I think I’d been there five minutes when Larry pulled up alongside me in a golf cart, abruptly. My camera dangled from my neck as I approached him. “You know there’s a fifty dollar fine for taking photos in Love Valley.”

“Oh, well . . . I didn’t think . . .” I muttered.

“I’m just kidding with you, girl!” he wheezed. “You ain’t from around here, huh? What’re you doin’ in Love Valley, girl?”

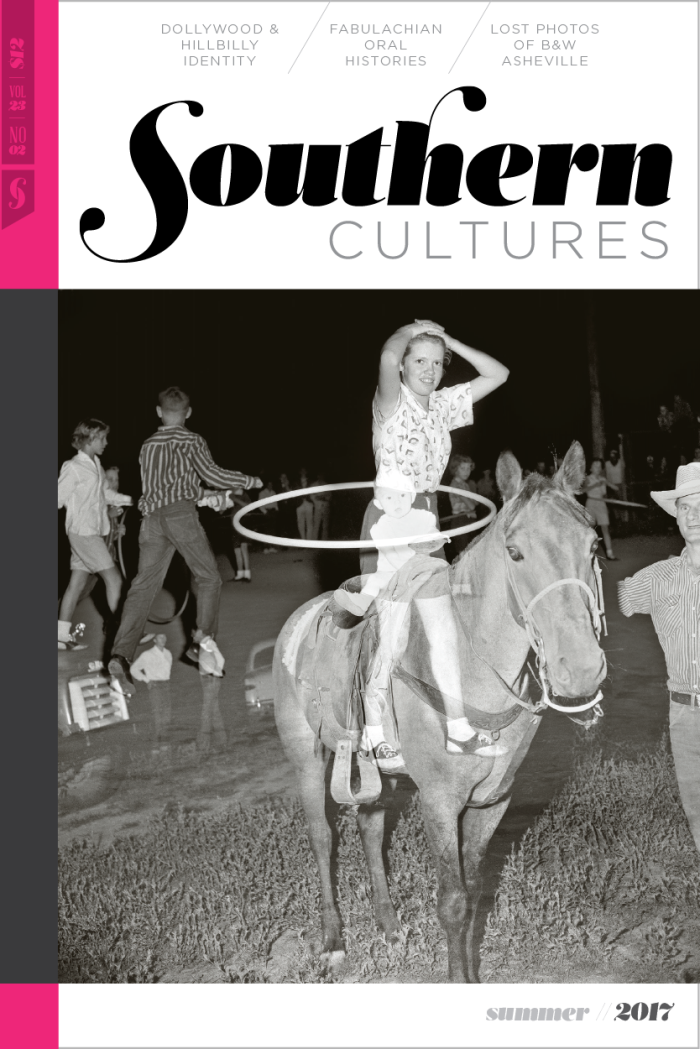

Good question. I liked Larry. “I just came to check it out.” I first saw Love Valley on Visit North Carolina’s tourism website under the “quirky” section of “Things To Do.” It promised me that I would depart from the ordinary when arriving in this remote town nestled in the foothills of the Brushy Mountains. In its brief description the .2 square mile town was declared a “Cowboy Capital,” the only place for cowboys East of the Mississippi. I hoped all ninety-eight residents would prove it to me.

Another golf cart whizzed past. A man who looked like Larry drove one-handedly in a cowboy hat and sleeveless T-shirt, his wife watching the world pass from the back seat while stroking her pet Chihuahua.

“You want a tour of Love Valley? I’ll take you on a tour. Get in!” I hesitated but jumped in alongside Larry. “You want a beer?” he asked, as he cracked open a Bud Light from under the seat. To be honest, I couldn’t hear much of anything he said to me over the cart’s engine and his slurred speech. In the bar afterwards, Larry’s friend Patch (for his patched eye) told me to be careful. Patch was on America’s Most Wanted List. I checked later. Nobody in our nation’s lineup quite resembled him, but, yes, I thought, I should be careful. While the signs encouraged me and other women to be a cowgirl and “PARTY ’TILL HE’S CUTE,” I calmly drank in the words of my new friends and the neon essence of the Busch Light, Miller Lite, Natural Light, Bud Light, Coors Light, and Michelob Ultra logos on the walls. On the way out I read another sign: “MY NEXT HUSBAND WILL BE NORMAL.”

Love Valley was established in 1954 by the late Andy Barker, a successful contractor from Charlotte, North Carolina, who at the age of thirty uprooted his wife and two children to this remote area of the Piedmont’s rolling hills. He had one dream: to build an old Western town, a valley that would embody “a boy’s dream and a man’s reality.” He had dreamt of this idyllic town while serving in the war, writing descriptive dream letters to his mama back in the US of A.

Dear Momma,

Been in a fox hole all day—tonight I’m thinking and planning . . . my western town . . . best idea yet since I’ve gotten my new partner, the Lord. I’m bound to make it. I know that with Him, my purpose and complete faith, anything is possible. My part of the bargain is to build a town, a Christian Community with clean recreation and strive to help people know more about God and His outdoors. I know I’d never make a preacher, but can build a church and help out personally in many ways. We can keep young boys occupied and out of trouble by letting them help run the place.1

A recreation of pioneer days, only horses and foot traffic are allowed on the dirt Main Street. Flash-front stores and saloons bring to mind a John Wayne movie, but also conjure an eerie ghostliness at quieter times of day. I watched a young couple trot by, bouncing on their Confederate flag saddle blankets past the first structure Andy Barker built: the Love Valley Presbyterian Church, situated slightly aslant at the top of Mitchell Trail. The second building constructed was the Love Valley jail, where men were held to dry out in three barred cells by a pot-bellied stove.

I attended Sunday morning service with approximately fifteen others, all lopsidedly seated in the pews on the right. I thought there’d be more people after all of those Cowboys for Christ emblems I’d seen around. There were some stragglers from the night before, folks like Sandi, Jethro, and Bud now praying off a hangover, resting the Good Word on their bellies. A chorus from the evening still rang in my ears, one that had made even me want to scream, “Amen!” It was “Copperhead Road,” by Steve Earle. I had never heard this song before and I most certainly had never seen inebriated cowboys line dance to it. The lyrics tell the story of a Tennessean from a generations-old moonshining family, self-described “white trash.” After being drafted to Vietnam, he returns to his native Copperhead Road to sell marijuana and continue the tradition of the American outlaw. “AMERICAN BY BIRTH. REBEL BY CHOICE.” I saw that written on a canvas bag in the Love Valley General Store. The song opens with layers of a bagpipe-sounding synth and mandolin and becomes a dance for the folk against the Man. It’s about scraping by and generally being a badass. In the Silver Spur, everyone kicked their right foot up behind their left knee to slap their boot heels, a synchronized moment that felt defiant and patriotic. “Copperhead Road” had the power to incite a revolt, or just a bar fight, which also happened the night before and ended in a bloody mess.

To the editor,

. . . Well, we wish to inform everyone that our church does not sponsor any ice cream suppers at Love Valley or anywhere else and especially does not approve of horse racing and such on the Lord’s day because God’s holy word says “Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy . . .” We do not think any true Christian will have any part of these Sabbath day showdeos.

Thank you,

Mr. and Mrs. Sprinkle

The Presbyterian service was short and sweet. When it was over I had to shake hands with lots of people, being a newcomer to the church. Instead of lining up for the Body of Christ and sticking our tongues out at a priest, we lined up in a room next-door for some pulled pork BBQ and coleslaw sandwiches. I sat down next to a frail woman, her hands clasped in her lap, ready to be served. “That’s Miss Ellenora, and I’m Tonda, Miss Ellenora’s daughter. I’m so glad you’ve joined us.” I had heard of Ellenora, the wife of Love Valley’s founder. From across the table I watched Tonda dig her plastic fork through the mushy hamburger roll for a bite-sized piece of pork. “Here you go, Mother,” she said, as she leaned across the table to feed Ellenora one-handedly. Tonda was in her mid sixties with short white-blonde hair that fell just below her ears. Her right arm was in a sling and her left hand wobbled towards her mother’s mouth.

“Welcome to Love Valley,” said Ellenora in a scratchy voice. She held my hand and told me I was beautiful. I held hers and did the same. Ellenora’s skin was a bit wrinkled, but had a healthy olive complexion and glow, and her hair—a beautiful silver and white—was soft, thick, and smooth. I later learned she served in the Navy Women’s Reserve during WWII as a cryptography specialist, decoding messages to and from top Naval officers. At 94 years old, she now suffered from advanced Alzheimer’s and had trouble deciphering simple communication, but she was ready to resurrect nostalgia from the Valley’s early days. She wore a delicate silver necklace with an LV centered in a circle, and twiddled her thumbs often, searching for what to say. “You should stop by,” she said at the end of our conversation over Presbyterian pulled pork. She thought it was the early 1960s, when she still lived in her cabin downtown, monitoring the utopian impulse—the one she helped start, the one that no longer exists. I went with them to Tonda’s house on the outskirts of town, where Ellenora also lived.

Unscramblin’ to get the message. And the letters are all mixed up just like puzzles. These messages come over the wire. They just got scrambled up when they were passing on the wire. It’s hard to remember everything . . . the war ended and there was a lot of hooray and all the excitement. And you were given a check and discharge papers and we went home. Free, let’s put it, free.

“Now, who lives here?” Ellenora asked as we crossed the threshold. “You do, Mother. We were only gone for an hour or so. You live here now. I take care of you.” In some ways, Tonda seemed more weathered than her mother. In her country drawl, she spoke candidly of the troubles she’d had with her mother, with her husband, with the passing of her father. The care of Mother was completely on her. Her younger brother, Jet, died suddenly at an early age. It was all said in a very “It is what it is” tone, delicate but without affect. We walked passed an old photo of Andy Barker, handsome and suave on his high horse. As Ellenora would later assure me, he was very good-looking. Next to her father’s portrait were images of Tonda as a graceful cowgirl adorned with prizes, from the age of seven through her early twenties. She was a beautiful young lady, naturally blonde with a pointed chin and bright white teeth. Her father’s spitting image.

As her mother’s health and mind slid further and further into limbo, Tonda moved back to her home in Love Valley, which had slipped into disrepair after she and her second husband decided to live on the road in their mobile home for a decade or so. We chatted over coffee for hours. Ellenora spoke to me in spits and spats about Love Valley, and Tonda served as a translator of memory. The heyday of this tiny town was from the mid 1950s to the late 1960s. During this time the love was thriving. Ellenora told me that’s why Andy named it Love Valley: “He said, ‘I’m gonna name this town Love Valley because I love people.’ And that’s exactly what we did.” Mr. and Mrs. Barker looked the part of a classic American couple in high-waisted blue jeans and plaid shirts. In the spirit of America’s hero, the cowboy, their avowed intention was to put spurs on every Piedmont citizen. At first they marketed the town as a sort of resort dude ranch, where families could kick up their feet for the weekend, enjoy the outdoors, and ride horses. Then Andy encouraged people to “give love a try” and move there. In 1954, they started building houses and inviting families, members of neighboring towns, and good buddies to relocate. Barker said to a newspaper reporter, “My plan for Love Valley is to provide good, clean wholesome recreation,” and he would not tolerate the profane, intoxicated, or other persons who disregarded “the rules of gentlemanly behavior.” More and more people started coming, and the Love Valley church began congregating outdoors to accommodate all the Westerners in North Carolina.

The Barkers seemingly invented words like showdeo (the combined spectacle of a Western show and a rodeo event) and stompede (an outdoor square dance held in the rodeo arena), both of which were popular on the expansive landscape. Cookouts were also common in Love Valley, and Ellenora prepared meals for large crowds over an open fire. Newcomers started a local newspaper called The Smoke Signal. They opened successful shops—tack and otherwise. And even Belk opened a small department store to sell riding clothes. When town teetotalism was voted down, barflies grinned from ear to ear. Joe Ponder, who opened a leather shop, set Guinness world records for having the strongest teeth—bending steel rods, pulling railroad cars and trucks, smashing cement blocks, lifting women and donkeys, firing machine guns, and once attempting the Death Slide, where he zip-lined fifty feet, holding on by only his teeth, but fell, crushing both of his ankles. Lots of famous people visited; French, Japanese, and Pakistani ambassadors slept over, and President Lyndon B. Johnson once stood waving from a horse-drawn wagon on Main Street.

The area has been in recovery since 1970, when the Allman Brothers came for the Love Valley Rock Festival and brought 150,000 fans or more to the village of 72 people. Tonda convinced her Daddy to let them come. She’d been working in the music scene, and he’d seen the hippies on TV. They were all about love, and they just needed a place to stay. As it’s told, the hippies ruined the town, sold drugs and got reckless, left it a mess. A decent number of “longhairs” stayed behind after the festival, bearded and braless. The community was furious, the town’s image was going the way of the freak. The hippies fought with the local cowboys, then the outlaws came in toting guns and buying the pot that was growing in Love Valley’s fields. Andy Barker ran for governor on the Democratic ticket and lost. The nation’s largest hot-air balloon manufacturing plant, The Balloon Works, opened nearby in Iredell County and employed a good many Love Valley hippies. I gleaned all of this as Cliff Notes from Tonda; Ellenora did not remember this time period, or she had blocked it out. It became clear that even the First Daughter of the Valley couldn’t readily put her finger on the causes for the town’s disintegration. Andy went on sabbatical in the 1980s, I was told, though I wasn’t really sure what that meant.

Numerous Western films used the town’s Main Street as a backdrop—classic Westerns, spaghetti Westerns, zombie Westerns. The 1990s were excessively intoxicated, and Love Valley’s bad reputation was spiraling out of control, shifting from the Cowboy Capital to the Drunk Capital. Roughneck gangs got in fights all the time and motorcycle ride-ins overtook the pleasantries of the horse-drawn buggy. After the economy crashed in 2008, matters got worse. Most residents were either retired, on disability, or unemployed.

I returned to Love Valley in my cowgirl boots, promptly stepping in horse shit. There was a Chili Cook-Off I was told I just had to see. But I missed the chili, or at least I didn’t see it. When I got there, they’d just started to auction off cuts of meat and pecan pies to raise money for Hospice care when it started to rain. I called up Tonda to see how she was doing, curious about what she and Mother might be up to. “You know, I was thinking of you,” she said. “I want to show you something. If you’re through with that chili, why don’t you meet me across from the gift shop.” Of course I’d meet her.

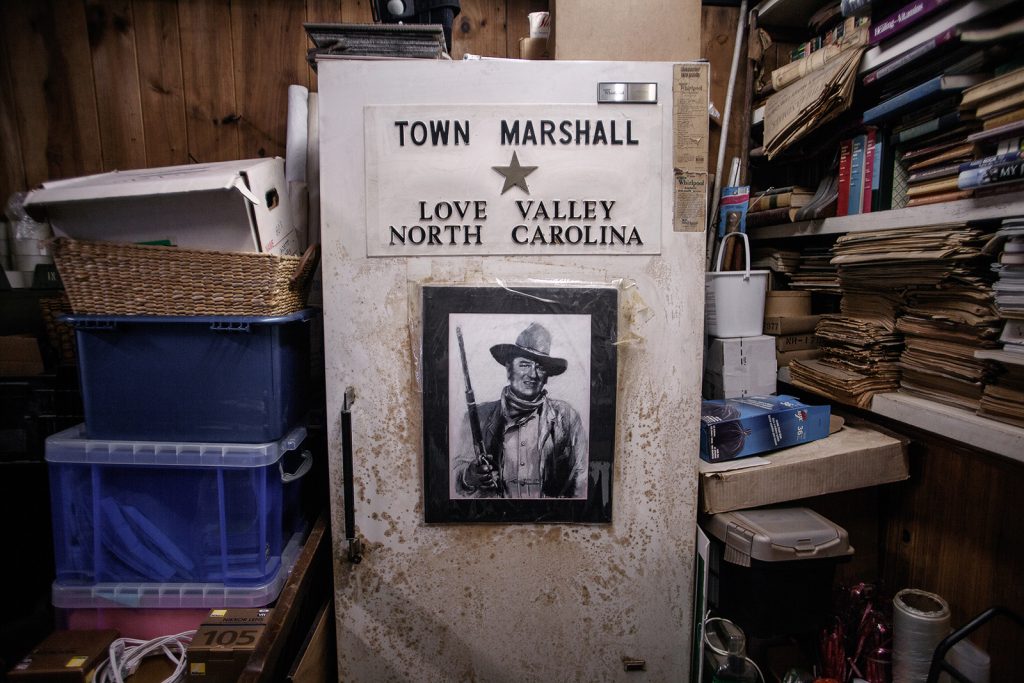

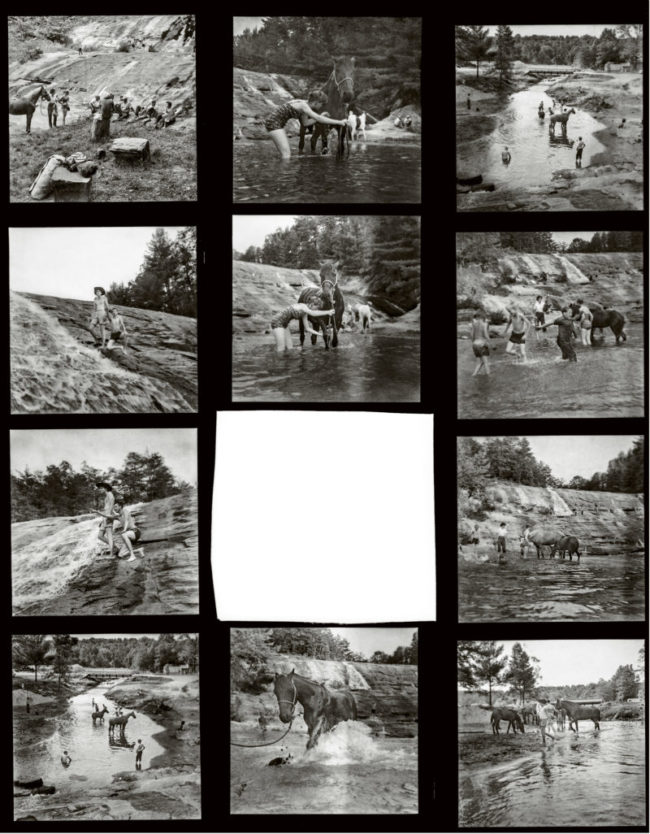

I waited for her on a covered wooden sidewalk outside a saloon-house made of rough-hewn timber. My boots made an authoritative sound upon the planks. When Tonda arrived, she greeted me kindly and hastily made her way to the front door, which opened to an unbelievable site. “This is Miss Ellenora’s old house, where she lived until I came back to help her.” At the top of the front door was a painting of Andy Barker in cowboy hat and scarf. A poster of John Wayne was plastered to a rusting fridge. The rest of the room was shelved, floor to ceiling, with a variety of papers and boxes. “I can’t bring Mother here because she’ll be confused and upset.” She pulled down a box of negatives from the shelf, and I was amazed: they contained Ellenora’s documentation of Love Valley, organized and categorized with her lovely scrawl. Tonda left me alone for five or more hours that afternoon to rove through the past in a sea of photo albums, 4 x 5 negatives, 8 and 16mm film reels, and stacks of scrapbooks.

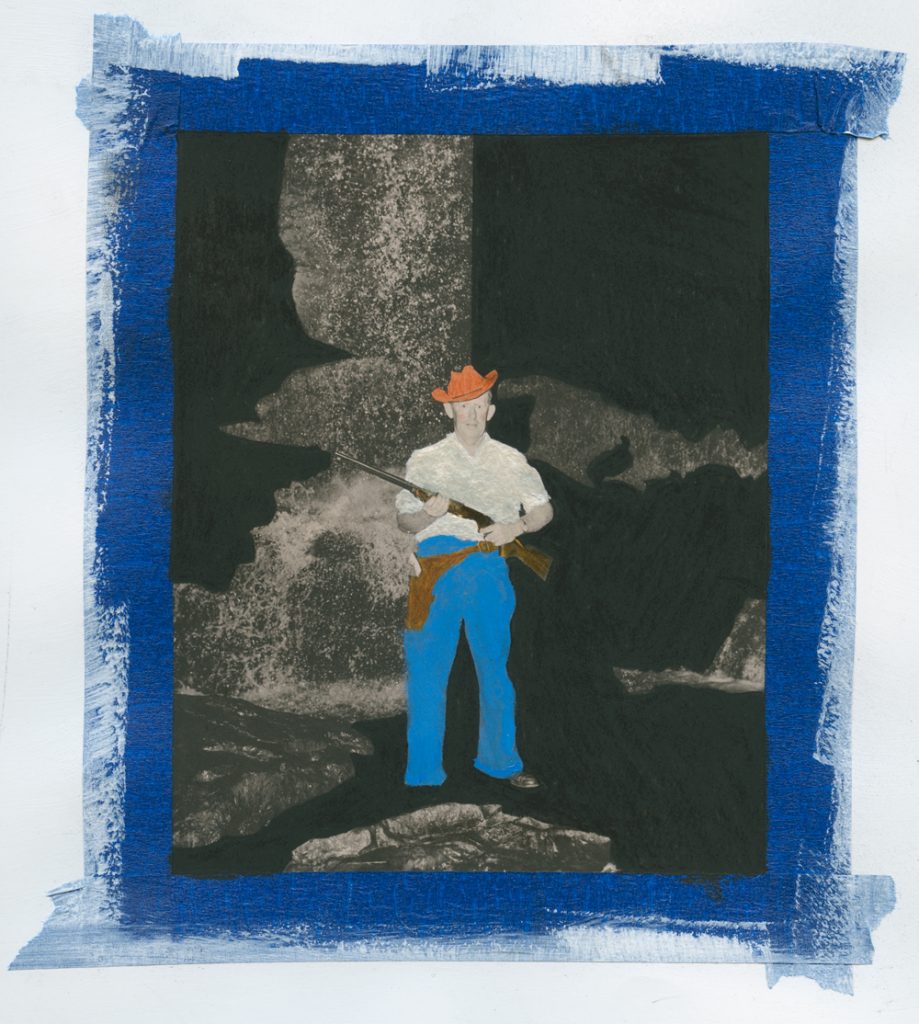

My hands quickly covered in something like soot and dirt. I held the negatives up to the light and saw beautiful rodeo queens in dresses and immaculate cowboys standing tall. Groups cooked around campfires with guitars in hand, and friends circled around to join. The experiment looked to be going well—in fact, it looked ideal. The scrapbooks were full of newspaper clippings, which told the story of Andy’s heroic effort to realize the myth of the Old West. He was described as having unlimited confidence, with a personality well suited for boosterism. He asserted that his love for horses, people, and guns led him to begin this adventure in Iredell County. I also discovered he was the vice president of the North Carolina Gun Collectors Association. A photo revealed a man pointing a gun at Mr. Barker in a sleeveless button-down shirt, his arm slung around cute Ellenora in her short bangs, saddle shoes, and “B” letterman’s sweater.

A loaded gun is a respected gun. No one plays around with a loaded gun, and most accidents happen with guns that people assume are empty.

I knew from Tonda that there were very few people in Love Valley who had been there from the beginning, and so very few there today know the story well, and even fewer know that these memories existed in this room, precious and contained, but disintegrating. I stumbled into a drawer of old film reels. One was called “Old Town Scenes,” another “Miscellaneous Horses.” I unhooked the lid, took out the film, and smelled the pungent scent of vinegar. The chemical reaction of natural change was underway, the emulsion was slipping. I could save these images. I had faith in the Western failure, in Ellenora and Andy’s outsized patriotic dream. Love Valley offered the freedom to be a hero, self-reliant, rugged, and the Barkers’ vision was no gimmick. Today, America plays this game like a reality star, larger-than-life, riding the horse just for the look of it.

This is real, not no showplace.

When Tonda returned hours later she found me on the floor surrounded by dozens of boxes I’d sorted through. The sun would set soon and she wondered what I’d do. I told her I should head home, but I did not want to part with Love Valley yet. I asked her, sheepishly, if it would be possible for me to bring some of these home to work on scanning and digitizing. She sent me off with a handful of boxed negatives, scrapbooks, and film reels. I made my way to my car hurriedly, nervous that anything would happen to these materials in the rain, though I triple-bagged them. As I pulled away from Love Valley, it was dark and the eyes of horses along the hitching rail reflected my headlights. Stray but well-fed dogs waddled on their way to see me out. On the radio I heard “(Ghost) Riders in the Sky” by Riders in the Sky. “Yippie yi ooh,” they crooned. “Yippie yi yay.” And the rolling hills parted.

This essay first appeared in the Summer 2017 issue (vol. 23, no. 2).

Michaela O’Brien is a documentary artist and multimedia producer currently based in Durham, North Carolina. She holds an MFA in Experimental and Documentary Arts from Duke University. Her work includes independent documentaries for broadcast, award-winning audiovisual installations, client-based archival research, and interactive videos for a variety of acclaimed museums. Her moving image and photographic works have been featured in film festivals and galleries worldwide. She is currently teaching in the department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies at Duke University.