As I write in the summer of 2021, the US is in its fourth wave of the coronavirus pandemic. Amid the celebration of widely available and highly effective vaccines, federal, state, and local governments have abandoned most public health protocols and failed to consider how their decisions have repeatedly led to the nation’s coronavirus case load spiraling out of control for most of the pandemic. Perhaps nowhere has the crisis of COVID-19 been more grave than in prisons, jails, and detention centers where imprisoned people have been left with little recourse or protection. In the early phase of the pandemic, organizers and advocates pushed for the release of incarcerated people, rightfully pointing out that carceral facilities would be a primary vector of the virus, but their release has been uneven and woefully inadequate, even as prison outbreaks catch headlines. Unfortunately, carceral politics that deem criminalized people disposable have permeated the responses of not only governors and mayors but also criminal justice reform advocates in determining which prisoners are worthy of release. Liberal prison reformers have too often hewed to narrow legal categories of “nonviolent” or “pretrial” in their demands for early release, leaving the vast majority of incarcerated people in the lurch.1

While limiting demands around early release is often framed as pragmatism—that state officials will be more sympathetic to demands that are viewed as reasonable rather than radical—this move has given both liberal and conservative “law and order” politicians broader cover to deny more and more people their freedom. By shoring up divisions over which incarcerated people are worthy of protection from premature death and which are not, racism is normalized and extended in the name of alleviating it for a narrow slice of the penal population. In contrast, abolitionists have challenged these narratives and practices through the antiracist demand to “free them all” during the COVID-19 pandemic—calling attention to the fact that the source of danger is not with criminalized people but with mass criminalization and racist state violence.2

We can find an oft-overlooked precursor to contemporary demands to free them all in the abolitionist organizing surrounding a different crisis: the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The New Orleans Critical Resistance (CR) campaign for amnesty for prisoners of Hurricane Katrina elucidates how periods of acute crisis serve as political opportunities for pushing bold demands that can interrupt punitive narratives and disseminate abolitionist analysis while organizing people for the long-haul work of undoing the endemic crises and violence of the carceral state.

In the spring of 2006, I was making plans to spend the summer in New Orleans to support grassroots organizing for an anti-racist and anti-capitalist just reconstruction of the city in direct contrast to the neoliberal and white supremacist recovery being pushed by elites. Like others, I was horrified by the Bush administration’s abdication of the city and broader Gulf Coast and saw the region as pivotal to movements for racial, economic, gender, and environmental justice. Although I had made initial ventures into antiprison activism and had some personal and political relationships in New Orleans prior to the storm, I knew little about post-Katrina abolitionist organizing. But then a political mentor reached out to me to see if I would be interested in putting some of my time in New Orleans into supporting a “Prisoners of Katrina” amnesty campaign crafted by Critical Resistance (CR). As explained to me, thousands of people jailed at New Orleans’s notorious Orleans Parish Prison (OPP) had been abandoned for days to the floodwaters in tandem with the state’s racial criminalization of Katrina survivors for acts law enforcement defined as “looting.” Critical Resistance, a national prison abolitionist organization with a local New Orleans chapter, was organizing to gain amnesty for all of these people. The abolitionist call for amnesty, while visionary, was not utopian. As former New Orleans CR organizer Tamika Middleton explained, “When you got into it, it was the only logical step. … What would be the thing you would ask for that’s less than this when you consider all the things that [jailed and criminalized people] experienced?” The demand for amnesty was designed to meet the scale of harm produced by the state’s punitive disaster response. Invigorated by this liberatory horizon, I signed up to do what I could for the amnesty campaign.3

While the New Orleans Critical Resistance amnesty campaign did not succeed in gaining amnesty for all people incarcerated during and in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, returning to its vision illuminates how expansive abolitionist demands can create new ground for organizing. Situating this abolitionist demand in the lineage of southern reconstruction organizing, Critical Resistance’s call for amnesty refused the false division of the deserving from the undeserving. CR emphasized that justice could only begin when the state acknowledged the racist violence it had inflicted on storm survivors through incarceration and the criminalization of survival tactics; and when it made material reparations that would improve incarcerated and criminalized people’s lives in the here and now. During the amnesty campaign, abolitionist organizers intervened in popular narratives that blamed criminalized people for the punitive violence enacted against them in the wake of the storm. Through grassroots research, media-making, and public events, CR documented and publicized the carceral strategies of disaster racism that city and state officials had attempted to keep out of view. CR demonstrated that the city’s turn to law and order as disaster management was a magnification of the everyday operations of the OPP—a key node of state racism before, during, and after the storm. The amnesty campaign served as a project for the New Orleans CR chapter to rebuild around and bring more people into abolitionist activism following Hurricane Katrina. CR activists furthered their media and legal skills, deepened organizing relationships across the city, and advanced their collective abolitionist sensibilities, which would prove vital for future struggles to undo the New Orleans carceral state.

Crisis of Criminalization

The drowning of New Orleans was not natural. It was produced through decades of disinvestment in critical flood protections alongside massive state investments in the carceral infrastructures of policing, jails, and prisons. The racist scripts of criminalization and disposability structured the state’s response to struggling Hurricane Katrina survivors. In the days leading up to the hurricane’s landfall, Mayor Ray Nagin ordered a mandatory evacuation of the city, failing to provide resources for residents without cars or anywhere to evacuate to, meanwhile declaring that the city jail, Orleans Parish Prison, was exempt from evacuation orders. Instead of gathering necessary supplies, OPP Sheriff Marlin Gusman spent the crucial days and hours before the storm overcrowding the jail with hundreds of prisoners who were evacuated from neighboring parishes. At the same time, the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) arrested three hundred people between August 26 and 29, 2005, on mostly municipal offenses such as unpaid parking tickets or public drunkenness. By the time the levees broke, upward of eight thousand people—pre-trial prisoners unable to make bail, state prisoners serving short sentences, juvenile prisoners, and immigrant detainees—were held captive in the 6,500-bed jail. The state had responded to the crisis with arrests, not releases, and more imprisonment, not less.4

As toxic floodwaters inundated 80 percent of New Orleans, OPP prisoners were left to fend for themselves. One OPP survivor recalled:

Time continue[d] to pass by, water still rising. No food for us to eat. Finally, a female deputy came by [and] we shouted to her about our conditions. She then replied there’s nothing we can do because there’s water everywhere and she left. At this point water had risen to at least four feet deep. I thought for sure I would never see freedom again.

While deputy sheriffs abandoned their posts, the people incarcerated at OPP sought to save each other by any means necessary: breaking cell doors to free people from the flood, swimming to higher floors, helping youth float on mattresses, waving signs and setting fires to signal for help, and breaking walls and windows to escape the nightmare altogether. When the state finally began evacuating the prison, things did not get better. Department of Corrections officers commanded the evacuation in riot gear with tasers and rubber bullet guns and instructed prisoners to leave everything—including their medications and legal paperwork—behind. Prisoners were funneled through the sprawling OPP complex until they made it to the Central Lock Up building, where they waited for rescue boats. Some people struggled to keep their heads above the polluted water while waiting upward of twelve hours.5

These survivors did not find relief as they were bussed out of the city. The state sent them to prisons where they were often left in makeshift muddy prison camps—prisons within prisons. There, they continued to go without medical care or proper food and guards routinely pepper sprayed, beat, and sexually violated them. They were shuffled around Louisiana’s extensive archipelago of prisons and jails, and the state demonstrated no concern for their rights to habeas corpus or pending release dates. Thousands of individuals served extended sentences so common that prisoners called them “Katrina Time.” Some people were locked up well beyond their release dates, while others served multiple times longer than the maximum sentence allowed for crimes they had not even been formally charged with. Rather than the state guaranteeing OPPsurvivors’ right to counsel and a fair and speedy trial, the Louisiana legislature passed a bill during a Katrina special session that barred “lawsuits by people kept in prison past their release dates.” Nearly a year after the storm, as late as May 2006, criminal justice advocates were pressuring a judge to release OPP survivors who had yet to see counsel.6

State officials’ and media’s dominant racist narrative of OPP prisoners as criminals and therefore deserving of state violence magnified the state’s punitive approach to Black Katrina survivors. Mainstream media immediately recast Black New Orleanians searching for provisions in abandoned stores as violent “looters” taking advantage of a crisis for personal gain. While the nopd covered up cop killings of Black survivors and ignored white vigilante violence, law enforcement spread falsities about riots in the streets and shootouts against police, which mainstream media widely circulated as indisputable fact. The racist idea that New Orleans had turned into a space of uncivilized urban warfare underpinned Governor Kathleen Blanco’s infamous announcement that she was sending three hundred Arkansas National Guardsmen “fresh back from Iraq” to New Orleans, and that “they have M-16s, and they’re locked and loaded. … I have one message for these hoodlums: These troops know how to shoot and kill, and they are more than willing to do so if necessary, and I expect they will.” Blanco’s deployment of militarized law enforcement was matched by Mayor Nagin’s directive that the nopd stop their search-and-rescue mission on August 31 and refocus on arresting “lawless” survivors. The state’s first “rebuilding project” was a temporary jail at the New Orleans bus and train station referred to as “Camp Greyhound.” Instead of leveraging the state’s resources to set up emergency medical care or developing a robust housing plan for displaced New Orleanians, state officials prioritized locking up hundreds of Katrina survivors for criminalized disaster survival strategies.7

Amnesty toward Reconstruction

As the organized abandonment of Black New Orleans was broadcast across the globe, then New York City–based CR organizer Kai Lumumba Barrow remembers assessing that “this was the worst disaster Black folks have experienced since slavery. … It [was] like a historical loop that was coming back again for Black people in this city specifically.” Although the historical connections between this moment of Black suffering and previous ones were readily apparent to racial justice organizers, at the time, racist moral panics around looting overdetermined survivor narratives, as the media lauded Sheriff Gusman and propagated myths of rioting OPP prisoners. For CR activists, it was critical to push back against the normalization of racial criminalization and to seek material redress for those subject to punitive disaster racism.8

But what was to be done? Relationships built over the preceding years between local and national CR activists proved vital for the development of an abolitionist response to Hurricane Katrina. When Middleton was waylaid by the storm, Barrow coordinated a conference call for New Orleans CR activists alongside national CR staff and members to strategize an abolitionist response to the storm.

CR cofounder Ruth Wilson Gilmore offered one that stuck: the granting of amnesty for all Prisoners of Katrina. This included the full release and complete expungement of the criminal records of all people who had been deserted in OPP and those who were arrested for trying to survive in the face of the state’s malignant negligence. The demand for amnesty did not play into the liberal trope of delineating who was deserving of redress based on categorizations of “innocence” and “guilt” or “nonviolent” and “violent.” Rather, the call for amnesty insisted that no one should have been subjected to carceral violence before, during, or after Hurricane Katrina and that everyone was deserving of unmitigated freedom. Moreover, as Tamika Middleton recalls, “The amnesty campaign allowed us to keep OPP in the conversation” at a time when the state’s relentless disciplining and displacement of Black New Orleans made it difficult to keep up with all the different forms of violence to which state officials were subjecting Katrina survivors.9

The abolitionist demand for amnesty aligned with the articulation of post-Katrina struggles within an expansive framework of Black Reconstruction and human rights in the Black radical tradition. Critical Resistance had long linked its antiprison activism to Black Reconstruction’s “abolition democracy,” where abolition meant not only the abolition of slavery but the creation of a new type of society where slavery would be unthinkable. The New Orleans chapter of

redress against the US government’s anti-Black racism in their 1951 petition We Charge Genocide. This political position refuted that the goal was simply the incorporation of Black people into the liberal state but rather contended that true democracy would not be possible while the US continued its genocidal program against Black humanity. As Barrow explained, lifting up amnesty as “a human rights issue as opposed to a local issue or domestic issue” allowed CR “to raise questions around the PIC as a whole and the ways it impacts Black bodies specifically.” The radical human rights framework said that the problem was not that the New Orleans criminal legal system operated in cruel and unusual ways in the wake of the storm, but that routinized racist cruelties underpinned jailing as a long-standing state project. These crises were not evidence of the state’s failure during the storm but revealed the normalized operations of the carceral state taken to its logical conclusion. Critical Resistance’s demand for amnesty highlighted that the state’s culpability for the abandonment of OPP lay in its fundamental power to criminalize and cage.11

Organizing against Carceral Crises

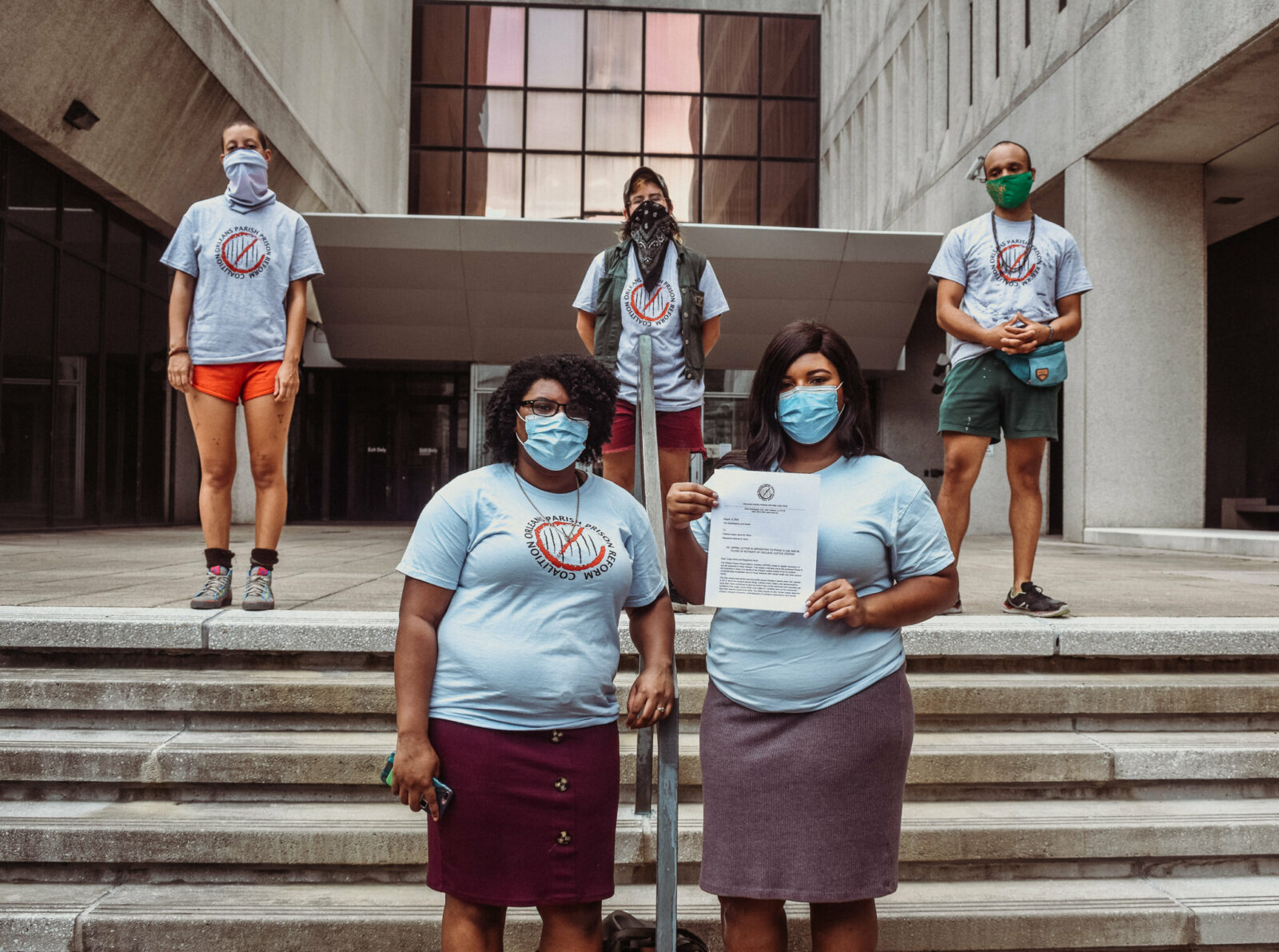

The first step in the amnesty campaign was to publicize the brutality of the state’s broadbased turn to racial criminalization as disaster policy. The prevailing narrative, circulating in the weeks after the storm, was that Sheriff Gusman had prepared for the hurricane to the best of his abilities and that he and the Department of Corrections thoroughly managed the jail’s evacuation. Critical Resistance joined with organizations including the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, Friends and Families of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, the Southern Center for Human Rights, the naacp Legal Defense Fund, the aclu, and Human Rights Watch to hold a press conference to expose what had really gone down at the jail. Significantly, press conference organizers did not depict the abandonment of OPP as an anomaly but as part of the everyday crises of racist violence that had marked the New Orleans punishment regime for decades.12

Outside the still empty OPP, flood lines in view, press conference speakers detailed how prisoners were left to the contaminated floodwaters without food, water, or medical care and how guards liberally deployed pepper spray against prisoners. Middleton asserted that Gusman was unequivocally responsible for failing to make an “evacuation plan … despite knowing that the levee break would put everyone in the jail in danger.” Joe Cook of the aclu emphasized there were still hundreds of OPP prisoners missing from the official evacuation lists, and although Gusman claimed no one had died, a sheriff’s deputy reported that while searching for survivors she found three dead people. Family members of OPP survivors shared the anxiety and fear of being unable to locate their loved ones for two to three weeks after the storm and their frustration that the state was not releasing people whose bail had already been paid.13

Middleton stated, “Katrina’s aftermath reflects the way we as a nation increasingly deal with social ills. Police imprison primarily poor Black communities for crimes that are reflections of poverty and desperation.” As Xochitl Bervera of Friends and Families of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children noted, the “disaster before the disaster” that entrapped so many people inside OPP during the floods was the tripling of the jail’s size over the preceding years. As the largest per capita jail in the US at the time of the hurricane, OPP had been consistently mired in scandal, lawsuits, and protests due to inhumane conditions and high rates of premature death. And now the city was doubling down on the same racist, punitive tactics—prioritizing Camp Greyhound over meeting New Orleanians’ material needs, routinely arresting people for quality of life offenses such as public urination and littering, increasing interagency policing through military police in Humvees and helicopters, and criminalizing people’s movement through a citywide curfew—all while city leaders insinuated that New Orleans would be safer if it were rebuilt whiter and wealthier.14

What was needed was a total reconstruction of the New Orleans criminal legal system. Activists called for a redefinition of public safety away from the “top down” solutions of prisons and policing and toward “bottom up” solutions of investments in food, shelter, and living wage work. Yet they could not move forward with such a transformation until carceral state violence against storm survivors had been addressed. Hence, Middleton announced the need for the Critical Resistance amnesty campaign. “We demand an independent investigation of the evacuation of Orleans Parish Prison. We also demand amnesty for those who were arrested for finding food and trying to help themselves in the aftermath of Katrina, and those whose cases are in legal limbo” and are doing Katrina Time. Through the press conference, abolitionists made clear that accountability could only come through amnesty as a step toward reversing and reducing the state’s power to punish.15

Building on the press conference, CR worked to get the amnesty campaign off the ground. However, the hurricane had significantly fractured the organization’s New Orleans chapter. Thousands of New Orleanians were displaced well into 2006 and those who were able to return home in that first year were stretched by the everyday work of rebuilding their lives. As any organizer knows, a clear organizational structure with well-defined points of entry for people to get involved is fundamental to moving their frustrations and desires into collective action. With Middleton stretched by her duties as CR’s southern regional coordinator, Barrow decided to split time in New Orleans to get the amnesty campaign running and rebuild the New Orleans chapter. Through the base-building activities of political education and leadership development, Barrow brought people into activism, built relationships, and deepened people’s abolitionist politics. Moreover, the amnesty campaign offered veteran and new CR members a concrete project with the support of CR member Mayaba Liebenthal, who was brought on as an amnesty staffer. By setting the campaign up with multiple entry points, CR allowed for people with diverse interests and skillsets to advance that campaign while furthering people’s own organizing skills and sensibilities.

A central prong of the amnesty campaign was conducting research into what had happened to people doing Katrina Time. Activists with Critical Resistance and other criminal justice reform organizations spent months tracking down OPP survivors and interviewing people as they were released from the jail to collect their stories of what happened before, during, and after the hurricane; and piecing together the documentation that had not been lost to the floods. These case studies illuminated how the state’s refusal to evacuate OPP and then the state’s failure to keep track of people’s locations and charges led people to be imprisoned months beyond their initial sentences—leading one woman to die behind bars after her release date. Furthermore, their research detailed that disaster law and order translated to the prevalence of the nopd arresting people for “looting” items such as cold drinks and sausages and for curfew violations outside their own homes. The case studies served as a bedrock of the campaign in that they illustrated the callousness of Katrina Time and offered concrete evidence that unsettled the hegemonic discourse that the state’s law and order response mitigated the disaster of lawlessness.16

CR injected its grassroots research into public discourses to shift popular narratives—no small task as local and national media parroted the talking points of law enforcement and tough-on-crime elected officials. Along with holding press conferences and sharing the case stories they collected with local media, CR leveraged the national scale of the organization to publicize the amnesty struggle. A key tool to this end was Ashley Hunt’s documentary I Won’t Drown on that Levee and You Ain’t Gonna Break My Back. The film told the story of OPP’s abandonment and was circulated across the nation to activist groups seeking solidarity with New Orleans. Through this combination of research and media work, an abolitionist narrative began to emerge around OPP and Katrina Time.

Moreover, CR decided to organize faith leaders to call on the city and the state to grant amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina. The CR believed that elected officials would not be able to ignore a call for amnesty from religious leaders speaking of healing and forgiveness. The activists spent the summer and fall of 2006 developing relationships with an interfaith group of religious leaders and congregants, leading to a number of Christian, Muslim, Jewish, and Unitarian Universalist houses of worship signing onto the call for amnesty.17

This interfaith support was the foundation for a weekend of events CR organized around International Human Rights Day in December of 2006. Named “Amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina: A Weekend of Reconciliation and Respect for Human Rights,” CR underscored that the only way New Orleans could heal was through the state’s taking responsibility for the carceral violence it had imposed by granting amnesty. The goals of this weekend were threefold: to bring more people into the amnesty campaign in particular, and into long-term abolitionist organizing in general; to garner media attention for what had happened to Prisoners of Katrina to change the public conversation; and to push state officials to act on amnesty. Toward these goals, CR held workshops on human rights, roundtable discussions on redefining public safety, a keynote by renowned abolitionist scholar and Critical Resistance cofounder Angela Y. Davis, and a closing pray-in for amnesty.18

Bringing Davis to speak heightened the profile of the campaign, facilitated the recruitment of local activists to CR, and deepened the conversation on abolition. In addition to highlighting the campaign’s talking points, Davis emphasized how the “ghosts of slavery” structured the human rights disaster at OPP when the state did not think that “prisoners deserved to be treated as human beings.” This treatment followed the lineage of slavery whereby enslaved people “were not recognized by the law” except through a “negative standing, the standing of guilt, the ability to be found guilty.” Calling for amnesty for all Prisoners of Katrina was an effort to dismantle the racist logic that allowed the prison industrial complex to be an answer to disasters.19

The culminating event was Amnesty Sunday, when faith leaders dedicated their services to the campaign. After services, the public was invited to Watson Memorial Teaching Ministries on St. Charles Avenue to pray for reconciliation and healing through amnesty. The pray-in was accompanied by hundreds of bright blue fans marked with white doves because, as Ebony Hawkins of the Sixth Baptist Church explained, “Doves are known for having a fierce desire to return home to their nest and their family, much like folks who remain imprisoned or displaced because of the storm.”20

While the weekend of events had strong turnout and media coverage and drew more people into the local CR chapter, it did not move state and city officials as organizers hoped it would. While some out-of-town activists declared that the weekend of events accomplished the goals of the campaign, New Orleans CR activists were clear that the campaign was not over. They forged ahead by working with other grassroots organizations to bring post-Katrina human rights abuses to light in the international arena. In the first few years after the floods, it was commonplace for un representatives to catalog the post-storm state of affairs. CR shared their case studies and demands with the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and also testified in Geneva with the goal that international pressure would compel state officials to act. Unfortunately, the US proved impervious to international critique.21

Furthermore, a subset of CR members worked with law school students to research the legal mechanisms for granting amnesty in Louisiana. The best option they identified was blanket executive clemency from the governor. For CR, the use of clemency would signal that the state had failed to enact justice and that the public could be better served “outside the bounds of the traditional criminal justice system.” However, the mass displacement of Black New Orleanians redrew the Louisiana electoral map, paving the way for the gubernatorial election of neoconservative Bobby Jindal in 2007. This political realignment foreclosed the possibility of the governor’s mansion as an organizing target. A second, much narrower legal avenue was expunging people’s records. Under Louisiana law, one’s misdemeanor arrest records could be destroyed while felony arrest records could be expunged—meaning that they could be removed from public access but not completely erased. However, if someone had served jail time, as was the case for the vast majority of people who were unable to afford bail, their records were ineligible for expungement. Despite the narrowness of record expungement, clearing some charges from people’s files had the potential to bring people home post-storm as “the frequent use of background checks, particularly for housing and employment, greatly jeopardizes displaced residents’ rights to return home.” Shifting their definition of victory in response to shifting conditions on the ground, CR organizer Mayaba Liebenthal retells that CR decided that it would “define [the amnesty campaign] as a win” if even “ten people’s records were wiped clean.”22

Critical Resistance joined together with the organization Safe Streets/Strong Communities to hold an expungement day for not only those who had done Katrina Time, but anyone seeking to clear their records. Over four hundred people showed up, demonstrating the long-lasting harm a felony arrest could have on people’s access to housing, education, and work. While the state’s stringent requirements for expungement meant that only around fifty people were eligible for full expungement, CR decided to hold ongoing expungement clinics to lessen the enduring ramifications of criminalization on people’s everyday lives.23

Building toward Freedom

While Critical Resistance did not succeed in gaining amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina, this does not mean the project did not advance the ongoing movement for prison abolition. Through the struggle of the amnesty campaign, CR developed abolitionist organizing infrastructures that both interrupted the dominance of disaster racism and offered a foundation for later anti-jail activism. Through the painstaking work of documenting and amplifying the crisis of racial criminalization that characterized the state’s disaster management, CR helped to popularize an antiracist critique within local and national activist circles of the law and order response to Hurricane Katrina. It also helped to place its critique within the long-standing politics that deemed Black people and places as disposable. And by refusing to exceptionalize what had happened at OPP, CR helped to set the stage for future grassroots activism against jailing. CR‘s ideological struggles did not stop at critique but, importantly, offered the expansive demand of amnesty in the Black radical human rights tradition. By refusing to leave anyone behind, CR demonstrated the hollowness of rendering some people and not others as deserving of freedom. Having a concrete demand to anchor their activism proved vital in rebuilding the New Orleans chapter with many entry points for people to gain political education and plug into the everyday work of activism.

CR sowed fertile ground for future struggles to shrink the size of OPP. When Sheriff Gusman pushed to expand the jail with FEMA rebuilding funds a few years after the storm, CR and other grassroots organizations galvanized the Orleans Parish Prison Reform Coalition (OPPRC) to organize against Gusman’s plan and turn this political threat into an opportunity to scale back the jail’s capacity even more. Underlying the campaign to downsize OPP was the collective understanding that concern with conditions of confinement without attention to the size of the jail was not enough. The goal was to make it so that fewer people would be subject to any form of punitive violence at all. Through building on the critiques and relationships forged in the immediate post-Katrina years, OPPRC succeeded in pushing the city council to reject Gusman’s plan in 2010 and, by placing a new bed cap on the jail, ensured that OPP was 80 percent smaller in 2015 than it was during Hurricane Katrina—significantly reducing the number of New Orleanians sent to jail.24

During the COVID-19 pandemic, organizers have been met with limited success in “freeing them all.” But it does not mean such campaigns and demands have not been worthwhile. It may be another year, or five, or ten, before we recognize the reverberations of this work, but I am sure they are out there—already shifting terrains of discourse and debate, already recruiting more people into freedom work, already creating horizons whose consequences we can’t even imagine yet. Periods of acute crisis are not times to confine our visions of what liberation might entail, but to confront the conditions that produce harm and violence straight-on. Abolition calls on us to dream, think, and organize for what we truly desire—there is no other way of making our world freer.

This essay first appeared in the The Abolitionist South Issue (vol. 27, no. 3: Fall 2021).

Lydia Pelot-Hobbs is assistant professor of geography and African American & Africana studies at the University of Kentucky, where she writes and teaches on carceral geography, racial capitalism, and social movements. She is currently writing a book on the consolidation and contestation of the Louisiana carceral state.

Header: Press conference outside Orleans Parish Prison, including Xochitl Bervera (speaker) and members of Friends and Families of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, Critical Resistance, the NAACP, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International. Photographs by Ashley Hunt are from his documentary works on Hurricane Katrina, including Notes on the Emptying of a City (2011) and I Won’t Drown on that Levee and You Ain’t Gonna Break My Back (2006).NOTES

1. The concentration of preventable deaths from coronavirus in carceral facilities has been highly documented from the reporting of criminal justice think tanks such as Prison Policy Initiative as well as the New York Times. See Prison Policy Initiative, “COVID-19 and the Criminal Justice System,” accessed November 24, 2020, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/virus/index.html; and Jordan Allen, Sarah Almukhtar, Aliza Aufrichtig, Anne Barnard, Matthew Bloch, Sarah Cahalan, and Weiyi Cai et al., “Coronavirus in the US: Latest Map and Case Count: Cases in Jails and Prisons,” last modified May 31, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html.

2. Free Them All for Public Health, accessed May 31, 2021, https://freethemall4publichealth.org/.

3. Tamika Middleton, in discussion with the author, March 29, 2021.

4. Diane E. Austin, “Coastal Exploitation, Land Loss, and Hurricanes: A Recipe for Disaster,” American Anthropologist 108, no. 4 (December 2006): 671–691; Clyde Woods, “Les Misérables of New Orleans: Trap Economics and the Asset Stripping Blues, Part 1,” American Quarterly 61, no. 3 (September 2009): 769–796; Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, “Lockdown Louisiana,” in Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas, ed. Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013); ACLU et al., Abandoned and Abused: Orleans Parish Prisoners in the Wake of Hurricane Katrina (Washington, DC: ACLU, 2006), 10, 20–30.

5. Jodie Smith and James Rowland, Temporal Analysis of Floodwater Volumes in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina (Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior, 2007), 59, https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1306/pdf/c1306_ch3_h.pdf; ACLU et al., Abandoned and Abused, 35, 43–53, 57–62.

6. ACLU et al., Abandoned and Abused, 70; “Louisiana: Detainee Abuse Requires Federal Probe,” Human Rights News, October 4, 2005, https://www.hrw.org/news/2005/10/04/louisiana-detainee-abuse-requires-federal-probe#; Brandon L. Garrett and Tania Tetlow, “Criminal Justice Collapse: The Constitution after Hurricane Katrina,” Duke Law Journal 56, no. 1 (2006): 148; Barry Gerharz and Seung Hong, “Down by Law: Orleans Parish Prison before and after Hurricane Katrina,” Dollars & Sense, March/April 2006, 44; Leslie Eaton, “Judge Steps in for Poor Inmates without Justice,” New York Times, May 23, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/23/us/judge-steps-in-for-poor-inmates-without-justice.html.

7. “Military Due to Move in to New Orleans,” CNN, September 2, 2005, http://www.cnn.com/2005/WEATHER/09/02/katrina.impact/; US, 109th Congress, 2nd Session, A Failure of Initiative: Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2006), 248, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CRPT-109hrpt377/pdf/CRPT-109hrpt377.pdf; Gwen Filosa, “New Detention Center Opened,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), September 3, 2005. While some Katrina survivors reappropriated food and medical supplies, others did take things like televisions to barter with for a ride out of town. See Jordan Flaherty, Floodlines: Community and Resistance from Katrina to the Jena Six (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2010); and Dan Berger, “Constructing Crime, Framing Disaster: Routines of Criminalization and Crisis in Hurricane Katrina,” Punishment & Society 11, no. 4 (October 2009): 491–510. On the NOPD’s killing of Black storm survivors, see A. C. Thompson, “Body of Evidence,” ProPublica, December 19, 2008, https://www.propublica.org/article/body-of-evidence; and United States of America v. Michael Lohman, Criminal Action 10-032 (E.D.La, 2010), Bill of Information for Conspiring to Obstruct Justice, February 3, 2010, https://int.nyt.com/data/int-shared/nytdocs/docs/107/107.pdf. On white vigilante violence, see Welcome to New Orleans, directed by Rasmus Holm (Copenhagen: Fridthjof Film, 2006), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V__lSdR1KZg; and A. C. Thompson, “Post-Katrina, White Vigilantes Shot African-Americans with Impunity,” ProPublica, December 19, 2008, https://www.propublica.org/article/post-katrina-white-vigilantes-shot-african-americans-with-impunity. Hundreds of newspapers reported that New Orleans Katrina survivors were “out of control” and “thugs.” A few examples are: “Military Due to Move”; “Police Kill 5 as Contractors Attacked,” Associated Press, September 4, 2005; and “‘Hurricane Katrina: Crisis, Recovery’ for September 4,” MSNBC Special Reports, September 5, 2005, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/9218509/ns/msnbc-morning_joe/t/hurricane-katrina-crisis-recovery-september/#.W7WEUpNKjqQ. While a few publications eventually made retractions about New Orleanians responding to the storm with violence, these stories were published with little fanfare—ensuring the initial reports remained dominant. Jim Dwyer and Christopher Drew, “Fear Exceeded Crime’s Reality in New Orleans,” New York Times, September 29, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/29/us/nationalspecial/fear-exceeded-crimes-reality-in-new-orleans.html#:~:text=NEW%20ORLEANS%2C%20Sept.&text=Looting%20began%20at%20the%20moment,edge%20of%20the%20French%20Quarter.

8. Kai Lumumba Barrow, in discussion with the author, January 18, 2016; “Looters Taking Advantage of Katrina Devastation,” CTV News, August 31, 2005, http://www.informationliberation.com/?id=674.

9. Barrow, discussion; Middleton, discussion; Mayaba Liebenthal, in discussion with the author, April 27, 2016; Ruth Wilson Gilmore, email message to author, November 17, 2020. On organized abandonment, see David Harvey, The Limits to Capital (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982); Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning” in Engaging Contradictions, ed. Charles R. Hale (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

10. W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880 (New York: Free Press, 1998); Angela Y. Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003); Middleton, discussion. On the CR articulation of abolition as a remaking of society, see Critical Resistance Publications Collective, “The History of Critical Resistance,” Social Justice 27, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 6–10; and Critical Resistance Publications Collective, ed., Abolition Now! Ten Years of Strategy and Struggle against the Prison Industrial Complex (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2008). For more on the Third Reconstruction framework, see Saladin Muhammad, “Hurricane Katrina: The Black Nation’s 9/11! A Strategic Perspective for Self-Determination,” Socialism and Democracy 20, no. 2 (July 2006): 3–17; and Eric Mann, Katrina’s Legacy: White Racism and Black Reconstruction in New Orleans and the Gulf Coast (Los Angeles: Frontlines Press, 2006).

11. Civil Rights Congress, We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of the United States Government against the Negro People (New York: Civil Rights Congress, 1951); Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 58–59; Barrow, discussion.

12. “Breaking News from the Times-Picayune and Nola.com – Hurricane Katrina – the Aftermath Weblog for Day 8, Sunday, September 3, 2005,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), September 3, 2005; “Looters Taking Advantage of Katrina Devastation,” CTV News, August 31, 2005, http://www.informationliberation.com/?id=674.

13. I Won’t Drown on that Levee and You Ain’t Gonna’ Break My Back, directed by Ashley Hunt (Corrections Documentary Project, 2006), https://vimeo.com/17174758.

14. I Won’t Drown; Calvin Johnson, Mathilde Laisne, and Jon Wool, Criminal Justice: Changing Course on Incarceration (New Orleans: Data Research Center, 2015), 1; Louis Hamilton et al. v. Victor Schiro et al. Civ. A. No. 89-2443; Louisiana Coalition on Jails and Prisons, “LCJP Sues Orleans Sheriff,” Inside, April/May 1982, p. 8, Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons Records, box 2, folder: Louisiana Coalition, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; “Death in Custody,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), April 9, 1999; Lolis Eric Elie, “Who Protects?,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), April 9, 1999.

15. Elie, “Who Protects?”

16. Marina Sideris and the Amnesty Working Group, “Amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina: A Critical Resistance Special Report,” in Hurricane Katrina and Criminal Justice: Response to the Periodic Report of the United States to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, November 2007, p. 1. Critical Resistance’s grassroots research and interviews were joined by the work of Safe Streets/Strong Communities and the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, which also collected incarcerated people’s stories. Those stories became primary sources for the ACLU National Prison Project’s definitive and extensive report, Abandoned and Abused.

17. Barrow, discussion.

18. Critical Resistance, “Media Kit: Amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina Weekend,” December 2006, in the author’s possession.

19. Liebenthal, discussion; Andrea Slocum, in discussion with the author, May 9, 2016; Angela Y. Davis, “Amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina Keynote,” transcript, December 9, 2006, in the author’s possession.

20. Critical Resistance, “Faith Communities Call for Healing and Reconciliation during Amnesty Sunday Services across New Orleans,” press release, November 30, 2006, in the author’s possession.

21. Diana Chandler, “Angela Davis Will Be at Prisoner Rights Forum,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), December 7, 2006; Gwen Filosa, “Prison Activist Takes Katrina Tour,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), December 11, 2006; “Angela Davis Speaks Out on Prisons and Human Rights Abuses in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina,” Democracy Now!, December 28, 2006, https://www.democracynow.org/2006/12/28/angela_davis_speaks_out_on_prisons; Jesse Muhammad, “Amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina,” Final Call, last modified January 12, 2007, http://www.finalcall.com/artman/publish/National_News_2/Amnesty_for_Prisoners_of_Katrina_3185.shtml; Liebenthal, discussion; Sideris and Amnesty, “Amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina.”

22. Liebenthal, discussion; Sideris and Amnesty, “Amnesty for Prisoners of Katrina,” 18, 19.

23. Barrow, discussion; Liebenthal, discussion; Slocum, discussion.

24. Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, “The Contested Terrain of the Louisiana Carceral State: Dialectics of Southern Penal Expansion, 1971–2016” (PhD diss., CUNY Graduate Center, 2019); Matt Davis, “New Jail Building Approved by City Council; Sheriff Must Close Others When It’s Built,” Lens (New Orleans, LA), February 3, 2011, https://thelensnola.org/2011/02/03/jail-ordinance-passe/; Ordinance, City of New Orleans, Calendar No. 28,291, January 6, 2011, in the author’s possession.