In July 1993, Wanda and Brenda Henson bought a “defunct pig and grape farm” in Ovett, Mississippi. Brenda described the land as “right outside Hattiesburg, 77 miles from the Gulf Coast,” where they’d been living in Gulfport. Located on Bogue Homa Creek, the 120-acre property had “five barns and one house to be renovated” and cost the lesbian couple $60,000. Wanda was a native Mississippian from Pascagoula; Brenda, originally from Ohio, had lived in Mississippi since 1981. They met in May 1984 while volunteering as escorts at an abortion clinic, after both having left heterosexual marriages. Wanda and Brenda fell in love and later described themselves as married, taking the name Henson, Brenda’s mother’s maiden name. For the Hensons, Mississippi was home. And the inexpensive land in Ovett would fill their unflappable vision of building a lesbian and feminist community to serve the South.1

They named the Ovett property Camp Sister Spirit. And as they explained in a letter to Feminist Bookstore News in the fall of 1993, they planned for it to become a “feminist educational and cultural retreat center focusing upon the concerns of Southern Lesbians/Womyn.” They also intended to “rent the center to like-minded organization[s]” and a group of autonomous women “living on the land and caregiving the land and projects.” They were raising funds for the land by “leasing one acre land sites on a lifetime basis for $5,000.” Not long after buying the property, they had already leased eight acres with twelve remaining.2

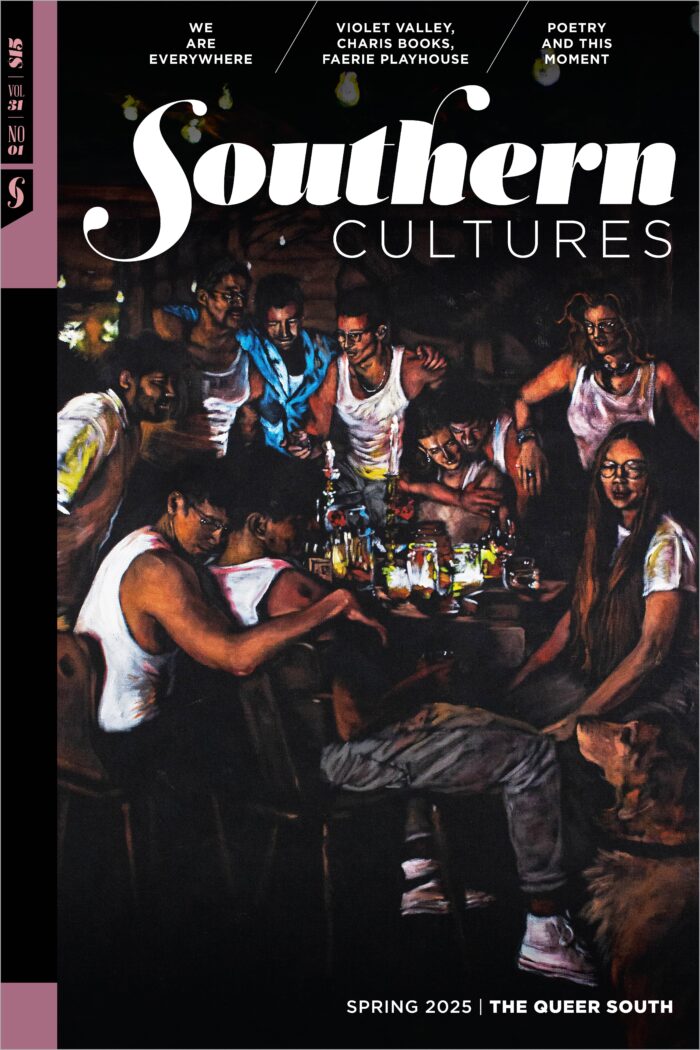

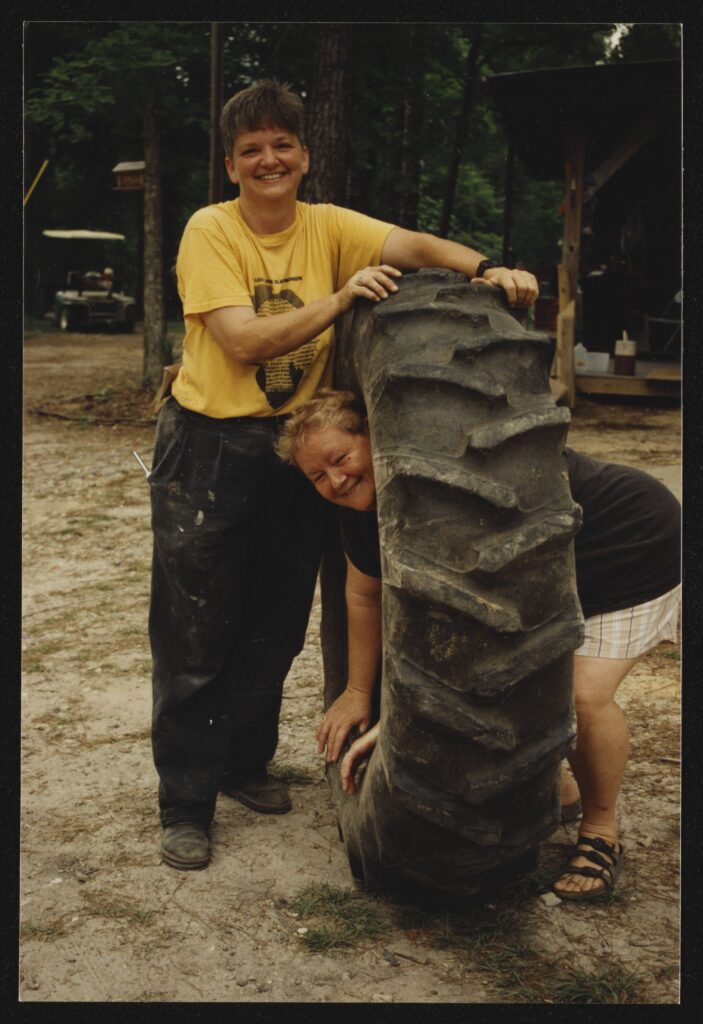

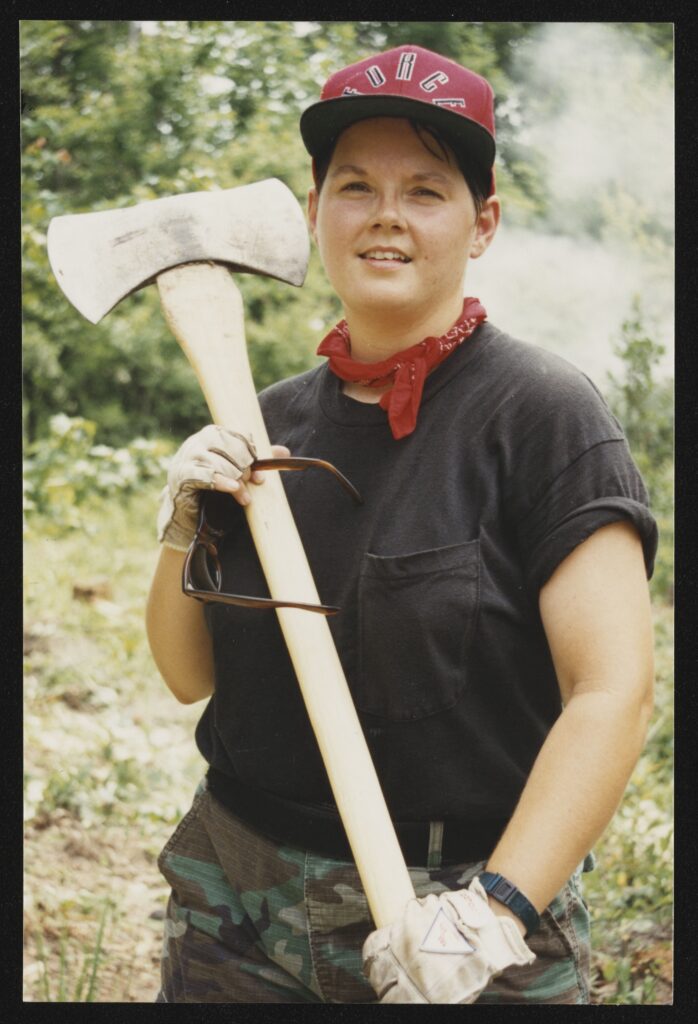

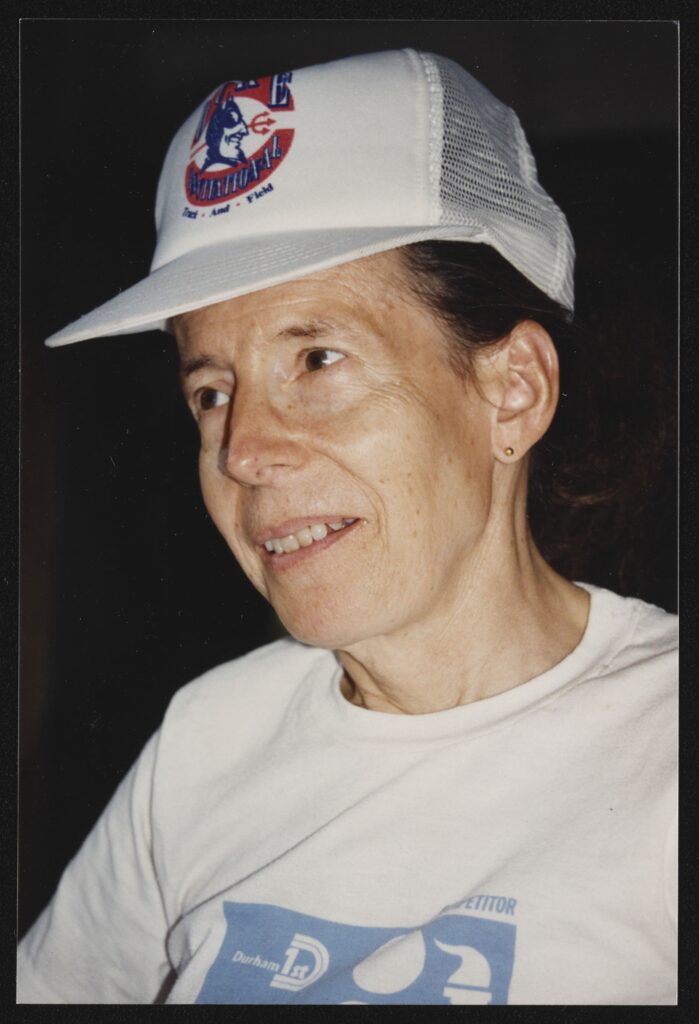

Top: Wanda (standing) and Brenda Henson at Camp Sister Spirit. Bottom: Three women at Camp Sister Spirit. All photographs from Camp Sister Spirit Photographs, Merle Hoffman Papers, Box PH-4, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

While the Hensons were spreading the word in national lesbian and feminist networks, local folks in Jones County, Mississippi, learned about the two women and their visions. Some were not happy about Camp Sister Spirit and made it known with chilling hostility and aggression. On November 8, 1993, while Brenda was out digging a ditch, her daughter discovered a “dead dog tied to their mailbox.” It “was a female, shot in the stomach, with tampons stuffed under its body.”3

A few weeks later, on Sunday, November 28, 1993, the local newspaper published the first op-ed by J. D. Hendry about the “lesbian retreat,” in which Hendry expressed his concerns “for my children, community, county and state.” According to him, local residents obtained a copy of The Grapevine, Camp Sister Spirit’s newsletter. In the op-ed, Hendry reported on Camp Sister Spirit’s plans to host a “Halloween Campout and Land Dedication” on October 30, 1993, with an open invitation for “Lesbians and women” along with “boys up to age eight years and all girls” to participate in the dedication. The Hensons also planned a Lesbian Conference for early December. Quoting from The Grapevine, Hendry noted it would “focus on building feminist lesbian community with non-oppressive lifeways.” To the women receiving the newsletter, such events were congruent with the vibrant lesbian-feminist festival communities and activities that operated nationwide. To outsiders, it sounded nefarious.4

Hendry expressed outrage that the Hensons had given “directions for how to reach Camp Sister Spirit from Mobile, Pensacola, New Orleans, and parts unknown,” insinuating that lesbians would be traveling to Ovett in droves and warning that “they will soon become a permanent fixture in our community.” Both sentiments are, of course, exactly what the Hensons hoped! They were building a space for a large music festival in the South and wanted to be a positive force in the local community. Hendry continued, “Our community is full of fine, Christian citizens, who welcome strangers with open arms, but I feel we must stop this lesbian colony from growing roots in our land and affecting the way we live our lives and rear our children. As it stands now, I am personally not ready to have South Mississippi turned into a haven for every stray lesbian that wants to settle down in Jones County!” He suggested that citizens should come together, “pool our resources and buy back our land.” He also encouraged the visitors “to keep heading north to New York or west to California.” “If they would relocate to a major metropolitan area,” he wrote, “I am sure they would be happier, and their Womyn’s Retreat would not feel like such an attack on our values and way of life.” In conclusion, Hendry offered, “I hope together we can find some logical, legal solution to rid our county of this blight to our land.” The op-ed served as the opening volley in what emerged as a heated public dispute among residents of Jones County. Contesting the use of the land at 444 East Side Drive in Ovett, Mississippi, played out on the pages of the Hattiesburg American, in county council meetings, with police interventions, and in conversations among residents in public and private. An Ovett resident identified as Harold told Peter Applebom of the New York Times, “These people don’t like queers, and if people in Ovett don’t want you here, you won’t be here very long.”5

Despite the conflict, Camp Sister Spirit and the Hensons became a significant part of queer Mississippi for more than a decade. Political scientist Kate Greene situated the conflict in Ovett using feminist theologian Mary Daly’s theorization of “sado-ritual syndrome.” With political scientist Edward M. Wheat, Greene described Camp Sister Spirit as part of “a long history of the search for alternative community in United States history” and an example of the tension between “individualism and communalism.” Camp Sister Spirit operated as an economic, political, and cultural organization in Mississippi enacting the values of lesbian-feminism expressed through cultural organizing. The conflict between Camp Sister Spirit and local communities demonstrates the intense opposition to lesbians in the early 1990s and how it dissipated with time, legal victories, and the tenacity of the Hensons. The story of Camp Sister Spirit and the Henson’s activism resonates today as book bans, rollbacks on Pride celebrations, and new anti-queer legislation antagonizes queer people, particularly in the South.6

Top: Roadside sign directing women to Camp Sister Spirit. Bottom: One entrance to the shared bunkhouse facilities.

“Can a Community Define Itself?”

About a week after Hendry’s op-ed in the Hattiesburg American, more than 250 Ovett residents gathered at the Lovett Community Center on Monday, December 6, 1993, “to discuss how the feminists might be driven away.” (Notably, Ovett’s population was around 300 at the time). According to Newsweek’s coverage, meeting attendees objected to Camp Sister Spirit “on religious grounds and concerns for the safety of the area’s young women” and began organizing their opposition to Camp Sister Spirit, agreeing to study state law and seek legal opinions before meeting again in January. Wanda and Brenda Henson and the women of Camp Sister Spirit did not attend the meeting but reported to the national media (and local police) harassing phone calls and “nightly shotgun blasts on the periphery of their scrubland property.” Brenda told Newsweek: “We have guns and we know how to use them. There are a lot of nervous women out here with trigger fingers.”7

Shortly after that meeting, the editorial board of the Hattiesburg American weighed in with an evenhanded call for residents to take a wait-and-see attitude with Camp Sister Spirit. They wrote on December 8, 1993, “Give Sister Spirit a chance. They haven’t done anything to harm anybody in Ovett.” The editorial continued, “These women have legally purchased this property and, so far as we know, have done nothing illegal. If they do, we have laws to deal with that. But you can’t just run people off their property because you don’t like them. This is America, the land of the free. We don’t need witch hunts here.” The language of the editorial, particularly “witch hunt,” suggested that greater hostilities existed below the surface, and it did nothing to prevent further hostility.8

The conflict escalated and continued to draw national attention. On Saturday, December 11, 1993, the Hattiesburg American reported that “four women from Camp Sister Spirit and three area men who oppose their existence in this rural community” will be on the Oprah Winfrey Show. The three opponents of Camp Sister Spirit were Paul Walley, a Perry County attorney from Richton, Rev. John Allen of Richton, and James Hendry of Ovett. According to Greene and Wheat, the Oprah Winfrey Show was the first time “both sides had met face to face,” but “it did nothing to advance or resolve the dispute.”9

Walley emerged as the spokesperson in mid-December with a harder line than expressed by Hendry. As quoted in The Clarion Ledger, Walley said, “As long as the focus of their existence is homosexuality, there’s no way we can meet in the middle with a lifestyle that is totally committed to sin. There’s no compromise there.” According to the same paper, Sheriff Maurice Hooks “cautioned opponents of the camp not to use violence.” He attended the meeting and said, “Regardless of what you think, they have rights, and we have to behave like Christians.” On Monday, December 20, the Jones County Board of Supervisors meeting included conversations about Camp Sister Spirit. The Hattiesburg American reported that the Supervisors “voted unanimously to ask the county attorney to research opponents’ claims and to report back at the next meeting in January.” The Oprah Winfrey Show aired nationally on Tuesday, December 21, 1993.10

In early January, local newspapers announced Walley’s plans to sue Camp Sister Spirit on behalf of local property owners. And on Monday, January 3, more than 400 people met at the Jones County Courthouse to oppose the Hensons and Camp Sister Spirit. Hostility and harassment increased as opposition became more organized. Henson reported to the Clarion-Ledger that “we had a death threat Christmas night, and my caller I.D. caught them . . . It feels more tense, and I think it’s grown to a mob mentality.”11

Over the next six months, the Hensons and other women at Camp Sister Spirit endured a range of harassments, threats, and frightening aggressions from neighbors. As early as December 1993, Wanda expressed the desire to meet with US Attorney General Janet Reno “about attempts to oust her group from its Jones County home.” Wanda was quoted in the Hattiesburg American saying, “When you see a community of townspeople, which is composed of politicians, ministers and spokespeople, rise up and decide to have a town meeting so they can oust anybody from their town, their community, this is what is called governmental repression.” She continued, “As a United States citizen, I have a right for officials not to do what they did in that meeting.” Reports included the county sheriff passing the hat to raise money for a lawsuit to drive the Hensons out of town. Wanda asserted, “Since some of the community’s elected officials are opposing Sister Spirit, federal intervention is the only way to mediate the situation.”12

Bolstered by national attention and extensive national news coverage—Newsweek, The Village Voice, Oprah Winfrey, and Jerry Springer all featured the story, and headlines appeared across the country through the syndicated news services—pressure grew on the federal government to intervene. On February 21, 1994, Reno sent in federal civil rights mediators to resolve their “first gay-harassment case,” based on a January 9 mail threat against the Hensons. Wanda asked the New York Times, “If the K.K.K. was harassing blacks and Jews and trying to kick them off their land, do you think it would be allowed? People think it’s different. Well, it’s not.”13

Although the intervention by Attorney General Reno kept Camp Sister Spirit in the national headlines, practically, the visit by the civil rights mediators had little effect. Sexual orientation was not a protected category, and there were no federal tools to aid the Hensons and Camp Sister Spirit. Living on the land in Ovett, they had to protect and defend themselves and rely on local law enforcement to do their jobs.

Camp Sister Spirit was a cause célèbre for the lesbian and gay movement. For the first time in many people’s memories, gay and lesbian communities had positive attention from the White House. Presidential candidate Bill Clinton had addressed queer people directly for the first time during a presidential campaign in 1992 saying, “I have a vision and you’re part of it.” He pledged to end the military ban, support federal civil rights laws, and launch a “Manhattan-type” project to cure AIDS. The situation in Mississippi offered an opportunity for the administration to prove themselves.14

Women gathered at Camp Sister Spirit.

For local evangelicals like Allen, a Southern Baptist pastor from nearby Richton, the question was not about civil rights, but about the local community’s rights for self-determination. Speaking to the Baltimore Sun in March 1994, he conceded, “Homosexuals and lesbians are not unknown to our community. The lifestyle has never been condoned. But they have never been harassed. To a large measure, this is about a community. Can a community define itself?” Allen granted the limits to self-determination, noting, “This community cannot define itself as white or male or female. Or Baptist even. We acknowledge those necessary and right distinctions. But sexual preference is not a civil right.”15

The Hensons drew clear analogies between what was happening to them as lesbians and what had happened to African Americans and Jews in the United States. In partnership with the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF), the Hensons catapulted into national consciousness the idea that gay and lesbian people should be protected by civil rights laws and precipitated the first intervention by a US Attorney General on behalf of gay and lesbian people under federal civil rights laws.16

Hendry, Walley, and Allen mobilized around the idea that everyone in Ovett and broader Jones County was opposed to the Hensons, but many different perspectives existed. Letters to the Editor, quotations in news articles, and words from people on the street demonstrate both strong support for the Hensons, particularly from Black residents, and disinterested ambivalence. Geneva Walters, who had “just opened a thrift shop in the old gas station in Ovett,” told the Baltimore Sun that she didn’t condone the Hensons, but “you can’t run people out of town because you don’t like what they’re doing.” What should not be overlooked is the extraordinary humor that some people brought to the situation. One longtime Ovett resident joked to the Baltimore Sun, “If it would have been left alone, the mosquitoes, the bedbugs and the ticks would’ve moved them out by springtime.”17

Before Camp Sister Spirit

Brenda and Wanda Henson were active lesbian-feminists locally and regionally for years before founding Camp Sister Spirit. Together and separately, they built other feminist and lesbian communities in Mississippi and connected southern women with a national network of lesbian-feminist music festivals, such as the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival in Hart, Michigan, and the National Women’s Music Festival, held in Illinois and other midwestern locations. One of their projects was a feminist bookstore in Gulfport.

Southern Wild Sisters Unlimited opened in November 1987 at 250 Cowan Road. Brenda, then 42, wrote Feminist Bookstore News to explain how they raised the money needed to open and stock the store. “We sold our hand-crafted items at festivals all summer, known as ‘Dixie Dykes,’” she explained. “Other craftswimmin bartered with us or just made donations to help us get started. Sisters at the festivals were generous to the cause, and the bank finally OK’d a second mortgage. We do not have all we had hoped to have but we are on our way.” In addition to books—“the latest reference books on AIDS, incest, child abuse, adult children of alcoholics, aging, death and dying,” as described in Gulfport’s Sun Herald— the store also had “a lending library and plans for workshops, counseling services, guest speakers, a braille library, a coffee house and a bulletin board that lists social services and professional and blue collar workers, all female.” In addition, local groups and organizations used the space for meetings. Brenda was working on an undergraduate degree in criminal justice when the store opened. After graduation, she told the local paper, she hoped “to make enough noise through her bookstore to inspire women not to settle for the ‘leftovers that society gives us.’”18

Top: Woman reading at Camp Sister Spirit. The “No Guilt” tattoo is a design inspired by Diane DiMassa’s Hothead Paisan, Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist. Bottom: Women working at Camp Sister Spirit.

For nearly four years, Southern Wild Sisters Unlimited was a vibrant part of the Gulf Coast, attracting women from Southern Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama, and advertising in local and statewide gay and lesbian newspapers. As a community hub, the shop organized sober and chem-free salons and ran a food pantry and clothing exchange.

In March 1989, the Hensons organized the first annual Gulf Coast Women’s Festival held near Lumberton, Missisppi. Featured musicians included Sue Fink, Terese Edell, June Millington, and Tender, in addition to a talent show for local performers. Participants included southern activists Suzanne Pharr, an organizer from Little Rock, and Pam Martin, an organizer from Atlanta. Two hundred fifty people registered for the festival and, as the Hensons reported, that included “sisters from 12 other states, El Salvador, Jamaica, and Canada.” “Our community continues to grow. We do not feel as alone and isolated as we once did,” Brenda wrote in This Month in Mississippi. “We are beginning to speak with a loud, proud voice, in harmony and support of one another. We are past the ‘trying’ stages and we are now ‘doing.’”19

The second Gulf Coast Women’s Festival took place a year later and featured lesbian-feminist musician Alix Dobkin. Marise Boehs reported that the gathering focused on “regionalism, racism and politics” with a heavy dose of “songwriting and dance as well as gemstones, healing and lesbian magic.” Boehs also described Wanda Henson’s “tent revival style plea for money” and how “a pillowcase was passed through the crowd gathering cash, checks and pledges for money to buy land.”20

What is striking about the Hensons’ public missives before purchasing the land in Ovett is their spirit of experimentation. Raising funds to support the work was a part of their innovative approach; in February 1989, the Hensons announced a membership plan to the 1,000-plus subscribers of their mailing list as well as in community newsletters. “Wild sister” and “wild mister” memberships cost $5 and were available to everyone. The Hensons embraced any and all ideas that might be of service to their project to build communities for lesbians and feminists in Mississippi. Their work was significant. The Hensons demonstrated boldly and repeatedly that lesbian-feminists could live and organize openly in Mississippi.21

The Hensons announced in spring 1991 that they had turned Sister Spirit Incorporated into a nonprofit. The organization’s purpose was “to provide education, information, counseling referral and advocacy, and meeting space for persons and groups addressing social issues.” In addition, they had a Land Fund, Left-Overs (recycled clothing and household items), food, and an Oral Herstory project. And they continued to operate Southern Wild Sisters Unlimited. Brenda told folks the shop would close when the bookstore’s property sold. Reflecting on the bookstore’s success, Wanda wrote, “Since Southern Wild Sisters, Unlimited Bookstore opened four years ago, we have been INVOLVED with our community.” She enumerated the meeting spaces offered to multiple groups, the referrals that they received from local organizations, and the direct action they’d taken on behalf of gay and lesbian people, people with AIDS, and women. Success for the Hensons was “Standing up for what we believe in, sharing what we have, not compromising our values, being proud of who we are and getting respect in return, making ourselves and our abilities available to help others get started or to heal, and feeling good about our work everyday,” Wanda wrote, “just knowing we are making a difference in our lives and the lives of many people.”22

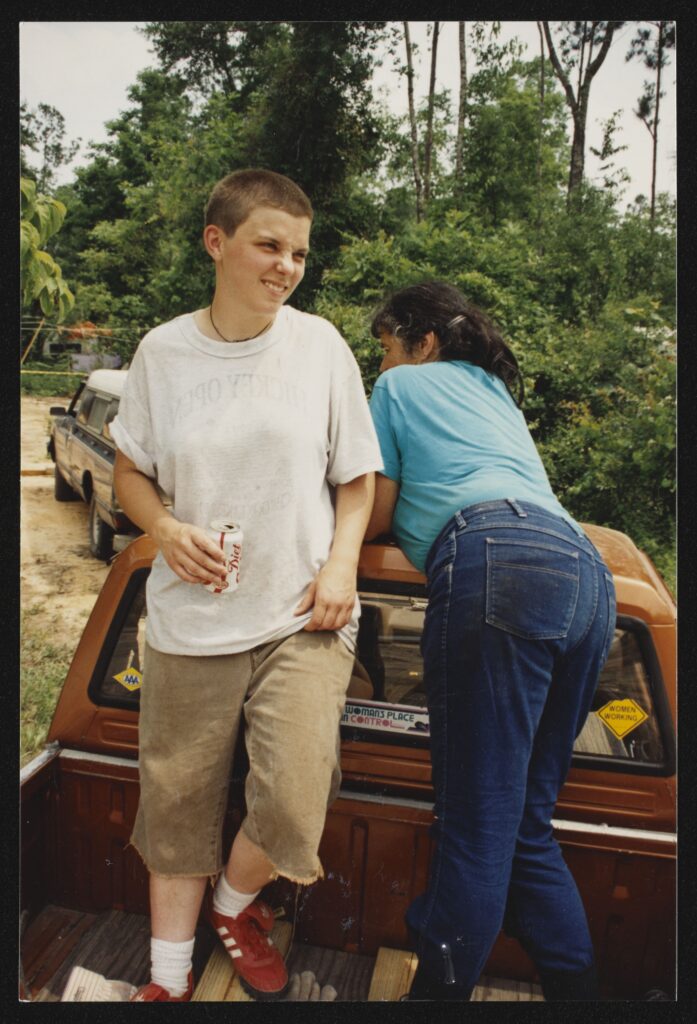

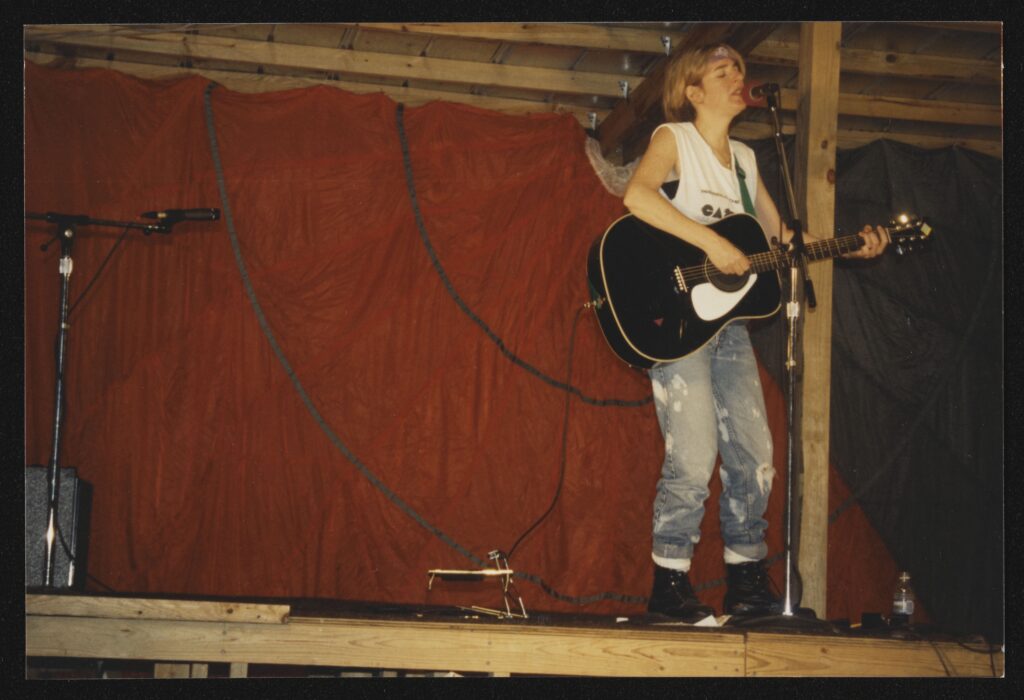

SONiA from disappear fear singing on stage at Camp Sister Spirit.

Ovett After the Attorney General-Ordered Visit

In April 1994, the Hensons held the Gulf Coast Women’s Festival, but many performers and attendees stayed away, concerned about safety. Fifty-three women participated in the festival and only one performer, Sonya Rutstein from Disappear Fear. Over the next six months, Camp Sister Spirit continued to make headlines as local residents organized against the community and the Hensons.23

Two lawsuits were filed against Camp Sister Spirit. In one, two Jones County residents, James Hendry and Reverend John Allen, sued Camp Sister Spirit and the US Civil Rights Division. That case was dismissed on May 19 by US District Judge Charles Pickering, who said that they could not sue the Attorney General but also that the Civil Rights Division has “no authority to come down here unless both parties invite them.” A second lawsuit was brought by eleven Jones County residents to prevent Camp Sister Spirit from building on their property.24

Lawsuits—whether initiating them or defending them—cost money. So, in April 1994, the Hensons traveled to San Francisco to raise funds to support Camp Sister Spirit. They received a warm reception from Bay Area activists, and raised $10,000 to “add more alarms, barbed wire fences, and an emergency generator.” They invited activists to Camp Sister Spirit to help with the work of clearing the land, building on it, and ensuring the safety of the residents. Not to be outdone, James Hendry and Mississippi for Family Values, who organized the opposition to the Hensons and Camp Sister Spirit, told the AP they had raised about $11,000.25

In March 1994, Representative Barney Frank, the first Representative to come out while in Congress, asked the House subcommittee on civil and constitutional rights to hold hearings in Mississippi “to determine if local officials are safeguarding the Hensons’ rights.” And in late June, local newspapers announced that those congressional hearings would be held in Jackson at the McCoy Federal building on Wednesday, July 6, 1994. Representatives Barney Frank and Jerrold Nadler came to Mississippi for the hearing. They investigated whether the Hensons were being harassed and built an evidentiary record for future Congressional consideration to include sexual orientation in hate crimes laws. The Frank-Nadler hearings happened in a single day, and Frank quipped on his way out of town that he was “leaving before sundown,” a reference to sundown towns in the US South, and a rhetorical move that aligned the Hensons’ struggles as lesbians with the historic and continuing struggles of African Americans for civil rights.26

By the end of the summer, just as the Camp Sister Spirit controversies seemed settled with the dismissal of lawsuits and other legal proceedings, two gay men were murdered in Jones County. National organizations called for an investigation of the murders of Joseph Shoemake, aged twenty-four, and Robert Clyde Walters, aged thirty-four, as a hate crime. A few days after those murders, Marvin McClendon, a sixteen-year-old tenth grader, was charged with the double homicide. But the Ovett County sheriff ruled that the incident was not a hate crime. McClendon would go on trial for murder, and in February of 1995, McClendon was convicted and sentenced to two life sentences. For gay and lesbian activists, the use of HIV status in the trial (one of the gay men was HIV positive) was an issue of concern, but the swift conviction blunted further discussion.

Through these events, the Hensons and other women at Camp Sister Spirit continued their work and activism. According to the Baltimore Sun, Wanda told one threatening caller, “We’re not leaving.” She recounted the caller’s reply, saying, “That’s yet to be seen. . . . I ain’t got nothing against you or whatever you want to do. This is not the place for you to do it.” But Ovett County was the place that the Hensons had chosen to build their lesbian community and festival. It was their place, as Wanda put it, and they would stay.

Continuing the Work

By the fall of 1994, the Hensons and Camp Sister Spirit were no longer in the headlines. The lawsuit filed by eleven Ovett County residents in March 1994 was dismissed in July 1995. Camp Sister Spirit could continue their work without threat of litigation. After the paltry turnout for the 1994 festival, the festival was back in full swing by the next year. And on their own land, women gathered in high spirits. They sang and danced finally expressing, at least during the festival weekend, their freedom. Camp Sister Spirit was a space for celebration and education. As Wanda put it, “everybody here learned about gay and lesbian rights that we do not have. And we also talked about the human rights that have been violated against Camp Sister Spirit—17 out of 30!” Building on the spirit to help others, the Hensons and the women of Camp Sister Spirit went to Mexico later that year delivering medical supplies and clothes.27

Over the next seven years, Wanda and Brenda held festivals, organized programs for women and lesbians, and operated a food bank, along with other service work that benefited the people of Ovett—and the surrounding Mississippi Gulf Coast. In March 1996, they organized a lecture and visit by Loretta Ross, the executive director of the National Center for Human Rights Education. When necessary, they also acted as open spokespeople on issues like Ellen DeGeneres’s coming out episode, gay marriage bans, and the inclusion of gay and lesbian people in the US Census. But the Hensons mostly became an ordinary part of the community. Brenda contributed op-eds to the Hattiesburg American, more often about service to community than about lesbian issues.

In 2005, Brenda and Wanda Henson left Camp Sister Spirit for Edgard, Louisiana, though they still owned the land. Brenda was diagnosed with cancer and Wanda needed new work to support her. When marriage between two women became legal in Massachusetts in May 2004, they were among the first to marry. In February 2008, Brenda Henson died from colon cancer at the age of 62, as Wanda held her in her arms.28

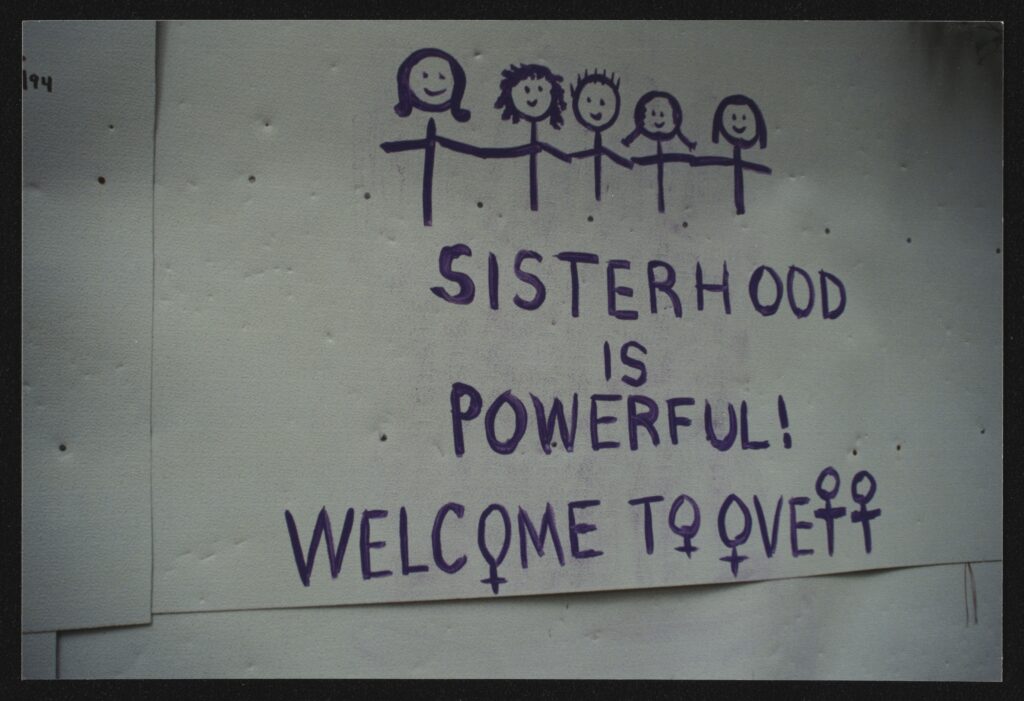

Hand-painted sign at Camp Sister Spirit.

Camp Sister Spirit’s Continuing Legacies

Camp Sister Spirit highlights the tenacity, perseverance, and persistence of southern lesbian activists. While the story may be distilled as an example of virulent homophobia in the US South, it is also a story of the commitment of southern lesbians to living their lives in the places they choose and building community around them. Camp Sister Spirit demonstrates two important ideas often overlooked in queer historiography: the numerous contributions of lesbian-feminist cultural activism from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, and the importance of the South—and the state of Mississippi—to achievements in the queer past.

Camp Sister Spirit arose from the dynamism of the womyn’s music movement in the US and from theories of lesbian separatism that circulated in the women’s liberation movement. The women’s music movement flourished beginning in the early 1970s and continuing through the 2000s. Lesbian separatism is the idea that separating from broader patriarchal, homophobic society and focusing on communal formations of only women could strengthen lesbians and women to discover non-oppressive life ways. Lesbian separatists adapted the idea from observations they made from Black Power movements, promulgating the theory that separatism could be enacted in women’s daily lives in a range of beneficial ways. Festival communities and womyn’s music were one vibrant expression of lesbian separatism, as were the many womyn’s land communities that were formed during the 1970s and 1980s. The Hensons practiced a form of lesbian separatism that served their time and place. The festivals they organized were for women only, but they lived on the land with their son and a range of people came to other events on the land. While cultural feminism and lesbian separatism as intellectual projects have been vilified in some scholarly and popular literature, the generative qualities of the ideas and formations are extraordinary. Acknowledging the cultural and separatist roots of Camp Sister Spirit highlights the value of those ideas, not only for women and lesbians living in spaces perceived as “progressive” or “liberated” but also in conservative places like Mississippi.29

While Camp Sister Spirit served a national agenda for gay and lesbian activists during the 1990s on the questions of civil rights, over the course of its lifetime, Camp Sister Spirit embodied multiple visions for queer communities. Wanda and Brenda offered their partnership as a vision for what marriage between two women would look like. That vision came into reality in 2004, but it was not recognized throughout the country until 2015. The Hensons and Camp Sister Spirit also offered the idea that lesbian communities—and lesbian separatist communities—could be an integral part of all communities around the United States. Lesbians and feminists could contribute meaningfully to civic life in any type of community, no matter what ideas people had about queer people. Camp Sister Spirit also embodied the ideas of giving back through mutual aid and that when lesbians, gay men, bisexual, and transgender people are included in communities as openly queer, they can be known, accepted, and valued. They also can be a resource for the community in times of suffering and stress, as Camp Sister Spirit was in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The Hensons and Camp Sister Spirit modeled, inspired by the cultural activism of lesbian feminism, the ways that queer people could be openly a part of communities and make contributions as informed citizens. Their vision of a future where lesbians can be out and accepted anywhere, including the rural South, has in many ways been realized.

While the loss of lesbian spaces is contested in lesbian studies, there is a different valence for the loss of lesbian spaces in rural communities. In urban settings, queer communities change and morph over time—and the losses of spaces, projects, and initiatives are generally replaced with relative efficiency by other formations. In rural communities, however, the loss of a space, whether an organization like Camp Sister Spirit, a local gay bar, or a social organization, is not often replaced quickly or easily, or at all. The vision, energy, and resources to put together a community project often comes from a small number of people and when the project ends the community may remain fallow for a spell waiting for additional people and resources to mobilize. Preserving queer spaces and initiatives in rural communities, particularly rural southern communities, demands additional urgency, attention, and resources.

Camp Sister Spirit is still owned by Wanda Henson, but the organization is no longer active. The houses on the property and the bunk house are still intact, though all the structures need repair. For more than fifteen years, Camp Sister Spirit was a home to Wanda and Brenda Henson and an array of visitors and land caretakers. In spite of opposition, women came from around the South and across the United States to live in community and build structures both physical and metaphorical to support the dreams and visions of lesbians and queer people. If you listen, you can still hear the music of lesbian liberation playing in Mississippi. As we dream, new spaces for gathering and celebration emerge.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Wanda Henson, November 21, 1954–May 22, 2025.

Julie R. Enszer, PhD, is a scholar, editor, and poet. Her scholarly book manuscript, A Fine Bind, is a history of lesbian-feminist presses from 1969 until 2009. Her scholarly work has appeared or is forthcoming in Journal of Lesbian Studies, American Periodicals, WSQ, Post45, Frontiers, and other journals. She is the author of five poetry collections, most recently The Pinko Commie Dyke, with illustrations by Isabel Paul (Indolent Books, 2024).

Enszer is editor a number of award-winning collections including Fire-Rimmed Eden: Selected Poems by Lynn Lonidier (Sinister Wisdom 2023) and OutWrite: The Speeches that Shaped LGBTQ Literary Culture with Elena Gross (Rutgers University Press, 2022) which won a 2023 Lambda Literary Award for LGBTQ+ Anthology. She edits and publishes Sinister Wisdom, a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal and is an Instructional Assistant Professor with the Sarah Isom Center at the University of Mississippi. You can read more of her work at www.JulieREnszer.com.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to students at the University of Mississippi who remind me each semester how urgent this queer, feminist history is to their contemporary lives. Special gratitude to Jonathan Schrock who worked with me for two semesters researching this history; this article benefits from his keen eye and passion for the story. Robin Morgan graciously arranged a tour of Camp Sister Spirit for Jonathan and me one hot August day; her stories energized us both and helped guide this article. Thank you to Hooper Schultz and Jaime Harker for the call for papers on “The Queer South” and to the generous and helpful editors at Southern Cultures.

NOTES

- “Dear Sisters (Letter from Brenda Henson),” Feminist Bookstore News 16, no. 4 (November 1993): 5; “Dear Sisters,” 5; Sharon Stallworth, “‘Oprah’ eyes debated retreat,” The Clarion Ledger, December 13, 1993, 1. It was a common practice among feminist and lesbian activists at the time to change their names and adopt a matrilineal name.

- “Dear Sisters,” 5; “Dear Sisters,” 5.

- Bill Turque, “Mississippi Burning,” Newsweek 122, no. 25, December 20, 1993, 33.

- J. D. Hendry, “Ovett resident says, ‘No Thanks, to lesbian retreat,” Hattiesburg American, November 28, 1993, 13A; Hendry, “Ovett resident says, ‘No Thanks.’”

- Hendry, “Ovett resident says, ‘No Thanks.’”; Peter Applebom, “Lesbians Say Mississippi Clash is Civil-Right Fight but Townspeople say values are at Heart of Dispute,” New York Times News Service in St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 22, 1994, 5C.

- Kate Greene, “Fear and Loathing in Mississippi: The Attack on Camp Sister Spirit,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 7, no. 2 (2003): 85–106; Kate Greene and Edward M. Wheat, “Camp Sister Spirit vs. Ovett: Culture Wars in Mississippi.” Southeastern Political Review 23, no 2 (1995): 321.

- Turque, 33; Janet Braswell, “Ovett residents vow to fight planned Sister Spirit retreat,” Hattiesburg American, December 7, 1993, 1; Turque, 33.

- “Sister Spirit: How has group harmed Ovett?” Hattiesburg American, December 8, 1993, 13A.

- Green and Wheat, 318.

- Stallworth, “‘Oprah’ eyes debated retreat,” 9A; Eloria Newell James, “Sister Spirit foes take case before county officials,” Hattiesburg American, December 21, 1993, 1.

- Sharon Stallworth, “Opponents of Ovett feminist-retreat center plan to file suit,” Jackson Clarion-Ledger, Tuesday, January 4, 1994, B1.

- Braswell, 1.

- Peter Applebom, “Mediators Taking Role in Dispute on Lesbians,” New York Times, February 21, 1994, A10.

- Of course, feminists, including lesbians, had attention from the Oval office during the Carter administration as documented by Doreen J. Mattingly in A Feminist in the White House: Midge Costanza, the Carter Years, and America’s Culture Wars (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016) and Marjorie J. Spruill’s Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017); Michael Isikoff, “Gays Mobilizing for Clinton as Rights Become an Issue,” Washington Post, September 28, 1992.

- Ann LoLordo, “Lesbian vision clashes with small town’s culture,” Baltimore Sun, March 23, 1994, 1A.

- Christina Hanhardt documents the growing gay and lesbian movement to include sexual orientation in hate crimes legislation in “Visibility and Victimization,” Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and the Politics of Violence (Duke University Press, 2013), 155–184. Hanhardt’s analysis of how “the anti violence movement” produced “a shared investment in the goals of gay safety, achieved through anticrime strategies, and visibility” is resonant with the Hensons’s appeals through the NGLTF, and this story also complicates her analysis given the southern, rural nature of the conflict.

- LoLordo, 1A.

- Letter from Brenda Henson, Feminist Bookstore News 10, no. 4 (December 1987): 6–7. Craftswimmin is an alternate spelling for women that some lesbian-feminists embraced in the 1970s and 1980s; Letter from Brenda Henson, Feminist Bookstore News 10.

- Marise J. Boehs, “1st Annual Gulf Coast Women’s Festival,” This Month in Mississippi (April 1989), 7–8; Brenda Henson, “Hello Mississippi! Gulfcoast News . . .,” This Month in Mississippi 16, no. 6 (June 1989), 5.

- Marise Boehs, “2nd Annual Gulf Coast Women’s Festival, This Month in Mississippi 17, no. 5 (April & May 1990), 4.

- Brenda and Wanda Henson, “Southern Wild Sisters Unlimited Books and Then Some,” This Month in Mississippi 16, no. 2 (February 1989), 9.

- Brenda Henson, “Letter to the Editor May 21, 1991,” This Month in Mississippi, 18, no .2 (March–June 1991), 4, 6.

- Bonnie Morris, Eden Built by Eves: The Culture of Women’s Music Festivals (Los Angeles: Alyson Books, 2000), 246.

- Emily Wagster, “Mediation ruled out in Ovett,” Clarion-Ledger, May 20, 1994, B1.

- “Feminist camp backers, opponents raise money,” Associated Press, April 14, 1994.

- “2 in Congress Hear Firsthand of Town’s Clash with Lesbians,” New York Times, July 7, 1994, B, 8.

- Morris, 248.

- Andy Humm, “Camp Sister Spirit’s Brenda Henson Dies,” Gay City News.

- For more information on the movement, see the work of Bonnie Morris, Ginny Benson, and the recent website curated by Holly Near, becauseofasong.com; see for example, Julie R. Enszer, “‘How to Stop Choking To Death’: Rethinking Lesbian Separatism as a Vibrant Political Theory and Feminist Practice,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 20, no. 2 (2016): 180–196, and Michael J. Lee & R. Jarrod Atchison, “’Dykes First’: Lesbian Separatism in America,” in We are Not One People: Secession and Separatism in American Politics Since 1776 (Oxford University Press, 2022).