A few years ago, my mother suggested we go see an exhibition of cloth paintings at the Rosalind Sallenger Richardson Center for the Arts at Wofford College, the small liberal arts college in Spartanburg, South Carolina, where my late father had worked from the early 1980s to 2007. The exhibition was entitled Scraps from My Mother’s Floor and featured the work of Atlanta-based artist Dawn Williams Boyd (b. 1952). The collection stunned me both for the powerful commentary that each piece made on Black Americans’ lives, past and present, and the myriad ways in which Boyd made each cloth painting come to life through an intricate combination of fabrics, textures, shapes, material enhancements, sewing, and color schemes. These were works that commanded and demanded attention, much like the current issues and historical moments to which they speak—from police brutality to, in her newer works, air pollution, the Tulsa Massacre, and the Trump Era.

In summer 2021, I reached out to Boyd to inquire if she would be willing to speak to me about her life, the cloth paintings that appeared in the exhibition and appear on her website, and the motivations for and techniques behind her work. I was curious if and to what extent Boyd’s work might serve as a sanctuary for her—a safe, creative, generative space through which she could share her perspectives on the world, reflect on social issues through imagery, fabric, and design, and re-present African American history for herself and for others. It turned out that both the work itself and the space in which she creates it are sanctuaries indeed. On July 1, Dawn Williams Boyd generously welcomed me into her home for four hours, talking with me at length about her art, her childhood and education, and the beautiful house that her mother helped design—the childhood home in southwest Atlanta that she returned to several years ago and that has served as both studio space and sanctuary for her. In September 2022, Fort Gansevoort Gallery in New York City, which represents Boyd, will host a solo exhibition of her work. Our conversation here has been edited for clarity and space.1

DAWN WILLIAMS BOYD: This is my home. I’ve lived here since I was about ten. My family bought this house in the mid-60s. When we bought the house, it ended right here [gestures to the wall of the house at the point where the great room extension begins]. It was just a straight little ranch house. My mother was the kind of woman that looked at home and garden magazines back in the day when they had blueprints in the magazine, and she learned to make drawings of blueprints. She designed the house from this point onward.

When we moved here, the street that you came down, Bakers Ferry, was nothing but woods. It’s beautiful out here, best kept secret in Atlanta … it wasn’t developed much at all. It was farmland and piney woods, and she carved all of this out of what was just a tract piece of land. What we have in this neighborhood now are retired teachers, retired postal workers, retired Lockheed aircraft workers. The majority of them have passed away. But there are a few who are still around, who are in their early nineties, and so that’s really nice.

My mother [a school principal who opened the Omenala Griot Afrocentric Museum in Atlanta, now run by Dawn’s brother Kevin Williams] was the eldest of four sisters. She and her sisters and their mother all sewed their own clothes well into their middle years. The majority of them have passed away. I didn’t know that people bought clothes out of stores for the longest time. It seemed like everything I owned was made at home. My brother and I went to parochial schools so we wore uniforms for the longest time. It seemed like everything else we owned had been made by someone. The story I always tell is that I was that little girl on Easter Sunday morning, sitting in the backseat of my parents’ car on the way to church finishing the hem in my dress because mother had not quite gotten to it.2

At Home

MARGARET MCGEHEE: So is this [section of your house] mainly for your work and then you live in the other parts?

DWB: This is the public part of the house. There are bedrooms [in the] back there, but the two rooms that we are in, that’s my studio. This used to be a sunken dining room. Mother thought this was extremely cool, but, unfortunately, she made it from a carport and the concrete floor is starting to sink. This is where I work.

The house needs to be rehabbed. What I’d like to do is to rehab the kitchen and the sunken dining room, take a wall out between those rooms to make a studio space for my husband [the artist Irvin Wheeler] and myself. What we would really like to do is to put a studio space in the back, a two-story space where he can have his woodshop and a display on the main floor, and I would have my studio on the second floor. That would be ideal. We have both tried having studios that were not part of the house, but it just doesn’t work.

MM: Do you consider this space your sanctuary?

DWB: Yes, and the yard, and the neighborhood. I used to walk in the neighborhood. In either direction, you’re going to find large pieces of land that are just woods. It’s just woods. There’s no sidewalks, there’s no buses. When I came back here from Denver, I walked every morning for an hour, hour and a half. I took a different path every day.

I particularly consider this subdivision mine. This is where I grew up. I won’t say this is where I became the person that I am. I would say that Denver is probably that place because I consider myself to be an artist, and I became a working artist (versus an “artiste”) in Denver. The foundation of my career happened in Denver, but this is where I grew to be a person. This is my space right here. This subdivision, particularly this house, is where I feel most comfortable. Sanctuary is the place where you are safe, where you are at ease, where you are known and knowing. It is the place where you can sigh. You can let the world off your shoulders and be at home. And so this is my home. This is where I feel comfortable.

MM: Do you also find your work to be a sanctuary? Is your work a place where you can sigh?

DWB: Absolutely, because I get to work out all of the anger. All of my anger gets to come through my brain, through my fingers, into my artwork. I am happiest—and, at my age, I’m about making myself happy—when I am making artwork. All the time that my children were growing up—and this is a terrible thing to say—but having to go to PTA meetings, having to go to baseball practice, cheerleading practice, having to go to work, for that matter, having to buy groceries, to make food—all of that stuff took away from the time that I could make artwork. So when I retired, I was like, Yessss, I can make as much as I’d like to. I can literally make artwork from the time I get up in the morning until the time I go to bed at night. It’s very physically demanding, and I’m getting older. I’m not able to push it. But ten years ago, I would make artwork all day, every day. I wore out sewing machines because they would get hot from being used; I would trade them out.

So, yes, it’s absolutely a sanctuary for me. It is where I am engaged. It’s where I’m safe. It’s where I am calm. That’s not always true because sometimes I get overwrought because it’s not happening the way I want it to happen. But 99 percent of the time I am a happy camper.

I have had some times when I couldn’t make artwork. My husband was really ill for a year. When we first moved, I couldn’t make artwork, except on the side, on the scale of my sketchbook, but when I was able to snatch an hour to work on something in my sketchbook, that made me happy. All of the stresses that I was going through outside of that sketchbook, it was my reward for doing all the things that I knew that I had to do. I had to do these things in order to survive, to keep food on the table and a roof over our heads, and gas in the car. Now I’m happy and calm and inspired, and I’m safe because I know what I’m doing. And I’m happy when I am making artwork.

Early Years

MM: [Your parents] encouraged you in your art career and going to college for art?

DWB: My mother was a very dominant woman. She was used to getting her way, and she figured if she was paying, she should have things the way that she wanted it. She determined very early in my life that I would go to college, but I would not go to college in Georgia. She said, “You have the entire world. Choose any place you want, but it can’t be in Georgia.” Which is odd, because, at least at the time, if you were a Spelman alum, it was automatic that if you had a girl child she would go to Spelman. She had gone to Spelman, but she did not want me to go. She was always about broadening our horizons.

I have a single sibling—my brother, Kevin, who is two and a half years younger than I am. We went to private schools forever—Saint Paul of the Cross Elementary School, which is right over here on Harwell Road. Then I went to D’Youville Academy, which was in the Chamblee Dunwoody area of the city. My brother went to Marist Military Academy. And then I went to Stephens [College, in Columbia, Missouri]. [Kevin] traveled the world with Up with People for two years.

Mother was about preparing us for the world that we would live in versus the world that we were living in at that time, for what we would need to know and how we would need to interact in the larger world, which kind of separated us from the other kids in the neighborhood. It was kind of strange, but we survived it.

I was D’Youville’s only Black student in the history of the school. Kevin was not; he was the second generation of Black students at Marist. I was at D’Youville from ’66 [until the] school closed in ’69. I did not graduate, which bummed me out because I was really excited about graduating from that school, but they recalled the nuns to New York. The school was on an old plantation. Of course, I was living here [off of Bakers Ferry] at the time. When I first started going there, I-285 didn’t exist. We would go all the way through what was Gordon Road, Mosley Drive, and Hunter Street to Peachtree, go north from there through town, and then cut over at Ashford Dunwoody every day for a year. Meanwhile, they built 285. [In the car] were a bunch of boys who were Marist students and [myself]; Marist was our brother school. Just as the oldest boy in the group turned sixteen, they finished 285, so we could get around without having to go all the way through town.

MM: What was that like, in the late 1960s, to be the only Black girl in a sea of white girls?

DWB: It was educational. They had maids, which was fascinating to me. I got to visit their houses on occasion. The thing that was interesting was that of course the girls were very nonchalant about having maids. They had always had maids and nannies and they had always been Black, so it was not weird to them. But the maids reacted to me oddly, like “Where did you come from? And how is it that you are going to the same school that these girls are going to?” But that’s all I knew.

It was strange at first because the only white people I had known until that time were nuns and priests. But you adapt. They had the same kind of issues I had. They had boy problems. They liked to sneak cigarettes. They played hooky, those that had cars. I was very much into cheerleading. I was the first, again, Black cheerleader that Marist ever had.

MM: When you would come home and were interacting with friends in the neighborhood, did you feel that you were shuttling between two lives in a way, or two worlds? Did you find more commonality than similarity? Or was it just what you did?

DWB: It was just what I did. I didn’t really think about it too much. I think about it a lot more now, looking back on it, than at that time. I was one of those really busy teenagers, and I was terribly spoiled.

MM: Then you went to Stephens College?

DWB: Yes. Stephens was an all-women’s college at the time; it’s not anymore. They had a problem holding on to their students. [The students] would start there and then discover boys and that would be the end. They determined that they would have a program where they would [house one hundred first-year students] in the same dorm, they would do all their core classes together, and they would bond. It worked fairly well. I was the only Black student in that program. I had some fun times, learned a lot of bad habits while I was there. I spent a lot of time in the art department.

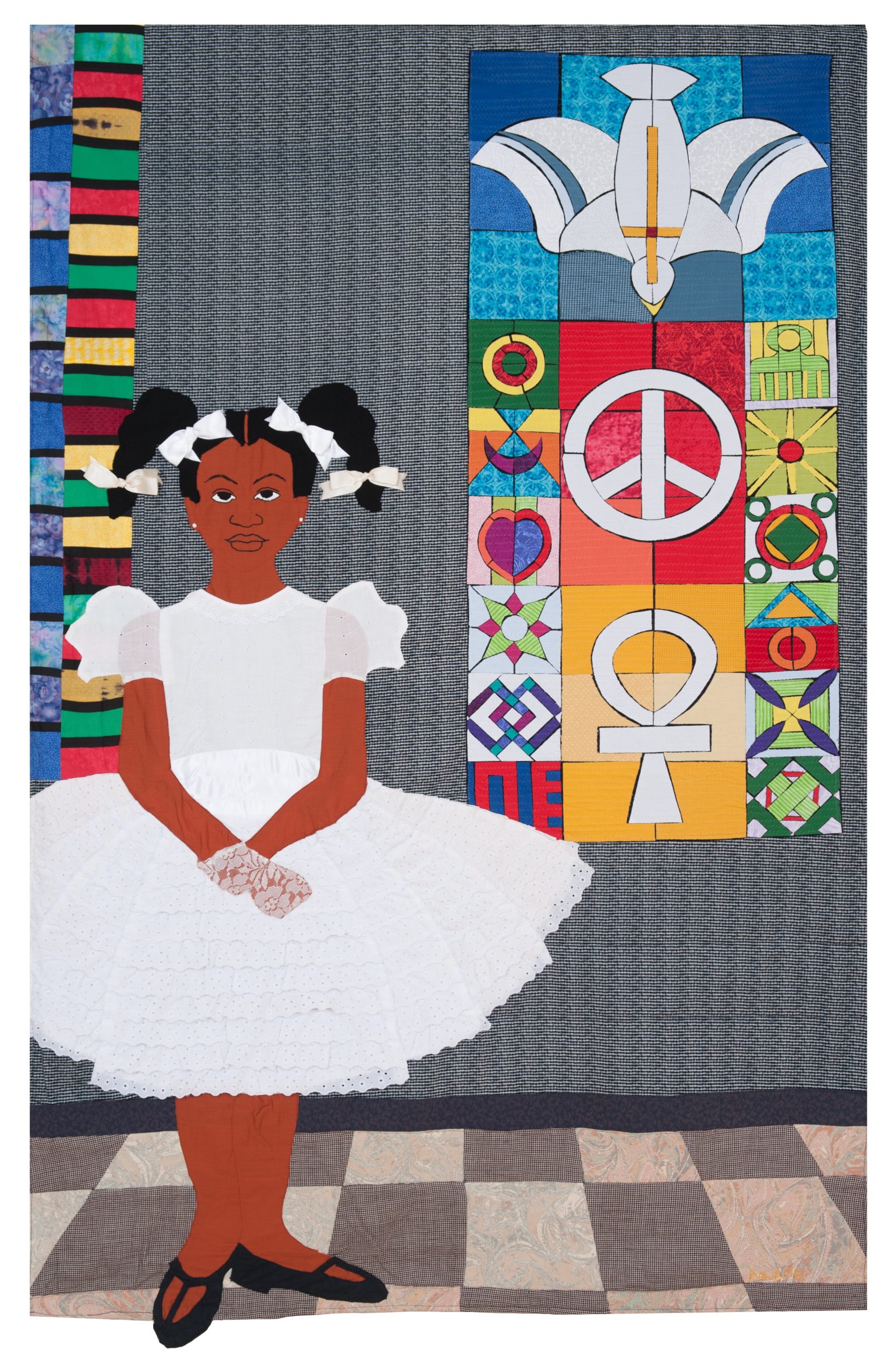

When I graduated from Stephens, I moved back to Atlanta. I worked for the Atlanta Regional Commission for a while. I met a man, and I moved to Colorado. The people that he knew there were young Black people who had steeped themselves in African American history. They liked to play cards on the weekends. They talked about our history, and I listened. I’m a big believer in libraries. The internet hadn’t been invented so I would go to the library or call my mother and say, “I heard blah, blah, blah.” And she would say, “Well, the book that you need is so and so.” I would go to the library and get that book or order it and read just enough so that I could tell the story visually. It was hanging out with people playing cards that got me interested in portraying the history of this country from an Afrocentric point of view.

The Work

MM: When did you move towards cloth and away from the acrylics?

DWB: I was asked by Metropolitan State College of Denver to do a teachers’ workshop on the artist Faith Ringgold. I became familiar with her work, and the one thing that was odd to me about her work was that instead of leaving her canvas stretched over stretcher bars she and her mother would take squares of fabric and then sew them to the bottoms and the edges. She would roll that work up, stick it in a tube, and mail it to wherever she was showing.

At that time, I was painting in acrylics on corrugated cardboard and on plywood. They were very large pieces. I was just beginning to show my work outside of Colorado and shipping them was a problem. The idea that you could take the artwork and fold it or roll it and put it into something small and ship it was brain busting. I thought, well, if you can do that, why not make the whole image out of fabric? I had enough sewing experience; I had made one quilt before that. The thought that you could make an entire image out of fabric and then fold it, put it in a box, take it to the post office, mail it. It was a revelation.

MM: Do you do some machine quilting in your pieces, or do you do it all by hand?

DWB: I do all the quilting by hand. I don’t own a long arm. Mine is really more structural than decorative. The concept of “quilt” is simply that you have multiple layers that you have attached so that they don’t come apart. So my work is tacked.

MM: Did your work in portraiture and figure drawing come into play with your cloth paintings?

DWB: I’ve always been into the human form, particularly that of women. Women are more interesting to draw because of the curves that women’s bodies have. I’ve always been into the human form. It identifies what I do.

There are two sources of my work that involve women. One is my Catholic school upbringing. I am a big fan of the Virgin Mary. The Catholic church lost me in sixth grade because they couldn’t explain to me how you can be a virgin and give birth because I knew where babies came from. I like to tell her story, not her story as it’s written, but her story as maybe it should have been written. In Denver, the second group I was in was Sankofa [Art Collective] in the early 2000s. Two of the participants were lesbians and because we had art in common, we hung out. I found them fascinating, their whole community. I was the odd woman out because I’m not gay, but I would sit and watch them for hours. That’s what originated the Ladies’ Nightseries specifically. The very first one, Billie’s Bar and Grill (2009), is a portrait of these particular women.

In Baptizing Our Children in a River of Blood (2017), you see several women and little kids dressed in white. The ladies are just like the mothers in the church that you see standing in the back, who come and tell you to stop talking in church, or they don’t even tell you, they just stand there and look at you. But it was the children that I concentrated on in that piece because, with all of the police violence that we have had in the last few years, it worries me that children of all ethnic backgrounds, of all races, see what’s on television. And they see the video games and they see the news and so I worry what kind of adults they are going to be. Every day on television, you see a policeman shooting someone just because of the color of their skin, or just because of who they love.

And then we have COVID. All this time they can’t interact with their Black or Hispanic or Asian friends. And that’s the only way that people learn to live with each other. They need to do that as little kids from nursery school; they need that interaction. They need to be able to touch, and say, “Your hair is different from mine. And why is your skin that color? Why are your eyes blue and mine are brown?” They were not able to do that. Then they watch these adults who were supposed to know better, on television, marching and invading the White House, and kneeling on the necks and killing people, and it’s all over the internet.

That piece is about the kids. When you get baptized, you go through a ritual and when you get dumped in the water or have the water poured over your head, depending upon which system you’re in, that’s supposed to designate a change in the way that you are perceived. When they are approaching the policemen, their little outfits are white, but when they come through the policemen, the outfits are pink from the blood that they’ve been dipped in. And they’re fractured from the experience. Then you have the adults on the shore, not only the mothers in white, who are sort of having to guide their children through this process, you have the adults on the shore who are witnesses, but helpless witnesses, because there is little that they can do besides witness and then receive their children on the other end in their fractured, baptized state and say to them, this is something that you went through. But what we have to tell the children is that your life does not have to be defined by this experience that you have had. That’s going to be really hard for us to do.

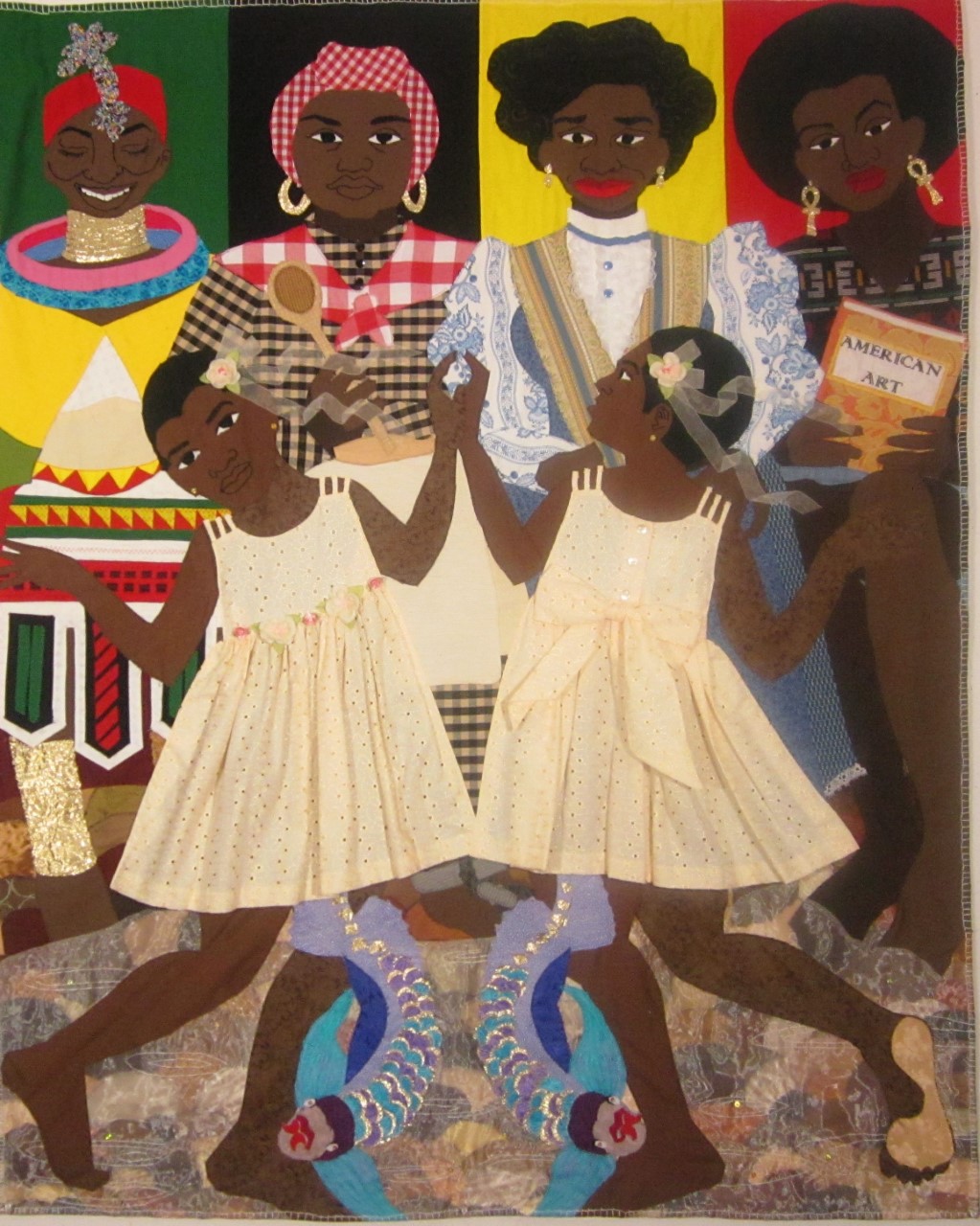

MM: The piece Piscean Dancer (2016), which features four African American women throughout history, can you talk a little bit about that piece, and is that you, is that your ancestry, or is it more representative of African American women in America?

DWB: It’s a personal piece because I’m Piscean. My husband and I frequent Goodwill stores. I don’t even remember why I started doing it, but I started collecting little girl dresses. Now, my daughters are grown and until a year ago, all my grandchildren were male. I had no reason whatsoever for little girls’ dresses, but I looked in my closet one day and I had about four or five of them. I had been thinking about this piece. I said, OK, I’ve got little girls in the loop and the dress, and I know what that is. I know that they’re going to be dancing. I had thought about the title because Pisces is a dual sign. I had done the research on the dragonfish, which are in the bottom. And so I said, OK, you need a background. I started thinking about the African American and Black women throughout history, all of the things that we have had to learn, the situations we have had to adapt to and the things that we have brought with us from our ancestors through today, and the things that have been important for us. I think the most important thing has been education and the betterment of our race through education, through the acquisition of property, through the passing down of knowledge and if not land, then little tiny bits of wealth, that brought up [generations] of women.

I had a book about the Ndebele women in Africa. The story of Mammy is a part of American history. I don’t know very much about the women after slavery in the Victorian era, if you want to call it that, with the high collar and the pompadour. That whole imagery has always been really interesting to me. Then of course you have the ’70s, Black Power, Black Is Beautiful woman, and the Afro and the art. All of them were artists of one sort. The Ndebele paint their houses; the mammies of that era did everything—they sewed, they cooked, they nursed, they made quilts out of the leavings from the cotton gins. Once that background was done, it just fit perfectly. Their feet are all in a small pond of water and there are rocks in the bottom of the pond, symbolizing the struggle that they have gone through for generations. The little girl is dancing, and she symbolizes the moments of joy and the moments of freedom that these women might not have had that I enjoy on their behalf. There are several Piscean elements included. I really loved the dragonfish because I was born in 1952, which, according to the Chinese calendar, was the year of the water dragon. I was born in Neptune, New Jersey, and I have this thing for blue glass and fish.

[Regarding the cloth painting Those Bones: Atlanta, GA 1979 (2004)], I listened to the radio more than the televisions. I moved to Colorado in [the mid-1970s], and I heard about the disappearances on the radio. It was weird to hear the names of the streets that you are familiar with on national news. It was several years later, actually, that I did the piece. I had already been doing several pieces about lynchings in acrylics. It was just another of the many instances where I heard something, did some research on it, had an idea about how to illustrate the story, how to bring people into conversation about the story, and it had a lot of construction elements that I had recently learned to do. I had learned to embroider when I started doing that piece. I wanted to do things that involved other materials. I had been using mostly cotton up until that time, so I began to incorporate some other fabrics.

[My work involves] always at least two stories for me: What story am I telling? And then what am I doing on the surface that I have not done before that I’m exploring? This one [points to a work in progress] is going to be unusual. It is called This Uninhabitable Earth and is about air pollution; it is going to be mostly shades of gray. They’re all wearing gas masks at a point in time we might come to when the air is unbreathable. It will be a gray sky with a gray cityscape in the back. It’ll be all gray, all gray. And as you come forward, you get more and more color, but it’ll all be muted grays. I’m planning to do this in cotton for the foreground, but there are going to be layers of organza in between the barrier, the background, the middle ground, the middle foreground, and the real foreground to obscure the hard lines.

This [notebook] is my research. I find images of what I need. I could draw all of this stuff, but who has that kind of time? That is what the internet is for. I use different pieces of each image that I find for

different parts of the sketch. Each cloth painting has a folder with its images, and then you wind up with this [full design of a piece]. This is my Tulsa piece. It will be five feet high and ten feet long. You can see all the notes that I’ve made about what time of day it happened because that will inform what the sky looks like, where the shadows are, where the light is, what the circumstances were. I read, for example, that they had mass graves. I will show people being pulled out of churches. People being pulled out of their houses in their nightclothes. This is a plane that’s dropping handmade bombs because they burned all of Black Wall Street. From here on, this is all houses that are on fire, the smoke and flames. I need to find a particular piece of fabric for the tree. I know the piece of fabric that I want, but I don’t know if it still exists where I saw it last. Buying fabric is my favorite part. I try to be very conservative with the amount of money that I spend on fabric because I have lots of fabric, but there’s some things, like varying shades of brown, that I have to have over and over again.

Once I get all of these traced, I’ll roll the tracing papers up inside the big piece and add it to the pile that’s done with phase five and then finish those. By the end of July, I get to go buy fabric. I’ll go through the fabric store like a hurricane. Then I’ve got to bring it all home, throw it in the washing machine, put it in the box that applies. I need to buy a new thread. I already have my sheets because I have been collecting them for years. I have all the background sheets that I need. Then comes the hard part of tracing all these pieces onto individual cuts of fabric and rough-cutting them. All the parts for this piece will go in one plastic bag. I’ll put that aside until I’ve done all thirteen pieces. Once I’ve done that, then I will come back and open them up and do all the drawings onto the sheets of all thirteen pieces. Then, once I have gotten to that phase, I pull one bag out, one sheet out, and then we begin to assemble. I do the entire surface for one piece and then put that away, do [another] entire surface, and go through thirteen like that. Eventually, I’ll get to the place where I’m embroidering. It’s kind of disappointing to me when I finish a piece and then have to start from the beginning for a new one. But if the new one that I’m going to do has already had the first six stages finished, then I go from collage to collage versus from collage to finished piece. I don’t like starting all over again. I like to have them all just go along as a group, assembly line–style, and we all get to the same place at the same time. Eventually, I’m signing all of them. That’s the way I like to do it.

MM: Does the topic of the piece usually come to you first and then you sketch it? How do you get from, say, “I want to do something about the Atlanta Child Murders” to what we see as the end product?

DWB: I have ideas, and I keep a notebook with me where I will write the idea down. A lot of times it will come very visually as a finished piece. Doesn’t always finish the way it started, but I usually see it. I make myself notes that say, “This is what I heard. Research this.” And while I’m waiting to research it, I’ll say, “OK, I want it to be this big. I want these elements in it.” I might do a really tiny little sketch. “I want to have a coffin with X number of people. I want to have a woman screaming. I want to have this girl tied to a tree.” So you’ve got to do the tree, think about how you want to portray a pine tree. You have to have her tied, so you have to figure out how to do the rope. Do you want to embroider it? Do you want to do something that’ll stand out from the surface? All the little things that I want to do will go into that note. Then that note might sit for a year or more. That little notebook has had the pages torn out and stuck in the sketchbook. And eventually I do a sketch that is [around 8.5″ × 11″]. Then you go from a note sketch to a full-size sketch that is 5′ × 5′, whatever it is. And, until recently, I have been blowing them up by hand, which meant graphing them out, which took forever.

I have a solo show coming up at Fort Gansevoort Gallery in September of ’22, and I have thirteen pieces to do by then. I realized that I’m never going to make this deadline if I continue to do that. So I spent about a month and a half researching projectors that blow the piece up. So I’ve gone from weeks of graphing out one piece to forty-five minutes with the projector.

The Trump Era series that I started, the plan was to do twelve shows with my group and to feature one work within this series per show. I had planned on twelve pieces, but then COVID came along and Fort Gansevoort came along. I couldn’t do the shows and the gallery sold all the work that I had made. Now I’m having to make all new work. Fortunately I had more than twelve ideas for this Trump Era series.

We’re debating whether we’re going to keep the name because no one likes to say that word—Trump. The fact of the matter is that it was never about him for me to begin with. It was about the issues that he exacerbated. The issues existed before him, they have continued to exist, and will exist long after. It’s the problems that we, as a society, have: we have the environment, we have people being forced to move from one place to another, we have women’s rights, we are rehashing things like voting rights. The thing about Trump was that he took us back in time and to make up that time is going to take a lot longer. Even though he is not president of the country anymore, his philosophy, and that of his adherents, who have crawled out of their closets where they were hiding their antisocial ideas, has permeated the world. We are still in and are going to be suffering from that philosophy for some time.

We were well on our way, I thought, to a more enlightened society. We were not there yet. We were a long way from being perfect. But we were well on our way towards dealing with the environment, dealing with the immigration process problems. Women’s rights—that was done. Voting rights—it was done. And now we’re having to go back and do that stuff all over again because of him. And so I thought it was very appropriate that he should bear the name of all this bitching and complaining that I was doing. Again, the gallery thinks that a lot of people don’t want it. I understand that, but you need to understand that this is not over. I’m still talking about it, and I want to talk about some things like Tulsa that recently had its one-hundred-year anniversary. I hadn’t been planning to talk about voting rights, but now I have to. The thirteen pieces that I am working on are still talking about those things.

Dawn Williams Boyd creates large-scale “cloth paintings,” with fabrics garnered from myriad sources, to tell the stories of her times, her country, and her people. Her artwork reflects her interest in American history as it affects and is affected by its African American citizens, particularly as seen through the eyes of women and children. Boyd’s most recent work considers how U.S. politicos are influencing the human condition well beyond our country’s physical borders. She is represented by Fort Gansevoort Gallery, New York, and lives and works in Atlanta, Georgia.

Margaret T. McGehee is associate professor of English & American studies and associate dean for faculty development at Oxford College of Emory University. Dr. McGehee’s current book project—”Atlanta Fictions: Women Writers’ Urban Imaginaries”—focuses on the Atlanta imaginary in modern and contemporary fiction. Her scholarly work has appeared in Southern Quarterly, Cinema Journal, Studies in American Culture, Southern Spaces, North Carolina Literary Review, and in Tison Pugh’s Queering the South on Screen (UGA Press) and Gina Caison, Stephanie Rountree, and Lisa Hinrichsen’s Remediating Region (LSU Press).

1. Dawn Williams Boyd, accessed February 24, 2022, https://www.dawnwilliamsboyd.com/.

2. “Get to Know Us,” Omenala Griot Afrocentric Museum, accessed February 24, 2022, http://www.omenalagriot.com/events.