This feature is part of a series collaboration with the “50 for 50” project, an initiative of the North Carolina Arts Council in celebration of their 50th anniversary.

Debra Austin was nine years old when her first ballet instructor told her she didn’t have talent. Seven years later, she became the first African American woman invited to join the famed New York City Ballet. Austin toured the world with the company before moving to Switzerland to join the Zurich Ballet, and made history again when she joined the Philadelphia-based Pennsylvania Ballet in 1982, becoming the first African American female principal dancer in a major American company.

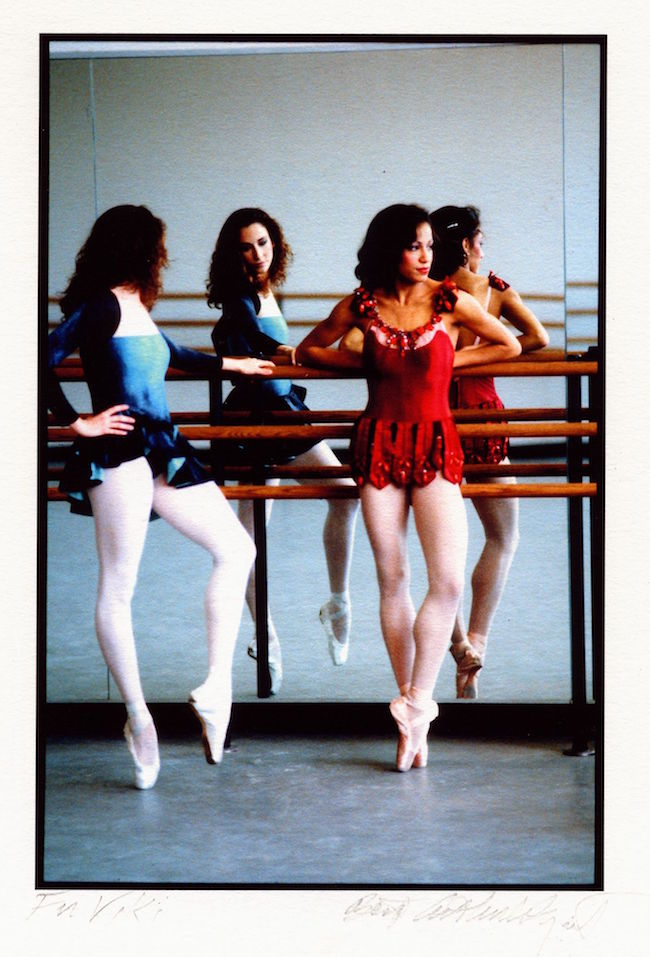

Today, Austin is a ballet mistress at Carolina Ballet, where she works with Robert “Ricky” Weiss, her former artistic director at the Pennsylvania Ballet.

I began dancing when I was nine. I went to a local ballet school next door to me. The teacher there was a Rockette from the Radio City Music Hall, and she told my parents [that] I had no talent. My parents said, “Well, if she has no talent, we’re going to take her somewhere else. She’s 9-years-old, for God’s sake.” So they took me to Christine Neubert’s Academy of Dance, a studio in Carnegie Hall. My teacher [there] was Barbara Walczak, who was a soloist in the New York City Ballet, so from the time I was nine, I had really good training.

When I was 11, Barbara Walzack lured Diana Adams—who was the director of the School of American Ballet—to come and see me because she thought she’d done enough for me. Adams . . . said I needed to work on my feet, which is funny because I don’t really have bad feet, but she said, “We’ll take her on full scholarship when she’s 12.”

When you go to the School of American Ballet, you have to go to a professional children’s school, and you have to pay for that, too. So I was really lucky because I got a full ride balletically, and half a ride education-wise. If it wasn’t for the Ford Foundation scholarship, I don’t know whether I’d [have] been given that opportunity. My parents definitely would not have been able to afford to send me to the School of American Ballet. I was really very fortunate. I did have talent, I guess.

Well, if she has no talent, we’re going to take her somewhere else. She’s 9-years-old, for God’s sake.

The minute I started doing it, it just became something I really wanted to do. It was thrilling. Performing is such a gift. I knew when I was 10-years-old that this is where I want to be, this is where I want to go, and this is my dream.

I got into the New York City Ballet [when I was 16]. Mr. Balanchine came into class and watched the class. [After he left I remember] they went and told two girls that Balanchine had taken them into the company, and they came to me and said, “We need your mother to call us.” I was like, “Oh no, what does that mean? They didn’t take me? What are they going to tell me?” Arthur Mitchell had just started [the] Dance Theatre of Harlem, and I was really scared they were going to say, “I think you need to go to the Dance Theatre of Harlem.” At that time we didn’t have cell phones, and we used dimes—believe it or not—to make phone calls. So I put my dime in the machine, I call my mother at work, and I say, “Mom, you have to call this school immediately. I want to know what’s going on. I’m so scared.” She called the school, and I called her back. She said, “Debbie! Balanchine is taking you into the company.”

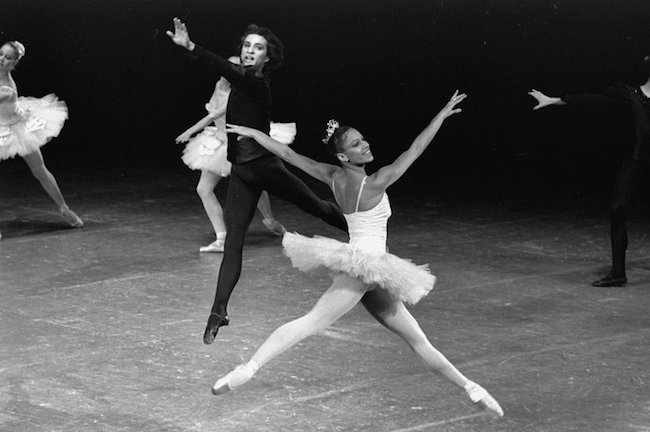

I never became a soloist there, but I danced soloist parts. I did dance a lot of principal parts in the New York City Ballet, and George Balanchine choreographed a solo for me. I have my signature solo in a ballet called Ballo Della Regina.

I knew when I was 10-years-old that this is where I want to be, this is where I want to go, and this is my dream.

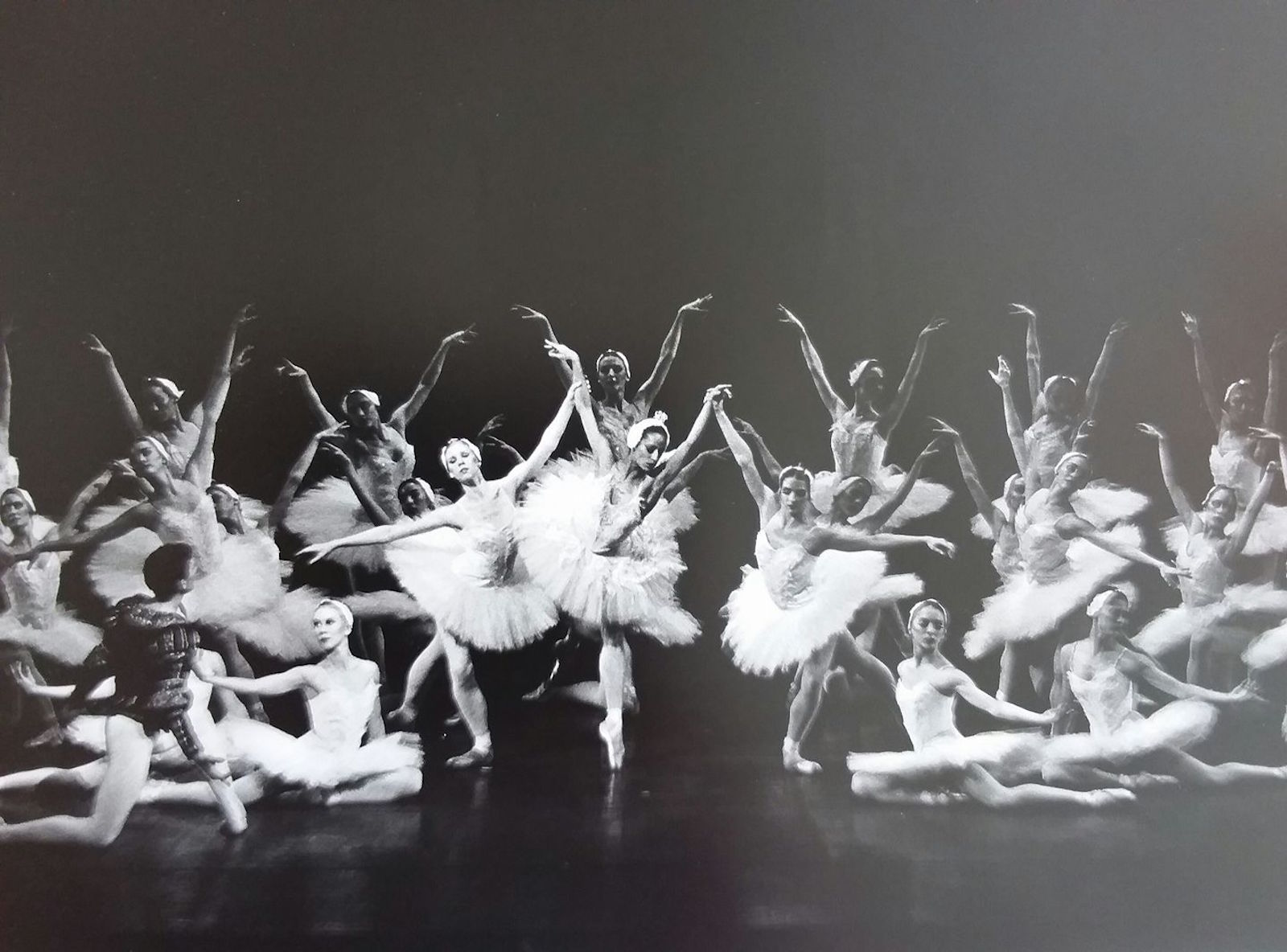

It’s always been a struggle. I just think some people believe if you have a darker skin person out there amongst a lot of “white swans” [they] don’t blend in as well . . . that they don’t fit in. But I think it was much harder in the ’50s. There was a dancer, Raven Wilkinson, they made her pancake herself white. She was not allowed to tell anyone she was black because she was fair skinned, so I think times have changed a lot since the ’50s, thank goodness.

Ricky, who is director of Carolina Ballet, was my director in Pennsylvania Ballet. There is a really funny story. We did La Sylphide, and the person who was staging it said, “I don’t really see her as a sylph.” And Ricky went, “Why?” and she said, “Well, I’ve just never seen a black sylph before.” And he goes, “Have you ever seen a sylph before?”

So there you have it. It’s just what people perceive. The sylph is literally a white butterfly. Was that person saying something because they didn’t believe there would be a black sylph? Or just you know . . . I don’t see that happening in my vision?’ But Ricky was colorblind. I was fortunate.

I’m most proud of doing the full-length ballets [and] being given the opportunity to dance the role of La Sylphide or Giselle, which were never danced by black dancers before. I’ve been doing this my whole life, and I’m thrilled that I was given that opportunity because I don’t know what else I would have done. I’ve been fortunate enough to still work in dance, and my husband works in dance, so for two people to get jobs in the same place in a community that’s not New York City or Chicago is just a miracle.

I just think some people believe if you have a darker skin person out there amongst a lot of “white swans” [they] don’t blend in as well.

Without paintings, without music, without dance . . . what kind of society could we be?

The arts bring so much love and so much education. When you take away the arts, you’re taking away so much education for children. It’s funny. Sometimes I teach at local ballet schools, and I’ll see one of my [former] students [all] grown up at the ballet. They become our future audience.