When Joshua Clark Davis and Seth Kotch began work on the Media and Movement project on behalf of the National Endowment for the Humanities and Southern Oral History Program at UNC–Chapel Hill, their starting place was easy: Durham’s WAFR. WAFR was the nation’s first public, community-based Black radio station, and, as Davis notes, “also the first, if not the only, radio station in America devoted to advancing the goals of the Black Power movement.” WAFR’s inspiration and intent was always right in its call letters. As Obataiye Akinwole, one of the station’s founders and managers described in the 1995 documentary Black Radio: Telling It Like It Is, “We wanted to have our heritage in our name.”1

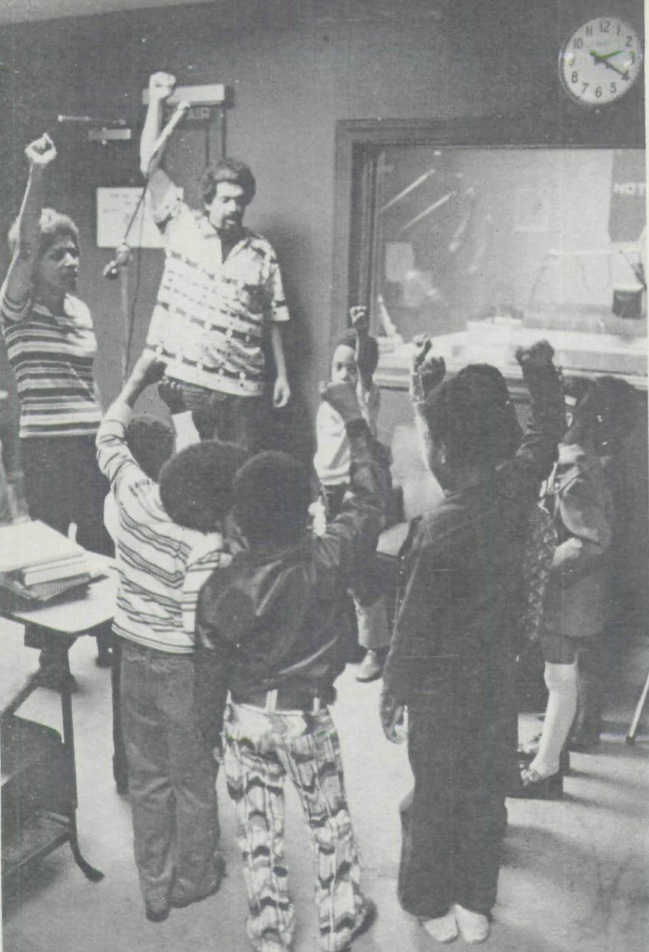

In 1973, writer Carolyn Erwin traveled to Durham to cover WAFR-FM for Ebony magazine. “When she arrived at 336 ½ East Pettigrew Street, she found a radio station like no other in America,” Davis wrote for the Durham History Museum. “In one room of the station, two teachers and a group of five-year-olds chanted in unison, ‘I am a black and proud warrior dedicated to the liberation of all black people. I recognize Africa as the motherland and her people as my people.’ In another room, local theater director Karen Rux guided teenagers as they produced their own radio show called Black Seeds. Jazz and African music drifted from the control booth, peppered with announcements from deejays [including] Obataiye Akinwole and Shanga Sadiki.”2

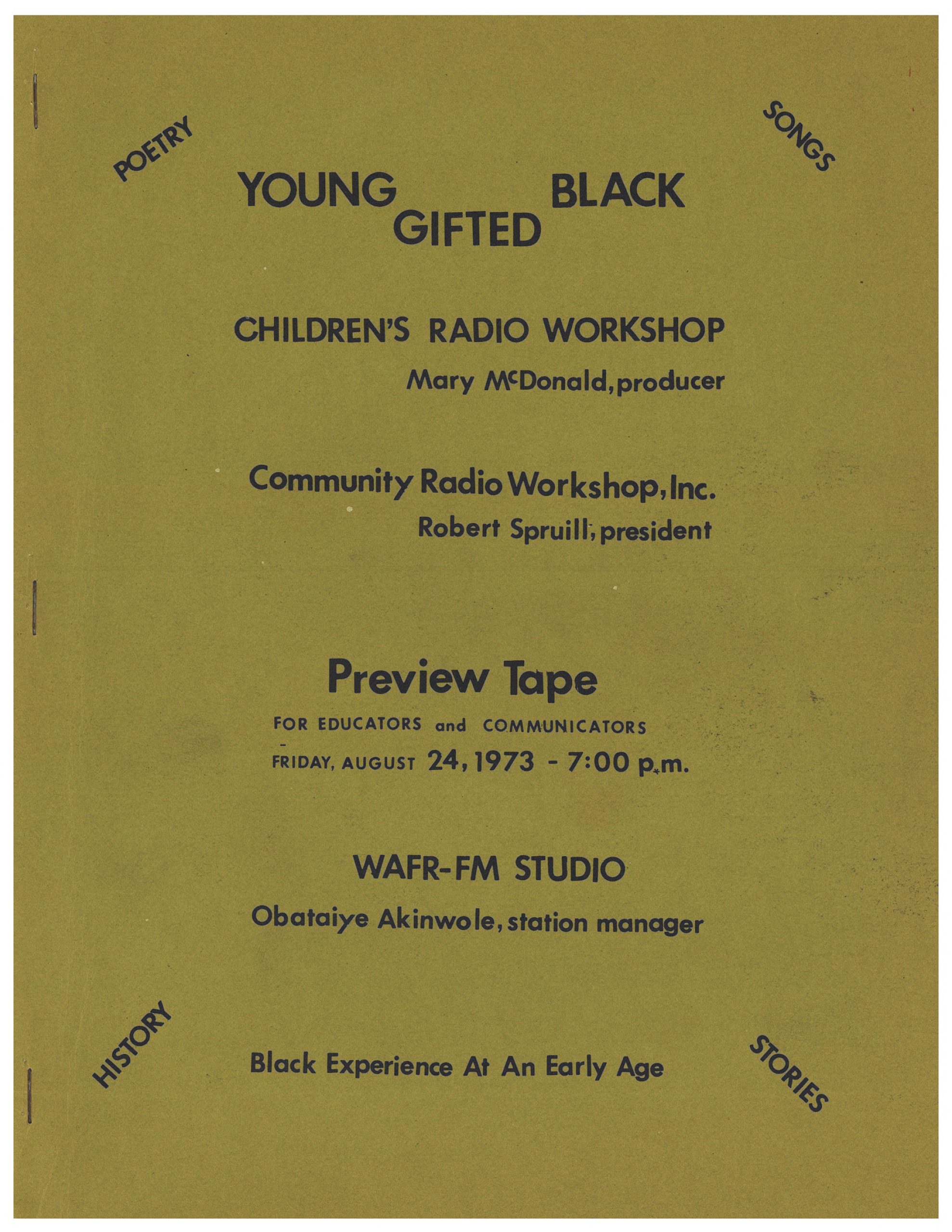

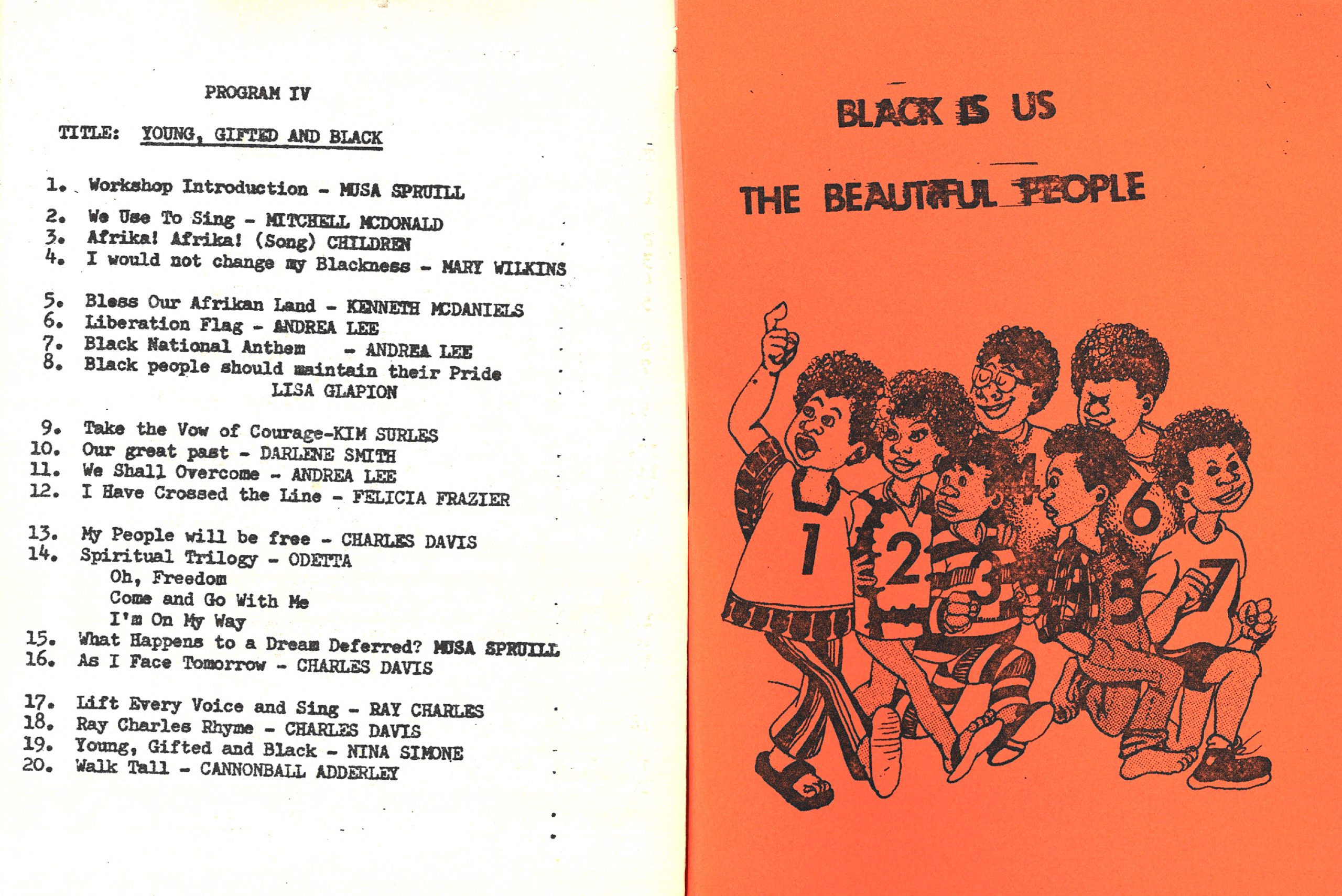

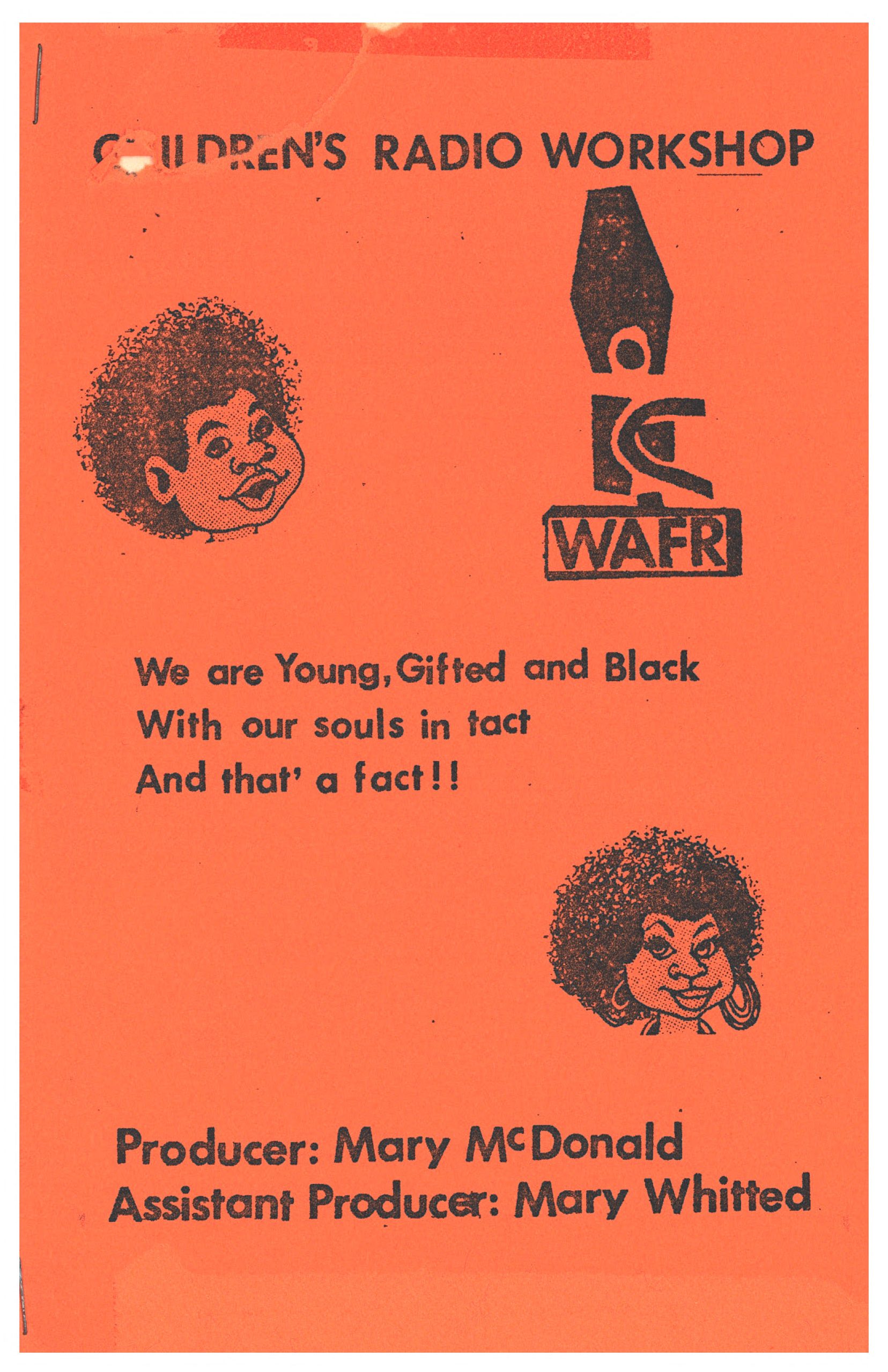

Over the course of its five-year run, WAFR offered Black residents of North Carolina something radical and wonderful. As Media and the Movement describes, WAFR was a “politically engaged, Black Power programming that included jazz, funk, African music, selected local and national news, and even an African American take on Sesame Street”—the Children’s Radio Workshop. Offering programming for children was of particular interest to Akinwole and his collaborators. He says the Children’s Radio Workshop was a way of saying “to Black kids: You can do this. You can be a cameraperson, you can be a director, you can be an online announcer, any of these possibilities, you can be that, right? You can be a filmmaker.”3

I connected with Akinwole at an exceptionally fortuitous moment in late July, seven years after Media and the Movement ceased gathering materials. Akinwole told me he had been steadily cleaning out his attic, preparing to discard some remaining WAFR paperwork he’d come across stashed in a USPS Priority Mail box. Inside was a veritable treasure trove: programs and programming calendars for the Children’s Radio Workshop, missives between station managers, budget reports, letters of appreciation (from members of Congress to HBCU students), and copies of hand-drawn illustrations, poems, and songs.

Over the course of its five-year run, WAFR offered Black residents of North Carolina something radical and wonderful.

Many of those materials are published here, alongside eight episodes of the Children’s Radio Workshop, available for accessible public listening for the first time. Together, they offer an intimate glimpse into what could reasonably be considered the heart and soul of WAFR. They are a thing of beauty. There is no condescension, no hiding from difficult topics. The narrators, guests, and child performers treat every moment on air as teachable; an opportunity to present Black culture and cultivate a love of Blackness without worrying about catering to or sanitizing materials for a white audience. The episodes cover an impressive range of topics: poetry, Black historical figures, self-love, motherhood, children’s folklore, Black power, pan-Africanism, Langston Hughes, and jazz. Every child included in an episode is credited alongside the words and music of established artists and performers featured underscoring the egalitarian nature of the station and program.

Episodes begin with Houston Person’s song “Young, Gifted, and Black” followed by a brief introduction. One of the first episodes preserved in the archives, originally aired in 1973, dedicated a half-hour to the writings, words, and musings of writer Toni Cade Bambara, who had traveled to Durham to support WAFR’s ’73 marathon by giving readings at North Carolina Central University. Announcer Mary McDonald “proudly salutes” Bambara and encourages listeners to “stay with us, for an evening of tales and stories for Black folks, edited by our most beautiful and gracious sister, Toni Cade Bambara.”

“Young, Gifted, and Black” transitions the broadcast into a chorus of young people reading Linda Holmes’s short story “The True Story of Chicken Licken,” which Bambara published in her 1941 anthology Tales and Stories for Black Folks. “The True Story of Chicken Licken” is, like many children’s stories, unabashedly straightforward in speaking truth to power. In this rendition, Chicken Licken is not struck by what appears to be a piece of falling sky, but rather a baton, wielded by a police officer. She has no trouble convincing her friends of the wrongdoing; it is the authorities who remain unmoved. Ultimately, police “convince the community that it was a piece of sky that fell on her poor little head and made her so anti-police.”4

“The True Story of Chicken Licken” flows into another retelling of a classic children’s tale, Bernice Pearson’s “The Three Little Brothers.” Though set in Newark, this version (much like the original—sans pigs) begins with brothers who can’t decide what sort of house to buy (wood, straw, or brick), “so they went their separate ways.” Here, the story diverges sharply from its inspiration: a rumor flies through the city that Black people, “sick of property being treated as more important than people,” planned to burn down the town. A riot breaks out which destroys the city and kills the brother living in the straw house (purposefully ignored by the presumably white fire department). The brother living in the wooden house flees to his brother in the brick home who opens his doors to all Black residents of the city “sick and tired of living in crummy houses.” This ending, read with relish, fades into Bill Withers’s “Lean on Me.” These kinds of morals and endings were typical for material read on the Children’s Radio Workshop. WAFR saw no reason to shield children from the realities of prejudice and racism entrenched in virtually every American institution. In this way, the Children’s Radio Workshop got much closer to the root of so many children’s folktales of old: honest, frequently brutal lessons. But this did not manage to overshadow the eclectic, upbeat, and ultimately hopeful nature of program on the whole.5

In the episode entitled “Living in Blackness,” a reading of Langston Hughes’s “Afro-American Fragment” (How far away is Africa / so far away is Africa) fades into a mournful, reflective rendition of “Amazing Grace.” When the host breaks the spell, she does so gently. “It does not matter anymore what the history books record—for we know the true facts,” she says evenly, “and we will write our own history. We have crossed over the threshold of the coming of a positive self-image. We have cultivated ourselves, and we have blossomed, like the first flowers of summer. But unlike the first flowers of summer, our positiveness will not die and wither away.”6

The episode ends with the same message repeated at the end of nearly every Children’s Radio Workshop broadcast: “Stay young, stay gifted, and stay Black.”

The Children’s Radio Workshop

Justine Orlovsky-Schnitzler is an abortion funder, reproductive justice worker, and writer currently at home in the South. She writes most frequently for Lilith Magazine and holds a B.A. in History and Women’s and Gender Studies and an MA in Jewish folklore, both from UNC-Chapel Hill.

- Media and the Movement: Journalism, Civil Rights, and Black Power in the American South, accessed April 26, 2022, https://mediaandthemovement.unc.edu/; Media and the Movement; Smithsonian Productions and Jacqueline Gales Webb, Black Radio: Telling It Like It Was, Archives of African American Music and Culture, Indiana University, SC 39, https://aaamc.indiana.edu/Collections/Black-Radio-Telling-It-Like-It-Was.

- Carolyn K. Erwin, “A Black Voice in Durham,” Ebony, June 1973; Joshua C. Davis, “Media and the Movement,” Museum of Durham History Blog, March 17, 2014, https://www.museumofdurhamhistory.org/blog/media-and-the-movement.

- Media and the Movement: Journalism, Civil Rights, and Black Power in the American South, accessed April 26, 2022, https://mediaandthemovement.unc.edu

- Karen Sands-O’Connor, “Power Primers: Black Community Self-Narration, and Black Power for Children in the US and UK,” Research on Diversity in Youth Literature 3, no. 1 (2021):12, 13.

- “A Salute to Toni-Cade Bambara,” The Children’s Radio Workshop.

- “Living in Blackness,” The Children’s Radio Workshop.