“We ride the waves of supply and demand on the banks of the Mississippi, furs and cypress, cotton and cane, oil and gas, corn and grain, coal and aluminum, commodities bought and sold, always en route, pushed up and down river.”

They call it “Cancer Alley” because it’s got a reputation. The hundred-mile stretch between Bvlbancha (New Orleans) and Istrouma (Baton Rouge) was named in the 1980s, but today a more accurate accounting would expand it to include the roughly 255 miles from Baton Rouge to the Gulf of Mexico. The long colonial experiment began on the banks of the lower Mississippi River centuries ago with the clear-cutting of ancient bottomland hardwood forests and cypress swamps, making way for indigo and sugarcane plantations. Petrochemical plants have since replaced them, surrounded by deteriorating wetlands and communities plagued by and dependent upon the boom-and-bust cycles of petro-economics for employment and restoration efforts.

Cancer Alley, also known as “Death Alley,” is where the Port of South Louisiana reigns as the largest tonnage port in the Western Hemisphere, the United States’ second most active Foreign Trade Zone and its largest energy and grain transfer port. But supply and demand comes with a cost. Refineries and waste pits and toxic byproducts, seen and unseen, pockmark the landscape. Along the banks of the Mississippi River, a neglected part of the United States is bearing the brunt of the shale boom as a wildfire of new construction and the expansion of single-use plastic facilities and export terminals assault an environment with long-term investments, facilitating a pattern of violence against communities for the sake of carbon profits.1

This series of Cancer Alley collages layers evidence found in the public record with what I have witnessed as a photographer, reconstructing a history of the lower Mississippi River through the manipulation of US Geological Survey maps. The collages illuminate how these sites are variously represented or simply erased, and how the challenges of today are founded in colonialism, with rapacious multinational corporations and international financing fueling violations against basic human rights like clean water.

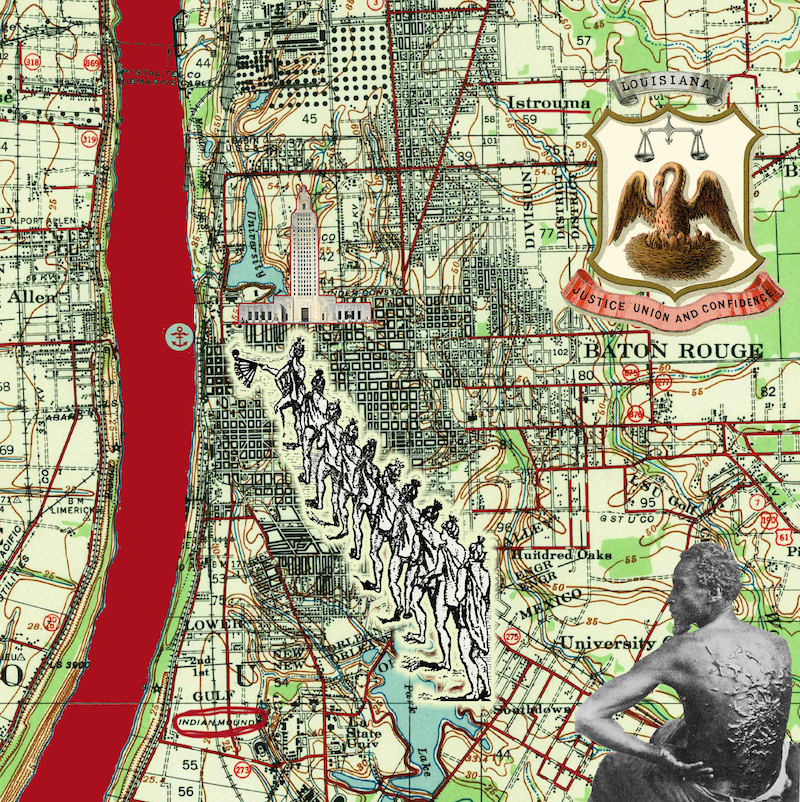

ISTROUMA: BATON ROUGE

Istrouma is both a place and a symbol, a red stick, le bâton rouge, used to mark territorial lines, acknowledging the Houma nation’s hunting grounds to the north and the rights of the Bayou-goula tribe to the south, or thus it was recorded in the journals of colonizers. Earthen mounds, built by Indigenous peoples between six thousand and 11,300 years ago, hold their sacred ground near the entrance of Louisiana State University’s Tiger Stadium, known as “Death Valley” and one of the largest college football stadiums in the country. Less than four miles away, in the shadows of Baton Rouge’s art deco capitol, Exxon-Mobil’s refinery sprawls as far as the eye can see.2

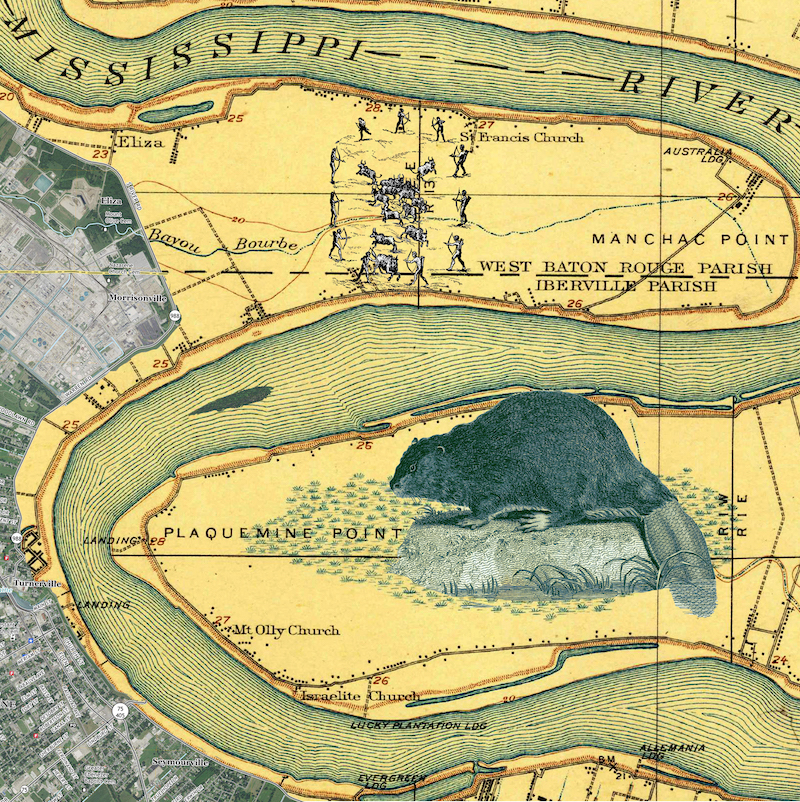

PLAQUEMINE ISLAND

The legacy of extraction has always been tied to the ability to move product to market, making the river the most valuable collaborator of enterprise. In the early years of colonialism, from the late seventeenth century through the 1920s, the fur trade fueled such a get-rich-quick furor that beavers, minks, muskrats, and other furry creatures nearly went extinct. Our modern era has no need for fur anymore, however the quest for comfort remains and is now inextricably tied to petrochemical products brought to us by multinational corporations.

Plaquemine is one of three Mississippi River islands, including Bayougoula and Bonnet Carré, all found between Istrouma and Bvlbancha. Bvlbancha (“place of many languages” in Choctaw) is the original name of the lower Mississippi River that was successfully rebranded “Nouvelle Orleans” by French colonizers. Plaquemine means persimmon in Mobilian, a pantribal pidgin language and the predominant trade jargon spoken in the territory when the colonizers arrived. Downstream from Baton Rouge, the river turns sharply at Manchac Point, beginning a series of tight twists as it curves south to find its mouth and the Gulf of Mexico. Archeologists believe the two mounds and causeway found on this point near Bayou Bourbeaux were inhabited by Indigenous people of the Plaquemine culture between 1300 and 1600. This sacred site was a strategic place of convergence, connecting communities to the watershed and its resources.3

Commercial industries disrespected and disconnected Native settlements and ceremonial grounds, corrupting historical and cultural ties to ancestral lands. In 1957, Dow Chemical purchased former plantation land along the west bank of the river, just south of Manchac Point, across the main channel from Plaquemine Island. It has since grown to become one of the largest petrochemical facilities in Louisiana. Over time, families were forced to leave Manchac Point, first for the Army Corps of Engineers levee infrastructure after the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, and later, in the late 1990s, for Dow Chemical to create a natural buffer or “green zone” around its facility. Dow’s Plaquemine plant produces chlorine and polyethylene, which are found in “cosmetics, detergents, solvents, pharmaceuticals, adhesives, plastics for a variety of packaging, automotive parts, electronics components, and more.” Dow Chemical’s Louisiana Operations site is just one of more than two hundred chemical plants located between Istrouma and Bvlbancha.4

DONALDSONVILLE: POINT HOUMAS

The historic distributary La Fourche des Chitimatchas (the fork of the Chitimatcha), also called the River of the Chitimatcha, is known today as Bayou Lafourche. It has been disconnected from the Mississippi River by the federal levee system and mechanically reconnected by pumps in order to allow freshwater to nourish wetlands at the southern end, while also providing over three hundred thousand people in coastal communities with potable water. “The Fork,” or Lafourche, provided many First Nations, including the Chitimatcha and Houma, a gateway to the Yakni Chitto, the “big country,” where a web of bayous connects scattered Indigenous settlements to a sense of sovereignty—a place where people fleeing enslavement and, in later years, removals to western territories, found food security as American planters moved in to claim the high grounds to grow sugarcane after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.5

Bayou Lafourche has been and remains a life force for the Houma Nation, although it is crisscrossed by pipelines and pulls its water supply from a polluted source due to upstream runoff and industrial outfalls along the Mississippi. Its headwaters connect to the river at Donaldsonville in the heart of St. James Parish, a community saturated by the petrochemical industry. Just downriver from Donaldsonville, Formosa Plastics is planning to build a $9.4 billion chemical manufacturing facility along a 2,400-acre site they’ve dubbed “the Sunshine Project.” The operation threatens to double toxic air levels in the community to produce “nurdles,” plastic pellets used for single-use consumption. Formosa may be the largest, but even more plants are under construction or expansion along those riverbanks. St. James Parish is also where the tail of the Dakota Access Pipeline ends, linking up to the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, which runs 163 miles through the Atchafalaya Basin—North America’s largest river swamp— transporting Bakken crude across the United States, destined for international export.6

ST. JAMES: CANE AND CANCER ALLEY

Jacques Santiago Cantrelle, the namesake of Louisiana’s St. James Parish, came into the territory from Picardy, France, in 1720. He worked for the Company of the West Indies, operated by John Law, a Scotsman responsible for the radical public French finance reconstruction that contributed to the Mississippi Bubble. After the Spanish took control of the colony, Cantrelle was granted land between Bvlbancha and Istrouma at a place called Cabanocey, meaning “duck’s roost.” Cantrelle became commandant of that part of the territory, as did his sons-in-law and his son Michel, who was appointed first judge of St. James by Governor William C. C. Claiborne after the Americans “purchased” Louisiana. The Cantrelles first grew indigo, then sugarcane, on the fertile banks of the Mississippi, and colonial archives provide a unique record of their relationships with Houma ancestors, including my own, who lived along the back swamps of the Cantrelle family’s plantations. I have only recently learned that Cantrelle is my sixth great-grandfather on my mother’s side, illuminating the complexities of Indigenous histories and settler occupation, and the assimilation and cultural transformation brought on by these collisions, as reflected in my existence.

Near Cabanocey, the federal government has invested in an old salt dome site to bank petroleum as part of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve initiative. The old plantation grounds are now fallow, some cattle graze fields, but the land is covered by white oil tanks and access roads with names like the Department of Energy Road across from the old St. James Cemetery.

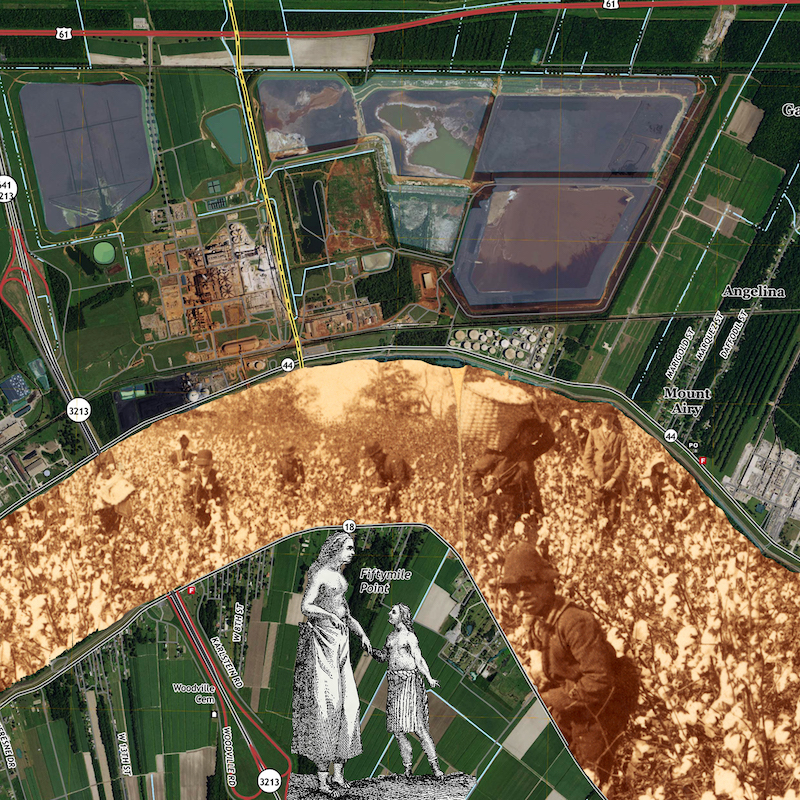

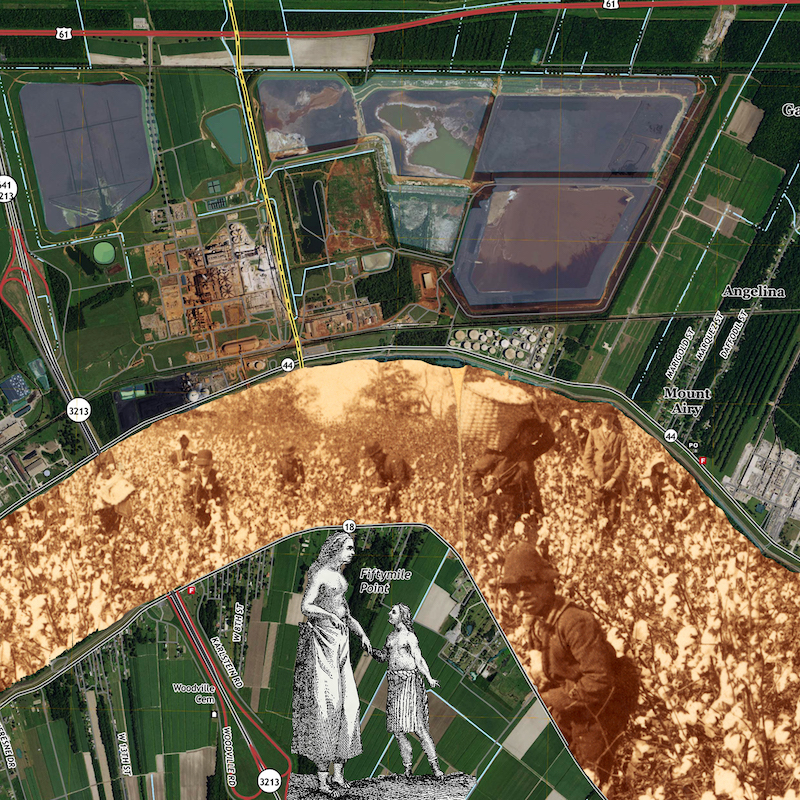

GRAMERCY: RED AND WHITE, COTTON AND BAUXITE

The extraction of land, labor, and lives has been the primary playbook for the colonial experiment. We ride the waves of supply and demand on the banks of the Mississippi, furs and cypress, cotton and cane, oil and gas, corn and grain, coal and aluminum, commodities bought and sold, always en route, pushed up- and downriver. Noranda Alumina glows as a red beacon in Gramercy, Louisiana, where bauxite ore from Jamaica is processed to extract alumina for producing aluminum metal and other products. The refinery almost went bankrupt a few years ago, and even though it is known to be Louisiana’s biggest polluter of mercury emissions, it recently was gifted a $1 million forgivable loan from Louisiana Economic Development Corporation to create a new residual pond for production waste.

COLLAGE INCLUDES: USGS map from 2018 Lutcher; J. F. Jarvis, Away Down ’Among de Cotton and de Coons, Louisiana, U.S.A., 1892, photographic print, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; Du Pratz, Indian Woman and Daughter, illustration in History of Louisiana, 37.BONNET CARRÉ CEMETERY

COLLAGE INCLUDES: USGS map from 2018 Lutcher; J. F. Jarvis, Away Down ’Among de Cotton and de Coons, Louisiana, U.S.A., 1892, photographic print, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; Du Pratz, Indian Woman and Daughter, illustration in History of Louisiana, 37.BONNET CARRÉ CEMETERY

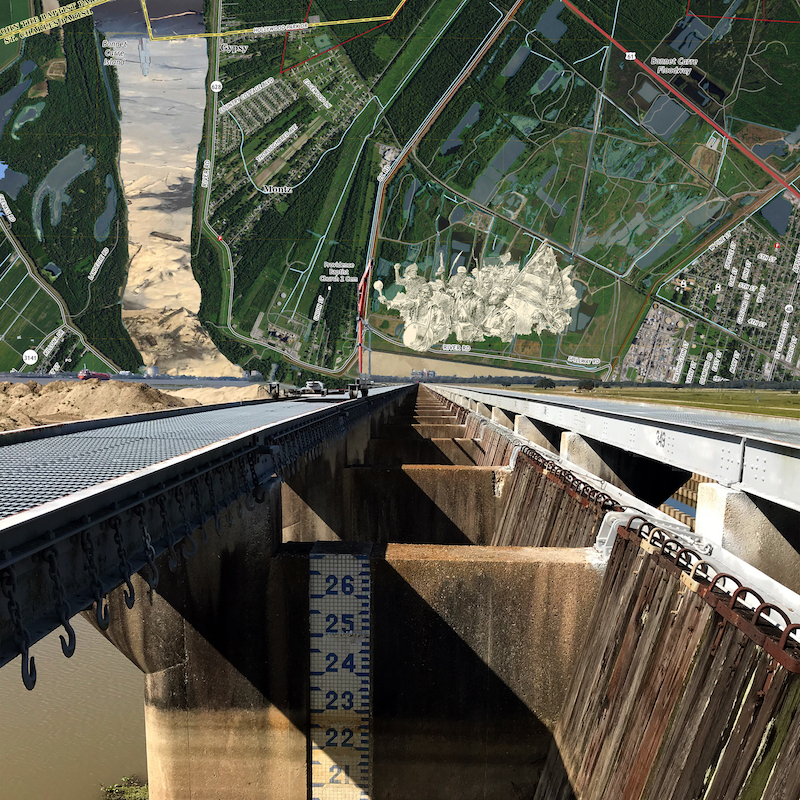

BONNET CARRÉ CEMETERY

There are two unmarked cemeteries in the Bonnet Carré Spillway just north of a census-designated place that is more refinery than town: Norco (derived from New Orleans Refining Company) in Louisiana’s St. Charles Parish. The historic 1811 slave revolt passed by the Bonnet Carré’s forgotten Roseland (Kenner) and L’Hermitage (Kugler) plantations as freedom seekers marched south toward Bvlbancha. Three hundred or more African Americans are buried in Roseland and L’Hermitage cemeteries. Many were enslaved at nearby plantations, but the cemeteries were also used as a final resting place for the bodies of their descendants and others tied to the plantations until 1928, just before the flood protection infrastructure was created after the Great Flood of 1927. Norco is celebrating ninety years as Shell Oil’s company town, proudly highlighting its corporate contributions from jet fuel to jazz and heritage festivals. Shell’s Norco Manufacturing Complex website boasts that the Norco facility is recognized as “one of the largest and foremost petrochemical facilities in the United States.” The refinery’s neighboring Army Corps of Engineers spillway, which had only been opened fourteen times in eighty years, was opened twice in 2019 and once in spring 2020 due to unprecedented high river levels, the side effect of a changing climate.

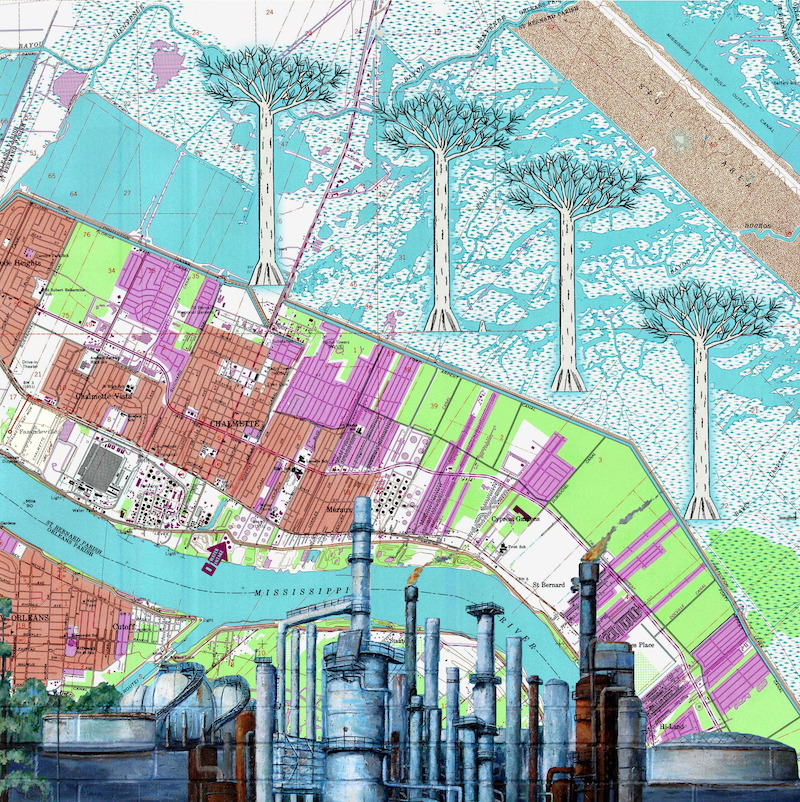

BVLBANCHA

The Choctaw called the high ground one hundred river miles from the Gulf of Mexico Bvlbancha (a place of many tongues or languages) because it had been a site of trade for years before colonizers sailed into the territory. The Ishak called it Nun Ush (the big village). The sinking Crescent City is sandwiched between petrochemical facilities up- and downriver, and known more for Bourbon Street and plastic Mardi Gras beads than as the vulnerable Isle de Orleans, with a history of immigration, slavery, and white supremacy linked to the commodification of natural resources and international trade. At one time, one third of United States cotton passed through Bvlbancha. At present, crude oil, natural gas, coal, steel, soybeans, maize, chemical fertilizers, animal feed, wheat, and sugar are a few of the major products traded along the river.7

BATTLE OF NEW ORLEANS

During the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson led a ragtag army of soldiers, black and white Creoles, enslaved men, Indigenous peoples, Kentucky militiamen, and others, with logistical support and supplies provided by the pirate Jean Lafitte, against the British in the Battle of New Orleans. After the Civil War, freedpeople founded Fazendeville, which became home to generations of African Americans until the National Park Service dismantled “the Village” in the 1960s to make way for the tourist attraction that New Orleans is today. The Chalmette Battlefield, which saw action during the War of 1812, is sandwiched between one of the largest sugar refineries in the Western Hemisphere and a petrochemical refinery, where a sweet-and-sour mix provides the community with few jobs and some of the worst air quality in the nation.

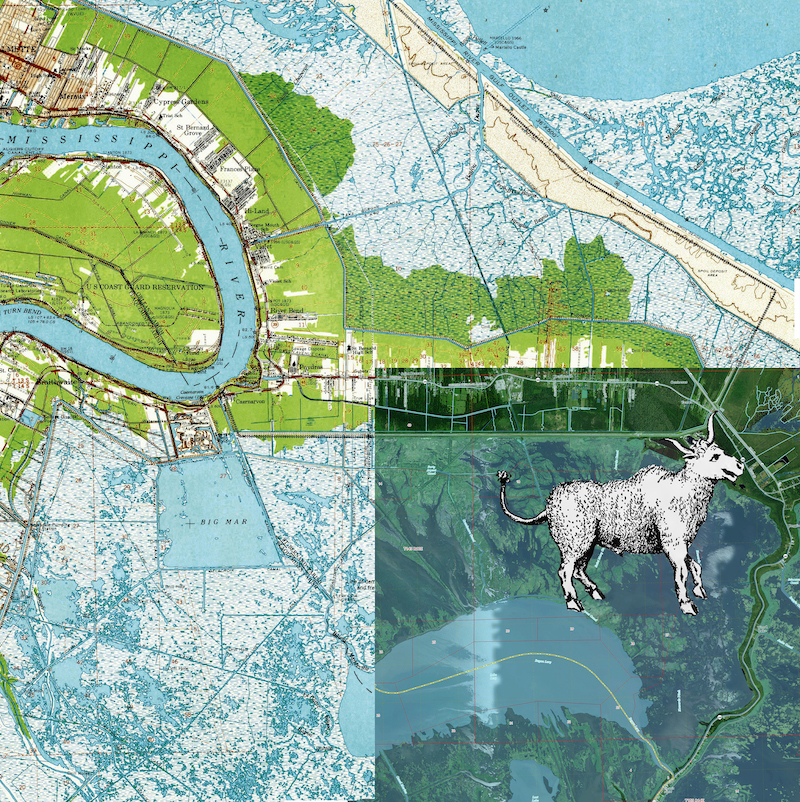

BAYOU TERRE AUX BOEUFS

South Louisiana is losing land at one of the fastest rates on the planet. The Bayou Terre aux Boeufs was once a distributary of the Mississippi, helping to build the St. Bernard lobe of the Delta as a channel providing freshwater and sediment to the wetlands. When colonizers came into the territory, they renamed the waterway after the bison (boeuf sauvage) found roaming the bayou banks and trembling prairies. Shortly after their arrival, the bison disappeared and levees were erected to control the river, cutting off the river’s natural tributaries, like the Bayou Terre aux Boeufs, and starving estuaries of the Mississippi’s life force. Coastal master planners will attempt to engineer restoration by reconnecting the river to the wetlands with new sediment diversion technology, but fishers fear what river waters saturated by nitrogen (responsible for coastal dead zones) and other upstream toxins will do to an already fragile ecosystem seeking a balance of fresh- and saltwaters as sea levels rise.

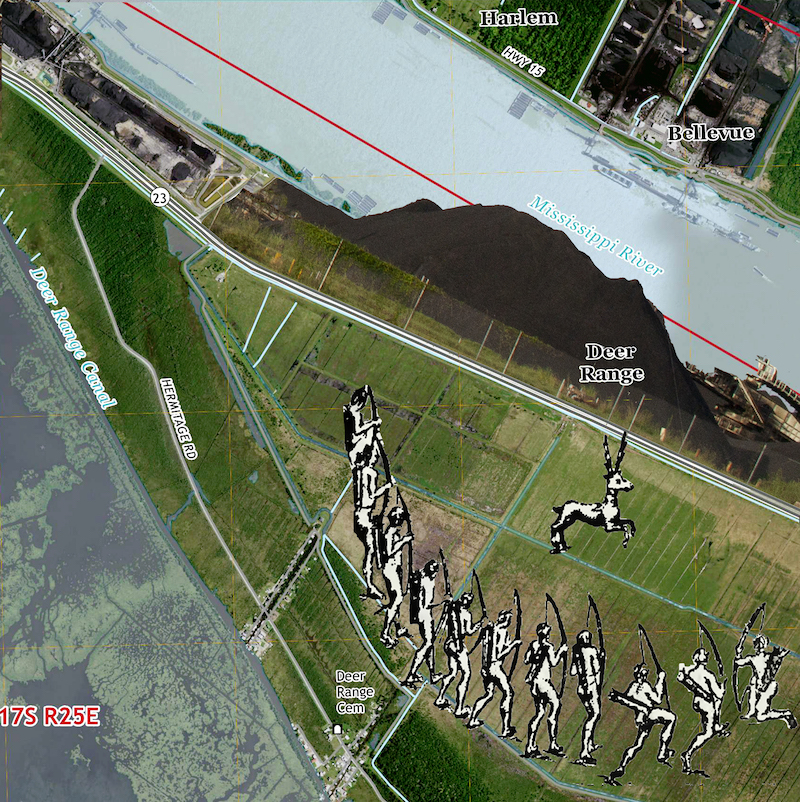

PLAQUEMINES: HARLEM AND COAL

Outside federal “risk reduction” infrastructure, Plaquemines Parish hugs both banks at the end of the Mississippi River. These narrow strips of dry land, surrounded by water and wetlands, are where major oil refinery and coal terminals occupy the highest ground near the mouth of the river—with more facilities and pipelines and major environmental restoration efforts on the horizon. Although the state doesn’t mine a tremendous amount of coal, South Louisiana is the nation’s third-largest coal exporting port.8

This essay appears in the Art & Vision Issue (vol. 26, no. 2: Summer 2020).

Monique Michelle Verdin is an interdisciplinary storyteller who documents the complex relationship between environment, culture, and climate in Southeast Louisiana. She is cowriter and producer of the documentary My Louisiana Love and her work is featured in a variety of environmentally inspired projects, including the multiplatform performance piece Cry You One, the essay collection Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas, and the collaborative book project Return to Yakni Chitto: Houma Migrations. She is director of the Land Memory Bank & Seed Exchange and a member of Another Gulf Is Possible Collaborative, working to envision just economies, vibrant communities, and sustainable ecologies.NOTES

- “Facts at a Glance,” Port of South Louisiana, accessed April 3, 2020, http://portsl.com/facts-at-a-glance/.

- Youssef Rddad, “LSU Mounds Could Be Oldest Man-Made Structure, but Peer Review Necessary, Professor Says,” Advocate, January 19, 2020, https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/article_2256d93e-330a-11ea-b696-5785641b6610.html

- “Plaquemine-Mississippian,” Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism, accessed May 10, 2020, https://www.crt.state.la.us/dataprojects/archaeology/virtualbooks/LAPREHIS/plaqu.htm.

- Lylla Younes, Al Shaw, and Claire Perlman, “In a Notoriously Polluted Area of the Country, Massive New Chemical Plants Are Still Moving In,” ProPublica, October 30, 2019, https://projects.propublica.org/louisiana-toxic-air/; Antonia Juhasz, “Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley’ Is Getting Even More Toxic—But Residents Are Fighting Back,” Rolling Stone, October 30, 2019, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/louisiana-cancer-alley-getting-more-toxic-905534/.

- Bayou Lafourche Fresh Water District, accessed April 4, 2020, http://www.blfwd.org/.

- Lylla Younes, “What Could Happen If a $9.4 Billion Chemical Plant Comes to ‘Cancer Alley,’” ProPublica, November 18, 2019, https://www.propublica.org/article/what-could-happen-if-a-9.4-billion-chemical-plant-comes-to-cancer-alley.

- “The 1884 Cotton Expo and New Orleans’ First Case of World’s Fair Fever,” NOLA.com, May 17, 2017, https://www.nola.com/300/article_21fc06f9-a1f5-56f8-8440-dee682805dfe.html.

- “Profile Analysis,” Louisiana State Profile and Energy Estimates, US Energy Information Administration, updated March 19, 2020, https://www.eia.gov/state/analysis.php?sid=LA.