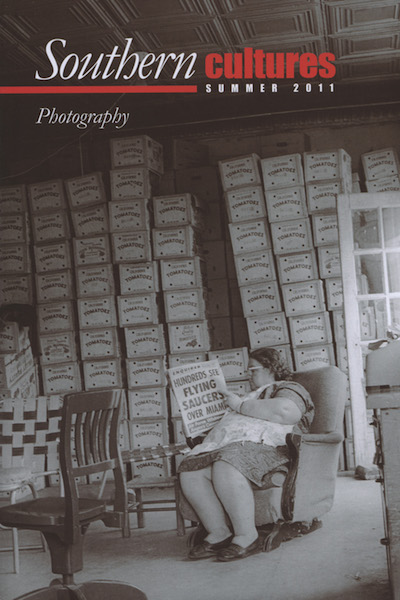

Honoring William Christenberry (1936–2016)

Bill Christenberry was like a spiritual brother who explored his homeland in Hale County, Alabama, with a keen eye. Each summer he returned to document and photograph these familiar worlds. With his meticulous eye, he showed the weight of time on this landscape, tracking change as paint faded and peeled on abandoned homes, churches, and road signs.

Christenberry’s photographs are elegant, precise windows that stand as iconic portraits of our region. His art confronts both the beauty and violence of rural southern scenes, and he deeply believed his role as an artist required that he address the American South with open, honest portraits of its people and places, including the nightmare of Ku Klux Klansmen. His body of work, with its steady, unflinching gaze, allows us to understand the South and our complex relation to it more deeply. Bill Christenberry made the American South a far better place than he found it. His was a life well spent, and I was blessed to have known him.

—William R. Ferris, Chapel Hill, NC, November 30, 2016

William Christenberry, William Eggleston, and Walker Evans have defined southern photography just as profoundly as Cleanth Brooks, Robert Penn Warren, and C. Vann Woodward shaped southern literature and history. Both groups are bound by their deep love for the American South and by their admiration for one another’s work—an admiration that I share. Walker Evans first introduced me to Bill Christenberry’s work in 1973, shortly after he and Bill had traveled together to Hale County, Alabama. I met Bill not long after that trip, and we have been close friends ever since.

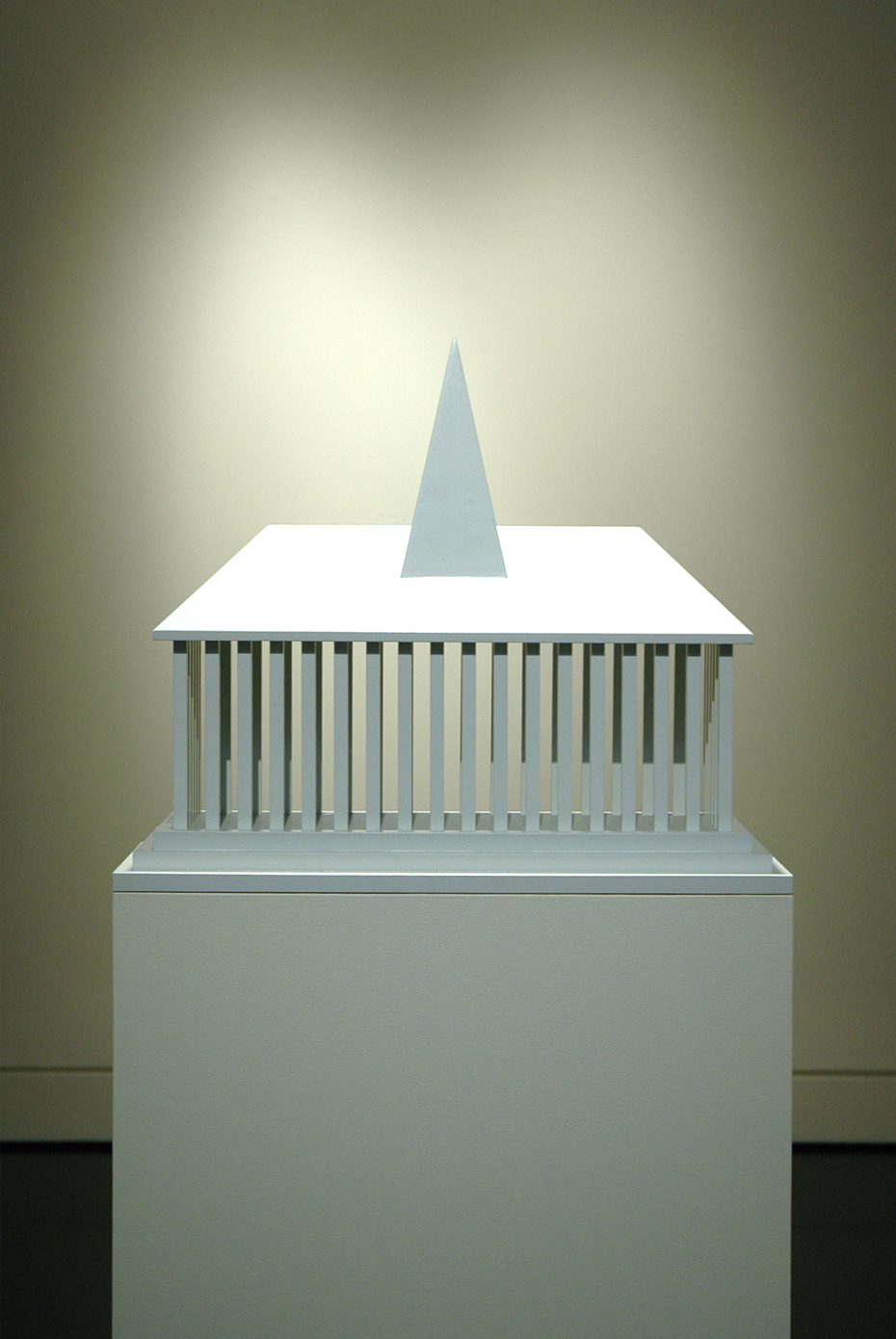

Our understanding of sense of place and how it shapes southerners is significantly deepened by Bill Christenberry’s vision for his work. His desire to “possess” dog-trot houses, country stores, and churches in Hale County first led him to photograph, then build miniature sculptures of these buildings. Once completed, he placed each building on a base of red clay soil that he brought from Alabama. While these buildings evoke pastoral memories of the rural South, Christenberry is not afraid to challenge romantic notions about his home region, as he strives to “[deal] with what I see as both the beautiful aspects of where I’m from and also . . . the ugly or dark aspects.” Calling his Ku Klux Klan series “the most difficult to express,” he summons the terror of Klan violence in tableaus that reveal “a strange and secret brutality.”

Our understanding of sense of place and how it shapes southerners is significantly deepened by Bill Christenberry’s vision for his work.

Bill Christenberry is nurtured by his Hale County roots and has drawn on them throughout his teaching career at the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington, D.C., where he has worked since 1968. Just as William Faulkner created the mythic Yoknapatawpha County to frame his literary legacy, Christenberry draws on his own “little postage stamp of native soil” in Hale County as inspiration for his photography, painting, and sculpture.

This interview was recorded and filmed during the summer of 1983 at Bill Christenberry’s studio in Washington, D.C., as part of my film Painting in the South. The film accompanied an exhibit, “Painting in the South: 1564–1980,” organized by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia.

William Christenberry, In His Own Words

My interest in photography comes out of a background in painting. As a student at the University of Alabama in the mid to late 1950s, I began to look around West Central Alabama (the part of Alabama that I’m from) and see things that I wanted to try to paint, but I didn’t know how to go about it. Santa Claus had brought me and my sister a small Brownie camera in the late 1940s, and I just loaded it with color film and went out to that Alabama landscape and began to photograph what caught my eye, especially rural architecture and graveyards in the country. Back in the studio, those little color snapshots were references for paintings that were quite expressionistic—a lot of gesture and rich surface quality, but with subject matter.

I first met Bill Eggleston in 1962, when I moved to Memphis. I think his interest in photography increased my interest in photography, because I continued to make those little snapshots for a number of years. As I said, they were references for paintings. I never thought of them as art or as serious photographs until later, when I met Walker Evans in New York and he asked to see some of the little snapshots. But that didn’t change the way I looked at things or what I looked at. Then, when I moved to Washington, D.C. in 1968, Walter Hopps [Director of the Corcoran Gallery, 1967–72] encouraged me to begin exhibiting the little snapshots.

Photography for me is a wonderful means of expression, but it is not the only thing that I try to do as an artist. It’s just part of it, along with drawing and sculpture, and although this does not include painting since at least 1968, I don’t doubt that someday I might like to try painting again. But photography is just a part of a total means of expression that crosses over between several means.

Southern writing, and southern literature, has had a greater influence on my work than the work of other visual artists.

Southern writing, and southern literature, has had a greater influence on my work than the work of other visual artists. I don’t doubt or deny that other visual artists have played a big part in what I do. In more recent years Walker Percy, along with other people and their work, has had a profound influence on what I try to express in my work. I don’t know if it’s possible to do visually what they are doing with the written work, but I feel very strongly that it’s worth a challenge. That’s what it’s all about for me.

“Caught up in that one particular place”

I’ve often wondered if I would be doing the kind of work I’m doing if I lived where I grew up, in Alabama, because I find that being 900 miles away in Washington gives me a perspective on home—almost a sense of mystery—that I really enjoy. I find it very difficult to work in other places. It takes me a while to get adjusted to a landscape other than Alabama’s, even when I come into Mississippi, which is not really different from Alabama. But if I go to California, or even in Washington [D.C.], I don’t make photographs. I never quite understood that about myself. I guess I’m just sort of caught up in that one particular place in Alabama, and when I come home on a trip in the summer, I can’t wait to go out in the country. I’m so charged up after being all those months in Washington. And yet I look at Bill Eggleston, who lives in Memphis and makes his forays and pictures down there, and I respect that. I’m not saying that if I lived in Alabama I couldn’t do it; I just wonder about it.

But, you see, I left the South, or the Deep South, because I felt there were opportunities for my sculpture that I didn’t have there: exhibitions and possibly sales. I never looked at it like I might get rich or anything like that, but there was no opportunity. As a photographer—and I’ve experienced this myself—one reason my photographs are better known than my sculpture is that it’s so much easier to get photographs around. You can mail them off, send them to Japan if you have to, and it won’t cost an arm and a leg like a sculpture or even a painting.

I like the sense of distance and mystery that generates feelings by living outside of the Deep South.

I miss living in the Deep South a lot. I have such an attachment to it and such a deep feeling about it, but it’s how you respond to it—how you respond to what you are about. I like the sense of distance and mystery that generates feelings by living outside of the Deep South.

“A strange and secret brutality”

I have done some work dealing with what I see as both the beautiful aspects of where I’m from and also what I consider the ugly or dark aspects. I began work in the early ’60s dealing with the Ku Klux Klan, and that work has been pretty much done through drawing and sculpture—a drawing in three-dimensional expression—and not a great deal of my work on the Klan has been done through photography, at least not yet. There’s a fascination with evil—the Klan work is an attempt to express something about evil, and whether or not it is successful in visual terms depends on whether the viewer responds to it in the way I would like for it to be responded to. I attempt to reveal what we might call a strange and secret brutality, the Ku Klux Klan. I’ve often said that the Klan work is the most difficult to express, because in the work that I have made dealing with the nature of the costumes, the colors have a pretty quality to them. In fact, their satin costumes and bright colors allow for a certain kind of eerie beauty to take place. You have to see the totality of the work before you can really understand what I’m trying to say. It’s not easy to talk about, but it’s an ongoing body of work that comprises over two hundred pieces now that I’ve been putting together since about 1961.

The Klan is a part of something that I’ve known all of my life, or at least heard about. I never actually saw a Klansman until 1961, in Alabama, but in the mid-Sixties they came out of cover, and I saw a lot of them. I fully realize as an artist it is very difficult, if not impossible, to deal with such loaded political and social subject matter, but I feel it’s something I had to try to do whether I was successful or not. I hold the position that an artist should be involved with the times in which they live and try to deal with the things that are good as well as bad. I’ve had many people tell me that an artist shouldn’t be involved with the subject matter of art, but I argue it should be dealt with, as well as a lot of other things. The Klan work was never exhibited until last fall [1981 at the Menil Collection] in Houston, and from what I know of the response, the public is very much in support of what I am trying to do. There were a few dissenting voices, but by and large they were very supportive of the effort.

“I saw all of them in a dream”

Often times I build things that are a result of dreams.

In 1971, during Christmas time, I photographed a certain country church in Alabama. The church by its very nature was small, but the lens of the little Brownie camera and where I was standing made the image seem quite small. I kept that little snapshot with me until 1974, when one night I mentioned to a friend at the studio that I had this real desire to possess this quiet church, but that I knew it was impossible to bring the real church back to Washington. I had this idea that maybe I should like to build a small version of it, but I said, “I don’t know if it’s worth my while; it will probably be a waste of time since I’ve never done anything like this.” But he looked at me and said, “You’ll never know until you try.” Well, I went to work based on that little photograph, the actual church, and a thumbnail drawing of the rear of the church, and I spent one whole year building it. There would be moments of real frustration or near-depression in that year, and other days there would be moments of excitement, like This might make sense after all. Then when the year was out and it was completed, I sat it on a field of real Alabama red dirt that I brought to Washington. Then it seemed to make some sense, some visual sense.

Now I’ve built eleven structures that are based on literal Alabama country stores or churches or other country sites I see. There is considerable interest around the country, and even abroad, in artists who have been influenced or affected by architecture. I’m not the only one, but my pieces have a very narrative or literal quality to them—I won’t deny that. They usually have come from real, existing landscape, but I also make buildings that deal with my childhood memories. Often times I build things that are a result of dreams. I really value what can come in dreams—I just wish they would come more often. I built several buildings—actually four—that are called “dream buildings.” I saw all of them in a dream about 1979; they all vary in color, but the size is the same. I enjoy working this way because it satisfies two needs: one, I have to build the structure, and then after it is built I have to paint it to look weather-beaten. Painting is at least fifty percent of the task, because sometimes it’s not very easy to make something look old when you’ve just built it. But I feel very good about the direction that my work has taken me in the last ten or twelve years, and needless to say there are endless subjects for future building constructions.

“There is always something to look at”

I think it’s harder for me to say why I choose the subject matter I do for my photographs than it is for my sculpture. With the sculpture, the photograph has already been made, and I study it—no, study isn’t the right word. I have it around. I live with it for months, sometimes years, and sooner or later it occurs to me that it wouldn’t make a bad sculpture. For me, it’s more than a response to something in the landscape, more than going out to make pictures of a certain object. That’s one reason why it’s not easy for me to work in terms of an essay, although I’m beginning to learn that I can do that, I can be given a specific subject. For example, I was approached several years ago about the Ku Klux Klan idea, and my initial response to that invitation was, Can I work that way? I can’t say I went into the project with doubts; I just knew it was different. But after I got into it—and I think this is also true of being out on the landscape—as you get into it, moving, looking, responding, something happens.

I’m fascinated by rural graveyards, where people will make the most wonderful objects out of necessity. If they can’t afford to buy elaborate flower decorations, they will make things, in this case out of egg cartons: stitch them together, cut them with sheers, make a Styrofoam egg carton look like a rose bush, or make a Styrofoam cross stitched together. What people do out of necessity is wonderful folk art. I’m intrigued by that. But as far as setting out to look for a specific subject, every time I’ve done that I have felt somewhat inhibited. I just let it come naturally. It just catches your eye.

I can’t say why a certain object appeals to me more than the other. It’s just there, and I don’t think of it as, Hey, that would make a good color photograph. In my case I never really made anything but color photographs. I just started making snapshots, and they were always in color.

“I’m very much in love with where I’m from”

I feel that I’m very much in love with where I’m from—Alabama, the Deep South—and up to this point there has not been a lack of subjects when I’m out in the country. There is always something to look at, even if it’s not in the country. And if it’s not anything specific like a building, a grave, there is the landscape—now that’s what I call the pure landscape, just the sky and the earth—and that intrigues me to no end.

As Alabama changes, I see fewer and fewer of the objects that had attracted me a year ago. They are gone, so I’m hoping that I see something that excites me visually. And often times it has to do with something that nature, Man, or a combination of those two have altered, have shaped, have worked, have left in a different way than what it was before. I don’t dwell on the Civil War or the past. I just seem to be attracted to things that are decaying, that are rapidly vanishing from the landscape down this way in the South. I can’t say I’m obsessively attracted, but honestly I find beauty in things that are old and changing, like we all are changing. I don’t find them ugly. I certainly don’t think I’m making a picture of a “decaying South” or anything like that. I find some old things more beautiful than the new, and I continue to seek those places out, and I go back to them every year until sooner or later they are gone. They have blown away, burned, or fallen down, or just simply disappeared.

Unless otherwise noted, artworks by William Christenberry, courtesy of Hemphill Fine Arts.

William R. Ferris is the Joel R. Williamson Eminent Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Senior Associate Director of its Center for the Study of the American South. The former chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Ferris has conducted thousands of interviews with musicians, directed 15 documentary films, and written or edited 10 books, including the massive Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (1989), which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Les Voix du Mississippi (2013), the French translation of his book Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues (2009), received the “Coup de Coeur de l’Académie Charles Cros Musiques du Monde” prize in the world music category. His most recent book is The South in Color: A Visual Journal (2016).