The following is an excerpt from Country Queers: A Love Letter (Haymarket Books, 2024) and has been lightly edited to appear on Southern Cultures in collaboration with the Queer South issue.

Early in the spring of 2014, I borrowed a neighbor’s video camera and recorded myself, with my ducks hanging out in the background, rambling about my dream of traveling around to gather rural queer oral histories. I launched a Kickstarter fundraising campaign to support a month long road trip in the summer, when I’d be off from work in the public schools. I honestly didn’t think it would work.

But it did. The donations started pouring in, as did enthusiasm for the project. I received emails and messages from people all over what is currently known as the United States, and beyond. People in Italy and England wrote saying how much they loved the idea. Folks in Montana, Texas, Florida, Mississippi, and North Carolina invited me to their towns. I sent a mass email to every queer person I knew, reached out to LGBTQIA2S+ organizations in states I thought I might pass through, and, out of endless possibilities, a route emerged.

I spent mid-June to mid-July on the road in a used Subaru Forester with over 160,000 miles on it (and a sizeable loan). I had a flip phone and a paper atlas, a Zoom H4n audio recorder with no external mics or fancy headphones, and a Canon digital SLR camera I purchased with some of those Kickstarter funds (along with a tent, sleeping pad, and small camp stove). Covering seven thousand miles, I interviewed thirty people in thirty days. In Mississippi, Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and Oklahoma, I slept on the couches and floors of people who shared their stories with me. All the butches grilled for me in the summer heat. Autumn in Angleton, Texas, baked me a birthday cake and had it waiting when I arrived late on a June evening, after a long day of interviewing and driving. Autumn and her then-partner also took me to their favorite Tex-Mex restaurant, to the sno-cone stand they ran together, and down to the brown waters of the Texas Gulf where we watched seagulls fly, oil tankers float by, and people catch huge fish. People sent me on my way with homemade baked goods. They invited their friends over to meet me and share meals. I met people’s parents and kids, partners and housemates, pets and livestock. Mattie, who I interviewed in Alpine, Texas, put me up for the night at the nicest hotel I’d ever stayed in—knowing I’d already been on the road nonstop for days and hadn’t had much time alone. I also camped in my tent along the way. I got to visit friends in Austin and Denver on a couple days off. I took a weekend off in New Mexico—and soaked in a hot spring high up on a mountainside. I got to help Courtney in Kansas with evening goat-milking chores after our interview.

Everyone took such good care of me, in the way that country queers always do. I didn’t think of it at the time, but now I bet many of the folks, particularly those older than me, were worried about me out on the road traveling solo in an old car with a flip phone. There were moments of fear on some stretches of road or in certain motel parking lots at night. I ended up sleeping in hotels more than I’d planned to, after realizing that I felt most comfortable camping alone (without my dog) if I was able to arrive in the daylight and get a sense of my surroundings and neighbors before the sun set, which long travel and interview days didn’t always allow for. Since I had no GPS or smartphone, I’d spend an hour in the morning before leaving the hotel looking up Google map directions on my laptop and writing them down by hand in my notebook. Miraculously, I didn’t ever get a flat tire or break down. No one physically harassed me, and I successfully dodged all the advances of overly curious men. Somehow, I didn’t even get drastically lost along the way. Someone, somewhere, was looking out for me.

I drove through thick, humid nights in Mississippi, dry, sunny days in West Texas, dramatic thunderstorms in New Mexico, glaring brightness in Colorado. I traveled mostly on two-lane highways, listening to burned CDs on repeat. Amy Ray’s first country album, Goodnight Tender remains the soundtrack of that trip in my memory. I still regret not stopping for a picture in the high desert of southern Colorado, where along a long stretch of flat highway with a view of the Rockies in the distance, for at least thirty miles someone had spray-painted little black UFOs on every cow-crossing sign.

I was homesick and exhausted but also blown away, again and again, by how welcoming and vulnerable everyone was. When I arrived back home in late July, I crashed hard. I felt like I’d had an IV in my arm all month long with a strong and constant flow of other people’s memories. I didn’t know how to talk about the decades of other people’s stories—that were somehow also our collective rural queer history—swimming around inside my head and heart. I am an introvert, and the exhaustion at the end was intense.

That trip wasn’t a sustainable model, but it was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. I’m incredibly grateful to each person I had the true honor of meeting along the way.

This is the longest section of the book, because of the abundance of interviews gathered in that time. In the early days, I’d interview anyone who got in touch wanting to share their story, so most interviews were gathered in those first two years. In the pages ahead, you’ll meet ten people I interviewed that month. Several of the excerpts include accounts of traumatic events and experiences, including threats and realities of physical violence and death from HIV/AIDS. You’ll notice that two of the excerpts are significantly longer than the others, to allow space for accounts of broader historical events and contexts.

Sandra Vera, she/her, 43 years old

Karankawa, Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan, and Esto’k Gna (Carrizo/Comecrudo) lands

Lake Jackson, Texas

June 20, 2014

If I remember correctly, I got connected to Sandra through the unparalleled lesbian phone (or in this case, email) tree. I think my friend in Texas put me in touch with a friend of hers in Florida, who put me in touch with an older lesbian in middle Tennessee, and someone else in Texas who put me in touch with Sandra. Anyway, it is a fact that lesbians pre-internet were impressively well connected and organized via snail mail newsletters and phone trees. Sandra and her wife, April, were incredibly sweet to me. I think they probably thought I was a bit crazy to be out on this trip (which was true). I will always be grateful to Sandra for rescuing me from the nest of fire ants I stepped into in sandals while making a picture of them on their front porch.

Sandra Vera: It’s a very Christian-oriented town, Lake Jackson is. We’ve got what we call Church Alley. People for the most part are friendly. It’s near the coast. That’s about it! Not a whole heck of a lot going on in Lake Jackson.

I identify as a lesbian. My whole life I’ve been a tomboy, but I’ve never identified as a boy. The very first person I ever told that I was gay was my best friend, Rhonda, who I grew up with. She is also our roommate, but she’s not here today. It wasn’t until high school, when I was probably sixteen or seventeen, when people close to me knew. My sister was like, “I already knew.” My brother never expressed any type of opinion about it at all. He and my sister-in-law have always been very accepting of my girlfriends. I was Dad’s shadow, so if he got in his truck to go to the dump, I was in the truck going with him. If he was working on the roof, I was beside him working on the roof. I think he might not have been so surprised.

I work mostly with men. There’s only one other woman that’s a technician in my block. The men that I work with, 90 percent of them are Christian, conservative, hunting, fishing, good old boys. I seem to fit in with them though. It took a while for them to get used to me being around. I was obviously out. I didn’t have anything to hide. At first, I didn’t feel like I was very respected by them. First of all, you’re a female in the workplace where—it’s a boy’s club in there. But now it’s a totally different feeling, nine years later. I’ve been working with those same guys, and they’re like brothers now, and being gay, being a woman in that workplace—it’s fine for me. I haven’t had any issues.

The plant that I work at is one of the leading chemical manufacturers in the world. It’s a German-based company, and at our particular site we make over twenty-two different products. I work in the heart of the whole plant, which is the utilities department. In the department, we have pressure steam and distribute it throughout the whole plant in a cogeneration unit. A cogeneration unit not only makes this high-pressure steam, but the byproduct of it is electricity, so it makes eighty-five megawatts of electricity. All the plants also have a wastewater stream that comes to us. It’s either high or low PH, or real acidic, alkaline. We’ll take it, and we’ll treat it to the specifications of the state and governmental regulations. The other aspects are making deionized water and keeping up with the infrastructure of the plant as far as the pipelines, the river water, the potable water, the DI water from gate to gate, the whole plant.

Rae Garringer: Cool! I don’t know what most of that means.

SV: Makes for a long day is what it means.

RG: Did you ever know about any gay people in the area when you were growing up here?

SV: When I was probably five years old, my dad . . . he worked in the chemical plant too, but he also did side jobs. And he cut the grass for these two older women who lived together. I was always very interested in the dynamic there, and if he was going to mow their yard, I was going. I wanted to be around them. There was something that attracted me to them. But I don’t think they ever were out as a couple. It seems like I vaguely remember my parents talking about it. But as far as the other people that I’ve known throughout my life who were much older than me that I knew were gay, or suspected of being gay, they were not out. There was an older lady from this area who was married to a man just to be married to a man, but she was lesbian. And she said, “I married him because that’s what I was supposed to do.” So we’ve existed around here, but I think long ago was a lot harder to be out and open about it.

I probably only spent two or three hours with Sandra and April, but I remember laughing a lot, and wishing I lived closer ’cause they seemed like people who knew how to have a good country time (boats! four-wheelers! dogs!). I love how Sandra describes not feeling tension or conflict around her sexuality in relation to her local community. Sandra is one of the narrators whose stories disprove the pervasive stereotype that rural queer people’s lives tend to be full of harassment and violence. Across differences in gender, race, and ethnicity, many people told me that they haven’t had significant issues in their towns and that their communities mostly treat them well. In the beginning of this project, my questions skewed heavily toward asking what issues and challenges rural queer people faced, but many narrators, including Sandra, taught me that those weren’t necessarily the right questions to ask, and that our struggles aren’t the only interesting or important things to talk about.

Rae Garringer is a writer, oral historian, and audio producer based in southeastern West Virginia, where they were raised. They are the author and editor of Country Queers: A Love Letter and the editor of To Belong Here: A New Generation of Queer, Trans, and Two-Spirit Appalachian Writers. When not working with stories, Rae spends a lot of time failing at keeping goats in fences, swimming in the river, and two-stepping around their trailer.

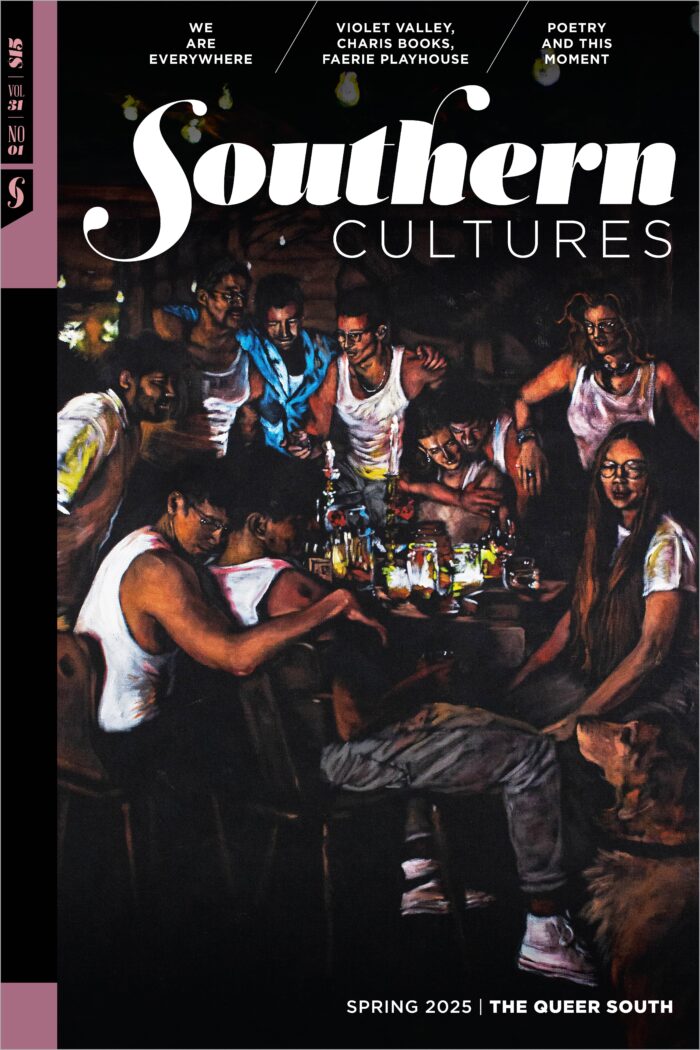

Header image: The Desk, Alpine, Texas, 2014.