"They portray mountain people like we are all these dumb barefoot hillbillies. I think country people are the smartest people in the world, and I've been everywhere." —Dolly Parton¹

“Dolly, where I come from would I have called you a hillbilly?” asked Barbara Walters in 1977. “If you had, it would have probably been very natural, but I’d have probably kicked your shins,” replied Dolly Parton, continuing, “We’re the ones you would consider the Li’l Abner people, Daisy Mae, and that sort of thing—they took that from people like us. But, we’re a very proud people. People with class—it was country class, but it was a great deal of class.”2

What Dolly Parton understands is that the “hillbilly” aspects of her upbringing, her origin story, endear her to people who share that background and create an unmistakable air of authenticity for those who don’t. Her “dumb blonde” is not so dumb (and not so naturally blonde either, as she’s fond of saying). Parton’s hillbilly brand subverts the familiar stereotype, always rendered as white and usually barefoot. Hillbillies like to sing and hate to work. These cartoon mountain folk tend to have one of two faces: simpleminded and lazy, but harmless—too stupid to damage anyone but themselves—or violent, drunken louts who are incapable of controlling their sexual urges. Fueled by moonshine, the hillbilly is likely to fire a blunderbuss to scare off outsiders and/or is prone to try to have sex with anything that moves (including blood relatives and livestock). Overalls and a big floppy straw hat is, of course, the outfit of choice for the fellas. Hillbilly women get a similar treatment—curvaceous and usually blonde, they are presented as man-crazy, oversexed, and just as dim as their male counterparts. (A favorite conceit of hillbilly comics and cartoons is a voluptuous bride, or her father, marching a hapless boyfriend down to the church at gunpoint—the shotgun wedding.) It is this caricature that Dolly Parton plays to. Blonde, buxom, and beautiful, she was like a country music version of Li’l Abner‘s Daisy Mae Scragg come to life.

Daisy Mae is as responsible as any character for the popular notion of a hillbilly vixen. Created in 1934 by cartoonist Al Capp as a romantic foil for his good-natured but dimwitted hero Li’l Abner, love-struck Daisy chased Abner all over their fictional hometown of Dogpatch, Kentucky. Daisy wasn’t any smarter than Abner, but she wasn’t quite as lazy; she had a man to catch. Her scant outfit has become something of a trope itself—a polka dot peasant top and a skirt torn at the hem is often used as shorthand for a hillbilly pinup. Daisy Mae must have had some resonance with Parton, who posed on a hay bale in a replica of Daisy Mae’s outfit for a 1978 poster, and then a decade later, in 1989’s “White Limozeen,” sang of a heroine who sounds more than a little like Parton herself. A “hometown girl” with “eyes full of stars [and] a heart full of dreams” who comes to the big city seeking stardom, Parton describes her as “Daisy Mae in Hollywood.”3

In the early years of Parton’s career she played a bit of the hometown girl with starry eyes. It seems hard to imagine now, but in early interviews with national figures like Johnny Carson and Barbara Walters, Parton seems earnest, bashful, and sometimes even a little embarrassed, but—and this is important—never outmatched. She bends the hillbilly stereotype in the direction that suits her, not least in her own life story, which has become the stuff of country music legend: she was born to sharecropper parents in a one-room cabin, delivered by a doctor who was paid with a sack of cornmeal. One of twelve children, she jokes that her family was so poor “the ants used to bring back food they’d taken from us because they felt sorry for us.” When Parton was growing up, her family had to do without electricity and indoor plumbing—hardscrabble facts that are repeated, and perhaps more repeated than any other details, in Parton’s biography. Part of a genre predicated on authenticity, Parton’s biography rings as true as any in country music. To paraphrase David Allan Coe’s song: if Dolly Parton ain’t country, I’ll kiss your ass.4

Country music historian Bill Malone describes Parton as a member of “the last generation of performers who really had direct working-class roots or who could recall rural experiences,” observing that successive generations have been “increasingly region-less, classless, and suburban in residence and values.” Parton is a link to a kind of country music that barely exists anymore. What separates her from the other members of this “last generation” is that, unlike Loretta Lynn, Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, or Willie Nelson, she was born after World War II. But her roots in the mountains carry a Depression-era ethos (and legacy of poverty) associated with the greatest generation of classic country artists a generation older than she is. Haggard, Owens, Lynn, and Nelson were born during the Depression; Bill Monroe and Ernest Tubb formed their first bands and Hank Williams Sr. came of age during it. Parton feels like she is of an older era because she is from a place where, for many mountain families or communities, the Depression came early and never left. Fusing Depression-era ideas about poverty with geography creates an easy (if lazy) critical shorthand that demands an impoverished background from people who come from Appalachia.5

She bends the hillbilly stereotype in the direction that suits her, not least in her own life story, which has become the stuff of country music legend.

A big part of why the hillbilly archetype cuts so deeply through our culture is poverty. It tacitly excuses the lack of opportunities some people have. Someone born poor in a downtrodden community has a harder time achieving success than if they were born in a financially more advantageous locale. Much of our popular images of Appalachia make excuses for economic inequality. They tell us that hillbillies are poor because they are lazy; they live in ramshackle homes because they like to be close to nature, and they are uneducated because book learning doesn’t make any difference in their world. The cartoon tries to wash away the complex nature of poverty with the same old pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps fantasy that has coursed through American thought for generations. Stereotypes act to deflect empathy for impoverished people, and a focus on personal characteristics (read: bad character)—“welfare queens,” shiftless immigrants, lazy hillbillies—obscures the knotty economic and social realities that might challenge our rhetoric about self-reliance. After all, how’s a barefoot bumpkin supposed to pull up his bootstraps?

There was, and still is, a great deal of poverty in Appalachia. For many outsiders this fact has become a defining characteristic, but it is, of course, not one that is universally true. Like any large geographic and cultural region, there is no shortage of diversity in the mountains, including rich, educated, and ambitious people. Nothing about the hillbilly image is necessarily “true”—except to say that it sells really well. Ten years before Al Capp introduced readers to Daisy Mae and the other residents of Dogpatch, producer Ralph Peer was marketing white southern music by folks including Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, whom he recorded at the legendary Bristol Sessions in the small Appalachian city of Bristol, Tennessee, as “hillbilly records” (black musicians such as Mamie Smith recorded what Peer deemed “race music”). Hillbilly as a genre hung around until the 1950s, when a new kind of billy—the rockabilly—came along, incorporating rhythm and blues. Hillbilly fell out of favor for the more respectable sounding “country music.” In 1958, a collection of Nashville executives formed the Country Music Association, which sought to “elevate” the genre. “Country and Western” (eventually, simply, “country”) became the favored nomenclature. Nashville performers moved away from farm-inspired attire and toward Western styled clothing and hats. Hillbillies were once again relegated to the mountains.6

In a 2014 interview with Southern Living, Parton claimed the hillbilly moniker, as she’s long done, saying, “To me that’s not an insult. We were just mountain people. We were really redneck, roughneck, hillbilly people. And I’m proud of it.” And of the other term that tends to get thrown at folks from the mountains, she proffered, “‘White trash!’ I am.” Parton continued:

People always say, ‘Aren’t you insulted when people call you white trash?’ I say, ‘Well, it depends on who’s calling me white trash and how they mean it.’ But we really were to some degree. Because when you’re that poor and you’re not educated, you fall in those categories. But I’m proud of my hillbilly, white trash background. To me that keeps you humble; that keeps you good. And it doesn’t matter how hard you try to outrun it—if that’s who you are, that’s who you are. It’ll show up once in a while.”7

In reading such interviews with Dolly, it becomes apparent how masterful she is at owning a conversation. In addition, it becomes clear that many of her one-liners are well honed and oft-repeated to emphasize a specific narrative couched not in self-pity but in humor. “We didn’t have any electricity except for the lightning bugs. If fireflies were out, we’d catch them in a mason jar and put them in our bedroom!” Parton once kidded on the Nate Berkus Show. “We did have running water . . . we would run and get it. [laughs] Most people have four rooms and a bath; we had one room and a path. We had the little outdoor shack out back. It was a good life, and I loved growing up in the mountains. We were really just people, and God and family meant everything to us.”8

A line Parton is fond of using, particularly when she’s on stage, references her eleven siblings: “My parents weren’t Catholic, they were just horny hillbillies!” In this line, Parton claims a hillbilly persona—including pop culture’s notion that hillbillies are supposed to be horny—while complicating another hillbilly trope: that of the buffoon. Even someone with a cursory understanding of Parton’s career knows that she is tremendously savvy and successful. She’s brilliant. So, Parton—nobody’s dumb hillbilly—takes on the stereotype while also subverting it. She beats everyone to the punch.9

In his examination of the socio-historic implications of hillbilly souvenirs, historian Patrick Huber argues that the upheaval of racial norms during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement left those who had previously relied on racial stereotypes to market and define the South looking for more innocuous alternatives. The hillbilly provided a recognizable icon for white tourists that was less confrontational to post-1960s sensibilities than the “mammies” and “pickaninnies” that dominated southern tourist souvenirs in the first half of the twentieth century and before.10

Hillbilly imagery has proven to be remarkably resilient, clinging on even into the twenty-first century as a figure on which Americans can project feelings of regional and class superiority. The rise of white “redneck” reality TV over the last decade, like Hollywood Hillbillies, Duck Dynasty, Moonshiners, and Hillbilly Hand Fishing, reflects commercial media’s continued tolerance for, and exploitation of, the trope. Similarly, hillbilly-themed (sometimes “white trash”) parties remain persistently popular on college campuses. Students don overalls, blacken teeth, and go barefoot. Men accessorize with long fake beards or straw hats, while women wear curlers in their hair and stuff pillows in their tops to look pregnant, sometimes darkening an eye to suggest abuse.

While popular images of the hillbilly are implicitly racial—a black hillbilly generally isn’t part of the vernacular—”white trash” is, obviously, an explicitly racial term. The phrase is likely as old as hillbilly; its origins date back at least to the Antebellum South. In 1854, Harriet Beecher Stowe used the phrase extensively in her Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the follow up to her famous novel, written as a rebuttal to southern claims that she had neglected the “benevolent” aspects of chattel slavery. “White trash” is a term that is rooted in notions of white supremacy; someone who is white trash has forfeited the supposedly innate superiority granted them by virtue of their whiteness. They should, this line of reasoning goes, be at the apex of the racial ladder, but their poverty and lack of sophistication situate them below.11

Remarkably, “white trash” seems to be more a pernicious term in public discourse than “hillbilly,” as evidenced by the continuing popularity of white trash costumes and themed events. In 2012, a health care lobbying firm held a white trash-themed networking event on Capitol Hill. The “White Trash Bash” is a staple on college campuses and white trash and hillbilly costumes abound in costume shops and Halloween stores. One party-planning website offers this summary of these kinds of parties: “Celebrate the South, trailer parks and Wal-Mart parking lots. Don’t worry about being trashy; grow out that mullet and start stocking up on Bush [sic] Light beer because it time to throw a White Trash party!”12

Perhaps what most separates the closely linked terms is place. “White trash” lack specific roots. The term is used to refer to all impoverished whites, including Oklahoma’s Okies or Florida’s “crackers.” On the contrary, hillbillies reside in a specific set of hills—Appalachia and the Ozarks, which, though separated by some 600 miles and the Mississippi River, are often lumped together as the Mountain South, or carelessly interchanged. For example, The Beverly Hillbillies (1962) are usually depicted as moving from the Ozarks to California, though Daisy Moses (known as Granny by all) sometimes refers to her home in Limestone, which is near Johnson City, Tennessee—firmly in Appalachian territory.

Building on earlier popular cartoons like Li’l Abner and Barney Google and Snuffy Smithof the 1930s and 1940s, shows including The Beverly Hillbillies, Petticoat Junction (1963), and Hee Haw (1969) were part of a post-war situation comedy boom filled with southern “home-grown hijinks” and innocent spectacle. The popularity of these shows spurred a desire to see the “real” thing, and entrepreneurs in the mountains obliged. Attractions like hillbilly miniature golf, souvenir stores, and country dinner shows began to appear near the entrance to the Smoky Mountain National Park. Tourists were delighted with the displays they found in Sevier County, which were largely constructed not out of local custom or necessity, but to meet the expectation of outsiders. And so, in addition to pickin’ or shinin’, tourism became an authentic local tradition.13

In the early 1950s, Hugo Herschend and his family moved from Chicago, Illinois, to Branson, Missouri, and secured a lease on Marvel Cave. But before Hugo could enjoy his new purchase, he died suddenly of a heart attack in 1955, leaving his wife Mary and son, Jack, who was fresh out of the Marines, to manage the cave. As part of a series of renovations, Jack opened an above-ground attraction, Silver Dollar City, in 1960.14

Jack’s brother Pete moved down a year later and began marketing the mountain theme park with TV tie-ins, enlisting actors from Car 54, Where Are You? to make appearances at the park’s opening, and later, in 1967, filming five episodes of The Beverly Hillbillies on site. It was a hit. The following year, attendance reportedly increased by sixteen percent. Having cornered the market in Branson, the Herschends looked to expand. They found the precursor to Dollywood, Goldrush Junction, which was attracting tourists but losing money. In 1976 they purchased the Pigeon Forge park and rebuilt it as a twin of their Branson theme business. Then in the early 1980s, Dolly Parton made it known that she was interested in establishing a theme park near her hometown. Rather than compete with Parton, the Herschends offered her a piece of their place, making her part owner, changing the name to Dollywood, and giving Parton creative control. Parton has little to do with the day-to-day management of the place. “I don’t even want to know about that,” she says. “The success of both Dollywood and Dixie Stampede comes from our ability to each work in the areas of our expertise. Because believe me, if I were in charge of the daily operation, I know I would give away far too many tickets, and certainly colas and ice cream, to all the kids!”15

Parton joined forces with the Herschends because she wanted an attraction unlike any that had ever been—a Disneyland for the mountain South. “I’ve always joked that I want to be a female Walt Disney,” she says. “In my early days, I thought if I do get successful, I want to come back here and build something special to honor my parents and my people.” What she did not want was a park filled with roller coasters and generic stereotypes. “I’ve always been aggravated about how they portray mountain people in Hollywood,” she’s said. Instead, Parton wanted mountain tourists to see what mountain life was all about, and to celebrate the local craftspeople and musicians. Parton biographer Stephen Miller describes the folkloric work conducted by the theme park, arguing “Dollywood has subsequently pursued a policy of research, sometimes with the use of scouts, to find people who still possess these traditional skills and find a place for them. In this way the park has helped to maintain and preserve crafts which might otherwise have died out.”16

Crafts were present at Dollywood even before Parton became involved. What was originally a blacksmith’s stand that made souvenirs for theme park goers has expanded to include blacksmiths, leather workers, carvers, potters, glass-blowers and various other craftspeople who make wares while interacting with park patrons in a section of the park without rides known as “Craftman’s Valley.” Unlike, say, Colonial Williamsburg, the craftspeople at Dollywood aren’t playing characters despite their old-fashioned uniforms. On one occasion, I asked one of glassblowers how he liked life at the park. His answer was candid, current, and concise: “This is one of the only places I know of where I can make a good salary blowing glass.” Many of these artisans have been invited to work at the park by the Herschends, who, like Dolly, also wanted to bring visitors closer to mountain life by demonstrating local crafts—a practice that dates back to the very earliest sites of Smoky Mountain tourism. Handicrafts have had strong tourism ties to the mountains for generations, and especially since the handicraft revival of the early twentieth century. This was led in large part by the settlement schools, a social reform movement that attempted to create an Appalachian culture based on the small scale crafting of easily marketable goods like baskets and pottery.17

It is not totally accurate to draw a straight line from Pi Beta Phi’s settlement school, Arrowmont, in Gatlinburg to Dolly Parton’s Craftsman’s Valley, but there are shared ideas. The women of Arrowmont were dedicated to cultural preservation and education. (They founded Gatlinburg’s first public school.) Arrowmont and similar folk schools like Penland School of Crafts and John C. Campbell in North Carolina, and The Hindman Settlement School in Kentucky, were founded on the notion that fostering traditional crafts might provide Appalachia with financial opportunities and also instill a sense of pride in community. It may be a stretch—but not a huge one—to think that in its own inimitable way, Parton’s park is doing that work, too.

Scholar and author Mark A. Roberts, who claims Granny Ogle of Dollywood’s Granny Ogle’s Ham and Bean Restaurant as a relative, has written extensively about the cultural impact of hillbillies within Appalachia and argues, “Many Dollywood visitors gain a sense of their cultural selves from their tourist experiences.” In his dissertation, Roberts relays a story about the Muncy sisters in West Virginia who take him to see their family homestead. They travel by four-wheeler through woods and over hill and holler to get to a family clearing, where they come upon a wooden stage for performances that seems clearly modeled after a certain somebody’s theme park. “The hand-painted signs directing family and visitors to various parts of the homestead, the music stage set up specifically to be viewed from the front porch of the house, the image of the hillbilly finely illustrated on the side of an abandoned trailer—all these details created a place that felt like an amusement park,” writes Roberts. “[I]t resembled Dollywood’s simulated makeshift structures, its music stages designed to appear rustic, its repeated depiction of hillbillies. But the Muncy homestead was real, or was it a simulation of a simulation?” To answer Roberts’s question, it’s both. It is an authentic reproduction.18

Dollywood is not separate from this history of a constructed narrative of Appalachia, but is very much part of it. While for many, Parton was just a physical embodiment of Daisy Mae Scragg, in life she has proven to be so much more. She played to this image onstage, but played against type off-stage, proving herself one of American music’s savviest businesswomen, a generous philanthropist, and a leading advocate of the region. Now that region, her region, is home to Dollywood, the only amusement park in the world dedicated to a woman’s life and history.19

Dollywood reflects real culture, just as it also repackages and re-presents it largely for entertainment and financial profitability. At least some of what today gets sold as hillbilly or mountain culture certainly evolved out of a desire to entertain tourists who have tramped their way through the mountains for more than a century now. And elements of the stereotype are certainly true. Poverty, for example, is obviously a very real thing. That reality makes it possible to manufacture the cartoon of the broke mountaineer. As Dolly proves, shaping your culture into an image that pleased visitors was (and is) a lucrative maneuver. The glassblowers and leather crafters may well have deep historical antecedents in the hills but they also owe a debt to Barnum and Disney.

The hillbilly makes Dollywood both possible and interesting. Without a commercially viable “hillbilly” brand, the businessmen who built the original park would have been far less likely to see Appalachia as a sound investment. And without Dolly Parton and her tacit critique of hillbilly buffoonery, the park would be just another cluster of roller coasters on the map of American tourist traps.

The hillbilly is a complicated thing. How can it at once be a load of crap, a (mildly) subversive icon, and an assertion of identity? Because we need stereotypes—not to pigeonhole other people, but to construct our own identities.

On November 23, 2016, a fire was sighted in the Smoky Mountain National Park. It was, at that time, about the size of a football field. But a historic drought and a series of unpredictable winds quickly spread the flames, and the fires consumed acre after acre in the park and then tore through Sevier County. Hamstrung by power outages and downed cell service, efforts to evacuate Gatlinburg were left to first responders who went door-to-door in an effort to clear homes in the blaze’s path. In the end, the fire consumed more than 17,000 acres, destroyed or damaged 2,460 buildings, and killed fourteen people. Hundreds of Sevier Countians were rendered homeless. Because of the nature of the evacuation, many residents were unable to save even basic necessities from their homes.20

With her home county devastated it came as no surprise that Parton stepped in to help. What might have been surprising, to some, was the extent of her charity. Before she had raised a cent of outside funds she promised to provide each family that lost a home $1,000 a month for six months. She called the project the “My People Fund,” which borrows its name from a show at Dollywood that features members of the Parton family.

Then Parton asked for help. Lodge, a venerable East Tennessee cast-iron manufacturer, made a special skillet and gave $15 from each one sold to Dolly’s foundation. The skillets sold out in four and a half hours. Lodge rearranged their production schedule to make more, which quickly sold out as well. In about ten days the skillets had raised about $100,000. Parton also broadcast a telethon featuring performers like Kenny Rogers, Chris Stapleton, and Reba McEntire. Others called in to give donations, including Taylor Swift and Paul Simon, who donated $100,000. All told, Parton’s broadcast raised over $9 million. During the telethon, Parton broadcast clips of some of the people who had lost their homes. Parton claimed them all as My People—hillbillies, white trash, and all.21

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

Graham Hoppe lives and works in Raleigh, North Carolina. He writes about culture and history with a focus on food and music. His first book, Gone Dollywood, was published in 2018 by Ohio University Press. Find more of his work at grahamhoppe.com.

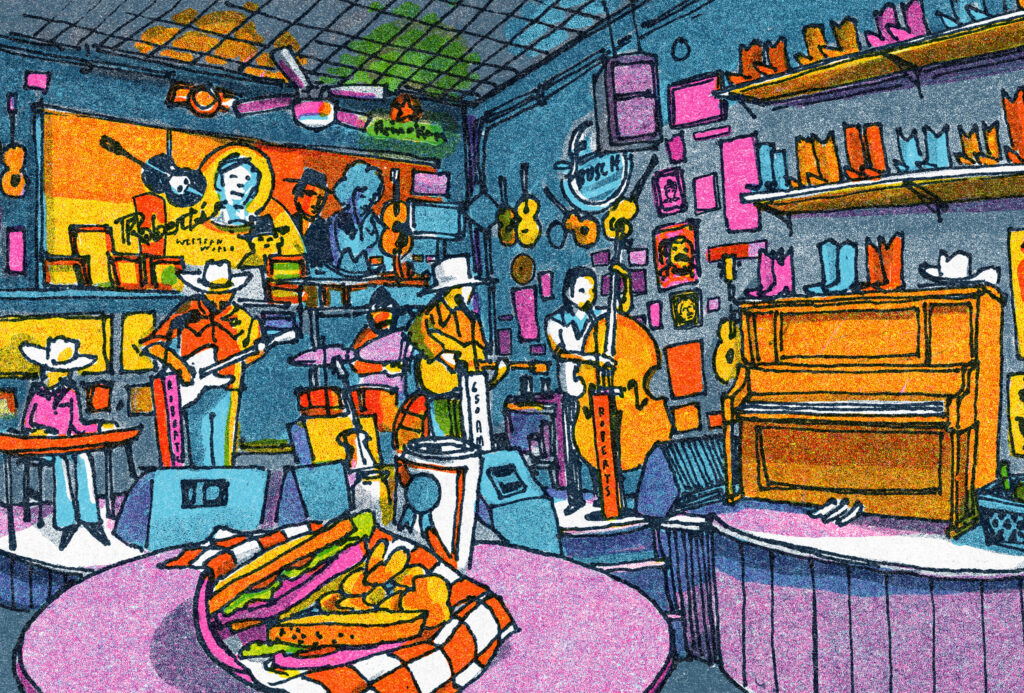

Tammy Mercure was named one of the “100 under 100: The New Superstars of Southern Art” by Oxford American magazine. She has a BA from Columbia College Chicago and an MFA from East Tennessee State University. She lives in New Orleans, Louisiana. See her work at tammymercure.com.

Header image: Pigeon Forge, TN, 2008.

NOTES

- Dolly Parton, Dolly: My Life and Other Unfinished Business (New York: HarperCollins, 1994), 305; David Allan Coe, “If That Ain’t Country,” by David Allen Coe, Deborah L. Coe, and Fred Spears, In Rides Again, Columbia, 1977.

- Bill C. Malone, Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 86.

- David Sanjek, “All the Memories Money Can Buy: Marketing Authenticity and Manufacturing Authorship,” in This Is Pop: In Search of the Elusive at Experience Music Project, ed. Eric Weisbard (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 158; Bill C. Malone, Southern Music, American Music (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1979), 130.

- Jennifer V. Cole, “Dolly Parton: The Southern Living Interview,” Southern Living, September 11, 2014, accessed January 16, 2017, http://thedailysouth.southernliving.com/2014/09/11/dolly-parton-the-southern-living-interview.

- Dolly Parton, interview by Nate Berkus, The Nate Berkus Show, Syndication, September 15, 2010.

- Kitty Empire, “Well hello again, Dolly,” The Guardian (UK), March 24, 2007, accessed January 16, 2017, http://www.theguardian.com/music/2007/mar/25/popandrock.features2.