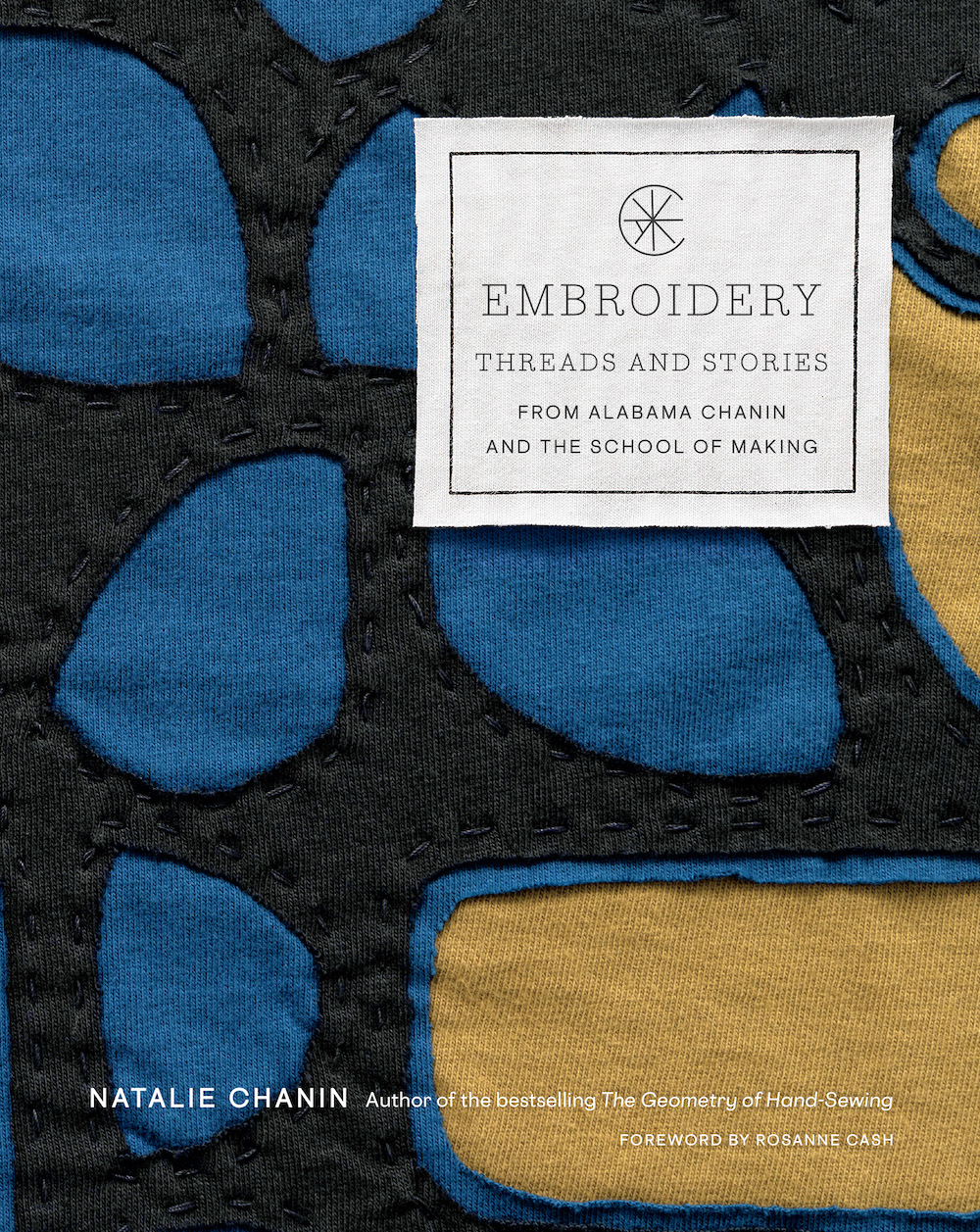

Natalie Chanin is the founder and head designer of Alabama Chanin, the 21-year-old company focused on sustainable design based in Florence, Alabama. Chanin’s latest book, Embroidery: Threads and Stories from Alabama Chanin and The School of Making (Abrams, October 2022) mixes lessons in sewing, design, and embroidery with her personal story and the evolution of Alabama Chanin. We are pleased to share an excerpt from Embroidery on Chanin’s return to her home in Alabama.

The origin of the word Alabama is still debated. Some believe it is derived from the Choctaw language, translated as “thicket clearer”—hinting at the agriculturally adept tribes that cleared the thicket for cultivation. As a child, I was certain that this was the best interpretation, as, left untouched, the mesophytic forest of our region produces a landscape so dense and thick with vegetation that it can be difficult to navigate. With an annual rainfall just four inches shy of rainforest designation, the woods and creeks are deep, dark, breathing organisms, filled with plant and animal life, that constitute one of the most biodiverse regions in North America.

Once I’d made the decision to return home [in 2000, after years spent in Europe and New York] to search for the quilters of my childhood, this dense vegetation, red clay earth, and the verdant smell of home began to dominate my dreams. Nights dreaming of wooded paths, long gravel roads, and meandering creeks were followed by days and weeks of writing a proposal for the creation and production of a collection of two hundred one-of-a-kind, stitched-by-hand T-shirts. This collection would be accompanied by a twenty-two-minute documentary film, entitled Stitch, about old-time quilting circles. After raising money and organizing production of the T-shirts and short film, I called my aunt and explained my big idea, asking if she knew of a house I could rent as a production studio, project headquarters, and living arrangements for a month. A few days later, she called back. She had the perfect place. The future production studio, built by my paternal grandfather in 1958 with, and for, his best friend, sits next-door to my aunt’s home—the house of my maternal grandparents—where I had spent much of my youth. I remember holding the phone, astounded at the notion that this project would come to life in my own grandparents’ backyard—the place my journey began. In a moment, I saw this work unfurling like an impossible dream, coming to life in unbelievably surprising ways.

That December, I rented a car and drove with a friend, and future business partner, from New York City to Alabama. It was an adventure that crossed eight states and included stops at thrift stores for project materials, dreaming, taking photographs, and visiting with friends and family along theway. Three days and a thousand miles later, we arrived, late in the evening of December 23. As we pulled into the drive, the redbrick house was barely visible, as the future project headquarters had been uninhabited for the previous five years and Mother Nature had begun the process of repossessing the property for her own. My aunt and mother had used a chain saw to cut a path through the dense overgrowth to the back door. Passing through the teeming mass, we made it inside. I was home.

We unloaded the car, which smelled lived-in and was filled to the roof with bags of used T-shirts, and entered the house. It was not an olfactory improvement: the closed-up smell of mildew, ghosts of long-ago meals, an odor of unseen animal life, and abandonment. Once settled, I tucked myself, exhausted, into bed, a simple mattress placed on the 1970s vinyl floor of the open main room. Lying there in the dark, perfectly still, I was filled with utter doubt and dread. My mind racing, I dissected my life and its decisions: running away from this place, working, living, loving; experiencing accomplishments and failures, adventures, successes, and losses. I started to cry and couldn’t stop. I felt my entire life culminating in this dark night of the soul, waiting for ghosts and unknown creatures and bitter cold to seep through the cracks and crevices of floorboards, walls, and windows black with night. Throughout those hours of darkness, my senses remained highly tuned for sounds and smells, for the snakes that were most certainly coming to join me in the warmed bed as soon as I closed my eyes. Finally, in the very early morning light, I fell asleep only to awake with a start from dreams of snakes and living, moving topiaries. Despite my fear, I was greeted by a beautiful, clear day; there were no snakes or ghosts to be found.

December light in Alabama is crisp and bright, the sky a remarkable color of winter blue. On this Christmas Eve morning, the first in the brick house at Lovelace Crossroads on County Road 200, I got up and went to the kitchen, cleaned a small place on the counter, and made my morning tea. Sitting down on one of the stools that my aunt had sweetly left for us, I looked around the room and took stock. In addition to the vinyl flooring, I noticed the walls of the room were covered with an old, broad-board paneling. I stood, wondering what the years-long coating of life and abandonment hid underneath. I cleaned one board, discovering a beautiful pine board. This paneling—historically prevalent across the region—was designed to mimic paneling originally cut from the magnificent southern longleaf pine, the Alabama State Tree, whose ancient forests across the state were called “Giants of the South.”

Reclaimed, I found the one board spectacularly beautiful. Inspired, I cleaned one more, and then another. Board by board, I worked my way around the entire room throughout the day. As the sun began to set outside the kitchen window, I sat back down on the stool, drinking in the room, the light, and the pine boards. In reclaiming them, I realized that I had also reclaimed something of myself, my history, my home, my family, and my life.

I then remembered the Rollo May quote and understood anew that commitment and creativity and life are healthiest when they are not “without doubt but in spite of doubt.” Watching the sun slip down behind the thicket, I remember thinking, yet with the presence of doubt, “I can do this.”

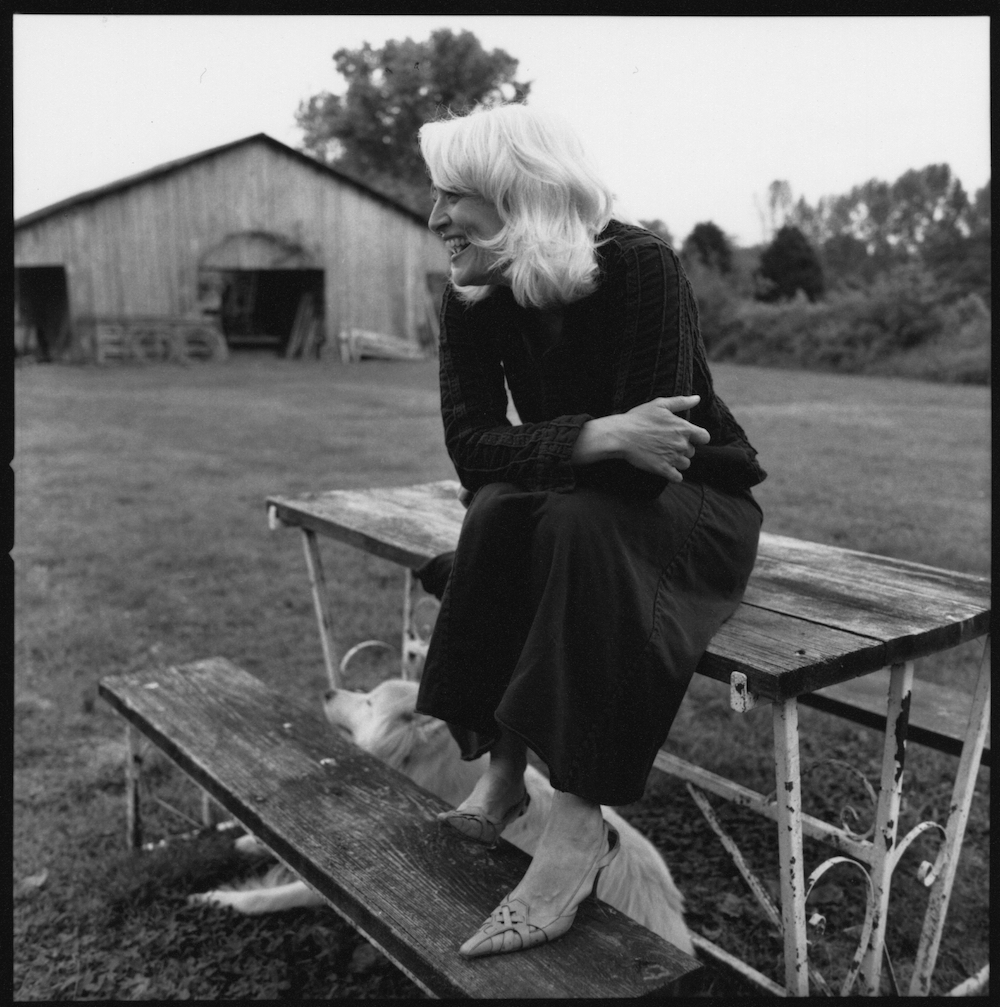

Natalie “Alabama” Chanin is the owner and designer of Alabama Chanin. She has a degree in environmental design with a focus on industrial and craft-based textiles from North Carolina State University. Chanin has worked as a fashion design, stylist, and costume designer; in 2000, she returned to her home to begin the sustainable work that has become Alabama Chanin. Since 2000, Alabama Chanin has expanded to include a family of businesses: the Alabama Chanin collection, The School of Making, and Building 14 Design + Manufacturing Services.

“Alabama” is excerpted from Chanin’s new book, Embroidery: Threads and Stories from Alabama Chanin and The School of Making (Abrams, October 2022).