When Robert E. Lee met Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox in 1865, Grant introduced Lee to his personal military secretary, a man named Ely S. Parker. At first, the story goes, Lee refused to shake Parker’s hand, mistaking his darker complexion for that of an African American soldier in Union blue. But Parker was not black, he was Tonawanda Seneca, a member of the Iroquois Confederacy from New York; realizing his mistake, Lee stepped forward and offered his hand: “I am glad to see one real American here,” he said. Parker simply extended his hand and replied, “We are all Americans.”1

What did Lee mean by “American”? He invoked a definition of nationhood that the ancient Greeks and Romans and, later, the Nazis, also claimed: one was an American by virtue of one’s pure “blood” (a claim that one’s ancestors all belonged to the same “race”) and inalienable attachment to soil (or, the territory which white southerners, then and now, claimed they waged war to protect). Notably, some of the white supremacist groups at the August 2017 “Unite the Right” riot in Charlottesville, Virginia, chanted “blood and soil” as they protested the planned removal of Lee’s statue. Going back to before the Sons of Liberty at the Boston Tea Party, white Americans have used Indians to articulate their claims of righteous authenticity. This connection between “blood” and “soil” may be the reason Lee claimed a kind of affinity—however bitter—with Parker. By his own definition, Lee—obviously the descendant of immigrants—could not be an authentic American, except by erasing the land’s original inhabitants, one of whom was standing right in front of him. While black inequality was a cornerstone of the Confederacy, blood purity was not. In affirming his connection to a logic of blood and soil, Lee was rewriting history in his moment of surrender.2

But Parker’s riposte cleverly positioned Lee’s white supremacy as antithetical to the original values of the United States. Parker’s own Seneca ancestors had practiced adoption and a kind of naturalization of foreigners for centuries. As an Indian nation, they possessed their own definitions of belonging and extended those notions to include those who had tried to diminish—if not exterminate—the Seneca Nation. Their insistence on their sovereign ability to determine their own definitions of belonging and make alliances with new Americans is the very definition of independence upon which the United States was founded.

In the Civil War, American Indians like Ely S. Parker fought for themselves and their definitions of what it meant to belong. They are still fighting today to represent themselves on their own terms. They want their values enshrined in the nation’s public memory, but they want to control that representation. Parker’s encounter with Lee allows us to think about how we should embed American Indians within, rather than outside of, the Civil War; doing so reveals that American identity hinges on definitions of belonging that support white supremacy. As we see American Indians more clearly in the Civil War and its commemoration, the diverse stories of regions—South, North, and West—merge in a shared truth of the nation’s founding not only on independence and self-determination but on colonialism and its driving idea, imperialism.

How do American Indians remember and how are they remembered in American history? I begin this work from an understanding of myself as an American Indian—a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina—and a historian. We are always here, in the South, yet—as Robert E. Lee first thought of Ely S. Parker—folks figure we are also somehow away. That distance is enacted by historical events like the Trail of Tears or the process of writing our existence out of the popular story of the South, which has come to be dominated by the stories of black and white southerners and the twin pillars of the Civil War and civil rights. There are multiple explanations for this invisibility, be they physical removals, legal erasures, systemic obstacles, or commemorative acts that misremember or conflate our stories. These mechanisms to “forget” American Indians are not limited to one or another place within or away from the South, but they show how the South is part of the nation’s ongoing entanglement with colonialism.

We are always here, in the South, yet—as Robert E. Lee first thought of Ely S. Parker—folks figure we are also somehow away.

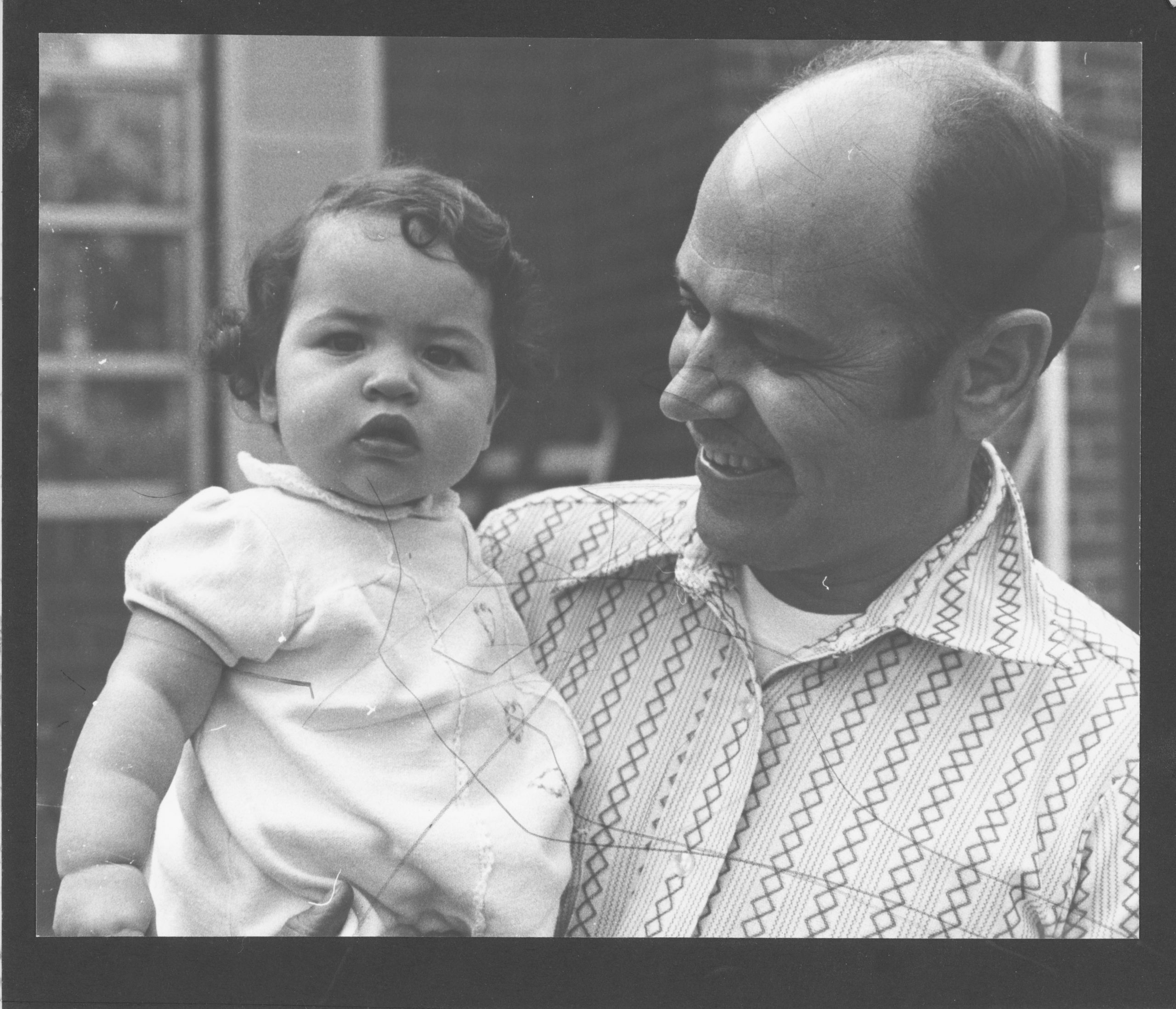

That invisibility shaped me from a young age as I absorbed my family’s stories; sometimes they emerged whole, but they mostly came as bits of information, puzzle pieces. They came in pieces not because the story is unknown, but because no one person knows the whole story. Researching and writing American Indian history is made even more interesting amid other southerners’—and Americans’—routine mourning over lost histories and lost causes. Growing up in North Carolina, outside of the Lumbee community but still connected to it, I’ve been conscious that my ancestors were the original southerners, that they were here before something called “the South” ever existed. Yet other Americans, especially southerners, freely mourn and memorialize their histories being lost or erased, all the while challenging our right as Lumbees to do the same. Instead, others look at the history we know perfectly well—if in pieces—and tell us we are not who we say we are, that we don’t have a history, that we are not important to U.S. history. Being left out of the history and the commemoration of the Civil War—one of the most important discussions in the South—is ironic, given that non-Indigenous Americans live on Indigenous land at all times. People like Robert E. Lee are in truth foreigners, even as every colonial government, including the United States, its sundry states, and, at one point, the Confederate States, has challenged the sovereignty of Indigenous nations.3

Being left out of the history and the commemoration of the Civil War—one of the most important discussions in the South—is ironic, given that non-Indigenous Americans live on Indigenous land at all times.

Indeed, the Civil War has its roots in settlers’ challenges to Indigenous authority. A set of Supreme Court decisions in the 1830s, part of Chief Justice John Marshall’s indelible influence on the laws that govern us today, allowed southern states like Georgia to challenge Cherokee sovereignty and expand the land available to white farmers for cotton agriculture and slavery. One of the rationalizations for Indian Removal was the cultural incompatibility of southern tribes and their white neighbors, even though a minority of these tribal citizens had become so thoroughly entrenched in the global economy that they themselves owned slaves. However, the federal and state governments colluded to force them to leave alongside the many more nonslaveholding tribal members, so that only whites could profit from cotton and slavery. Indian Removal undoubtedly contributed to the growth of slavery and the conditions that caused the Civil War.

Tribes who remained east of the Mississippi, like my ancestors, approached the war with ambivalence and took different approaches. Indian communities who remained after Removal rejected slaveholding, though Eastern Band Cherokees formed a Confederate Army regiment. After Removal, many state laws legally grouped some Indians with freed black Americans, especially if those Indians did not live on reservation land. Accordingly, sometimes the two groups took up the same causes, and sometimes they didn’t. African Americans and Native people in New England both fought for the Union, while members of both groups resisted the Confederacy in southeastern North Carolina.4

My great-great-great-grandfather Thomas Sanderson enlisted in the Confederate Army in 1862; a few months later, he faced one of the unquestionable horrors of the Civil War—the Battle of Antietam. Antietam was considered by some the bloodiest day in American history, with twenty-three thousand Union and Confederate casualties. Afterward, General Lee’s Confederate Army escaped unpursued by Union troops, and my three-times great-grandfather was with them. A few months later, he was promoted to corporal, and then, less than a year later, to full sergeant. He died at age eighty-seven in 1920.5

Though I was raised to be proud of my southern roots, I knew nothing about this Confederate ancestor until I began research for my most recent book. My Confederate ancestor is buried at what we call the Sandcutt Cemetery in Pembroke, North Carolina, resting place of many of my ancestors. There he has two tombstones, one that marks his Confederate service and one that doesn’t. Though I have seen his grave markers many times, it never occurred to me to ask about his Confederate service. As a young person growing up Lumbee in North Carolina, the Confederacy was everywhere—like wallpaper—but had little to do with my southern identity, and even less to do with my southern pride. In fact, my sense of myself as a Lumbee and a southerner was defined more heavily by my other ancestors’ resistance to the Confederacy.

The rest of my own Lumbee family tree is populated by people who remained loyal to the Union. Their rebellion was known as the “Lowrie War,” following the name of its ringleader, Henry Berry Lowrie. Starting in late 1864, he and a gang of Indian, black, and white North Carolinians killed a score of former Confederates, including a rumored Ku Klux Klan leader. The murder of Henry Berry’s father and brother, men whose loyalty to the Union was well known, escalated the killings, but this was more than a vengeful murder spree. The political implications were obvious. Lumbees on the whole remained so loyal to the Union that when Radical Republicans gained control of local government after the war, they came courting Lumbee voters. Yet, Republican authorities executed my great-great-grandfather Henderson Oxendine for his membership in the Lowrie gang. He died in 1871 at age twenty-seven. His tombstone, the luckstones, and then the grave marker—installed by my uncle—are what I grew up understanding as memorials to those who died in war. My family never mentioned Thomas Sanderson’s Confederate service because his sacrifice did not represent the values they wanted me to adopt. They did teach me to value Henderson Oxendine’s service in a very different kind of war.6

A second connection between Indians and the Civil War emerges when we look more closely at western expansion. American Indians often confronted both the North and South as hostile actors. Slave owners were in the extreme minority among tribal members who traveled the Trail of Tears, but in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) they represented enough wealth and power that, when the Civil War arrived, the Confederacy sought their allegiance and resorted to virtual extortion to secure it. Meanwhile, during the Civil War in Minnesota, the Union furthered the quest for “Manifest Destiny” by killing Dakota Sioux soldiers in the largest public execution in American history. In Arizona and New Mexico, the Union Army forced Diné (Navajo) men, women, and children to march eight hundred miles from their homelands to an internment camp. While we think of the Civil War as a war of the South, to free the slaves, it was also a war of the West—in its conflicts with American Indians, the Union Army united white Americans and provided them with places to profit from their labor.7

The end of the Civil War aggravated the tensions between American Indian and federal authority in the West. In 1868, having lost a series of battles to Lakota Sioux armies, the United States signed a treaty with Native leaders that reserved sixty million acres to be controlled by the Sioux and other tribes. William Tecumseh Sherman, the Union general responsible for the scorched-earth strategy that defeated the Confederacy, negotiated the treaty with Native leaders. Key to the treaty was Lakota control over the Black Hills, including the mountain known as “Six Grandfathers,” where Mount Rushmore is today. But following a series of events that included General Custer’s discovery of gold in the 1870s in the Black Hills and the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890, the U.S. reneged and seized almost all the land that had been returned to the tribes under the treaty. The Confederacy’s commitment to slavery and the Union’s commitment to expansion are different versions of the same story of colonialism and imperialism. At the end of the day, American Indians had little reason to trust either side.8

Accordingly, representations of Indians in the South and the West in public monuments are distorted. Confederate statues generally exclude Indians completely (though a monument to Catawba Confederate soldiers exists in Fort Mill, South Carolina). So-called “pioneer monuments” populate the Midwest and West. Like the Confederate monuments, these pioneer monuments on one level represent something accurate—in this case, the exploration or settlement of the West. There is a pattern in their depictions—white men and women, often with children, are the primary focus. Similar to Confederate monuments, all is not what it seems. What we know about western settlement—that it involved people of many nationalities, that conquest (not just settlement) was the intent of these migrations and their effect—is not always marked in these statues. When it is, Native people are there to represent values that outsiders impose upon them, as opposed to their actual, complex roles in this history.9

Pioneer monuments in the West also compromise historical fact in favor of a conquest myth that diminishes American Indians. The “Early Days” statue in San Francisco is one example. Installed on Thanksgiving Day in 1894, Early Days belonged to a set of monuments dedicated to the settlement of California. Unlike many other pioneer monuments, which feature only European Americans, Early Days does gesture toward a multiethnic, diverse California—the intent is to portray a Mexican vaquero, a Spanish monk, and an Indian. But it relies on visual stereotypes, including a figure of a generic Plains Indian, with nothing to mark the person as an Ohlone Indian, the community that then and now calls the Bay Area home. The statue also venerates the subjugation of Indians. The vaquero stares into the future, his hand raised in triumph; behind him, a monk points to heaven with one finger and with the other hand appears to have just shoved the Native man down, who is sitting on the ground and covered only in a blanket. In this way, it accurately portrays white Californians’ views of their settlement of the West, if not Indian responses. The statue was dedicated just four years after the U.S. Army massacred Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee in South Dakota; white Californians used the monument to mark how converting Indians, even committing genocide against them, was not only necessary but morally correct. The position of the clothed monk and the nearly naked Indian, in particular, emphasizes this moral superiority of one civilization over another. As historian Rebecca Solnit points out, the images of the vaquero and the monk are gesturing upward, as their space expands, while that of the Indian submits and contracts.10

Protest against the statue’s presence goes back to at least 1991 and, in 1995, the American Indian Movement wrote a letter to the city requesting removal “of a monument that symbolizes the humiliation, degradation, genocide and sorrow inflicted upon this country’s Indigenous people by a foreign invader.” For some, genocide seems like an inflammatory, politicized accusation, contrary to every value the United States holds. And indeed, historians have debated for some time whether genocide could be appropriately applied to Native history. But as a recent book by historian Benjamin Madley details, genocide was the expressed intent of both the California state and federal governments in the nineteenth century—their preferred way of dealing with Indians. When the California governor told the newly elected state legislature in 1851 “that a war of extermination would continue to be waged until the Indian race should become extinct,” genocide was certainly an articulated policy. Many believe that the release of Madley’s book in 2016 finally swayed the city of San Francisco to remove the statue in September 2018, but an attorney from elsewhere in the state has filed suit to put it back. He claimed that the city did not follow standard procedures to remove the monument and that its removal was equivalent to the Nazi’s or Taliban’s destruction of art.11

Confederate monuments and pioneer monuments are both anachronistic symbols masquerading as truth. Both purport to honor heroism, individualism, and sacrifice, but they also disguise value systems that sustain racial hierarchies and the idea of cultural supremacy. Confederate monuments were not built immediately after the war but largely during Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement. Although they were often called memorials to the dead, they were built to express white southerners’ objections to black equality. For example, at the ceremony to dedicate “Silent Sam,” the monument that stood on UNC-Chapel Hill’s campus, the keynote speaker—a donor, industrialist, and Confederate veteran named Julian Carr—made false claims about the war. His speech praised Confederate soldiers for defending the purity of the Anglo-Saxon race, but the white South’s emphasis on racial purity did not emerge until after the war. Slavery—the issue over which the war was fought—did not need racial purity to grow and thrive, but racial purity did become a foundational principle of Confederate memory, just as white supremacy remained a cornerstone of both regimes. Carr went on to describe his commitment to white supremacy in very personal terms. Shortly after his return from Appomattox, Carr said, he “horse-whipped a negro wench” only one hundred yards from the statue on the “quiet” streets of Chapel Hill because the woman had reportedly “insulted and maligned” a “Southern Lady.” Carr’s audience knew the kind of “southern lady” to which he referred—not women like me.12

Confederate monuments and pioneer monuments are both anachronistic symbols masquerading as truth.

American Indians—alongside African Americans—faced the realities of living under a regime that was rewriting its own history. Jim Crow was not a natural outgrowth of slavery. Black Americans (and, in the South, many American Indians) used the Civil War and Reconstruction to fight for a political voice that became very powerful. Following emancipation, it took a widespread counterrevolution—political coups, election fraud, lynchings, and then segregation laws upheld by the Supreme Court—for white Americans to reestablish their control. In Oklahoma, a howling mob burned two Seminole teenagers alive in 1898; their ostensible crime was the murder of a white woman, but in fact, white neighbors targeted them because of personal grudges and long-simmering land disputes.13

Most Indians in the South had little contact with the federal government through the Jim Crow years as whites’ violent counterrevolution settled into peculiar customs. Indians navigated these customs too, and their very existence belied whites’ insistence that there were two races, never to be mixed. My parents, both Lumbees, went to segregated Lumbee-only schools. Fueled by the betrayals of Reconstruction, the Lumbees turned Jim Crow into an opportunity to establish the University of North Carolina at Pembroke in 1887, the oldest college founded by and for American Indians in the United States.14

The Confederate “Lost Cause” and the logic of racial separation that went with it had real policy implications, with a particular intent to erase Indians who troubled white supremacy’s racial assumptions. For example, in 1924, the Virginia legislature passed the Racial Integrity Act; it outlawed interracial marriage, in part by reclassifying American Indians as “colored.” A Virginia doctor led the effort; like the Nazis then coming to power in Germany, he believed that biologically inferior children emerged from racial mixing. In the interest of public health, anyone with “one drop” of nonwhite blood should not be able to marry a white person. State governments throughout the nation agreed and forcibly sterilized Indian, black, and poor white women thought to possess these “polluted” genes.15

At this same time, groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy literally rewrote history. Heritage groups and school curricula ignored evidence for the true causes of the war. Instead, school children learned that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights and that to be enslaved was to be happy. In the meantime, Indians vanished from history and were reincarnated as everyone’s full-blooded Cherokee princess great-grandmother. Driven by this commitment to distorting the past for white Americans’ benefit, Confederate monuments began appearing in cities, towns, and college campuses.16

Monuments like Silent Sam have received an enormous amount of attention, especially since riots in Charlottesville, Virginia, resulted in the death of one woman, Heather Heyer, and dozens of injuries over the fate of that city’s monuments to Confederate generals. These events in Charlottesville ignited recent discussions about what to do with Confederate monuments.

Another kind of statue also stands in Charlottesville—a monument to western exploration that takes the form of Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and Sacagawea. Both Lewis and Clark were born in Virginia. Dedicated in 1920, Charlottesville’s tourism bureau website states that the sculpture “expresses the popular sentiments of the day towards the general themes of exploration, national purpose and conquest of the wilderness of North America.” On its website, the state library of Virginia encourages educators to use the monument to ask, “Imagine you are going on this expedition with Lewis and Clark, what resources will you use to research the new American territory and to report your findings to President Thomas Jefferson?” These queries about the monument might encourage interesting questions about American Indian history that can’t be addressed with other readily available source material, but they conceal Sacagawea’s role—even though she is in plain sight. Instead, they encourage us to see American bravery and Indian subservience. Indeed, the monument itself seems to acknowledge but diminish Sacagawea’s role; she is huddled over, positioned behind Lewis and Clark. Her gaze is directed downwards, while the two men stand tall, looking towards the horizon. Who is conquering and who is conquered seems clear in this work of public art. In her crouched position relative to the two men, Sacagawea is literally bearing the burden of conquest on her back.17

As with the Confederate monuments in Charlottesville, this one has received thoughtful engagement from city residents, many of whom advocate for greater context for or removal of the statue altogether. Going back to 2007, citizens have identified the problem with Sacagawea’s shrinking stance in this monument. In 2009, the city installed a plaque that focused on Sacagawea’s contribution, written by descendants of her family. Members of the Monacan Nation, a tribe that has called Virginia home for ten thousand years, participated in the ceremony.18

Interestingly, when the coalition organized to oppose the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in August 2017, they did not invite any representatives of Virginia’s seven American Indian tribes to participate. When asked about his tribe’s exclusion from the Charlottesville protests, Monacan Nation Chief Dean Branham said, “We wouldn’t have been involved with it anyway. I don’t have any problem with those statues . . . I just don’t think it’s an Indian issue.”19

His comment reflects frustration with a variety of forces, including the forces of Jim Crow—how the state imposed inaccurate racial categories on Virginia Indians and Indians’ erasure from public records and community narratives. The “Indian issues” that Chief Branham deals with include how to protect their lands from energy developers, how to promote economic development, how to provide health and education for Monacan people, and how to obtain, after ten thousand years of continuous occupation, the federal government’s acknowledgement of the Monacan as a sovereign nation (finally resolved in February 2018).20

While Indians have been largely absent from Confederate commemoration in the South, white southerners have found other uses for their stories. In the words of historian Andrew Denson, southerners have created “monuments to absence”; his book by that very name chronicles the many southern monuments to Indian Removal, or the Trail of Tears. These monuments to the Trail of Tears exist in a variety of forms—from plays and historical sites to statues and signs. They largely commemorate the disappearance of Indians from those places.21

These monuments, too, have a moral message. Many of them were constructed during the most heated phase of the Civil Rights Movement. For example, beginning in the 1950s, the Georgia Historical Commission rebuilt the town of New Echota, which had been the Cherokee Nation’s capital before Removal. They had the full support of segregationist governors and legislators, and, when the site was completed in 1962, speakers at the ceremony specifically apologized for Removal. The moral message of this historic site, according to Andrew Den-son, was atonement, an admission of guilt by white Georgians for crimes against now-absent Cherokees. Denson wrote, “Georgia dedicated New Echota while elsewhere in the state civil rights activists fought the Albany campaign, maintained a bus boycott in Macon, and worked for desegregation of public facilities in Atlanta.” But expressions of white guilt about Removal inspired no controversy, even as these same politicians fought against black equality.22

According to Denson, “The story told at New Echota bore striking similarities to the myth of the Confederate Lost Cause in southern memory culture.” The site portrayed the Cherokee Nation as a peaceful, productive people invaded by outsiders, not that different from the language of the 1956 Southern Manifesto, a document signed by southern congressmen that decried the overreach of federal power into their states’ right to maintain segregated schools. As the Sons of Liberty had done, southern congressmen claimed an Indigenous story of federal overreach for themselves, attempting to create common cause with Indians who their political forebears had exiled to make way for their own economic self-interest. When their dedication to slavery led to war and destruction of the pitiable “southern way of life,” the memory of the Lost Cause led white southerners to apologize for their ancestors’ role in Indian Removal. At the same time, they fiercely opposed integration; unlike Indians, black Georgians were still very much present. The commemoration of Cherokee Removal provided an opportunity for white politicians to appear remorseful about race relations while doing nothing to atone for their treatment of blacks. The old justifications for Confederate secession found new life in massive resistance to the Civil Rights Movement, and commemoration of Indian absence in Georgia helped white Georgians cover for their case against black equality.23

Georgia is also home to an utterly unique Confederate monument that rivals only Mount Rushmore in its permanence and impact. The carvings at Stone Mountain were initiated around the same time that most southern cities installed Confederate monuments. Stone Mountain itself had hosted the modern revival of the Ku Klux Klan at a rally and cross-burning on Thanksgiving in 1915. A year later, the mountain’s owner, an active Klan member, deeded the north face to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which began planning an elaborate bas-relief carving on the mountain. Their vision involved an enormous portrayal of Confederate soldiers riding with Klan members. The first sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, began the project but World War I arrived and funds were tight, so, instead, Borglum settled on Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, along with Confederate President Jefferson Davis. But after a year spent only carving Lee’s head, Borglum was fired from the project and it took decades—and public funds—to complete the monument. Stone Mountain became a state park in 1958 “as a memorial to the Confederacy,” according to a newspaper. The writer might have added “and a backlash to the Civil Rights Movement.”24

According to one source, Borglum was fired because the creators of Mount Rushmore offered him their job. He spent the last sixteen years of his life working in South Dakota on a monument that, at first, seems like a tribute to American democracy. But it is also a monument to western expansion and a fantasy about the disappearance of Indians from public life. Borglum was obsessed with colossal works that would survive geologic time scales, but it also seems that he was obsessed with white supremacy. He had no ties to the Confederacy but had strong views on sustaining the purity of the white race. He wrote in letters that he feared a “mongrel horde” would overrun “the ‘Nordic’ purity of the West.” According to Smithsonian magazine, he once said, “I would not trust an Indian, off-hand, 9 out of 10 [times], where I would not trust a white man 1 out of 10.”25

But aside from Borglum’s involvement, Mount Rushmore holds a deeper message. The National Park Service claims that visitors are witnessing “a rich heritage we all share,” but the claim on that heritage is much deeper for Indigenous people. The Black Hills are specifically sacred to these tribes, a site of creation and renewal where ceremonies are conducted. In the words of one journalist, “The Lakota and others say that Mount Rushmore isn’t just a piece of art they dislike; it’s a piece of art they dislike that, to put it in European terms, has been forcibly installed in their own church.” In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed that the Lakotas were entitled to a $1 billion settlement for the government’s theft following the 1868 treaty, but Lakota nations have refused to take the money—they want the land. American Indian leaders from across the country, not just those from the tribes most affected, have rejected Mount Rushmore since the late 1960s.26

Many people who object to removing or contextualizing these memorials say that doing so is erasing history. Whose history? What process should we use to agree on which history we remember? These folks have nothing to fear; the nation’s history of white supremacy has been enshrined in treaties, laws, and policies; it cannot be erased. These monuments have become symbolic ways to venerate those laws. Black Americans and American Indians are southerners too, and their histories deserve to be remembered. Understanding the correct history—and the impact of false narratives on those most damaged by this history—must be the first step to a more inclusive public memory.

Many people who object to removing or contextualizing these memorials say that doing so is erasing history. Whose history? What process should we use to agree on which history we remember?

Native people are consistently engaged in their own commemoration practices. In North Carolina, Lumbees are seeking acknowledgement of their efforts to fight racial injustice and renaming places considered important to them. The Lowrie War, in which my great-great-grandfather Henderson Oxendine fought and died, had no public markers until 2016, when the state historical commission finally settled upon text that would be suitably neutral. According to an archivist who works closely with the highway marker program, citizens had been petitioning to place a marker for Henry Berry Lowrie since the 1970s, but the committee could not agree on whether to honor such a notorious outlaw. Jefferson Davis, however, has four markers. Perhaps one of the Jefferson Davis markers should say that he was the only outlaw in North Carolina history with a bounty that was higher than Henry Berry Lowrie’s.27

The 452-mile-segment of Interstate 74 that runs through North Carolina, including Henry Berry Lowrie’s homeland, was named the “Andrew Jackson Highway” in 1963. Imagine Ku Klux Klan Boulevard running alongside Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, where—also in 1963—the Klan killed four black girls in a firebombing. It indicates the nation’s investment in white supremacy that an east-west highway which begins at Chattanooga, Tennessee, once a key location of Cherokee government and education, should be named for the person arguably most responsible for their forced Removal. Jackson was arguably born in the western part of North Carolina, close enough to the South Carolina border that either state might claim him. In April 1963—six months before the March on Washington and seven months before the Birmingham bombing—North Carolina lawmakers staked their claim on Jackson’s legacy by naming the highway after him. In 2015, Lumbees finally secured a name change. That year, North Carolina’s only Lumbee representative to the state General Assembly pushed for a law renaming nineteen of the 452 miles the “American Indian Highway.” Each time I drive that stretch of road I feel relieved not to see Andrew Jackson’s name there.28

Just recently, another episode in the southern struggle for equality became part of North Carolina’s public memory. In 2018, the state erected another highway marker, this time commemorating the Lumbees’ defeat of the Ku Klux Klan in 1958. In January of that year, the Klan terrorized two Lumbee families who had broken the segregation barrier—they burned a cross on the lawn of a Lumbee woman who was dating a white man, and another on the lawn of a Lumbee family who had moved into a white neighborhood. A few weeks later, the Klan Grand Dragon, a man known as Catfish Cole, announced a public rally not far from the soon-to-be-named Andrew Jackson Highway. That night, about fifty Klan members drove to Hayes Pond and circled their cars; Cole set up a small generator, a pa system, and a lamp. Most of Robeson County’s Klan members stayed home; the fifty Klan members, women, and children at the rally were part of Cole’s following from South Carolina. Soon they were surrounded by five hundred Indian men, many of whom were veterans; and about fifty Indian women. The group was armed with rifles, shotguns, pistols, and knives.29

When Cole began to speak, the Indian crowd erupted, firing guns into the air and roaring. Cole took off running into the swamps. His panicked followers dropped their guns, jumped in their cars, and drove in all directions, some straight into the ditches that surrounded the field. Miraculously, no one was seriously injured. Cole didn’t come out of his hiding place for two days.30

American Indians have their own ideas about public memory and the visibility that accompanies it. Today, 32 percent of the United States’s American Indian population lives in the South. We’re hardly invisible, but, like the monuments that are everywhere in our midst, one has to listen more carefully and look beneath the surface. Some Native people, such as Monacan Nation leader Dean Branham, believe that their path to recognition lies outside the work of wrestling with white supremacy through public commemoration. They wrestle with the ways in which white supremacy is embedded in federal Indian policies, policies which are founded on imperialist ideas and enacted largely, though not exclusively, through western expansion and colonialism. In contrast, when faced with expressions of white dominance, the Lumbees seek to use public memory to expand the definition of American belonging, much as Ely S. Parker did when faced with Robert E. Lee’s revision of history. As we look deeper, American Indians, both in the South and the West, clarify something that is often clouded in the field of southern studies: the indelible connection between the South and the nation; and the embedded nature of American Indian history within United States history.31

This article appeared in the “Here/Away” Issue (vol. 25, no. 4: Winter 2019).

MALINDA MAYNOR LOWERY is a professor of history at UNC-Chapel Hill and directs the Center for the Study of the American South. She is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. Her second book, The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle, was published by UNC Press in 2018. She has written articles and essays on topics including American Indian migration and identity, school desegregation, federal recognition, religious music, and foodways.NOTES

- C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa, Crooked Paths to Allotment: The Fight over Federal Indian Policy after the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 1.

- Rebecca Futo Kennedy, “Blood and Soil from Antiquity to Charlottesville: A Short Primer,” Classics at the Intersections, August 17, 2017, https://rfkclassics.blogspot.com/2017/08/blood-and-soilfrom-antiquity-to.html. For more on white Americans’ appropriation of indigeneity, see Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999); and Jean M. O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England, Indigenous Americas Series (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). On black inferiority as a cornerstone of the Confederacy, see Henry Cleveland, Alexander H. Stephens, in Public and Private. With Letters and Speeches, Before, during, and Since the War (Philadelphia: National Publishing, 1886), 721; and “Document: ‘Cornerstone’ Speech,” Teaching American History, accessed August 1, 2015, http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/cornerstone-speech/.

- For more on the contested nature of American Indian sovereignty, see Kevin Bruyneel, The Third Space of Sovereignty: The Postcolonial Politics of U.S.–Indigenous Relations, Indigenous Americas Series (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); and Valerie Lambert, Choctaw Nation: A Story of American Indian Resurgence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009).

- See for instance, William McKee Evans, To Die Game: The Story of the Lowry Band, Indian Guerrillas of Reconstruction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971); E. Stanly Godbold Jr. and Mattie U. Russell, Confederate Colonel and Cherokee Chief: The Life of William Holland Thomas (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990); and Laurence M. Hauptman, Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War (New York: Free Press, 1995), chaps. 4 and 6.

- “Casualties of Battle,” Antietam National Battlefield Maryland, National Park Service, last modified December 30, 2015, https://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/casualties.htm; “Thomas Beauregard Sanderson,” Find A Grave, May 2, 2012, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/89495962/thomas-beauregard-sanderson; “Thomas Sanderson,” Find A Grave, May 11, 2012, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/90002092/thomas-sanderson; “Confederate Regiment: 46th North Carolina Infantry,” Antietam on the Web, accessed November 20, 2018, http://antietam.aotw.org/officers.php?unit_id=671&from=results; Jane Blanks Barnhill, “Sandcutt Cemetery,” Cemetery Entries Beginning with R and S, RootsWeb, accessed April 30, 2018, http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ncrobcem/RandS.html; “SR State Auditor 1901 Pensions, 5 22 375 43 Sanderson Thomas Robeson County 001,” North Carolina Digital Collections, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, accessed November 1, 2018, http://digital.ncdcr.gov/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16062coll21/id/127928/rec/11.

- “The Death Penalty—Execution of Henderson Oxendine,” Carolina Farmer and Weekly Star (Wilmington, NC), March 24, 1871; “Trial of Oxendine,” Daily Journal (Wilmington, NC), March 11, 1871. Historical documents of the mid-nineteenth century spelled the surname of Henry Berry’s family as “Lowrie,” though members of the community today spell the name “Lowry” or “Lowery.” Contemporary historians of the period, such as William McKee Evans, often use the contemporary spelling.

- Mary Jane Warde, When the Wolf Came: The Civil War and the Indian Territory, The Civil War in the West (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2013); Hauptman, Between Two Fires, chap. 3; “The U.S.–Dakota War of 1862,” Minnesota Historical Society, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.usdakotawar.org; “The Long Walk,” Peoples of the Mesa Verde Region, Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, accessed May 1, 2018, http://www.crowcanyon.org/educationproducts/peoples_mesa_verde/historic_long_walk.asp. For more on American Indians in the Civil War and the federal government’s approach to Indian policy during the war, see Rose Stremlau, C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa, and Malinda Maynor Lowery, “Native Americans in the Civil War,” The Essential Civil War Curriculum, Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech, April 2018, https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/native-americans-in-the-civil-war.html. Ari Kelman’s forthcoming book, For Liberty and Empire: How the Civil War Bled into the Indian Wars, explains that Union losses to the Confederacy in 1862 led Lincoln’s administration to reallocate resources to the Dakota War, which helped secure a Union victory in that conflict. Likewise, the Emancipation Proclamation was designed to secure Union victory; it freed remarkably few slaves. As detailed in Lincoln’s Proclamation: Emancipation Reconsidered, emancipation was designed to secure the loyalty of border states to the Union and strengthen its military, a strategy that ensured free white men would maintain control of land in the South and the West. The proclamation’s ability to empower black Americans was limited to those black soldiers it authorized to enlist in the Union Army, some of whom later served in wars against Native people in the West. See William A. Blair and Karen Fisher Younger, eds., Lincoln’s Proclamation: Emancipation Reconsidered (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009). William H. Leckie and Shirley A. Leckie, The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Black Cavalry in the West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003).

- “Treaty with the Sioux-Brulé, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, San Arcs, and Santee—and Arapaho,” April 29, 1868, RG 11, General Records of the United States Government, National Archives; “Transcript of Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868),” Our Documents, accessed November 1, 2018, https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=-false&doc=42&page=transcript; Edward Lazarus, Black Hills / White Justice: The Sioux Nation Versus the United States, 1775 to the Present (New York: HarperCollins, 1991).

- “Pioneer Monuments,” Pioneer Monuments in the American West, accessed November 1, 2018, https://pioneermonuments.net/. For more on Indians in public monuments, see Denise D. Meringolo, Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012); Lisa Blee and Jean M. O’Brien, Monumental Mobility: The Memory Work of Massasoit (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019); Erika Doss, Monumental Mania: Public Feeling in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012); David W. Grua, Surviving Wounded Knee: The Lakotas and the Politics of Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); Catherine W. Bishir, “Landmarks of Power: Building a Southern Past, 1885–1915,” Southern Cultures 1 (1993): 5–45; and Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

- “Lick Pioneer Monument,” Pioneer Monuments in the American West, accessed November 1, 2018, https://pioneermonuments.net/highlighted-monuments/san-francisco/lick-pioneer/; “Civic Center–Pioneer Monument,” Public Art and Architecture from Around the World, January 27, 2012, https://www.artandarchitecture-sf.com/civic-center-san-francisco-january-27-2012.html; Dominic Fracassa, “SF’s Controversial ‘Early Days’ Statue Taken Down before Sunrise,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 14, 2018, https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/Controversial-S-F-Early-Days-statue-taken-13229418.php; Daniela Blei, “San Francisco’s ‘Early Days’ Statue Is Gone. Now Comes the Work of Activating Real History,” Smithsonian, October 4, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/san-francisco-early-days-statue-gone-nowcomes-work-activating-real-history-180970462/; Jose Fermoso, “A 124-Year-Old Statue Reviled by Native Americans—And How It Came Down,” Guardian (U.S. edition), September 24, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/sep/24/early-days-statue-removed-san-francisco-native-americans; Rebecca Solnit, Storming the Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 41–42.

- Solnit, Gates of Paradise, 42; Michael J. Ybarra, “San Francisco Journal; A Monument Caught in the Middle,” New York Times, May 7, 1996, https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/07/us/san-franciscojournal-a-monument-caught-in-the-middle.html; “Lick Pioneer Monument”; Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016); Blei, “‘Early Days’”; governor quoted in Solnit, Gates of Paradise, 44; Fracassa, “Statue Taken Down.”

- Bishir, “Landmarks of Power”; Savage, Standing Soldiers; James L. Leloudis and Cecelia Moore, “Silent Sam: The Confederate Monument at the University of North Carolina,” accessed November 22, 2018, https://spark.adobe.com/page/Z4gHJKurmmkZS/. For more on the maintenance of white supremacy without racial purity, see Cheryl I. Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Harvard Law Review 106, no. 8 (June 1993): 1707–1791; and Julian Carr, “Unveiling of Confederate Monument at University,” UNC Libraries, accessed November 22, 2018, https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/items/show/5519.

- Daniel F. Littlefield Jr., Seminole Burning: A Story of Racial Vengeance (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996).

- Malinda Maynor Lowery, Lumbee Indians in the Jim Crow South: Race, Identity, and the Making of a Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); David K. Eliades, Lawrence T. Locklear, and Linda E. Oxendine, Hail to UNCP! A 125-Year History of the University of North Carolina at Pembroke (Chapel Hill, NC: Chapel Hill, 2014).

- Arica L. Coleman, That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans, and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013); Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996); Joshua A. Krisch, “When Racism Was a Science,” New York Times, October 13, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/14/science/haunted-files-the-eugenics-record-officerecreates-a-dark-time-in-a-laboratorys-past.html.

- Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003).

- “Lewis and Clark and Sacagawea Statue,” Charlottesville, Albemarle County, Virginia, Visit Charlottesville, accessed November 8, 2018, https://www.visitcharlottesville.org/listing/lewis-%26-clark-and-sacagawea-statue/573/; Allison Cintins, “Sacagawea Statue: Tracking or Cowering?” C-VILLE, November 13, 2007, http://www.c-ville.com/Sacagawea_statue_Tracking_or_cowering/#.W_3yuXpKgWo; “Monument Dedicated to Lewis and Clark, 1939,” Document Bank of Virginia, Library of Virginia, accessed November 8, 2018, http://edu.lva.virginia.gov/dbva/items/show/166.

- “Mayor Walker: Remove Lewis and Clark Statue as Part of Any West Main Renovation,” NewsRadio WINA, accessed November 8, 2018, https://wina.com/news/064460-mayor-walker-remove-lewisclark-statue-as-part-of-any-west-main-renovation/; David McNair, “Loo-loo Cry: Sacajawea Gets a Plaque,” Hook, June 19, 2009, http://www.readthehook.com/71039/loo-loo-cry-sacajawea-getsplaque; Samantha Baars, “Controversy Resurfaces: Should the Statue Stand?,” C-VILLE, March 3, 2016, http://www.c-ville.com/controversy-resurfaces-statue-stand/#.W_Yc23pKgWr.

- John Last, “No Invitation: Why Native American Groups Weren’t Protesting Unite the Right,” C-VILLE, September 20, 2017, http://www.c-ville.com/native-american/#.WeEuutOGORs.

- Erin O’Hare, “After Inhabiting Virginia Land for 10,000 Years, the Monacan Indian Nation Finally Receives Federal Recognition,” C-VILLE, March 9, 2018, http://www.c-ville.com/inhabiting-virginia-land-10000-years-monacan-indian-nation-finally-recevies-federal-recognition/#.Wu831dPwbBJ.

- Andrew Denson, Monuments to Absence: Cherokee Removal and the Contest over Southern Memory (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

- Andrew Denson, “Remembering Cherokee Removal in Civil Rights–Era Georgia,” Southern Cultures 14, no. 4 (Winter 2008): 89, 92.

- Denson, “Cherokee Removal,” 96; “Declaration of Constitutional Principles [The Southern Manifesto],” March 12, 1956, http://alvaradohistory.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/4Southern-Manifesto.1134251.pdf; see also “The Southern Manifesto of 1956,” History, Art and Archives, United States House of Representatives, accessed June 24, 2019, https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1951-2000/The-Southern-Manifesto-of-1956/; and Denson, “Cherokee Removal,” 96.

- Bruce E. Stewart, “Stone Mountain,” Geography and Environment, New Georgia Encyclopedia, May 25, 2004, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/geography-environment/stone-mountain; Debra McKinney, “Stone Mountain: A Monumental Dilemma,” Southern Poverty Law Center, February 10, 2018, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2018/stone-mountain-monumental-dilemma; Wikipedia, s.v. “Stone Mountain,” last modified May 9, 2019, 16:41, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stone_Mountain#Confederate_Memorial_controversy.

- Adam J. Lerner, “The Capital City and Mount Rushmore: The Place of Public Monuments in American Political Culture of the Progressive Era and the 1920s” (PhD diss., John Hopkins University, 2001), ProQuest (UMI 3006294); Matthew Shaer, “The Sordid History of Mount Rushmore,” Smithsonian, October 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/sordid-history-mount-rushmore-180960446/.

- “American History, Alive in Stone,” Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota, last modified May 16, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/moru/index.htm; “A Different View of Mount Rushmore,” Indian Country Today, April 15, 2012, https://newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/a-different-view-of-mount-rushmore-rgresUhTKkSwAq9JtX17CQ/.

- Information on Jefferson Davis’s four highway markers can be found online: “ID: J-21,” North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, accessed September 12, 2019, http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=J-21; “ID: K-16,” North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, accessed September 12, 2019, http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx-?MarkerId=K-16; “ID: L-4,” North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, accessed September 12, 2019, http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-4; and “ID: L-31,” North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, accessed September 12, 2019, http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=L-31.

- Anna Griffin, “Indians Want Jackson’s Name Off U.S. Highway,” Baltimore Sun, June 17, 2001, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-2001-06-17-0106170208-story.html; Christopher Arris Oakley, Keeping the Circle: American Indian Identity in Eastern North Carolina, 1885–2004 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 123–124.

- Chick Jacobs and Venita Jenkins, “The Night the Klan Met Its Match,” Fayetteville Observer, Charlotte Action Center for Justice (blog), January 18, 2008, http://charlotteaction.blogspot.com/2008/01/night-klan-met-its-match.html.

- Jacobs and Jenkins, “Klan Met Its Match”; Lorraine Ahearn, “Narrative Paths of Native American Resistance: Tracing Agency and Commemoration in Journalism Texts in Eastern North Carolina, 1872–1988” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2016), 127, 184.

- Tina Norris, Paula L. Vines, and Elizabeth M. Hoeffel, The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010, U.S. Census Bureau, January 2012, 5, fig. 2, https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/c2010br-10.pdf.