"I looked at the glistening beauty of the bluegill scales, looked at my catfish, looked at Bobby. After careful comparison, I told him I wanted the catfish, that it was my first, that it was bigger, that I had caught it. We should keep what we caught, I explained. That was the right decision."

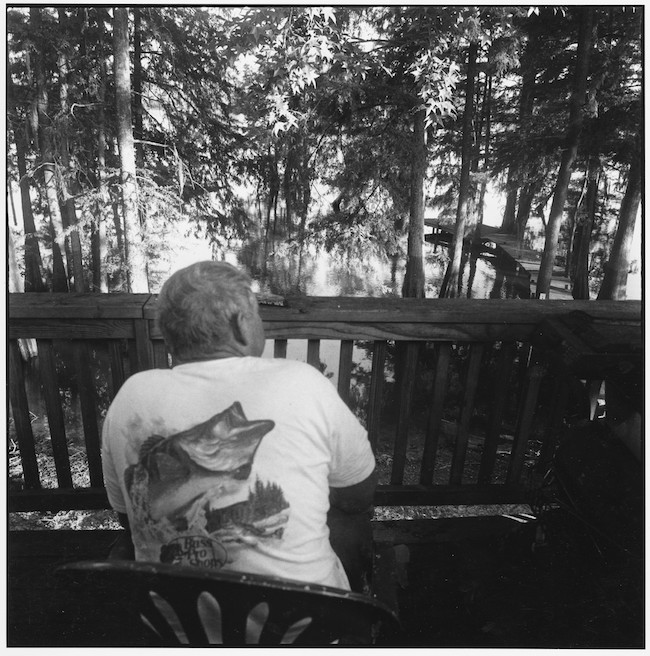

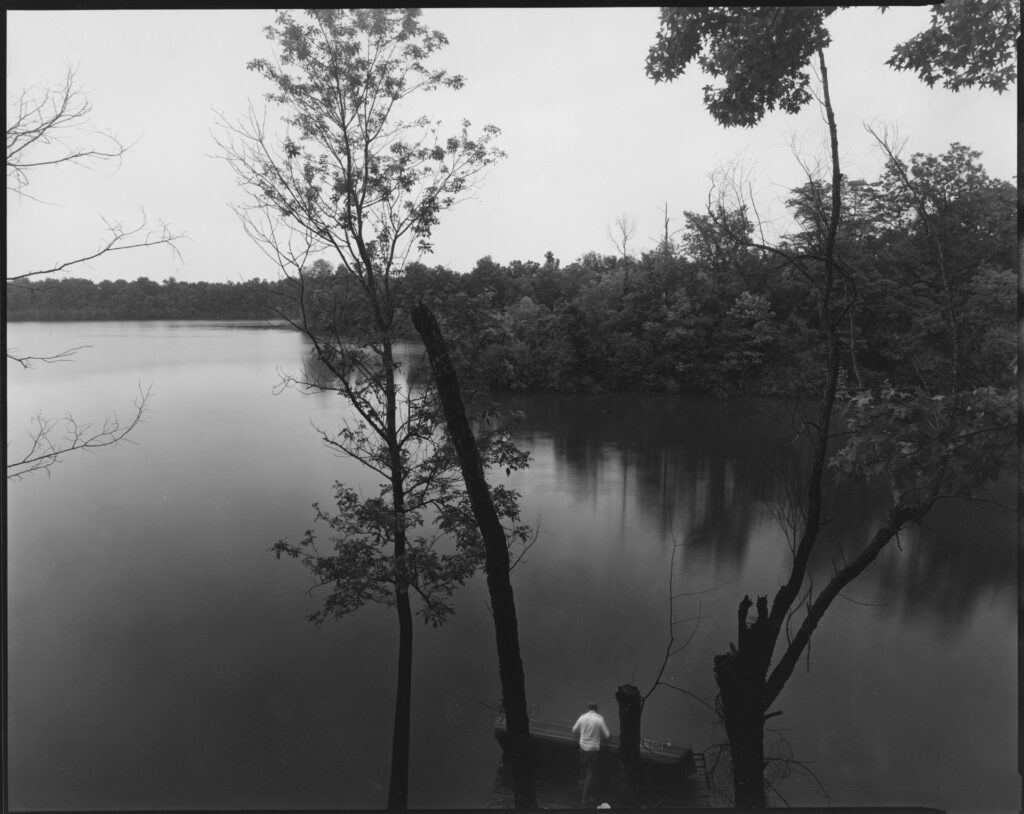

I was in second grade in Kentucky when my friend Bobby invited me to spend Friday night with him and go fish a farm pond the next morning. His father, a long haul truck driver, was off work for the weekend and drove us some thirty miles out of town where we baited simple bream hooks with red worms and carefully watched our white and red bobbers, in youthful hope of success. I have no recollection of how long we fished, how long we anticipated fish action, how big or small the pond was. My only clear memory is that I caught a channel catfish from a place midway on the pond dam. And then at some other time in the morning, Bobby caught a hand-sized bluegill.

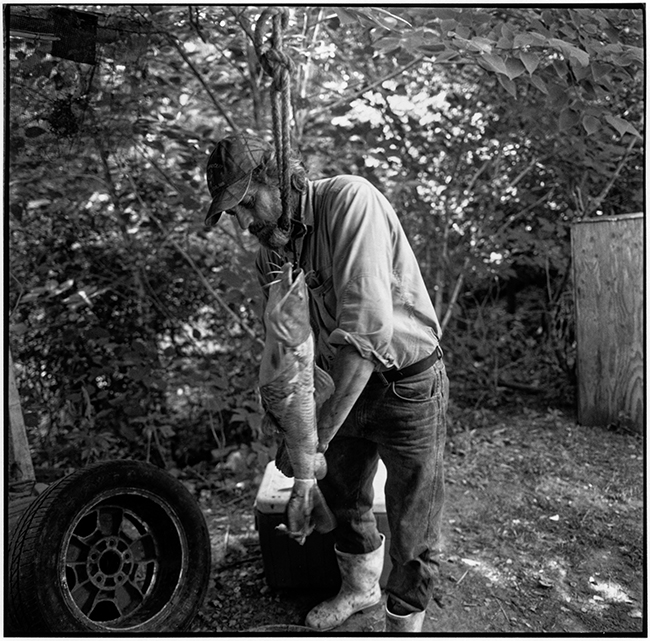

This was my not my first fish, but it was my first catfish. I had never had someone carefully explain to me—as Bobby’s father did that morning—how to remove a catfish from a hook without getting stuck by the spines on the side of the fish. Just as he was helping me remove the fish from the hook and thread it onto the stringer, Bobby approached me with his freshly caught bluegill. “I’ll trade you this bluegill for your catfish,” he offered. I looked at the glistening beauty of the bluegill scales, looked at my catfish, looked at Bobby. After careful comparison, I told him I wanted the catfish, that it was my first, that it was bigger, that I had caught it. We should keep what we caught, I explained. That was the right decision.

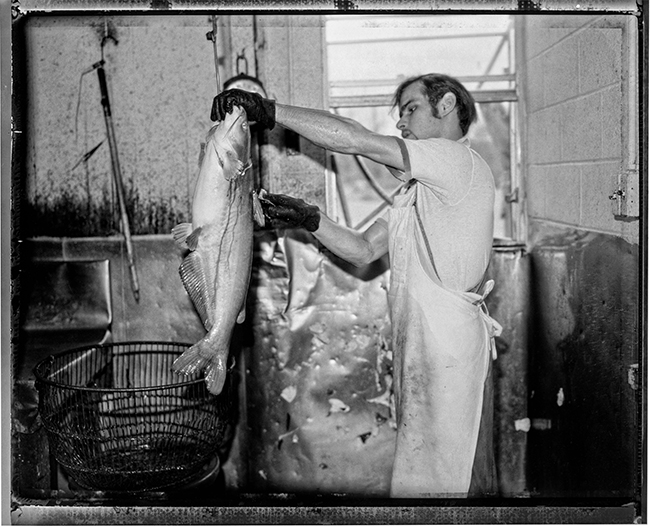

By the time I arrived home with that lone catfish, not overly big, but bigger than any fish I’d caught before, I was completely enchanted with the idea of my catch. I filled a galvanized tub with water, slowly introduced the fish to new water, and then called for my family to come see what I believed a kind of miracle. Always knowing I would eventually eat the channel cat, I left him to swim in the tub all night, waiting to learn to skin, clean, and cook him first thing in the morning; my first fried catfish the centerpiece of a magical breakfast, a culinary celebration.

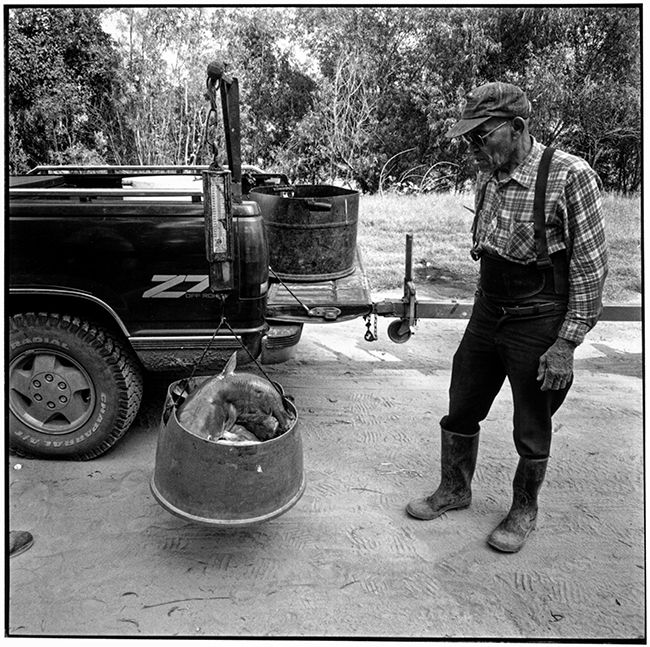

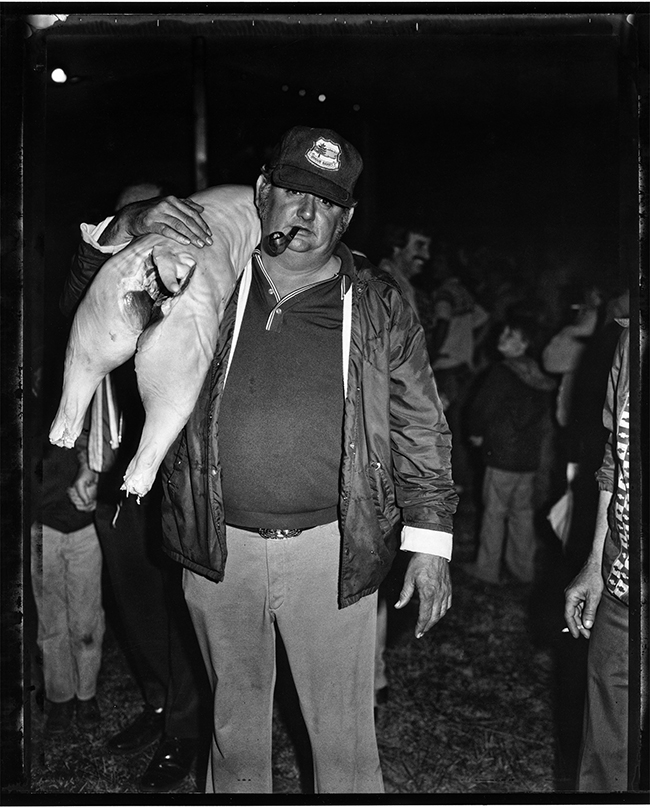

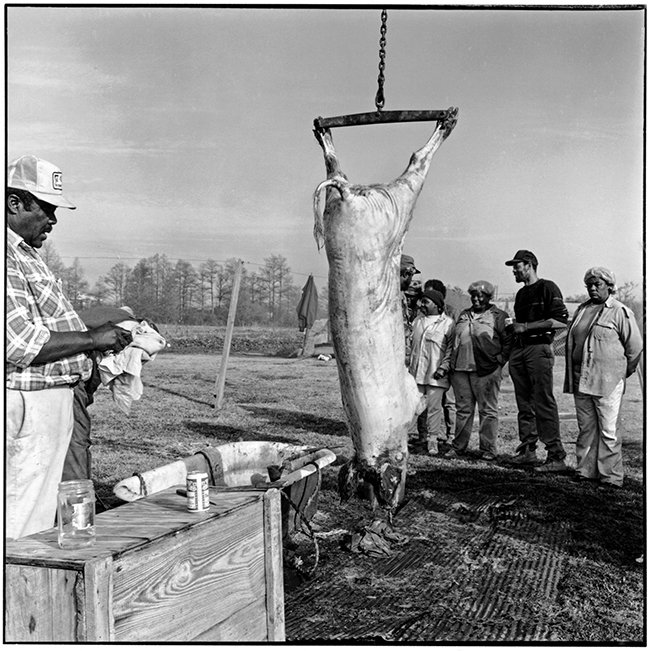

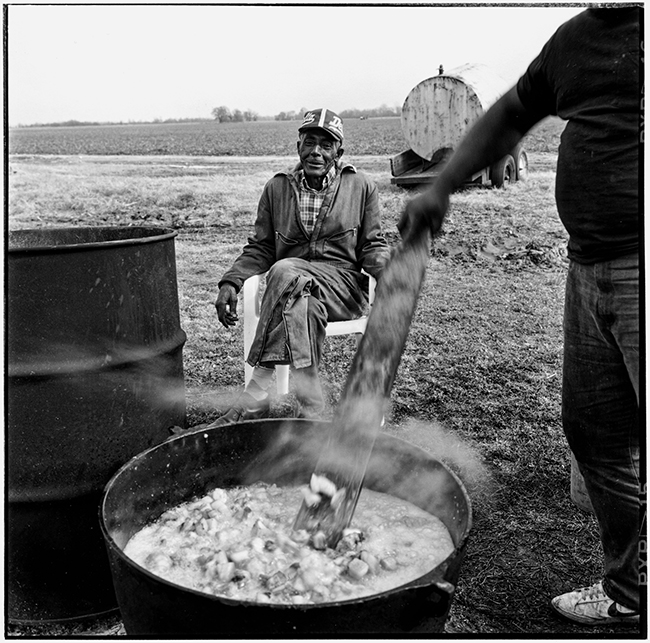

“A significant part of the pleasure of eating,” writes Wendell Berry, “is one’s accurate consciousness of the lives and the world from which food comes.”1 Food we gather for ourselves, food we process ourselves, food that calls us to engage in the work and wonder of sustenance matters so much more than mere food consumption. We cannot and do not have to be the catcher of all we consume, but the deeper our involvement in the origin of our meals the more fully we feel connected to place, to water, to the confluence of tributaries that bring what feeds and matters, to our own small presence in the world, to what we eat for pleasure and what we eat to endure.

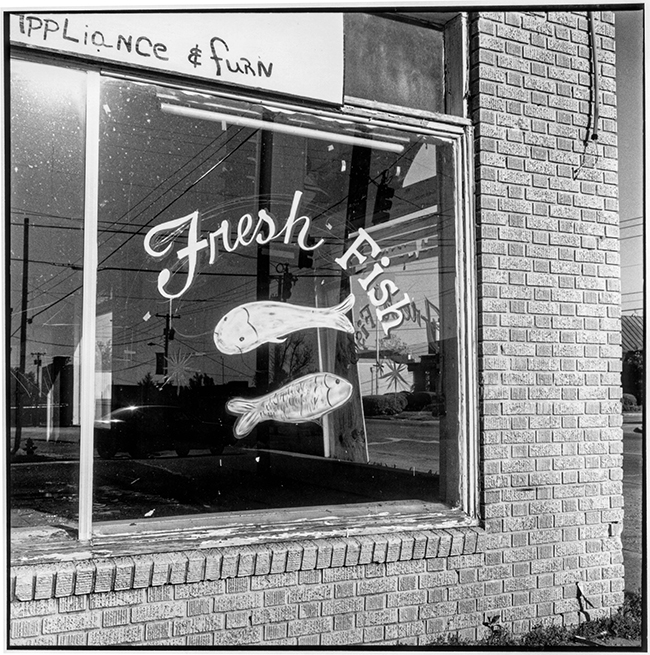

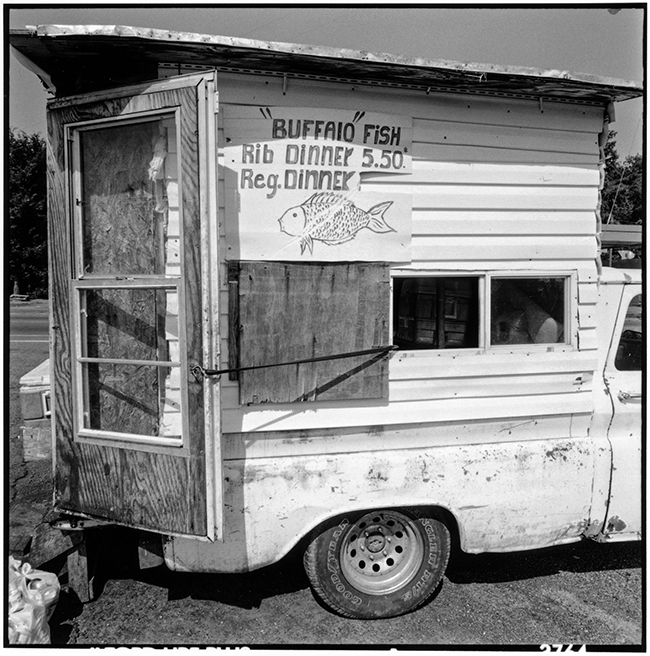

Fresh or Fried: A Southern Cultures Seafood Reader

Twelve fish(ish) tales from the archives (with accompaniments). Read the whole platter here.

This is an expanded version of “Food Matters” from Vol. 21, No. 1: Food.

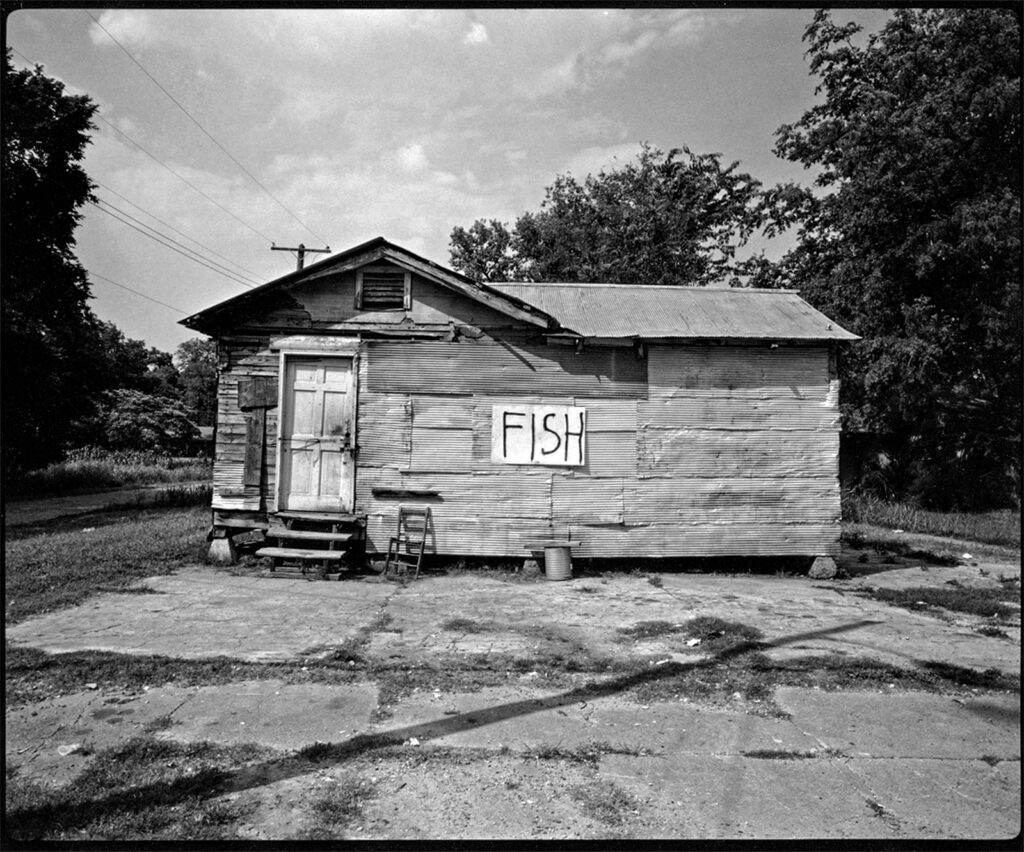

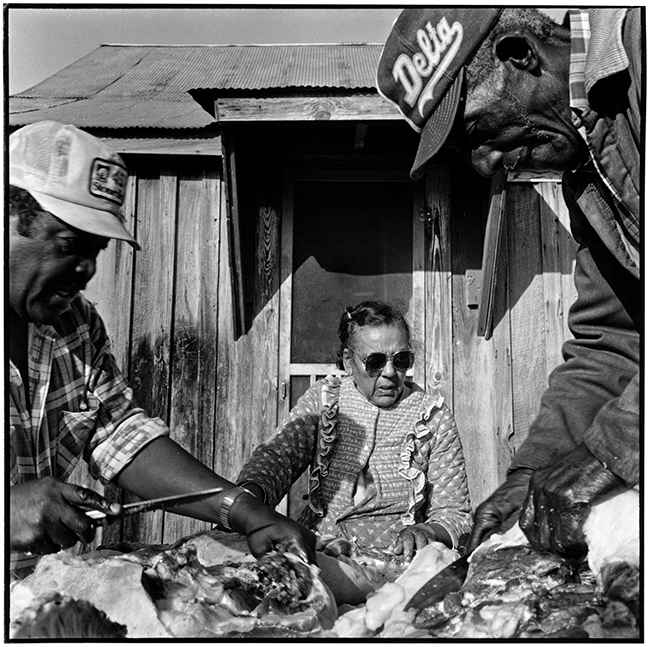

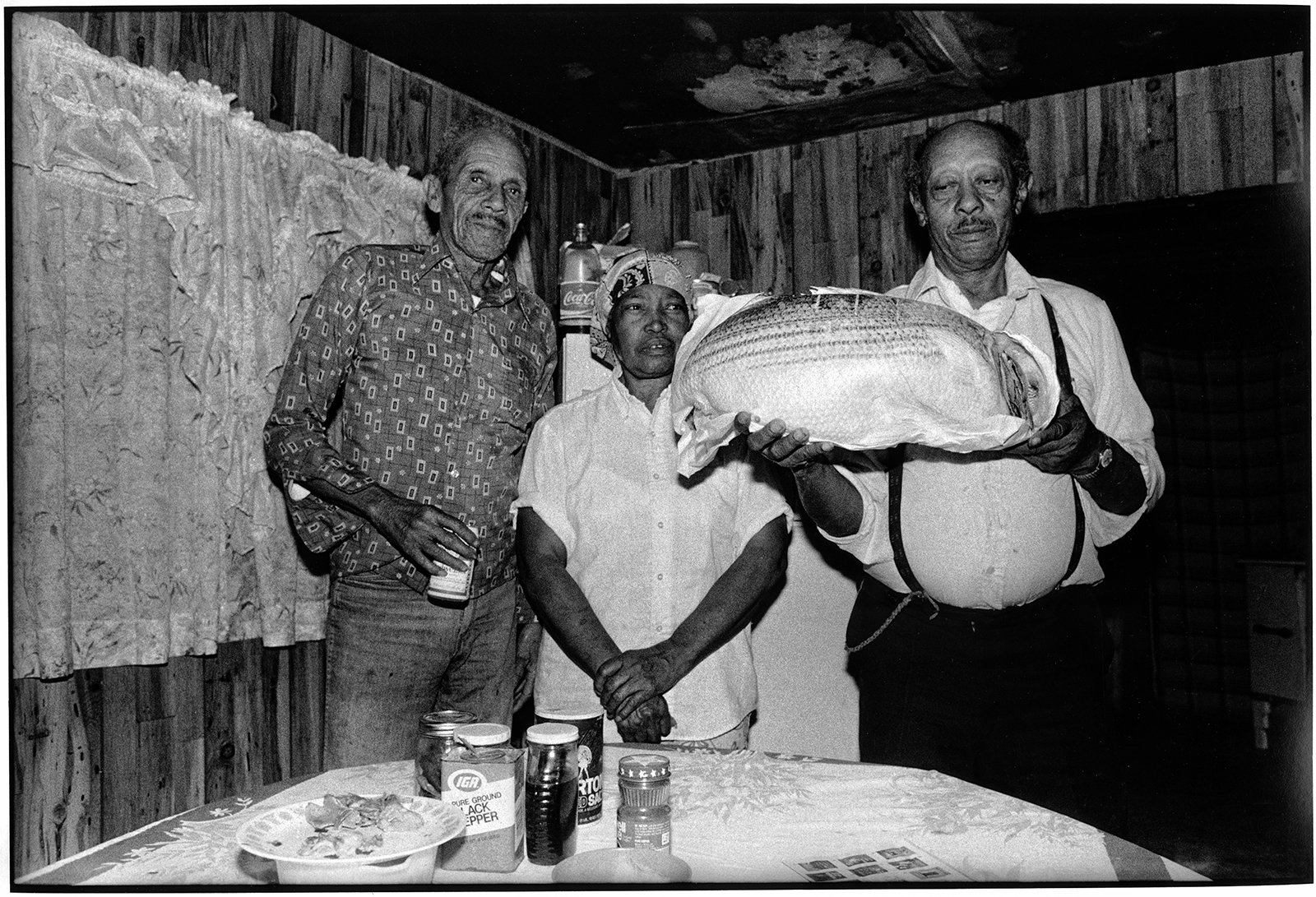

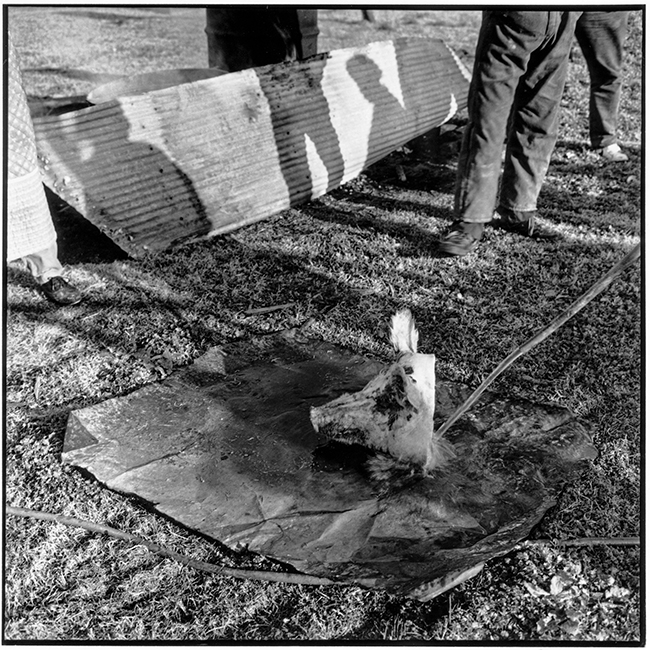

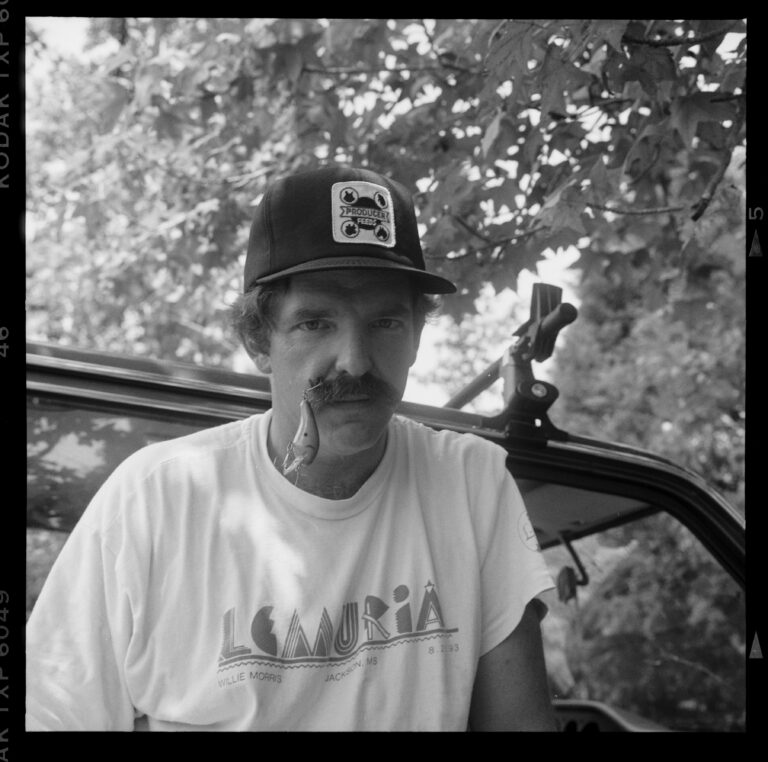

Tom Rankin is Professor of the Practice of Art, director of the MFA in Experimental and Documentary Arts at Duke University, and former director of the Center for Documentary Studies. A photographer and writer, his work has been published widely in numerous magazines, journals, and books, and his photographs are included in numerous private and museum collections. Among his many productions is the seminal LP record “Great Big Yam Potatoes”: Anglo-American Fiddle Music From Mississippi, featuring 16-page booklet on Anglo-American fiddle music recorded in Mississippi in 1939. His books include Sacred Space: Photographs from the Mississippi Delta (1993); ‘Deaf Maggie Lee Sayre’: Photographs of a River Life (1995); Faulkner’s World: The Photographs of Martin J. Dain (1997); Local Heroes Changing America: Indivisible (2000), and One Place: Paul Kwilecki and Four Decades of Photographs from Decatur County, Georgia (2013), and, with his wife Jill McCorkle, Goat Light (2021).