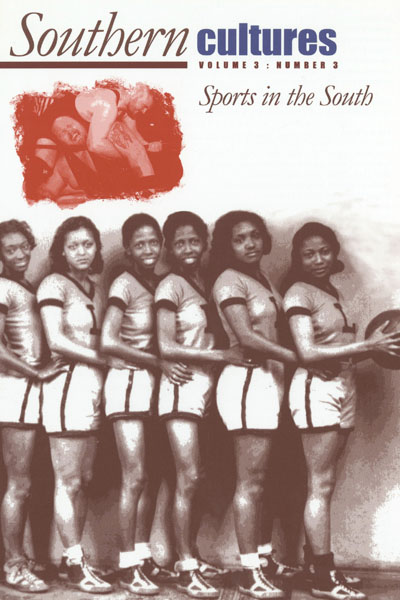

"Players should be dressed in clothing which is not only proper but attractive, and which will remain in place during the game."—Athletics for High School Girls, North Carolina College for Women, November 1925

It is the winter of 1997, and Tiffany Cummings plies the South Robeson High School basketball court, watched by a reporter who has traveled from the state capital to the tiny town of Rowland just to see her play. Cummings is the Mustangs’ star scorer, with a soft touch that mesmerized her coach the first time he saw her loft a shot in gym class, and launched him on a furious campaign to recruit her for the team. But the Raleigh News and Observer has not sent its writer on a hundred-mile trip because of Cummings’s hot three-point hand. Rather, it is for her dress. Instead of donning the blue and white shorts sported by her teammates, Cummings dribbles and shoots and drives to the basket wearing a skirt sewn by her mother, one which reaches modestly below her knees. Her father, a Baptist with a strict view of the Bible, has no trouble with his daughter playing ball, even if her energetic play does sometimes “knock people down.” But he will not let her appear in clothing “which pertaineth unto a man.”