being property once myself/ i have a feeling for it,/ that’s why i can talk/ about environment . . . —Lucille Clifton, 1972

These quacks [the political economists] would make wreck of the affections, in exchange for incessant production and accumulation . . . It is indeed the moral economy that they always keep out of sight. —James Bronterre O’Brien, 1837

“America is Mississippi,” Malcolm X asserted in 1964, as he appeared in Harlem alongside Fannie Lou Hamer. “There’s no such thing as the South—it’s America.” Over the summer and fall of 2022, as this issue of Southern Cultures took shape, Mississippi produced an extraordinary archive of moral manifestos that echoed this conflation of the state and the nation. Mississippi’s Congressman Bennie Thompson—who “draws inspiration from the legacies of Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, Aaron Henry and Henry Kirksey,” according to his official website—offered one vision of accountability in his role as chair of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol. Simultaneously, rival claimants to moral authority raised the racialized specter of individual vice—debt, sex, freeloading—to redistribute wealth upwards.1

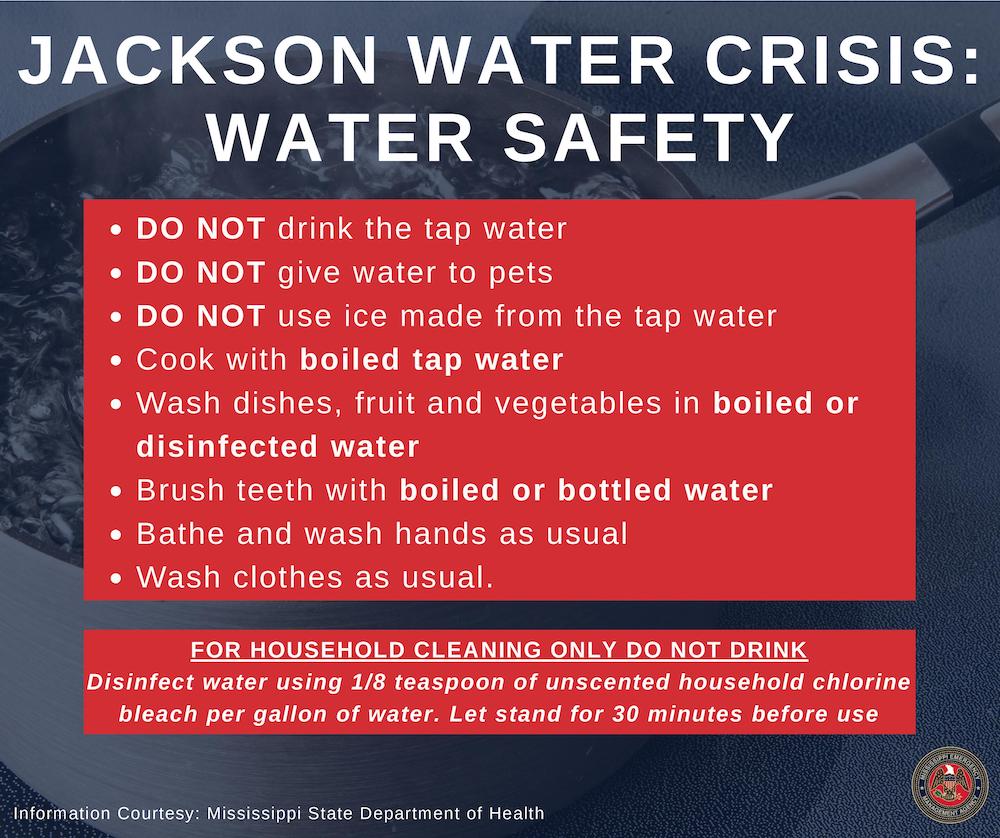

The first of these moral assertions came from an unlikely source. On August 30, the Mississippi State Emergency Management Agency tweeted out some helpful guidelines for the residents of Jackson. The capital city—over 80 percent African American—had endured four “boil water” advisories since June, and in the last week of August, record rainfall had swelled the Pearl River to flood stage. The O. B. Curtis Water Treatment Plant, already running on back-up pumps, failed entirely. The cloudy brown water that had been intermittently flowing out of taps abruptly ceased, and residents were left with not even enough foul-smelling, contaminated water to flush toilets for days on end. Even when water pressure returned the following week, no one could say when the water might be drinkable: for at least eight years, the federal Environmental Protection Agency has deemed the city’s water in violation of national standards, and two federal lawsuits are underway over its levels of lead. The entire crisis replayed in sweltering August a related emergency from February 2021, when a freeze shut down the capital city’s water system for more than month.

But in the midst of an infrastructure collapse decades in the making, the governor maintained the moral high ground: in June 2020, he vetoed a bipartisan bill that would have helped the Jackson municipal water system recover some of the revenue lost when a private contractor botched the billing process. To be sure, Governor Tate Reeves acknowledged, residents had been overcharged, but granting them relief would amount to “politicians say[ing] that individuals are not responsible for paying their water bill.” Moreover, the Republican governor cautioned, the legislation could not guarantee that relief would only go to “the impoverished or needy.” In a city in which one in four residents lives below federal poverty lines, the state would prioritize fraud prevention over water itself. And as Jacksonians boiled their brown water in 2022, so free was the Magnolia State from any pressing public needs that its legislature passed an income-tax cut for its wealthiest residents, eliminating $524 million from state revenues.2

As affected residents were quick to point out, the crisis simply threw into stark relief the asset-stripping and slow violence that had become business as usual. In its eagerness to shed the social responsibilities of government, the Reagan Administration shut down federal aid for water and sewer systems. White flight created rings of suburbs around Jackson that fought to avoid taxing themselves to pay for the city water services they shared. Public subsidy followed affluent whites to the suburbs: highways and airports drew tax dollars, but municipalities like Jackson were left to ratchet up water bills as their remaining source of operating revenue. The magic of the market would step in where the government now abdicated collective responsibility for the basics of shared life. For Mississippi’s capital, this alchemy took the form of a $90 million contract with the international engineering giant Siemens Inc., which promised operational savings but delivered instead a bug-ridden automated billing system. In a malign reversal, Jackson residents who never received their bills—let alone the estimated $2 billion in infrastructure investment the city requires to meet environmental standards—now found themselves painted by the state’s Republican leadership as delinquent debtors. Jacksonians could not expect the state to bail them out of their “overdue balances,” reasoned Governor Reeves, as he vetoed bond issues and repayment plans in 2020.3

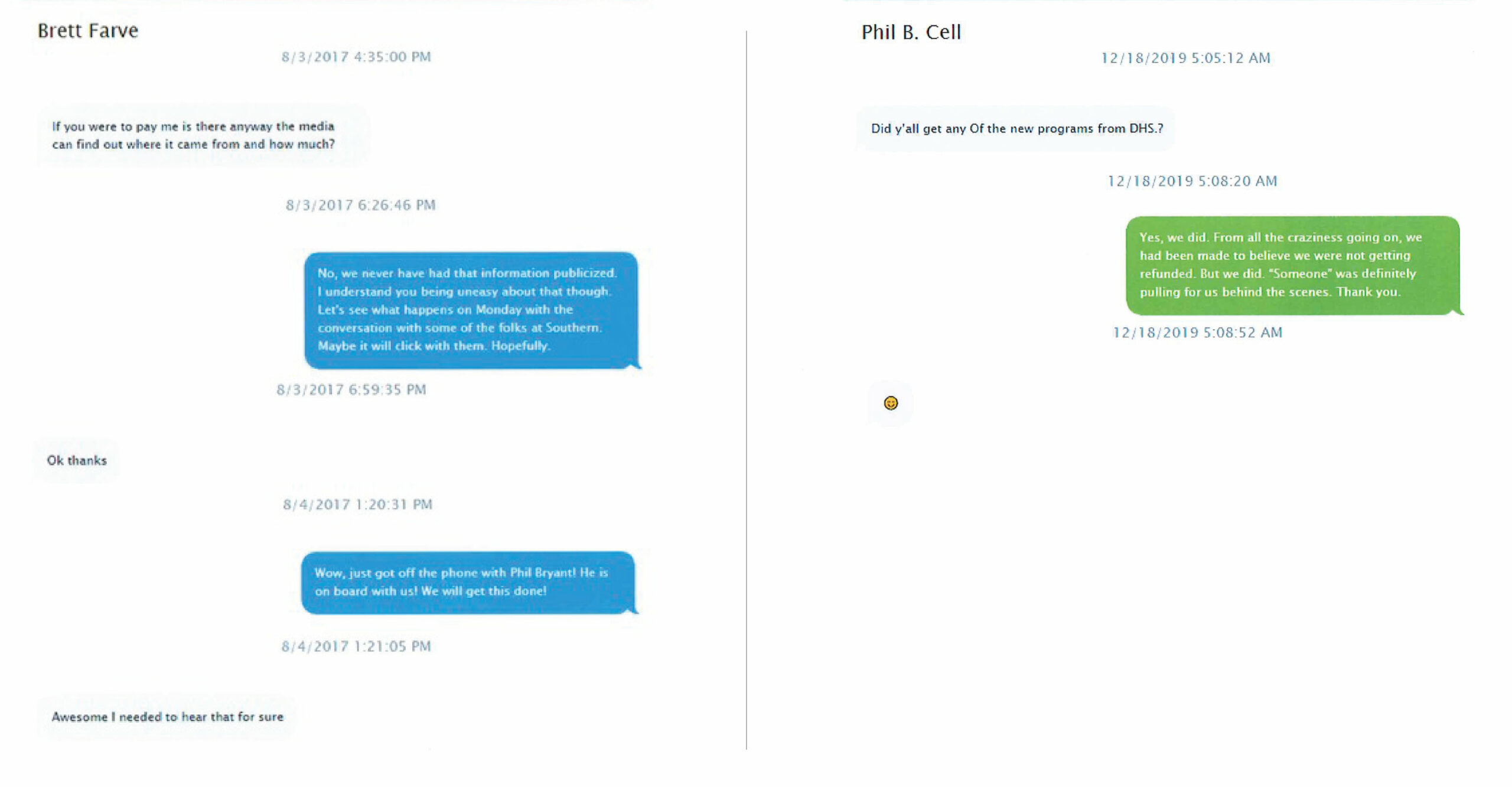

Similar vigilance against moral hazard animated another cache of headline-grabbing documents out of the nation’s poorest state a few weeks later. The nonprofit Mississippi Free Press made public the text messages exchanged by major players in the state’s years-long effort to prevent federal Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) from reaching the parasitical toddlers that the nation intended it for. TANF, larded with surveillance and “sanctions,” had replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children as a showpiece of the punitive turn in policy after 1980. During the presidency of Bill Clinton, the post–civil rights New Democrats scrambled to catch up to the GOP’s “get-tough” governance. Under the fiercely racist sign of Ronald Reagan’s folk demon, the “welfare queen,” both national parties recast social provisions as criminal subsidies. As historian Julia Ott shows in these pages, the old anti-labor alliance of white southern Dixiecrats and northern financial interests remade itself in the new economy, sluicing public resources to highest brackets of asset-owners through tax policy that favored capital gains over earned income.4

The Mississippi TANF scandal revealed in 2022 was merely a more nakedly egregious display of the same logics. Following the national condemnation of structural poverty as, at best, a personal failing and, at worst, a transparent fraud, the Mississippi Department of Human Services vigilantly policed the neediness of the 11,700 households who applied for direct assistance, and, in the poorest state in the country, determined that only 167 actually need the $170 in cash benefits—the lowest level of aid and the highest rejection rate in the nation. Meanwhile, the agency’s appointed head, John Davis, offered the millions in federal poverty alleviation funds to his white cronies, for pet projects like a volleyball stadium at the University of Southern Mississippi. His September 22 guilty pleas on federal conspiracy and theft charges followed an original 2020 revelation by state auditors, who called the $70 million swindle “‘the most egregious misspending my staff have seen in their careers.’” But the revolting scheme was most eloquently expressed in the emoji-sprinkled, poorly edited text messages among a depressingly predictable cast of the undeserving rich: evangelical philanthropists, celebrity football players, and unaccountable Republican state officials like Davis and his Trump-adjacent patron, then-Governor Phil Bryant. In the anti-democratic space designed by Mississippi’s Jim Crow electoral rules, Bryant made his political career on regressive taxation and accomplished at the state level the same upward redistribution that Ott documents as the South’s gift to white wealth nationally.5

“A budget is a moral document.” This slogan, variously attributed, appeared in a full-page ad in Politico in February of 2011, as Congress debated the proposed federal budget. The ad was sponsored by the progressive evangelical Sojourners network as part of their national campaign against Republican proposals to slash $61 billion in federal spending for programs like Head Start, Pell Grants, home heating assistance, community health centers, and maternal nutrition. “What Would Jesus Cut?,” demanded tens of thousands of coordinated emails directed at the Congressional Republicans who had run the previous year on a promise to fiscally hobble the Obama administration. The following year, after partisan redistricting disenfranchised the majority of North Carolina’s voters, more than 100,000 religious progressives and allies created the “Moral Mondays” movement against cuts to unemployment benefits and education, $2 billion in tax relief to the state’s highest earners, and refusal of the Medicaid expansion offered by the federal Affordable Care Act to 500,000 uninsured North Carolinians. As the movement spread, the refrain “Our state budget is a moral document” was echoed in Atlanta, Nashville, Jacksonville, and Albuquerque, and every state-level mobilization made the connection between wealth-hoarding and the voter suppression turbocharged by the 5-4 Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder in 2013.6

The scale mattered: state budgets specifically became battlegrounds for competing moral visions. In statehouses newly freed from national oversight, Jim Crow and Juan Crow mechanisms of disfranchisement roared back from decades of forced containment by Section 4(b), Article Five of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The rule at stake, which required jurisdictions with a proven antipathy to majority rule to submit to federal review any plans to enact new voting regulations, had been in Republican crosshairs since the Nixon administration, and in the twenty-first century had steadily restricted ballot access with new voter ID laws. Shelby County v. Holder put wind in the sails of GOP efforts to restrict even the thin procedural democracy of elections. Shedding preclearance meant making good on conservative strategist Paul Weyrich’s frank admission to a white evangelical audience in 1980: “I don’t want everybody to vote,” the co-founder of the Moral Majority, the Heritage Foundation, and the American Legislative Exchange Council explained in 1980 to listeners that included Phyllis Schlafly, Pat Robertson, and candidate Ronald Reagan. “As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.” Freed to discriminate in the name of color-blindness—a formula first prototyped by the 1890 Mississippi state constitution—much of the former Confederacy moved decisively to de-democratize state legislatures and amplify disproportionate white rural representation into the Electoral College, the Supreme Court, and Congress. They were aided especially in the Senate’s gross malapportionment by the slave-holders’ veto, the filibuster. In what was surely an unselfconscious echo of Weyrich, President Trump explained to Fox & Friends how he had shut down plans to expand voting access during the pandemic: “The things they had in there were crazy. They had things, levels of voting that if you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.”7

Implicitly or explicitly, questions of distribution, extraction, care, labor, production, reciprocity, and subsistence rest upon moral assumptions: what is fair, who owns, who owes, who makes, who takes, what is work, and what—who—is property. Just as inescapably, the various norms that compete to govern affect, kinship, sexuality, claims, coercion, or captivity require particular orderings of resources and obligations. Both “economics” and “ecology,” as sociologist Nathan Hare noted, incorporate the Greek root for “household”—the place we live and the human relations that sustain it. The house, like the plantation, pioneered the techniques of the factory and served as a prison labor camp for generations of Black women. It is somebody’s site of respite because it is somebody else’s site of coerced labor—or of affective attempts at domestication, as literary scholar Jordan Taliha McDonald brilliantly explores in these pages. It is also a security for debt or an asset for inheritance, a unit of consumption, a claim on the stratified resources of a school district or a water system. By some reckonings, the recent lurch toward right-wing authoritarianism owes much to the 2008 financial crisis, to the genesis of the Tea Party in an impassioned onscreen rant against—not the banks lining up yet again for the bailouts their models assume, but the “losers” left holding the bag. The “subprime” named a racial subject of “predatory inclusion” into the vast casino of speculative finance. “What is it,” asked scholars Paula Chakravartty and Denise Ferreira da Silva, “about blackness and Latinidad that turns one’s house (roof, protection, and aspiration) and shelter into a deathtrap?”8

In this issue of Southern Cultures, contributors reveal the moral dimensions of economic visions, and vice versa. Southern cultural traditions are the indispensable tools for producing this knowledge. The late geographer Clyde Woods theorized the blues as a “theory of social and economic change . . . a critique of plantation social relations” across time as well as an “aesthetic tradition”—an interpretation that inspires Brian Williams and Donald Mayfield Brown in their essay on abundance in the plantationocene. Quoting Franklin Rosemont, the poet and former editor of the anarchist journal Rebel Worker, Woods invokes the blues’ essential “subversive core,” its “aggressive and uncompromising assertion of the omnipotence of desire,” its affirmation of abundance against the “shameful limits of an unlivable destiny.”9

The scandal of manufactured scarcity is the recurring moral perversity at the heart of southern political economy. Surveying the human misery of the 1930–31 drought in the Delta, a relief worker reflected that those not directly affected could not imagine “‘people could hunger with the bountiful soil immediately underfoot.’” (“Five cent cotton, forty cent meat,” ran Bob Miller’s 1932 hit, “How in the hell can a poor man eat?”) Manufactured scarcity is also the central paradox Alex Beasley explores in the context of Texas’s energy economy. Since provisioning for the future is a poor path to profit, hundreds of Beasley’s fellow Texans perished in Winter Storm Uri when the electricity grid failed. “[S]carcity itself,” writes Beasley, “was a tactic rather than a problem,” a “political choice” for short-run profit through deregulation that bore no relation to the actual abundance. Gratuitous cruelty becomes a form of surplus value that cannot be captured by economic logic alone.10

“The Cruelty Is the Point” became one of the most widely circulated memes for the Trump era, thanks to a bestselling book by journalist Adam Serwer. Serwer argued chillingly that the opportunities for collective jeering, tormenting, and laughing at the pain of designated outsiders—at stealing money from the descendants of the enslaved in order to build a volleyball stadium, at serving up tax cuts while lead-laced raw sewage dribbles from taps in the capital—are the necessary adhesive for these political formations, the same kind of social glue that animates group violence. Experts on right-wing, organized racism have also argued that this kind of joy in pain, this kind of deliberate invitation to membership through cruelty, is an explicit goal of those who anticipate overt race wars over resources on a hot, crowded, barren planet: mocking disability, caging children, attacking the unhoused, plundering public resources are, in effect, training racially defined cadres to defend ownership claims to critical resources like land and water. According to this analysis, then, cruelty is a feature, not a bug, and must be cultivated actively in order to build social and political cohesion.11

Despite its trademark irrationality, its perverse glee, and even its conspiratorial bleeding edge, this authoritarian vision of white dominion arises from within economic logic itself. It is “a form of moral life that has embraced the compensatory logic of capitalist power to such an extent that the possibility of externalizing anxiety and assigning blame has come to assume a utopian quality,” argues political economist Martjin Konings. Within this cultic logic, the market is imagined as a perfect moral sorting device, “a decentralized coordination mechanism that ensures that people get what they deserve,” a faith so fierce that it “induces a certain fanaticism that breaks out of the bounds of civilized public debate.” And it is marked, argues historian Nancy MacLean, by its southern nativity: The dominant economic logic of the last half-century—the “quest to free capital of social obligation and political constraint” by “reduc[ing] everything to a commodity”— generalized to the nation and the world the political economy of the plantation.12

A budget is indeed a moral document—and so is a bank charter, a labor contract, a subprime mortgage, a furnishing ledger, a slaving ship’s manifest, an insurance policy, a stock quote, a corporate prospectus, an algorithm. The arid abstraction of “economics” relentlessly flattens this complexity into two dimensions and reduces people to hands, cypress swamps to timber and turpentine, mountains to coal pits, bayous to oil wells, wetlands to plantations. Claiming the mantle of positive science, it disavows its unbroken history of norm-making and even theology: Sir William Petty theorized both statistical tools of governance and a biologized racial hierarchy in his precise idiom of “political arithmetic.” Adam Smith, professor of “moral philosophy,” learned from his Scottish Presbyterianism that God laid upon Man as a sacred duty the “‘lawful procuring and furthering the wealth and outward estates of ourselves and others.’” In the early decades of the nineteenth century, his new discipline was elaborated by the Christian political economists of England and Scotland who saw in the Irish famine the righteous judgment of God; it was institutionalized in American academe by a corresponding generation of Protestant clerics. Their southern colleagues defended both Smithian free trade and Biblical pro-slavery arguments from the colleges and universities of Virginia, South Carolina, and Louisiana, while evangelicals in the lower Mississippi River valley advocated re-opening the trans-Atlantic traffic in humanity with the braided arguments of Christian political economy. Two decades after the Civil War, the American Economics Association was founded in the name of the Social Gospel. Even as twentieth-century economics shed its vaguely feminine associations with sanctity and claimed instead the manly status of a science, its theorists were never more than a breath away from purely faith-based claims—claims to the miracle of perpetual growth, to the sublimity of a “spontaneous order” that passeth human understanding, to the salvific power of techno-solutions and the millennial rapture of creative destruction.13

By contrast, the notion of “moral economy” demands “a fully loaded cost accounting,” in the words of historian Nell Irvin Painter. It acknowledges the abundance of resources with which people identify the just and the generous—and nowhere more than in the South. The Guatemalan-born promotoras of Mississippi’s chicken-processing towns responded to the largest workplace immigration raids in US history by creating mutual aid networks, which have since served their communities during the pandemic and the Jackson water crisis. In the campaign to decriminalize sex work in New Orleans, Women With a Vision offers the intertwined history of the Crescent City’s economies of music, dance, and sex, and invokes the foremothers of Storyville as well as the Q’uran, the Psalms, and the Afro-Brazilian spirit Pomba Gira, while the interfaith marches of Historic Thousands on Jones Street demand Medicaid expansion from the North Carolina legislature. For its model of a “solidarity economy”—worker-owned co-ops, credit unions, sustainable housing, land trusts, participatory budgeting—Cooperation Jackson draws on the heritage of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, Fannie Lou Hamer’s Freedom Farm, and Tanzanian Ujamaa, and it claims access to the arts as a human right. In the depths of both Jim Crow and the Great Depression, Robin D. G. Kelley found, American radicalism was defined by the prophetic Christianity that drew Black southern workers to the Communist Party: “‘Comrades, praise God for Lenin and them!’”14

In this lopsided struggle to assemble moral economies in the ruins of neoliberalism, we are pathetically dependent on artists and adepts. When the artist Dread Scott and his hundreds of collaborators staged the “Slave Rebellion Reenactment” along the 1811 route of the largest such revolt against slave labor camps in US history, they proclaimed liberty under the looming profiles of Louisiana’s deeply subsidized and deadly poisonous petrochemical plants. The landscape they disrupted has been the site, of course, of far more heavily capitalized acts of imagination: in 1978, a Louisiana court projected the American Petroleum Institute’s vision of moral economy into jurisprudence and, ultimately, national economic policy by way of “cost-benefit analysis.” The argument that was to ground an entire wave of deregulation envisioned the world as a giant ledger: if workers exposed to the known carcinogen benzene at a petrochemical plant were dying of leukemia at an elevated rate, and everyone agreed that lessening their exposure to benzene would lessen each individual’s risk, but no one could say by exactly how much, then the potential benefit to workers could not be weighed against the cost to the factory of mitigating exposure. In the interests of actuarial precision, therefore, the workers had to wait a decade until their risk could be more accurately quantified in economists’ terms. An estimated two hundred more workers died of leukemia in that interval. Using the measure of Discounted Future Earnings to quantify the lives at stake in cost-benefit defenses made the violence of the economists’ measure crystal clear: a dead homemaker was technically worth nothing, since she was not paid for her work, and the death of a disabled child could be valued as a net savings.15

The power of the ledger to assign valuation to human lives is the foundational story of the South itself—of Mississippi, and therefore America, in Malcolm’s X’s terms. Plat books sliced populated landscapes into vacant parcels for sale, securitization, and the extraction of millennia of accumulated productive capacity. Other neatly lined grids superimposed relations of ownership over relations of kinship, the material traces of “a racial calculus and a political arithmetic” by which “black lives are still imperiled and devalued.” By drawing the nation’s southern border, the slaveholders who helmed American foreign policy arbitraged the relative economic value of the people on either side of it, a platting that echoes through Iliana Rodriguez’s article in this issue.16

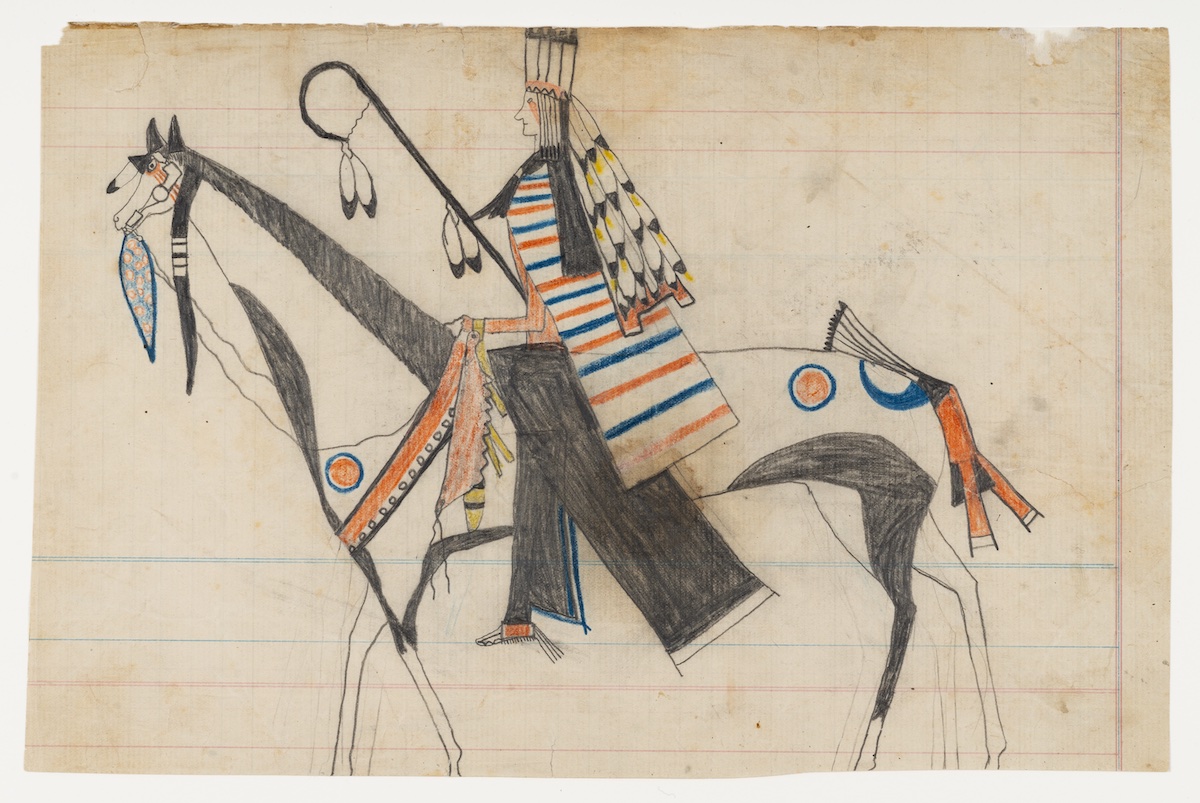

But the technologies of mapping, bookkeeping, and securitization that combined to flatten the physical world into fungible credits and debits can never contain the reality they purport to represent. Repurposing the paper ledgers lined and bound to record land dispossession, debts, and other transactions of the settler-colonial economy, nineteenth-century Native artists of the Southern Plains instead covered the columns with drawings in the style used to decorate tipi covers and buffalo hide robes: renderings of horses, of heroic feats, of courtship and dancing and feasts—“literally writing over the enemy’s economic balance sheet.” In canonizing the form, writes literary scholar Melanie Benson Taylor, art historians emphasize the images’ power as a medium of resistance. “[M]ost scholars of ledger art see the paper itself as an ideological battlefield,” she writes. Yet,

what the ledger itself actually introduces . . . is an opportunity to cathect complicated anxieties and ambivalences already simmering in the cultural body—one where the damage of the ledger had been irrevocably wrought long before these outcries against its tyranny . . . the instrument of the ledger itself matters, as a material force to be reckoned with and not simply reckoned away.

Taylor cautions us, in other words, not to mistake artistic transformation for escape from the grid itself. To refuse on the ledger’s claims to represent is not to deny its structuring power. It is, perhaps, to demand that accounting’s first responsibility is to give an account of itself to its objects—that it submit to an audit by poets who once were property.17

This essay introduces the Moral/Economies Issue (Winter 2022), guest edited by the authors.

Bethany Moreton is a grateful product of Mississippi’s public schools and libraries and a professor of history at Dartmouth College. She co-founded Freedom University Georgia. She is the author of Perverse Incentives: Economics as Culture War (forthcoming 2023); Entre Dios y el Capital; and To Serve God and Walmart.

Pamela Voekel is associate professor of history at Dartmouth College. She co-founded Freedom University Georgia; the Tepoztlán Institute for the Transnational History of the Americas; the Patrona Collective for Colonial Latin American Scholarship; and the Mississippi Freedom Writers. She is the author of Alone Before God: The Religious Origins of Modernity in Mexico and For God and Liberty: Catholicism and Revolution in the Atlantic World, 1790–1861.

NOTES

- How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton, ed. Aracelis Girmay (Rochester, NY: BOA Editions Ltd., 2020), 19; and see Joshua Bennett, Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674245495; O’Brien quoted in E. P. Thompson, Customs in Common (London: Merlin Press, 1991), 337. Emphasis in the original. Thompson cites this as the first occurrence of the term which he reintroduced into historical writing in his landmark article “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century,” Past & Present 50, no. 1 (1971): 76–136. The concept gained even greater traction in economic sociology after political scientist James Scott analyzed the “notion of economic justice” and the “working definition of exploitation” that informed the “safety first” subsistence ethic of farmers in Southeast Asia, a then-contemporary counternarrative to the assumptions of profit-maximizing economic man. Scott, The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976); Malcolm X, “What Does Mississippi Have to Do with Harlem?” 1964, http://www.shoppbs.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/eyesontheprize/sources/ps_noi.html; “About” page, official website of US Congressman Bennie Thompson, https://benniethompson.house.gov/about.

- Amanda Klasing, “Mississippi Water Crisis a Failure Decades in the Making,” Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/09/02/mississippi-water-crisis-failure-decades-making; Ashton Pittman, “Gov. Reeves Signs $524-Million Tax Cut As Education, Infrastructure Funding Woes Remain,” Mississippi Free Press, April 6, 2022, https://www.mississippifreepress.org/22641/gov-reeves-signs-524-million-tax-cut-as-education-infrastructure-funding-woes-remain; Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves quoted in Kayode Crown, “Gov. Reeves Vetoes Jackson Water Bill, More Paving, Mask Requirement Ahead,” Jackson Free Press, June 30, 2020, at https://www.jacksonfree-press.com/news/2020/jun/30/gov-reeves-vetoes-jackson-water-bill-more-paving-m/.

- Immigrant Action for Justice and Equity, “El Gobierno Quiere Privatizar el Sistema de Agua Jackson; La Communidad Debe Decir Que No!,” Facebook, September 28, 2022, accessed October 8, 2022; Molly Minta, “‘What’s Next, the Air?’ Local Activists Push Back on Local Plans to Privatize the City Water System,” Mississippi Today, September 15, 2022, accessed October 8, 2022; Nick Judin, “Under the Surface, Part 3: A Water Crisis Amid a Legacy in Decline,” Mississippi Free Press, April 21, 2021, https://www.mississippifreepress.org/11498/under-the-surface-part-3-a-legacy-in-decline; accessed October 2, 2022; Michael Goldberg, “Mississippi Governor, Who Opposed Water System Repairs, Blames Jackson for Water Crisis,” PBS Newshour, September 27, 2022, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/mississippi-governor-who-opposed-water-system-repairs-blames-jackson-for-crisis#, accessed October 8, 2022; Seyma Bayram, “The Siemens Settlement, Explained,” Jackson Free Press, March 4, 2020, https://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2020/mar/04/siemens-settlement-explained/, accessed October 2, 2022; having sued Siemens for $450 million in damages, the city settled with the company for $89.8 million in 2020.

- Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, Getting Tough: Welfare and Imprisonment in 1970s America (Princeton: Preinceton University Press, 2017); Jill Quadagno, The Color of Welfare (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Loïc Wacquant, Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009); Lily Geismer, Left Behind: The Democrats’ Failed Attempt to Solve Inequality (New York: PublicAffairs, 2022).

- Ashton Pittman, “Ex-Mississippi Welfare Leader Pleads Guilty to Federal, State Crimes in Exchange for Cooperation,” Mississippi Free Press, September 21, 2022, https://www.mississippifreepress.org/27551/ex-mississippi-welfare-leader-indicted-on-federal-conspiracy-fraud-charges; Jimmie E. Gates, “MDHS Confirms Most New Applicants Rejected for Welfare,” Jackson Clarion-Ledger, April 20, 2017, https://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/2017/04/20/mdhs-confirms-most-new-applicants-rejected-welfare/100692926/. The quoted figures are for 2016; Melissa Alonso and Dianne Gallagher, “Former official pleads guilty in welfare fraud scheme where money was funneled to prominent Mississippians including Brett Favre,” CNN.com, September 23, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/09/22/us/mississippi-john-davis-welfare-fraud-guilty-plea/index.html; on Mississippi’s tax structure, which leaves income more unequal after taxes than before, see Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Mississippi: Who Pays?,” October 17, 2018, https://itep.org/whopays/mississippi/. The electoral rules established in the state’s 1890 constitution were explained with refreshing frankness by one of its framers, legendary white supremacist governor James K. Vardaman: “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter,” Vardaman asserted. “Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the [African American citizen] from politics.” Vardaman quoted in Jerrold M. Packard, American Nightmare: The History of Jim Crow, 1st ed. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002), 69. While many of the white supremacist mechanisms were invalidated under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, one such rule remained in effect until amended in a statewide ballot measure in 2020. See Lawrence Goldstone, “America’s Relentless Suppression of Black Voters,” New Republic, October 24, 2018; Matt Ford, “Mississippi Quotes John Roberts to Defend Its Racist Election Law,” New Republic, July 19, 2019; Ian Millhiser, “How a Jim Crow Law Still Shapes Mississippi’s Elections, Vox, October 11, 2019 [updated Nov. 5, 2019], https://www.vox.com/2019/10/11/20903401/mississippi-jim-crow-law-rig-election-electoral-college-jim-hood-tate-reeves; Mississippi Center for Justice, “MS Legislature Proposes Constitutional Amendment to Repeal Discriminatory Election Scheme from 1890 Constitution,” June 30, 2021, https://mscenterforjustice.org/1605-2/.

- David Gilgoff, “New Campaign Asks ‘What Would Jesus Cut?,’” CNN Belief Blog, February 28, 2011, at https://religion.blogs.cnn.com/2011/02/28/new-budget-campaign-asks-what-would-jesus-cut/. The final package cut $38 billion.

- The capacity for the modern GOP to control all branches of the federal government without winning a majority of votes has been amply demonstrated in the twenty-first century. Most dramatically, between 2017 and 2021, more than 220 judges, including three Supreme Court justices, were appointed by a president who lost the popular vote and confirmed by a Senate that a majority of voters didn’t choose. Laura Bronner and Nathaniel Rakitch, “Advantage GOP,” FiveThirtyEight, April 29, 2021, at https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/advantage-gop/. On the filibuster, see Emmet J. Bondurant, “The Senate Filibuster: The Politics of Obstruction,” Harvard Journal on Legislation 48 no. 2 (2011): 467–513; Catherine Fisk and Erwin Chemerinsky, “The Filibuster,” Stanford Law Review 49, no. 2 (1997):181–254; Samuel L. Perry, Andrew L. Whitehead, and Joshua B. Grubbs, “‘I Don’t Want Everybody to Vote’: Christian Nationalism and Restricting Voter Access in the United States,” Sociological Forum 37, no. 1 (2022): 4–26, https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12776; direct quotations from pp. 9–10. For an overview of minority rule at the federal level, see Adam Jentleson, “How to Stop the Minority-Rule Doom Loop,” The Atlantic, April 12, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/04/how-stop-minority-rule-doom-loop/618536/.

- Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016); Arun Gupta, “The Rant Heard Round the World,” The Public Eye, August 1, 2011, https://politicalresearch.org/2011/08/01/tea-party-new-populism; Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019); Paula Chakravartty and Denise Ferreira da Silva, “Accumulation, Dispossession, and Debt: The Racial Logic of Global Capitalism—An Introduction,” American Quarterly 64, no. 3 (2012): 367.

- Clyde Adrian Woods and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta, 1st paperback ed. (New York: Verso, 2017), 38–39.

- Red Cross worker quoted in Alison Collis Greene, No Depression in Heaven: The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta(New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 27; Bill C. Malone and Tracey E. W. Laird, Country Music USA, 50th anniversary ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 57. Miller evidently cribbed the original 1928 recording “Eleven-Cent Cotton” from verses by Mrs. S. C. Ford of Frisco, Texas, that were reprinted in multiple newspapers across Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Arkansas during the agricultural depression gripping the Southwest in the wake of World War I; it dropped to “Seven-Cent Cotton” before the 1932 version bottomed out at “Five-Cent Cotton.” The meat, in contrast, held steady at forty cents. Tony Russell, “‘Eleven Cent Cotton Forty Cent Meat’—Parts 1 and 2: Bob Ferguson [Bob Miller] Columbia 15297-D,” Rural Rhythm: The Story of Old-Time Country Music in 78 Records (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), online edition, Oxford Academic, https://doi-org.dartmouth.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/oso/9780190091187.003.0030; accessed October 2, 2022.

- Adam Serwer, The Cruelty Is the Point: The Past, Present, and Future of Trump’s America, 1st ed. (New York: One World, 2021).

- Martijn Konings, “Imagined Double Movements: Progressive Thought and the Specter of Neoliberal Populism,” Globalizations 9, no. 4 (August 2012): 617, https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2012.699939. Konings is quoting from Walter Benjamin; Martjin Konings, “Neoliberalism Against Democracy?: Wendy Brown’s ‘In the Ruins of Neoliberalism’ and the Specter of Fascism,” Los Angeles Review of Books, September 22, 2019, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/neoliberalism-against-democracy-wendy-browns-in-the-ruins-of-neoliberalism-and-the-specter-of-fascism/; Nancy MacLean, “Southern Dominance in Borrowed Language: The Regional Origins of American Neoliberalism,” in New Landscapes of Inequality: Neoliberalism and the Erosion of Democracy in America, ed. Jane Lou Collins, Micaela Di Leonardo, and Brett Williams (Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press, 2008), 21–37.

- Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic and the Re-enchantment of Humanism: Suffering and Infrahumanity, Tanner Lectures on Human Values, ed. Mark Matheson (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2016), 34–5; “lawful procuring and furthering the wealth and outward estates of ourselves and others” is the language that the Shorter Catechism of the Westminster Assembly uses to explain the Eighth Commandment, and which Smith memorized in his Presbyterian childhood. A. M. C. Waterman, “Moral Philosophy or Economic Analysis? The Oxford Handbook of Adam Smith,” Review of Political Economy 27, no. 2 (April 2015): 223; Eugene McCarraher, The Enchantments of Mammon: How Capitalism Became the Religion of Modernity (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019), 50–58; Stewart Davenport, Friends of the Unrighteous Mammon: Northern Christians and Market Capitalism, 1815–1860 (University of Chicago Press, 2008); Jay R. Carlander and W. Elliot Brownlee, “Antebellum Southern Political Economists and the Problem of Slavery,” American Nineteenth Century History 7, no. 3 (September 2006): 389–416, https://doi.org/10.1080/14664650600956585; John Lindbeck, “Slavery’s Holy Profits: Religion and Capitalism in the Antebellum Lower Mississippi Valley” (ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2018), https://search.proquest.com/docview/2063148500?pq-origsite=primo; Bradley W. Bateman and Ethan B. Kapstein, “Retrospectives: Between God and the Market: The Religious Roots of the American Economic Association,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 13, no. 4 (1999): 249–58, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.13.4.249; see Bethany E. Moreton, Perverse Incentives: Economics as Culture War (Near Futures, Princeton University Press, forthcoming 2023).

- Nell Irvin Painter, Soul Murder and Slavery, Charles Edmondson Historical Lectures 15 (Waco, TX: Markham Press Fund, Baylor University Press, 1995); Robin D. G. Kelley, “‘Comrades, Praise Gawd for Lenin and Them!’: Ideology and Culture among Black Communists in Alabama, 1930–1935,” Science & Society 52, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 59–82. As Kelley explains, the title is slightly paraphrased from an interview with the legendary labor radical Hosea Hudson.

- Dread Scott, “Slave Rebellion Reenactment,” https://www.slave-revolt.com/; Grégoire Chamayou, The Ungovernable Society: A Genealogy of Authoritarian Liberalism, trans. Andrew Brown (Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2021).

- Jennifer L. Morgan, Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021); direct quotations from Saidiya V. Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 6; Matthew Karp, This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016)

- Schild Ledger Book, Blanton Museum, University of Texas, https://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/spotlights/ledgerart/ledger-art.html; Melanie Taylor Benson, “Unsettling Accounts: The Violent Economies of the Ledger,” in Ledger Narratives: The Plains Indian Drawings of the Lansburgh Collection at Dartmouth College, ed. Colin G. Calloway and Hood Museum of Art (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012), 191.