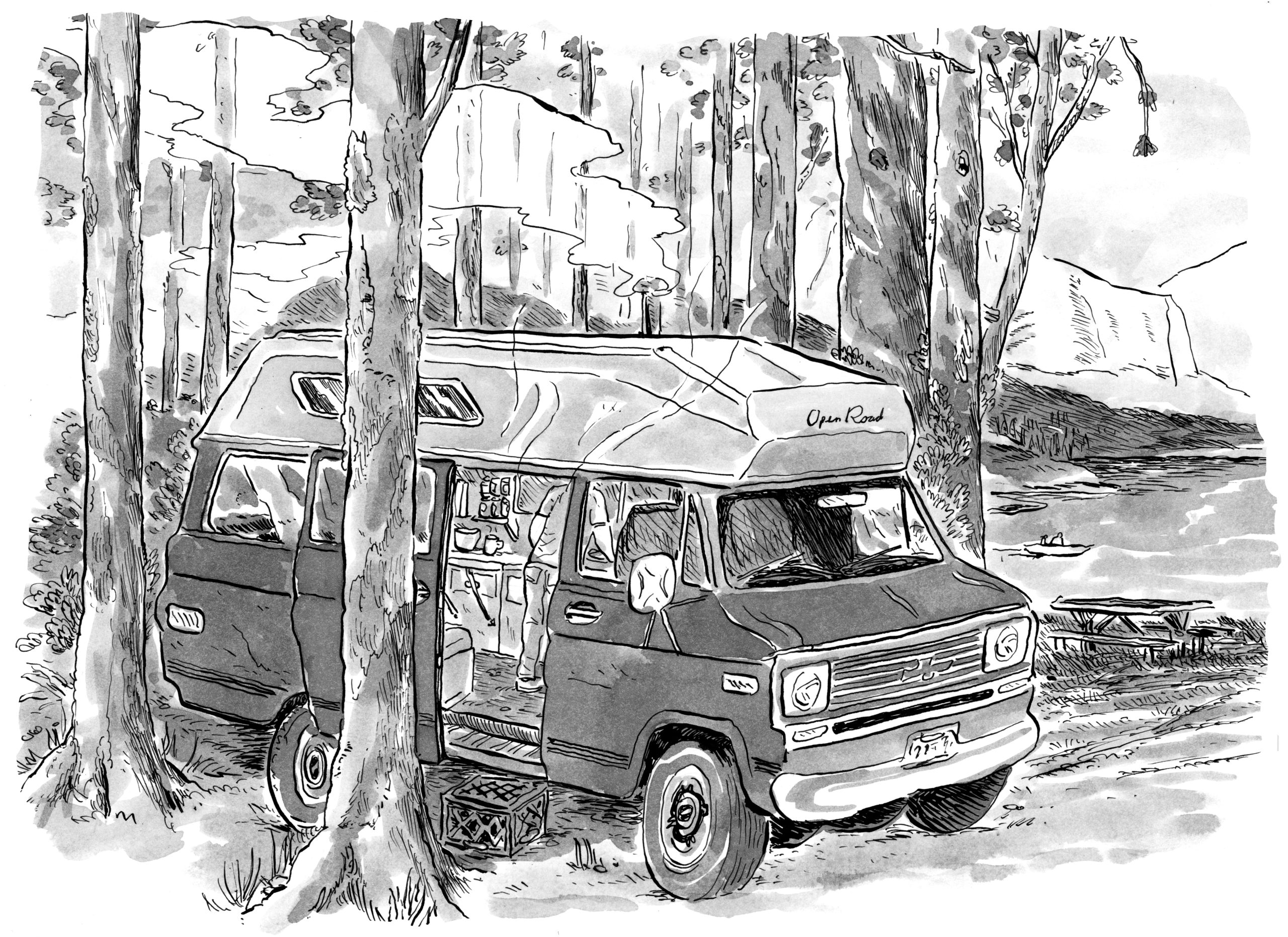

The Pipe Bomb then set out on tour in a Chevy Open Road, an early model mobile home replete with kitchen. Terry baked cakes as they drove. Between distant gigs, they stopped in state parks and cooked lavish meals of fried tofu and collard greens. Teddy wouldn’t ask if Terry and Rymodee were hungry, just if they were ready to eat again.

Between distant gigs, they stopped in state parks and cooked lavish meals of fried tofu and collard greens.

Their traveling larder confused the state patrol. One officer pulled the band over and searched the van’s spice collection for narcotics. He held up a bag of nutritional yeast flakes, and grilled Rymodee on its contents. Just seasoning, sir, Rymodee told the wary officer.

Meals were more likely than cops to keep the Pipe Bomb running behind on tour. Lunch proved more important than punctuality, as if the point of the tour was dining, not promoting records. They were three people who loved to eat, and, luckily, also enjoyed playing music together. So if the Pipe Bomb stayed behind in Birmingham to bake fresh biscuits, we couldn’t fault them. It was their nature.

Drinking Schaefer Light and crunching empties under our boots, my roommates and I often waited for the band on our porch, hardly catching a buzz, sinking deeper into couches that humidity had encased in a veneer of mold. Our ears pricked up at the rumble of approaching cars, like expectant children waiting for their parents to return home from work. When they arrived, the night unfolded as so many before, a blend of buffet and bender. Anecdotes about their itinerant lives were filled with what seemed like never-ending fun. That life seemed unattainable—until, one day, they asked our band to come along.

Saving Their Own Community For Last

Touring bands acted as emissaries of early 2000s punk culture. In vans came unwashed youths from Little Rock, Arkansas, to remote outposts like Starksville, Mississippi, or to my own city of Athens, Georgia. Roadies saddled with crates of vinyl set up merch tables peddling 7-inch records from their scene. They sold singles from bands that saved for months for a day in a studio, and might never do so again. One yawp for posterity, then done.

The Pipe Bomb offered more than that. And my band, Carrie Nations, hoped to follow suit. For thirteen days on the road, we trailed the Pipe Bomb like elephant calves. More than giving us a practical education in how to be a band, the Pipe Bomb introduced us to the rebels and wingnuts hidden throughout the South, a more feral and peculiar place than we could’ve imagined. We met a fierce crew of anarchists in Asheville, North Carolina. The resource center they operated housed an anti-capitalist newspaper and an organization that sent books and personal letters to prison inmates. We met envoys from off-the-grid queer communities in the mountains. Despite the seriousness of their daily rigors, or perhaps because of it, our new comrades could lose themselves in dance for a night. In an old New Orleans furniture warehouse-turned-artist’s commune, our bands played on old fat floor beams that bowed under our janky rhythms. Before the show, we served soup to the homeless. Afterwards, we lounged in a backyard garden, exotic plants stretching toward the moon, and watched a film projected on the building’s aluminum wall.

More than giving us a practical education in how to be a band, the Pipe Bomb introduced us to the rebels and wingnuts hidden throughout the South, a more feral and peculiar place than we could’ve imagined.

These and so many other punk hostels would succumb to the pressures of the housing market and blasts from hurricanes. Few survived the Bush presidency. Far worse, by the end of Obama’s final term, holdouts like the Ghost Ship in Oakland, California, became graveyards of smoke and ash. But in 2002, these spaces flourished, even in the South. They proved life at the margins could satisfy both belly and mind.

The Pipe Bomb saved its own community for the last stop on tour. Rymodee and his then-girlfriend Jen regularly hosted travelers long-term. They were ambassadors for a city that few, outside of the military, knew much about. Instead of remittances from the road, the Pipe Bomb sent back punk kids decked in old denim and duck canvas. Longing to inhale the same Gulf breeze that had sustained their favorite band, they hitchhiked to the Panhandle to pop tents in backyards. Arriving in Pensacola, the possibilities we collected for our own lives—the soup kitchens, guerilla gardens, and junk bike hospitals—overwhelmed us. Bodies splayed out in chairs on their porch, photocopied zines drooping from hands, we’d digest it all and draw up plans between naps.

Jen and Rymodee spent free time in the kitchen when they weren’t busy at Jen’s vegan restaurant, the End of the Line. Their fridge overflowed with leafy greens, sleeves of bread, and trays of tofu. Flies buzzed around a mason jar full of compost. Well-loved pots hung from hooks in the window trim. A light film of dust on the counter countered the burnished perfection of Jen’s classic appliances. She cherished her heirloom baby blue gas stove so much that she’d tattooed its image on her shoulder. As Florida weather rarely required sleeves, the homage was always on display.

In their living room, Rymodee cared for a menagerie of anachronistic instruments. Out of materials culled from trash piles, he reconstructed a folk orchestra, replete with hammer dulcimer, singing saw, and a stand-up bass. Jen and their friends joined Rymodee to form a house band, the Tube Smugglers. They recorded murder ballads and shanties about cast iron care and cannibalizing yuppies. Rymodee’s musical gizmos held starring roles. Naturally, Rymodee had drawn a fanzine of blueprints to replicate his Frankensteins and a few days at his house allowed for plenty of time to dabble with his creations. If punk was about opting out of capitalism, making our own instruments felt like the pinnacle.

That point could be taken further: we didn’t need bars or clubs. For our first gig in Pensacola, we even refused a roof. On a spring evening, once dusk fully settled and afforded a little cover, musicians and fans lugged amplifiers, microphone stands, drum sets, and a generator down the CSX rail line that split Pensacola Bay and Bayou Texar. We slipped off the tracks onto Hobo Beach, a slim stretch of white sand interrupted by driftwood obstacles. Under a tree canopy, we arranged a stage and attacked our instruments. Bay winds pushed back against our vibrations, muting our noise. Nobody else could hear us, but that was by design. Punks chose vacant spaces on purpose, inhabited bubbles outside the cast of streetlights. The solitude was fleeting. Our hubris urged us back into the glow, flitting at high-watt bulbs like city moths, either clueless or careless.

A decade later, the Pipe Bomb would break up. Terry invested deeper in Sluggo’s. She doubled down on her diet by offering only vegan options and opened a second location in a blue-collar section of Chattanooga, where she moved with her boyfriend. In a few years, yoga studios, crossfit gyms, and specialty grocers would engulf the restaurant. She country-fried wheat gluten steaks as global brands encroached.

Rymodee and Teddy scattered to San Francisco, where, with a Whole Foods on every corner, urban development incorporated healthy living. Teddy opened a bar. Rymodee landed a job at a long-running food co-op. He worked in the stockrooms and the freezers, where he learned the business motivations for dropping decent food into dumpsters.

Thousands of miles apart, the trio remained counterculture fugitives as authenticity and community became corporate mantras. They grew older and shed recklessness and found the future they aged into wasn’t exactly what they’d hoped for. More people cared about what they ate, which is what Rymodee always wanted, but the interest seemed superficial. Waistlines and image mattered more than animal welfare or farmworkers, and that was a bummer.

“You’ve wanted [a better world] to exist forever, and then it happens, and it’s not how you wanted it,” Rymodee said. “Like, if R. J. Reynolds controlled legal weed.” But, for a slew of nights in the early 2000s, Rymodee and the Pipe Bomb preached simple truths about living nourished lives in the narrows and assembled a utopia from cast-offs. They compiled a network of fellow travelers with excellent manners and kitchen chops, who placed food and community above all else. We couldn’t know that, in a few years, the ideals they espoused would stare back at us from the glossy pages of magazines and in the curated storefronts of lifestyle outfitters. The hideouts where dirty kids collectivized kitchen work and scheduled punk ragers would be renovated as condos and “makerspaces,” our DIY ethos run through the spin cycle and marked up well out of reach.

This essay first appeared in the Summer 2018 issue (vol. 24, no. 2).

André Gallant is a journalist based in Athens, Georgia. He teaches at the University of Georgia Grady College of Journalism and publishes Crop Stories, a literary journal critically exploring agriculture in the South. Learn more at www.andre-gallant.com.