“There are certain things you have to do. You’re going to get in trouble, but that’s all right. [Highlander’s co-founder] Myles Horton always said, ‘You’re better known by the enemies you make.’”

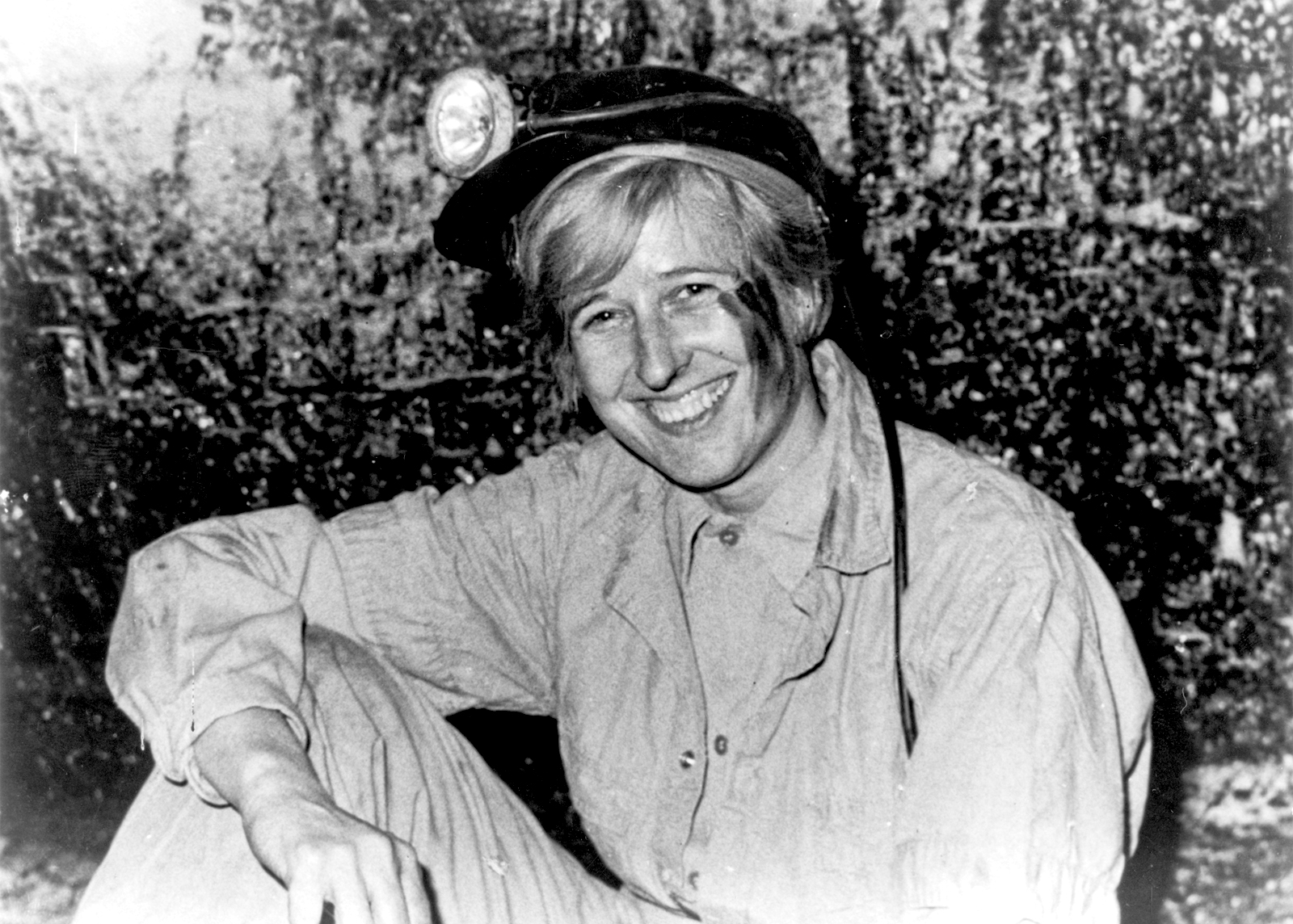

A 1966 photograph of the Appalachian historian and activist Helen Matthews Lewis captures much about a woman who has been studying, writing about, and fighting for the people of Appalachia for three-quarters of a century. In the photo, Lewis sits outside of a mine entrance, hair emerging beneath a hard hat, with a big smile and coal-smeared cheeks.1 It is the portrait of the scholar as coal miner, the worker as scholar, the academic as activist. The image of Lewis in the garb of a coal miner—hard hat, head lamp, and rolled up sleeves—anticipates the 1970s movement of Appalachian women into the male-dominated coal industry following Title VII legislation, while also recalling Lewis’s own history as a trailblazer for women in the academy.

Helen Lewis has long been a towering figure in Appalachian Studies, designing the first academic programs and developing an interpretation of Appalachia as an “internal colony” of the United States, a model that influenced a generation of Appalachian scholars and activists.2 She describes herself as part of the “long movement for women’s rights.” Her experiences as a child in rural Georgia, her education at a progressive women’s college, and her tireless efforts working for justice in Appalachia and the South are emblematic of how a generation of southern women activists who came of age in the 1940s confronted racial, gender, and class discrimination in their native region.

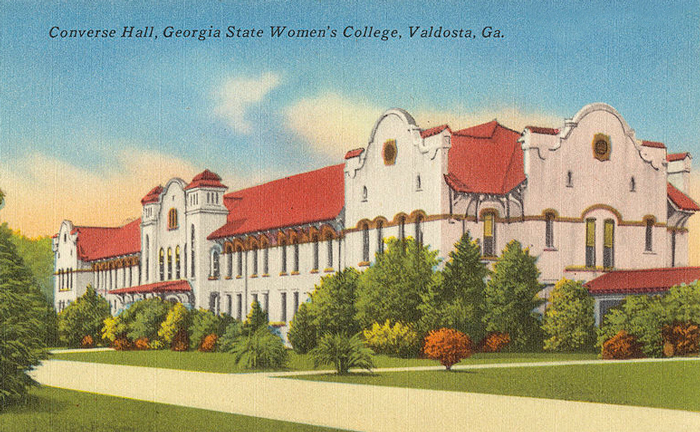

While Lewis’s scholarship has been profoundly influential, her personal story is less known. As she recounts it, early encounters with a range of social movement activities informed her work. Lewis’s activist career began with the YWCA as an undergraduate at the Georgia State College for Women in the 1940s, where she participated in interracial organizing. As she entered graduate school and began teaching anthropology and sociology in the 1950s, she navigated an academic system that discriminated against her because she was a woman and the wife of an academic. After she left academia, she became an important ally and supporter of grassroots women’s activism in Appalachia. Although women’s equality was not always at the forefront of her activism, Lewis’s struggle for gender equality and her awareness of how it relates to class and race equality weave throughout her narrative.

Lewis sits outside of a mine entrance, hair emerging beneath a hard hat, with a big smile and coal-smeared cheeks. It is the portrait of the scholar as coal miner, the worker as scholar, the academic as activist.

She was born in Jackson County, Georgia, in 1924. Her mother was a homemaker and dental assistant, and her father was a rural mail carrier who had high hopes for his two daughters, Helen and JoAnn. Despite her loving and secure family, Lewis witnessed the injustice of the Jim Crow racial caste system. She tells a story of meeting a Black schoolteacher who was on her father’s mail route and whom her father held in high regard. The teacher wrote her name on a card in beautiful calligraphy, and she speaks of cherishing that card and keeping it for years. When she was seven or eight years old, the same man came to her home to see her father. “Mr. Rakestraw is at the door,” young Helen announced to her mother, who was quilting with other white women. “The women laughed because you weren’t supposed to call a Black man ‘Mister,’” Lewis explained. “I was so shamed by that . . . As a child, to be laughed at is a terrible thing.”3

When Lewis was ten years old, she and her family moved to Forsyth County, Georgia, where whites had forced nearly all Black people out of the county in 1912. Her father, who did not agree with the violent treatment of African Americans, used his position as a mail carrier to warn those who did come into town that Forsyth County was not a safe place for them. Lewis says her father provided a foundation of fairness and caring that later influenced her interracial activism during her college years and her work long afterward. Yet, the story about Mr. Rakestraw captures the social contradictions that she faced as a young woman: her mother allowed her to play with African American children—and behaved kindly toward African Americans—but did not question local customs; her father actively tried to protect African Americans from dangerous encounters in the county.

After graduating high school, Lewis headed to Bessie Tift College, a small Baptist women’s school. There she had her first “conversion experience”—the moment when she began to think more critically about race relations in the South. Clarence Jordan, the white preacher who founded Koinonia Farm as an intentionally interracial, religious community in Americus, Georgia, exposed her to a liberal Protestant Social Gospel message: justice and equality should be realized in the here and now. After completing a year at Bessie Tift and taking a year off to work, Lewis entered Georgia State College for Women (GSCW). In the early 1940s, the YWCA sponsored Lewis and a friend as they attended an interracial program in which students worked together on industrial projects at Hartford Theological Seminary in Connecticut. There she lived in integrated cooperative housing with students from across the country. Not only did Lewis have opportunities to travel and meet people from different regions, the Campus Y exposed her to some of the most progressive public figures of her day, including the Presbyterian minister Charles Jones, a leader in the progressive Fellowship of Southern Churchmen, and Lucy Randolph Mason, an organizer for the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). While these people and experiences helped her envision a more just society, she also came face-to-face with the repressive politics of Georgia segregationists. She relates these stories here.

In 1946, Georgia became the first state to allow eighteen-year-olds to vote, and Lewis joined the GSCW League of Women Voters and led a campaign to register young voters. After graduation in 1946, she went to graduate school at Duke University, and there she met Judd Lewis, whom she would soon marry. He wanted to attend the University of Virginia for his PhD in philosophy, so she went with him and completed her MA in sociology in 1949. Her thesis, “The Woman Movement and the Negro Movement: Parallel Struggles for Rights,” draws historical comparisons between the U.S. suffragist movement and the early stirrings of the African American Civil Rights struggle.

In 1955 Helen and Judd both took jobs at the newly opened Clinch Valley College in Wise, Virginia. Marriage policies at the college restricted wives of male faculty from holding full-time positions; thus, Helen taught sociology part-time and worked part-time as a librarian. Not until the late 1960s did she receive a fulltime faculty position in sociology and anthropology at Clinch Valley. In 1970, she received her PhD in sociology from the University of Kentucky, and her dissertation, “Occupational Roles and Family Roles: A Study of Coal-Mining Families in Southern Appalachia,” again showed her ongoing exploration of identity, in this case regional and gender identities among coal field communities.

While the Civil Rights Movement was taking off in much of the South in the 1960s, Lewis lived and worked in rural, largely white communities tackling the oppressive policies of the coal companies that dominated politics in the coalfields of Appalachia. Yet, her activism in Appalachia was not isolated from the insurgent Civil Rights Movement; her work demonstrated similar concerns about equality, economic justice, authenticity, identity, and democratic government as the organizers for freedom in the Deep South. Indeed, Lewis’s academic work forged a connection between her region and the Civil Rights Movement; the Appalachian Studies program she developed at Clinch Valley in the late 1960s influenced a cadre of activists, including grassroots leaders and white Civil Rights activists who migrated to the mountains to build alliances with rural whites. Together, they forged a progressive movement in Appalachia in the late 1960s and 1970s.

While the Civil Rights Movement was taking off in much of the South in the 1960s, Lewis lived and worked in rural, largely white communities…

Lewis’s proposal for the Appalachian Studies program reveals her approach to life in Appalachia and to her academic study of the region: “The education process must provide a true understanding of the history and exploitation of the area and a commitment to creative change. Education must be directed to changing the system by educating change agents and the resources of the colleges must be used constructively to attack real problems in the area . . .”4 Her philosophy of education embodies a commitment to creative change, and it was likely influenced by the citizenship schools that spread throughout African American communities in the South.

After a long struggle with university gender policies and a series of confrontations with powerful coal corporations in the local government and college, Lewis left formal academia in 1976 and continued her commitment to democratic education as a staff member at the Highlander Research and Education Center. This adult education center in New Market, Tennessee, fosters grassroots and social-justice organizing, and sociologist Aldon Morris characterized it as one of the Civil Rights “movement halfway houses” that inspired and nurtured participants. While at Highlander, Lewis showed special interest in local women’s involvement in community activism and was keenly aware of how poverty and sexism intertwine in Appalachian communities. Drawing on her experience with women’s cooperatives and economic education programs, she co-edited the handbook “Picking Up the Pieces: Women In and Out of Work in the Rural South.”5 Her two most recent books, It Comes From the People: Community Development and Local Theology (co-authored with Mary Ann Hinsdale and S. Maxine Waller) and Mountain Sisters: From Convent to Community in Appalachia (co-authored with Monica Appleby) evidence the pervasive Social Gospel discourse, although with a distinct Appalachian flavor that still permeates much of the progressive social activity in the region.

She sat down for this interview as part of the Southern Oral History Program’s “Women’s Movement Project,” a component of the SOHP’s research on the “Long Civil Rights Movement.”

What follows is Helen Matthews Lewis, in her own words:

Editor’s Note: Excerpts of Lewis’s interview follow. Access the complete article via Project Muse, or purchase Volume 17, Number 3, Fall 2011.

Growing up in Cumming, Georgia

When I moved to Forsyth County [at the age of ten, I] discovered that this was a county with no African Americans in the whole county. Some ten or fifteen years before, [local whites] had accused this Black [man] of raping a woman—one of those episodes—and they ran every Black out of the county, took over their farms and whatever they had. I was told stories about how they hung Blacks around the courthouse. I know they at least lynched the guy that they were accusing of this, and I don’t know how many others. Some people maybe have done some research on it, but the stories were told. I could just see bodies hanging all around the courthouse, in my mind as to what happened. So it was . . . horror. And then Blacks coming in through the town on trucks to deliver stuff to the stores were afraid to get out of the truck. They would hide in the back. I found this to be just horrifying, but somehow I never quite got it connected with doing anything about it or thinking about it in that way.

My father came home from the mail route one day, and he said he saw this old Black man bicycling through town and he was on his way to Gainesville. And he said, “I’m worried he’s got to go through Chestatee.” The young Chestatee boys were the ones that started the riot—the rowdy boys of Chestatee. They threw all the Blacks out. He said, “He’ll never make it to Gainesville.” So he gets in his car. “I’m going to go find him.” He goes and picks him up and takes him to Gainesville and comes back. So, there was that little bit of episode.

It was a real backwoods little town at that time. It was our first move to what I call “the mountains.” Now, Appalachia legally includes Jackson County, but we were more like hill country. The hillbillies lived up here, you know, more in the Blue Ridge area. When we got to Cumming there was a lot more country or mountain culture there, even though it’s just forty miles from Atlanta. In my classes [in the fifth grade] very few people had even been to Atlanta, and [our teachers] took us on a field trip. We’d go to the cyclorama and the zoo and see the city.

So it was quite a real country town. I mean, there were not even sidewalks. One year they did sidewalks and all the kids in town got skates—and it was not safe for anybody to walk on the sidewalks because we were all skating. We even skated in the middle of the highway, all the way up toward Dawsonville. Dawsonville was the moonshine capital of Georgia at that time, and all of these people, who became race car drivers, were running liquor every night down the only paved highway in north Georgia at that time, the road between Atlanta and Dahlonega, which came through Cumming. And the state police would be chasing these rum runners every night, so that was our sport, to say, “Oh, there goes Parker C.,” or “There goes—.” We knew them all by name, the drivers of the cars.

1942–1946: The Georgia State College for Women Campus YWCA and Interracial Organizing

After a year back at home I went to Georgia State College for Women, and there I became involved both with the Baptist Student Union and with the YWCA. The student YWCA was at that time pushing for integration—that was the mission of the student Y—and they would take you to integrated meetings and integrated conferences. They would have these conferences at Paine College, the Black college. So I got involved in going to integrated meetings. I spent a weekend at Atlanta University, living in a dormitory with Black students, and had some really interesting experiences, changing all my views. I didn’t have the real problem that other students did whose parents were real racists, because my father, even though he was not an activist, was this gentle, caring person, and they had no objections to my doing these things.

One summer another student and I did “Students-in-Industry” [a YWCA program to expose students to wage work, politics, and social life in urban centers] at Hartford Theological Seminary. We rode a Greyhound bus all the way from Atlanta to Hartford, Connecticut; it took three days to do it in those days. This was of course during the war and there were lots of problems with transportation and a lot of servicemen on the bus, and two nights you were on the bus. We all had to find jobs, and it was a great group. It was about eighteen of us. There was one Black student and one Japanese student, American Japanese, but he’d been in one of the concentration camps until that summer and then been released to go to MIT. We lived in this co-op house together and cooked together. The Black student was from Harvard and came from a very upper-class family who did not want him to participate, because there were going to be these two young girls from the South there, who they thought would mistreat their son. As it turned out he became one of our very best friends, and he and the Japanese guy and my friend and I hung out together the whole time and did all sorts of things together.

The Y at that time was a very important part of the whole college. The woman who was the Y secretary was on the staff, and they were given the job of doing the religious emphasis week—all the speakers for chapel—so they brought in all of these radical speakers, mostly from labor unions, and ministers who were really preaching social gospel, which was pretty radical. Then people like Clarence Jordan came, and he would do workshops. Frank McAllister from the CIO would come. Lucy Randolph Mason, who was this wonderful woman organizer, labor organizer—she would come speak. Everybody was part of the Y. Now later the schools got rid of the YWCA because it was so radical. It was really radicalizing students. Not everybody attended these things, but I just happened to be one of the ones that did. And the YWCA secretary had an apartment, a sort of open place, where we would go for breakfast and pancakes and discussion. And every speaker we had—afterwards, we would have meetings with them and ask questions and sit around on the floor.

academic work forged a connection between her region and the Civil Rights Movement. Harlem demonstrators in

support of the Selma’s Civil Rights marchers, 1965, photographed by Stanley Wolfson, courtesy of the New York

World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection at the Library of Congress.

Being Charged with Disorderly Conduct After Organizing and Attending an Interracial Meeting in 1948

In Atlanta, on the Emory campus, I take a job for the summer working with the YWCA. I am in the office, and we have this group of seminarians who come down to do service learning jobs. They’re staying out at the Black college, because there’s one Black student in the group. The Fellowship of Reconciliation [an international pacifist organization founded in 1914] was sponsoring them, and they asked the Y if we would have a little reception for them. I said, okay, good, and I’ll invite all these YWCA girls who are here for the summer. Some of them have just graduated—and they’ve got jobs—and one of them was working with the Girl Scouts and stuff. We had this reception for this group, and another Black couple comes with them. And the police raid us and arrest us for disorderly conduct and disturbing the peace.

They didn’t take us to jail. They pulled us out individually, and the policeman said to me, “What would your daddy think if he saw you dancing with a n****r?” We had been doing this little play party game, something like the Virginia reel [a folk dance] or something like that. Then they gave us all a ticket, and then we were to go to court. Well, the day we were to go to court the Klan marched against us, and [segregationist Georgia governor] Herman Talmadge was running this big newspaper, the Statesman, at that time. He jumped on the case, so we were getting too much publicity. Finally, we had a lawyer, James Mackay from Emory, and he got the disturbance of the peace, disorderly conduct, dismissed. Oh, it made the front pages of the Atlanta Constitution and the Atlanta Journal and listed everybody’s name and where they lived. Girls lost their housing. Some of them lost their jobs. Their families went into hysterics because [the newspapers] said “arrested at mixed dance.”

That was another experience which was important in my life.

The Women’s Movement

I’m part of the long women’s rights movement, I’d say. I remember when I was writing my thesis. I wanted to live in the 1830s and to have been at Seneca Falls. I really identified with all of those early abolitionist women. I just felt like that was where I should have been—that’s who I was—but I was in the 1940s and ’50s by then. So when the new women’s movement began, I fell right in. I think that I was one of those hanger-on-ers that kept something going, at least in myself, during the period when there wasn’t much of a movement. But I don’t think it ever completely disappeared. You can talk about the first wave, second wave, but [the Y and probably other women’s organizations] kept the movement going, maybe even some missionary societies. I don’t know. I know [you wouldn’t think] some of those literary clubs were progressive at all, but I bet you some of those tea parties had also led to some solidarity of women. They were like women’s support groups, if nothing else. And those 4-H Clubs and home demonstration clubs. My mother was part of a home demonstration club back in the ’20s and ’30s, and she even went to a conference at the University of Georgia and left my sister and me just with my father. That was really weird that she would do that, you know.

I’m part of the long women’s rights movement, I’d say. I remember when I was writing my thesis. I wanted to live in the 1830s and to have been at Seneca Falls. I really identified with all of those early abolitionist women.

But I think those home demonstration clubs were largely related [to a women’s movement]. Unfortunately, they got taken over by the electric power companies that were selling electric stoves and modernizing cooking and selling stuff. I think we need to really re-look at what was happening to women in that period, between what you would call the real suffrage movement and the vote, and when Betty Friedan and those people came forth. I think that we missed giving credit to some of those things that were happening. The YWCA was very deliberately working to promote women’s empowerment and things, but these others—probably, that wasn’t their mission. But I think they were filling a role that we’ve not understood fully.

There were really, really strong women in the ’30s.

There were really, really strong women in the ’30s. There was Eleanor Roosevelt. There was Frances Perkins [U.S. Secretary of Labor, 1933–1945]; there were role models. There were women that were very, very strong union organizers. Lucy Randolph Mason. There were all sorts of people at that period of time, and there was this group of women who helped organize and get Highlander going and who were union organizers.

But there was this real macho thing, and I guess your style of confrontation was—I don’t know if you’d call it more gentle or more subversive. I mean, you learned how to get around it without putting up your dukes. You catered to certain things, but then you just did what needed to be done—and maybe you had to pretend somebody else thought it up. Women have done that all their lives. If you judge the degree of authority that women [had to assume] against [their actual authority]—where you didn’t have that much in terms of legal position—[then] you worked in other ways. You could still make a difference.

The Highlander Folk School, the Civil Rights Movement, and Economic Education

I had heard about Highlander even when I was in college but had never been part of it, and, being in Appalachia during the really hot times of the Civil Rights Movement, we were too busy fighting the coal companies.6 I wasn’t at Selma, I didn’t walk across that bridge, I didn’t go for the Mississippi Summer, I was not involved. My Civil Rights stuff was early. It was in the ’40s, when people don’t know that there was anything going on. So I was [at Highlander] for the Appalachian period and on into the times when we were trying to pull together the Civil Rights South people and the Appalachian people—and that was the last phase—and then integrating in the new immigrants and the Spanish[-language] immigrants.

I was [at Highlander] for the Appalachian period and on into the times when we were trying to pull together the Civil Rights South people and the Appalachian people. . .

[Longtime southern activist Sue Thrasher] and I went up to [the University of Massachusetts at Amherst] and took that radical economics course that they have there in the summer. We checked out every program in the country, got all the syllabi together, and all of them didn’t really fit us. The Amherst thing was great for people who already had an economics major or were college educated, but it was not for ordinary country people with a seventh-grade education, even high school education. So we decided to go back to our form of education and see what we could do in terms of economic education based on [the] Highlander style of people learning from each other.

People are storytellers. People like to tell stories, so we developed a curriculum which could be used in some of these outreach programs. One of the things that I and other people were doing was develop little education programs, like in Dungannon, Virginia. We developed a GED program, and then we talked Mountain Empire Community College into offering some college courses there. They agreed to try out our little program, a class that we would have on learning your economic history. So we taught a class there, and [labor activist and historian] John Gaventa and I taught one at [the community center at Jellico, Tennessee] later.

It all grew out of our developing this thing where we start with oral histories, and what we start with is what did your grandparents do to make a living? And what did your parents do to make a living? And what do you do to make a living, and what does your generation make a living doing? And then we analyzed the history of the economy of this community and how it has changed, and you come up with actually a history of the economic changes in the United States, even with a small group of people. Even in these isolated places people have migrated out to get jobs, migrated in to get jobs, been involved in all the various changes that have occurred in the economy. Then we get to the point of What is our economy today? Where does the money come from? Who has the money?

What Inspired Her Activism

I think it had to do with principles of equality and fairness and justice, and where I got all of that. Part of it was through religion. Part of it was through my father, who was a very just, caring person, and my mother, who was a really hardworking, loving person. And things I read. I read about powerful women, strong women. I was a great admirer of Eleanor Roosevelt.

I felt I had to do it. There are certain things you have to do. You’re going to get in trouble, but that’s all right. [Highlander’s co-founder] Myles Horton always said, “You’re better known by the enemies you make.”

Jessica Wilkerson is an Assistant Professor of History and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. She earned her M.A. from Sarah Lawrence College and her Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is currently working on a forthcoming book, Where Movements Meet: From the War on Poverty to Grassroots Feminism in the Appalachian (University of Illinois Press) and is a Visiting Scholar at the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

David Cline is an Assistant Professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences at Virginia Tech. He received his M.A. from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and his Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He recently published From Reconciliation to Revolution: The Student Interracial Ministry, Liberal Christianity, and the Civil Rights Movement, 1960 to 1970 (University of North Carolina Press, 2016)

Header image: A selection of badges from women’s protest movements, from the Glasgow Women’s Library collection.NOTES

- The photograph was taken in 1966 while Lewis was doing research on coal mining safety for the Bureau of Mines. The smears of coal dust on her cheeks were applied after her first trip below ground as part of an initiation by local miners, mimicking the initiation male miners endured of being rolled in coal dust. Lewis was one of very few women allowed in a mine during this period. Prior to the lawsuits of the 1970s that opened up the industry, women were banned from entering mines because this was considered to bring bad luck. The custom was so rigidly enforced that during her work for the Bureau of Mines she was forced to employ male researchers to interview men in the mines, while she interviewed women and families above ground.

- See Helen M. Lewis, Linda Johnson, and Don Askins, eds., Colonialism in Modern America: The Appalachian Case (Boone, NC: Appalachian Consortium Press, 1978).

- Patricia Beaver, “An Interview with Helen Matthews Lewis,” Appalachian Journal 15 (Spring 1988): 238–65.

- “Appalachian Studies Programs: The General Philosophy Syllabus and Reading Lists,” Research and Activism Series, Curriculum Subseries, Folder 2, Academic Papers, 1972–1986, Box 1, Helen Lewis Matthews Papers, Collection 103A, W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University.

- Helen M. Lewis, Linda Selfridge, Juliet Merrifield, Sue Thrasher, Lillie Perry, and Carol Honeycutt, eds., “Picking Up the Pieces: Women In and Out of Work in the Rural South,” (New Market, TN: Highlander Research and Education Center, 1986).

- For more on the Highlander Center, see “I Train the People to Do Their Own Talking: Septima Clark and Women in the Civil Rights Movement,” edited by Katherine Mellen Charron and David P. Cline, Southern Cultures 16, no. 2 (Summer 2010): 31–52.