“Slavery is everywhere the pet monster of the American people.” —Frederic Douglass

“Comfort has come to be its own corruption.” —Lorraine Hansberry“

We should not presume a desire for freedom.” —Jared Sexton

In her 1943 essay for The American Mercury, “The ‘Pet Negro’ System,” writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston transforms the literary genre of the journal article, discomfiting its traditionally genteel form with the exuberant and colorful rhetorical punches of the Black political pulpit. Staging a community callout embedded in southern specificity in a northern publication, Hurston adopts the oratorical approaches that emerge in the early Black churches of the South to address the moral and political problem of comfort, “an aspect of the race problem ignored by zealous reformers” (1), as it concerns race relations in the US South, as well as geographies beyond its reach. To do so, she takes on the role of the preacher who is, in her assessment, the “first artist” of Black American cultural life and a touchstone in a tradition of Black language and performance that originates and innovates itself most notably in the southern United States. Translating a Black sermonic tradition into a textual form, Hurston writes with the command of the preacher and the authority of the critic-essayist in order to name the unspoken ideologies that undergird the American South and its corresponding social scripts of Jim Crow segregation. Hurston theorizes southern interracial relations by housing them within the language and structure of the “Pet Negro system”—a network of allegiances, allowances, and betrayals that shape the lives of Black and white southerners. As she expertly notes, this southern system of racial domination and divine entitlement hinges on the possibility of the Pet Negro.1

Opening with a pastor’s charm, Hurston commands the attention of her readership-ministry in the first two lines: “Brothers and Sisters, I take my text this morning from the Book of Dixie. I take my text and I take my time” (1). Hurston turns toward what she calls the Book of Dixie—The Word of southern racial decorum drafted under slavery—as the foundation for her sermon. This informal though auspicious text is grounded by a fundamental doctrine: “no man shall seek to deprive a man of his Pet Negro” (9). The promises of the Book of Dixie read as follows: “every white man shall be allowed to pet himself a Negro” (1). Recounting a social order of race relations, Hurston declares that the South operates according to a racial doctrine that caters to white southerners’ desires for a more elastic and solemn mode of domination—the right “to pet and to cherish.” An inversion of the Book of Common Prayer’s matrimonial ordinance to “love and to cherish, till death do [they] part,” Hurston’s Book of Dixie pronounces an extramarital union, no less concerned with the politics of comfort and care, that belies its true investment in securing the bondage of its beloved (1).2

Per Hurston’s definition, “the Pet Negro, beloved, is someone whom a particular white person or persons wants to have and to do all the things forbidden to other Negroes” (3). Opening up a crucial discourse on access, allowances, community, exceptionalism, and notions of betrayal, Hurston’s definition frames “cosy Negroes” as figures of a domestic economy of care. In her estimation, these “pets” are victims and conditional beneficiaries of an intricate system that regulates and manages Black comfort by optimizing neglect. In thinking of those “chosen ones” who’ve been granted access to the exclusive white world and its offerings—namely, educational opportunities, social mobility, and financial means—Hurston resists the temptations of denying Black desire for complicity. She is not interested in claims to innocence because purity, too, is a logic of power. Thus, rather than describe the Pet Negro as an unknowing participant in this system of allowances, Hurston exposes the irony of the predatory co-dependencies at the core of this system. For, it is precisely this shameless organization of care, neglect, and violence that, she argues, “a lot of black folk, I’m afraid, find mighty cosy” (3).

Hurston’s use of the words “cosy” and “afraid” linger as the essay’s most subtle yet trenchant critiques. While giving voice to the systemic structures that shape Black-white relations in the post-Emancipation and post-Reconstruction South, Hurston is careful in her consideration of the morally and politically complicated ways Black people negotiate their own well-being within hostile territory. Hurston asks that we contemplate what it means to be comfortable and cautions us against its seductions. She asserts that no one who relishes the fruits of inequality—luxuries that are “forbidden to other Negroes” (3)—should go unchecked for their indulgence. In taking seriously the political implications of coziness, “The ‘Pet Negro’ System” serves as a critical intervention in the politics of comfort, which, here, concerns an exceptional racialized positionality. If one knows relative comfort within an anti-Black structure predicated on maximizing Black discomfort via precarity, brutality, and neglect, then what is the cost of attaining that individual comfort? How can one rejoice knowing the distress they have been spared continues to be meted out upon others? How can one be both colored and cozy?

In 1943, Hurston set out to critically account for the role that narratives of Black comfort have played in the perpetuation of Black suffering. Fourteen years before E. Franklin Frazier’s Black Bourgeoisie would assert that “when the opportunity has been present, the black bourgeoisie has exploited the Negro masses as ruthlessly as have white,” Hurston had “cosy Negroes” in her sights as an elite class of the abject made possible by a host of economic, social, and political displays of white affection toward select Black people. Knowing well that “these comfortable, contented Negroes are as real as the sharecroppers” (6), Hurston does not pull punches in her analysis of the Pet Negro. As she attests, despite their increased access to educational and social resources which are widely inaccessible to the Black masses, the Pet Negro remains just as psychologically concerned with strategy, status, and survival as the sharecropper. Southern Black folks of the twentieth century understood that the stakes of white affection and affinity are a matter of life and death. Hurston herself notes the calculus of security that shapes the Pet Negro’s thinking about the allegiances they embrace. “It would be a hard-up Negro who would work for a [white] man who couldn’t get his black friends out of jail” (5), she writes. Not having a white “friend” who is willing to vouch for you or testify on your behalf could determine one’s fate, and this is why, as Hurston points out, any Black southerner who is “worth the powder and lead it would take to kill them” keeps white “friends” as life insurance (5, 4).3

Hurston offers a keen analysis of the idiosyncrasies of Black cultural dynamics, values, social types, and subtexts. Of the Pet Negro’s opposite—the Black person without white friends— Hurston extrapolates the following: “They belong in the ‘stray n—-r’ class, and nobody gives a damn about them” (4, 5). This anti-Black apathy, Hurston argues, is shared by the white authorities and the Pet Negroes who collaborate to leave “strays” behind to fend for themselves amid pervasive structural neglect. And yet, Hurston assures that where the Pet Negro is concerned, the wider Black consensus is neither unilaterally critical nor entirely reverent. Though the Pet Negro enjoys much leniency within a culture that has been compelled not to report on our own, Hurston assures us that the treasonous can be and are still rebuked for their crimes against a constructed community. “We curse him for a yellow-bellied sea-buzzard, a ground-mole and a woods-pussy, call him a white-folkses n—-r, an Uncle Tom, and handkerchief-head and let it go at that” (7), she writes.

In drawing on this rebuke of the Pet Negro, we look to Hurston’s essay to reframe these acts of betrayal as a primary function of the petting system and not merely a matter of uniquely greedy or cowardly Black individuals. The system depends upon its prosperity gospel of exceptionalism to train up its pet class. Thus, the “dangers in the system” are essential and cannot be reformed by the contentious matter of the “integrity of the Negro so trusted” (8). What the pet makes into “personal profit” is not, in fact, as Hurston asserts, that which was “meant for the whole [Black] community” (7); rather, it is the surplus of what white communities in the South, especially those with financial wealth, have hoarded and later allocated as their budget for pet allowance. Within this white-controlled system of allowances, the greatest offering presented to the Pet Negro is found not in the material value of any individual allowance but rather in the fantasy of solace that allows each pet to, in the words of media studies scholar Jared Sexton, “distance oneself from blackness in a valorization of minor differences that bring one closer to health, life, or sociality.” This psychic comfort afforded by pethood is facilitated by anti-Black antagonisms. It is not the mark of the pet’s idiosyncratic villainy but rather the way Blackness itself is constituted by one’s availability and vulnerability to a host of non-Black desires and pathologies. Sustained by a violent order of codependence, the Pet Negro is thus better termed self-less than selfish.4

Writing within the “afterlife of slavery,” neither Hurston nor I can take for granted the category of the “self” in critiquing the purportedly self-interested actions of Black slave descendants in the American South. If, as literary scholar Saidiya V. Hartman asserts in Scenes of Subjection, the discourse of agency calls upon the slave to speak “the master[’s] truth,” then one would be remiss to ignore the hegemonic force that enlists the enslaved and their descendants to “disprov[e]” the suffering of those who share their subject position. Without masters, there would be no slaves. A pet without an owner is a pet no more.5

Interestingly, rather than identifying the white benefactors of the Pet Negro system as owners, Hurston refers to them as “friends” (8). In doing so, she implicates interracial friendship—a highly precarious social and emotional exchange between the unequally yoked—as a feature rather than a bug of the Pet Negro system. She also notes her own ties to the white art establishment and its patronage systems. “I have white friends with whom I would, and do, stand when they have need of me, race counting for nothing at all. Just friendship. All the well-known Negroes could honestly make the same statement . . . Carl Van Vechten and Henry Allen Moe could ask little of me that would be refused” (8), she writes. Nonetheless, Hurston asserts that this “petting system” of interracial relation constitutes a network of “underground hook-up[s]” (6) that create an unofficial (though culturally maintained) system that safeguards white power through gestures of anti-Black affection. The incorporation or embrace of select Black people is, thus, vital to the system’s greater scheme of domination.

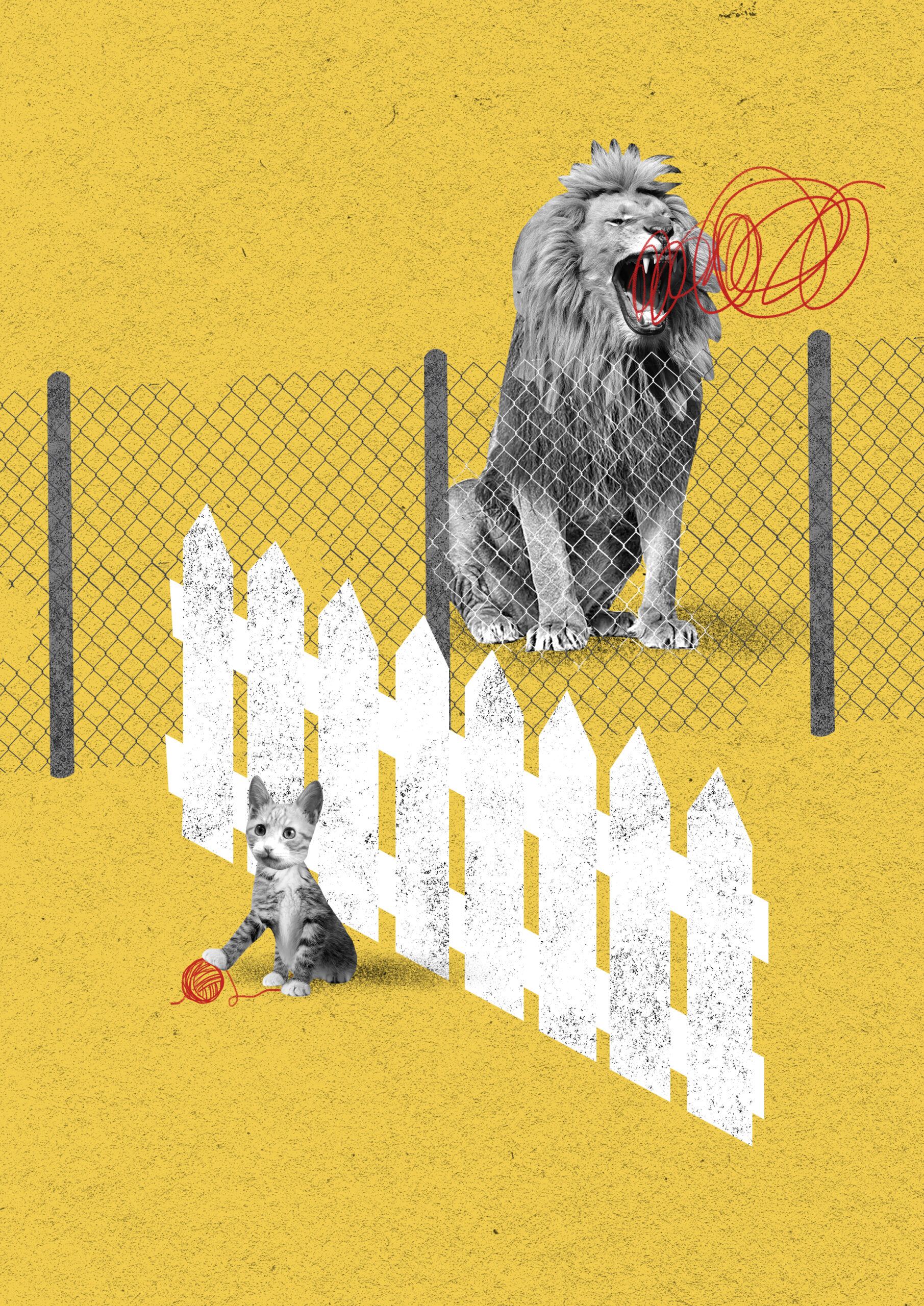

With this in mind, Hurston situates the South’s efforts to uphold this order as one that relies upon the figure of the Pet Negro to serve as a crucial informant who is, by design, expendable and prone to casualty. By providing white communities with valuable insight into the affective and political state of Black communities, the Pet Negro delays their own liberation by helping to prevent the very “hasty explosions” (8) of retribution or resentment that could unmake the southern social landscape. In keeping this bubbling tension of racial conflict at bay, these “friendships” (8), or pet-owner relations, are integral to the vision of the South that Hurston cites in her Book of Dixie. By affording their special Pet Negro with privileges denied to other Black people, the white southerner cashes in on an economy of desire that undergirds the intimacy of race relations, thereby fulfilling their need for a “structuring paradox” of domination which claims interracial affection and narratives of caretaking as tools in its arsenal. It is no accident, after all, that George Fitzhugh’s 1854 argument for the preservation of slavery in Sociology for the South hinges on a discourse of moral development, friendship, and intimacy: “Slavery opens many sources for happiness and occasions and encourages the exercise of many virtues and affections which would be unknown with out it. It begets friendly, kind, and affectionate relations.”6

Yi-Fu Tuan’s Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets integrates discourses of friendship and dominance as they concern the pet as a category which humanist readings have generally reserved for non-human animals. Tuan’s intervention presents a new definition of pethood. As a corrective, he names one class of pet that is animal and another that is human, the two differentiated only in the case of death. “The place which the human friend filled in your life remains forever empty; that of your dog can be filled with a substitute,” he writes. His distinction between the “human pet” and “animal pet” is not reliant upon a scientific argument of differentiation but rather a social and emotional value system that posits the human as unique and irreplaceable, and the animal as one which can be substituted for another of its kind. Betraying a lingering endearment to humanism despite his critique of it, Tuan’s theorization of the human-pet versus the animal-pet suffers greatly where matters of anti-Blackness and racialization enter the discourse.7

Hurston’s configuration of the Pet Negro is born of a discourse in which the animal as a figure of bio-social subjection has long been tethered to the question and questioning of Black (non)being. As Hartman, Hortense Spillers, and Tiffany Lethabo King have all theorized, “Black fungibility” supplants the irreplaceability of the “human” by clarifying the ways that Blackness (and Black people) exist as malleable social commodities defined by imposition, instrumentalization, and reconstitution. Fungibility is, thus, an invaluable theoretical tool for excavating the racial infrastructure buried beneath Tuan’s assumption of the human-animal hierarchy. Black theorists of the human and the animal have taught us that the (im)possibility of the human-pet was realized and exacerbated through the material, imaginative, and intellectual history of anti-Blackness and the transatlantic slave trade.8

Furthermore, the particular history of animals trained to attack and hunt enslaved Black people illustrates a dynamic between the animal-pet and the slave that Tuan’s argument for human-pet distinction cannot account for—a shared condition of fungibility that works to sic the former onto the latter. Sara E. Johnson notes, in her writing on the popularity of Cuban slave-catching dogs in the eighteenth century, that the value of a pet within a slave society is in its potential to be trained by terror in order to enact terror. She observes, “The method of brutalizing the dogs in preparation for their tasks made them such sought-after commodities that Cuban torture methods came to signify effectiveness in the regional imaginary.”Bytraining their pet attack dogs using neglect, brutality, and delayed gratification, Cuban slave-catchers in this colonial period demonstrated how the owned and trained animal is (in)valuable precisely because it is subject to violence whilst being enlisted in violence against designated others: “Both the dogs and their chasseurs were commodities, as the dogs alone were of no value without their masters,” Johnson writes.9

In the twentieth century, when Hurston theorized the Pet Negro as a way to articulate the conditions of Black life and death in the southern United States, she was building upon the very archive Johnson takes up, one in which discourses of Black (in)humanity and animality in the Americas reveal how Black captivity begets interspecies fugitivity and counter-insurgency. Together, Johnson and Hurston’s respective works tend to the interspecies, interracial, and intramural conditions of pet-making by critically engaging the structures and methods that facilitate ownership and training. In doing so, they call us to contend with the regimes of power that overwrite this dynamic model of pethood. Pets are made by relation—purchase, caging, leashing, training—long before they are bred into biological distinction. Discipline, hierarchy, and subjugation undergird the pet’s very existence. These preconditions are what secure the pet’s status as an object of care, casualty and, co-conspiratory potential.10

Where, then, does this leave Hurston’s Pet Negro? If the social valuation of one’s death and the perception of one’s interchangeability are the bedrock of Tuan’s distinction between the human-pet and the animal-pet, the Pet Negro makes its home in the “position of the unthought.” Blackness ensures that the Pet Negro, for all its alleged and actualized comfort and allowance, remains caught up in the storm of violence caused by fungibility. For, if anti-Blackness is, in the words of Christina Sharpe, “the weather” that determines the social, political, and material climate of Black life, there can be no true shelter for the Pet Negro—even the domesticated will face the downpour.11

Writing about how animals feature in human domestic imaginaries in his 1980 essay “Why Look at Animals?,” art critic John Berger articulates the shifts in power relations that have reconstituted human-animal interaction across time, particularly within Western cultures. Zeroing in on the eighteenth-century advent of the European zoo—a site to which displaced and alienated animals are caged and spectacled for public consumption—Berger uses the story of a British citizen who wished to “cuddle a lion” to outline the complex social dynamics between humans and animals that produced the request and its aftermath. As the account goes, a London homemaker named Barbara Carter “won a ‘grant a wish’ charity contest, and said she wanted to kiss and cuddle a lion.” Carter was later invited to the zoo to realize her wish and was subsequently mauled—her advances rejected by the encaged animal, who put Carter “in the hospital in shock and with throat wounds.”12

Berger’s citation of this incident offers a valuable intervention into traditional readings of the imperial domestic sphere and the position of the zoo animal as a kind of public pet. In granting Carter’s (absurd) wish, the British zoo attempted to expand the “geographies of power” accorded to the white homemaker, as a raced, classed, and gendered subject of empire, to the lion’s dwellings. Not unlike the southern US plantation household, which was “the principal site for the construction of southern white womanhood,” the British zoo here functions according to a project of domestication that relies upon the logics of dominance and affection. This sequence of events, which begins with an initial disregard for the lion’s own impulses or temperament, leads to Carter’s mutilation. Here, the public pet’s violent rebuff clashes with a white fantasy of domestication. In bridging the pet-making promise of the national zoo with the project of British domesticity, we arrive at a discourse where the histories of the zoo and the plantation meet.13

To realize her wish to “kiss and cuddle a lion,” Carter first had to disregard what is known about lions—particularly, their ferocity, strength, and capacity for autonomy. For the purposes of realizing her dream of forced interspecies intimacy, Carter sublimated a desire for power into the socially accepted form of a “wish.” The perversity of the request, and her disregard for what is considered common knowledge about lions, is reconstituted as an innocent desire for affection that makes little consideration for the creature’s own receptiveness to human interference. An analysis of fantasy clarifies why both the wish-granting charity and the zoo accept Carter’s request. Carter was not the only one fantasizing about animals. A history of exploitation shaped the culture of human–animal relations in which she cultivated her desires.14

As Berger points out, Carter’s wish to pet the lion is a direct byproduct of a cultural belief in the absolute authority of humans within human–animal relations. The lion’s status as a zoo animal and as a public pet enabled Carter’s wish and its fulfillment. The zoo as an institution is crucial to the production of species identity as well as narratives of interspecies engagement. Just as the zoo teaches humans about animals, it also teaches humans about themselves. Through coercion, marketing, and architectural enclosures, the zoo remakes the human–animal distinction to suggest that, though all animals are not pets, any animal can be haphazardly confined to the role of a pet in service of an institutionalized fantasy. The zoo is but a theater for this dominant interspecies script.

The lion’s rebuff thus shows how this Western animal–human/pet–owner relation is defined by the delusion that a given animal or pet’s capacity for resistance to this order is either tamable or unimaginable. The zoo animal’s attack on Carter upends the fantasy that pets of all kinds, whether they’re private domestic property or confined animals arranged for public viewing, do not recall or desire any existence other than pethood. In Carter’s case, the lion was expected to behave as a public pet, based on a very particular culture of training and dependency that defines zoo life. Yet, even as the animal was primed and coerced to participate in Carter’s wish-fulfillment process, neither Carter nor the zoo staff fully anticipated how the lion’s animal desires would square with their human ones. This inability to fathom the refusal of their domestication fantasy proved to be an especially dangerous oversight.

Through Hurston’s Pet Negro and Berger’s lion, we arrive at an understanding of dominance that defines the pet as a class without the capacity for consent but with a definitive propensity for both counter-revolutionary violence and violent resistance. The pet does not choose but is chosen. The pet cannot consent to giving or receiving affection but is bound to these relations. Of the Black slave’s encounter with consent, Hartman writes, “the simulation of consent in the context of extreme domination was an orchestration intent upon making the captive body speak the master’s truth as well as disproving the suffering of the enslaved.” Paradoxically, consent here is coercive. The slave is offered consent only as means of cosigning their own bondage. To paraphrase Anthony Farley, unfreedom is, in fact, the condition of consent for the slave. In this way, by “bow[ing] down before its master,” the slave is made to sign their own death certificate. Thus, the slave’s efforts at resistance against their master must be, first and foremost, non-consensual.15

As Hurston’s essay addresses the slave descendant as a figure plagued by slavery’s sinister legacy of domestication, affection, and intimacy, the deadly futility of consent emerges once more in the matter of resistance. In her theorization of the Pet Negro system, Hurston situates the pet as an abject minority who aims to preserve its own imperiled prestige through associations and affiliations with white security. Still, as she notes, the pet is more of an accessory than an agent of the system’s preservation. “Both sides admit the general principle of opposition, but when it comes to putting it into practice, behold what happens. There is a quibbling, a stalling, a backing and filling that nullifies all the purple oratory” (5), Hurston writes. As her theorization shows us, resistance is crushed not only through violence but also through strategic forms of care. It is the South’s interracial network of Pet Negroes and white friends that harbor social secrets and manage political moods so as to preserve the South’s own existence. In accordance with this model, the Pet Negro is a multi-purpose scapegoat. The destruction of the South that would be assured by the “explosion” of an imagined race war is said to be extinguished by the pet, therefore the containment or fostering of revolution rests upon the pet’s affective orientation toward affiliation.

As we know, pets gnaw away at the social contract of pet–owner affiliation in their own way. Infamously liable to destroy the trappings of the home when their owner is unsuspecting or absent, it is often only upon their owner’s return to an undone domestic sphere that the pet’s interiority is revealed. Domestic upheaval thus evidences the pet’s resistant potential, which each owner must struggle to thwart. Just as Carter’s wounds are evidence of the lion’s capacity for rejection, the destruction of the domestic space constitutes the realization of the pet’s radical potential. As a derivative of the pet, the figure of the zoo animal lights the way from Tuan’s “human pet” and Hurston’s “Pet Negro” to the intersection of animal studies and Black studies. If the lion’s refusal tears at one kind of Western delusion, Black domestic life and death on and after the plantation—which reminds us that the possibility of violence is not limited but expanded by variations in social geography—fissures the fantasy of domestication that conflates comfort with a liberated condition.

Through Hurston’s analysis of the Pet Negro system, we come to see how the organizing geo-logics of the plantation as a site for identity reformation, affiliation, and fantasy enactment defy time and space before and after Emancipation. Written at the tail end of the First Great Migration, Hurston’s elaborate analysis asserts that the cultivation of Black (dis)comfort and (in) access are integral to southern racial politics, though their power as training tools far exceeds the Mason–Dixon Line. Her North–South distinction is thus a subtle one rather than a structural one. “The North has no interest in the particular Negro but talks of justice for the whole. The South has no interest, and pretends none, in the mass of Negroes but is very much concerned about the individual” (2), Hurston writes. Though the South is crucial to her referential and intellectual project, Hurston remains clear that the emancipated Black subject remains trapped within the “geographies of containment” produced first by slavery and secondarily, by the discourse of “justice” (7), which emerges in the period following Emancipation in which the Reconstruction era takes shape. And since it “still remains true that white people North and South have promoted Negroes” (7), Hurston’s Pet Negroes too are defined by relation rather than region alone.16

Through her classifications of the “Pet Negro” and the “stray n—-r” as subjects of a system that orders Black life throughout the US social landscape, Hurston enters into the fraught relationship between Black studies, humanism, and animal studies to expand the discourse of anti-Blackness beyond the discursive to the ontological, moving from the social to the material and the metaphysical. Hurston’s “The ‘Pet Negro’ System” contests notions of a coherent Black “community” (7) by recasting us as an assortment of pets and strays. She names the figure of the Pet Negro to illustrate that care and allowance are vehicles for mobilizing structural dominance rather than deviations from the logics of anti-Black worldmaking. Hurston’s rhetorical hybrid, the Pet Negro, proves that affection does not preclude antagonism. Nine years before Frantz Fanon would assert that, “to us, the man who adores the Negro is as ‘sick’ as the man who abominates him,” Hurston’s essay established her intellectual arrival to this very conclusion.17

The stray majority is, in Hurston’s estimation, situated within this very same anti-Black politics of neglect and care, abomination and adoration. Strays, however, are vulnerable not only to the bondage of pethood but also to all forms of captivity that make the world into a pound. Hurston refuses to romanticize the stray in her critique of the pet’s indulgence. Critical and careful in her consideration of the conditions of Black life, she articulates just how anti-Blackness trains us all. For, as she asserts, there are strays who dream of pethood—those who, in their systemic discomfort, are called to desire domestication rather than freedom. Hurston theorizes the ways that comfort corrupts the pet’s radical potential without presenting the uncomfortable position of the stray as one imbued with inherent liberatory character. By the essay’s close, neither the pet nor the stray are enlisted as a “placeholder for freedom.” Hurston knew better. Her political imagination could not be leashed by the comforts such a concession might grant.18

This essay was published in the Moral/Economies issue (Winter 2022).

Jordan Taliha McDonald is a PhD student at Harvard University studying Black literature(s) in the Americas. Her scholarly work considers how narratives of betrayal are theorized under conditions of slavery and state violence. Her culture writing has appeared in Vulture, New York Magazine, Artsy, Blacks Rule, and more.

NOTES

- Zora Neale Hurston, “The ‘Pet Negro’ System” (United Kingdom: Wildside Press, 2019), 2. Originally published in The American Mercury, May 1943. Page numbers hereafter included in-text; Lyndrey A. Niles, “Rhetorical Characteristics of Traditional Black Preaching,” Journal of Black Studies 15, no. 1 (1984): 41–52; M. Cooper Harriss, “Preacherly Texts: Zora Neale Hurston and the Homiletics of Literature,” Journal of Africana Religions 4, no. 2 (2016): 278–290; Dolan Hubbard, The Sermon and the African American Literary Imagination (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1994).

- Episcopal Church, The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church: Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David According to the Use of the Episcopal Church (New York: Seabury Press, 1979).

- E. Franklin Frazier, Black Bourgeoisie (New York: Free Press, 1965), 236.

- Jared Sexton, “Ante-Anti-Blackness,” Lateral 1 (2012), https://doi.org/10.25158/L1.1.16.

- Saidiya V. Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008); Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- Xine Yao, “The Babo Problem: White Sentimentalism and Unsympathetic Blackness in Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno,” in Disaffected: The Cultural Politics of Unfeeling in Nineteenth-Century America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 29–69; George Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, or, The Failure of Free Society(Richmond, VA: A. Morris, 1854); Patrice A. Douglass, “Belle’s Beloved: Hauntings, Feminized Slave Ships, and the (Im)possible of Writing Black Women” (paper presentation, Black Feminism Beyond the Human, Duke University, January 29, 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eKlyq3itFSM&t=4849s.

- Yi-Fu Tuan, Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984), 88–114, 141.

- Saidiya V. Hartman, “The Belly of the World: A Note on Black Women’s Labors,” Souls 18, no. 1 (2016): 166–173; Joshua Bennett, Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020); Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World (New York University Press, 2020), 1–44.

- Sara E. Johnson, “‘You Should Give Them Blacks to Eat’: Waging Inter-American Wars of Torture and Terror,” American Quarterly 61, no. 1 (2009): 65–92, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.0.0068.

- Hortense Spillers, “Black, White and in Color, or Learning How to Paint: Toward an Intramural Protocol of Reading,” in Black, White, and in Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2003): 279.

- Saidiya V. Hartman and Frank B. Wilderson, “The Position of the Unthought,” Qui Parle 13, no. 2 (December 1, 2003): 183–201; Christina Elizabeth Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 102–134.

- John Berger, “Why Look at Animals?,” in Why Look at Animals? (London: Penguin, 2009), 12–37.

- Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 63–96.

- Berger, Why Look at Animals?

- Hartman, Scenes of Subjection; Anthony Farley, “Perfecting Slavery,” Loyola University Chicago Law Journal 36 (2005): 225–256.

- Regarding geographies of containment, see Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 12–34.

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skin White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (London: Pluto Press, 1986), 10.

- Hartman, “The Belly of the World.”