“I think that white voters in the South are more nuanced than people think. I know that Black voters are more nuanced than folks think. And we have to begin to engage with the electorate in a different way because folks don’t want to engage with the South, but the South engages with you.”

Courland Cox, a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the 1960s, facilitated an April 7, 2023 conversation online with Nsé Ufot, former executive director of the New Georgia Project, and Charles V. Taylor Jr., executive director of the Mississippi State NAACP. Part of the “Our Stories, Our Terms” grant project, sponsored by the Movement History Initiative and funded by the Mellon Foundation, this intergenerational conversation explores key issues in today’s national politics, especially the role of southern Black and Brown voters and strategists.

During his work with SNCC, Cox participated in sit-ins, supported freedom rides, and worked on voter registration in Mississippi and Alabama. He played a key role in SNCC’s political organizing work in Lowndes County, Alabama, which led to the establishment of the Lowndes County Freedom Party and the national call for Black Power. After SNCC, he was a founding member of Drum and Spear Bookstore and Publishing Company, helped organize the Sixth Pan-African Congress, worked on minority business issues for the District of Columbia, and was the director of the Minority Development Business Agency at the Department of Commerce. He is presently serving as Chair of the SNCC Legacy Project.

Nsé Ufot was born in Nigeria and raised across the street from a housing project in Atlanta, where she became a naturalized citizen in high school. The daughter of immigrants, she excelled in school and became a corporate attorney before meeting Stacey Abrams and following her passion into politics. She played a central role in helping Georgia elect its first African American and first Jewish senators, while giving the Democrats a key victory in the 2020 presidential race. Charles V. Taylor Jr. has a passion for politics, justice, data analysis, and Mississippi. He was the field director and campaign coordinator for the 2015 Better Schools, Better Jobs Ballot Initiative 42, a heroic effort to amend the state Constitution to require equitable educational funding for all of Mississippi’s young people. Though it fell just short, there is still much we can learn from the effort. Taylor was a founding member of Freedom Side, and he has worked closely with the Mississippi NAACP, while learning many political lessons from his daughter.

Cox brought together Ufot and Taylor, whom he considers two of the “brightest minds around,” to share their insights about the significance of southern voting and politics at the local and national stage. This intergenerational conversation explores the connections between the past work of SNCC and present-day political activism, highlighting the ongoing need for effective organizing, even as technologies evolve. Cox and the younger political analysts make a compelling call for a New Southern Strategy, one that builds Black political power and assumes the centrality of southern Black voters and leadership in the Democratic Party’s hopes for national success.

This version includes the full conversation, including an online-only section.

Courtland Cox: I’m going to take us back to 1965. SNCC wanted to achieve two objectives when it started working with the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. First, SNCC was trying to fight for the right of Black people in Lowndes County, Alabama, to register to vote. Lowndes County had a population that was 80 percent African American and there were zero Black people registered to vote in Lowndes County. The second objective SNCC wanted to achieve was to encourage the use of the Black vote, to get the newly registered voters to run for political office in the County.

SNCC organizers were trying to get the Black residents to go from zero—no one registered to vote—to sixty, holding every political office at the County level in one election. We asked ourselves how do we, not only just get people registered, but also get people to run for all of the offices—the sheriff, the board of education, tax assessor, tax collector, probate, judge, all these positions. The Black people of Lowndes were in a political environment where white supremacy was not hidden. The Democratic Party in Alabama had on its logo “white supremacy for the right.” And we had to create a political fight within that particular environment.

So, Nsé, I’d like to ask you to talk about what you were trying to do in Georgia? What were the political objectives and why were you trying to do it?

Nsé Ufot: I grew up in the Georgia Democratic party of the eighties and nineties. And it was Dixiecrats, it was southern conservative Democrats, and southern conservative Republicans, and then a handful of well-to-do elite African American lawyers and business folks who operated essentially by a number of gentlemen’s agreements that impacted all of our lives. When we launched the New Georgia Project, there were some very material, real-life conditions that we were trying to address. Like the fact that the minimum wage in Georgia was $5.15 an hour, well below the federal minimum wage of $7.25. And it had been nearly two decades since Georgians had had a raise. That we had not had Medicaid expansion. And that in Georgia’s 159 counties, less than half of them had obgyns; several Georgia counties had no doctors at all. And that the Black maternal mortality rate in Georgia was the highest in the country and rivaling that of developing nations. Our state leaders were completely unresponsive. Poll after poll after poll showed that folks wanted Medicaid expansion. Poll after poll showed that we wanted an increase in the minimum wage that approached something like a living wage. And it was falling on deaf ears, even though we were organizing folks and they were voting. Still the elected leaders were not moved. And so instead of being mad and being upset, we were like, we have the ability to fire these folks. How do we do it?

Stacey Abrams commissioned some research and found out that there were 1.2 million Black and Brown folks in Georgia who were eligible to vote and completely unregistered. That number mattered because, at the time, the successful Republican was beating the losing Democrat by about 250,000 votes statewide. So when the New Georgia Project launched, there were five times the number of eligible and unregistered Black folk and Latinos and Asians in Georgia who were eligible to vote but were not participating at all—five times what was needed to win any statewide election. And so that felt like an area where we could get in and combine our electoral organizing with what we knew about base building and community organizing and civil rights organizing with boots on the ground to try to do something powerful and impactful that would actually change the material conditions that Black Georgians were experiencing. We didn’t just hop in and say, We wanna register a million Black people, ’cause it sounds like a good thing to do. It was literally a part of the larger strategy to win the things that Black folks told us they needed. And that’s how we got started.

CC: Charles, you were trying to deal with an issue in Mississippi. Tell us what the issue was and give a sense of why you were trying to do that.

Charles V. Taylor Jr.: The conversations about the Mississippi Ballot Initiative, which was in 2015, starts a few years earlier. Derrick Johnson, who’s now the national president and CEO of the NAACP, was at that time the state NAACP president and executive director of One Voice. He was asking: “How do we get people to go to the polls?” And so what Anthony Thigpen of California Calls and others were able to find out is that happened through issues. So Diane Feldman, who was a longtime pollster, did a poll in Mississippi to see which issues folks cared about the most and education was at the top of the list. So then it became a question of, could we legally change our constitution to do something to support education? And so we developed what we now know as Initiative 42. What 42 would’ve done, if it was successful, was two things: One, it would have created a fundamental right to education in the state of Mississippi. Two, it also would have forced full funding of the education program formula.

In Mississippi, we have a constitutional right to a free education as prescribed by the legislators. And what we know about places like Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia is that they do not support folks who look like us, but want an educational system that will let them sell themselves as a state that is available with cheap labor. What was most exciting about Initiative 42 is it would’ve made a systemic change. Mississippi has what you call a Mississippi Adequate Education Program (MEAP), which was developed because you had a slew of lawsuits that happened throughout the South to say that educational funding was not equitable. But, since MEAP was established in 1997, the legislature had only fully funded education twice. Most of the time it was underfunded by a lot. And even adequate funding meant a C school district. So you had a scenario where suburban schools are underfunded, but they would increase the local tax dollars for the school and it would get them over that threshold of underfunding, plus a little more. But in the Mississippi Delta, the school districts would be grossly underfunded. This was the issue that we were trying to resolve. How can we create a systemic solution to this underfunding problem?

I think about something that SNCC veteran Charlie Cobb said over fifty years ago, around December of 1963—that it is universally known that education in Mississippi is grossly inadequate compared to the rest of the country. And it is sad that we are about sixty years from him making that statement and it’s still the case. We narrowly lost that election, but ultimately the fight for education is still here and so is using issues like education through a civic engagement framework.

I’m going to do this work to the day I die. I love Mississippi and we’ve got proud people who wanna make our state better.

CC: Nsé, how did you go about getting the 1.2 million people registered? What were the obstacles, what new tactics and techniques did you have to engage in, in order to get the people to meet your objectives?

NU: Well, I’m happy to talk about the technology that we built—the apps, the video games, and all of that. But I’m gonna argue that the thing that made us most effective is probably the oldest tactic and seems to be a thread and a throughline between your work in Lowndes County in Alabama and Charles’s work in Mississippi. And that is the idea that we were accountable to a base, that we were building power within an identifiable base.

We knew who we were organizing with, and we had absolute clarity about what was a priority to them, what would get them to mobilize, and what would get them to put their feet in the streets. We trained our organizers that you have twice as many ears as you do mouths and that we should be listening. At the core of the work at the New Georgia Project was a very aggressive and a very robust research and technology agenda. The organizing mantra is: You go to where the people are, right? And if we are trying to register young people, if we’re trying to register folks who are living life today, you must have a digital strategy, right? There was a time where it just meant being at the right bus stops, being at the right malls, being at the right outdoor festivals, being at the right churches, being on the right college campuses.

But what it means to meet people where they are has broadened in the world that we live in now, so getting smart about social media felt important. And it was not just so that we could make cool Facebook ads or cool Instagram ads, it was so that we could continue to listen, ’cause people are gonna tell you what their hopes are, what their ambitions are, what their fears are, and again, what they are willing to take action on. And so I think the thing that helped us win is that we were able to demonstrate not just that we had the same identities as the communities that we were organizing with, but we demonstrated our expertise based off of our research. We also raised an extraordinary amount of money in order to do this work and professionalize our operation. I knew that there were gonna be a lot of people who were claiming to register Black people, that what we were doing was intervening and upsetting the status quo. That we were going to find voter suppression and that we were gonna have to have a legal strategy. I knew that they were gonna try to stop us by claiming that we were doing something funny with the money, that we were not run well, that we were not compliant with all the laws of the land. And so we made sure that we had a professional staff, that we built the hard skills of our staff, but also that we were able to recruit people who shared our values and came from the communities that we were organizing with.

We went out to donors and said that this is not a regular campaign job. It’s not the grand opening, grand closing approach, and we’re not going to pay people $10 an hour to knock on doors. We’re gonna pay people a salary with a 401(k) and a retirement plan for our organizers, which means that the New Georgia Project’s gonna have a professional development budget. We are developing the skills that we need to run and win the campaigns of the future.

We couldn’t find that money in Georgia though. That meant being on the road a lot, spreading the gospel good news about the possibility of a new map, talking to national Democrats who have more money than sense—just keeping it real—and selling them on the idea that with the way that white supremacists and white Christian Nationalism are taking a hold in Ohio and Michigan, that they’re gonna have to look at a new electoral map if they’re thinking about trying to capture the White House in 2016 at the time and then 2020. They need to be thinking seriously about the South because that is where their base is. And Georgia is the tip of the spear. We had no proof of concept, but we had data and a plan, and we got people to invest in a real way.

CC: What kind of money did you have to raise?

NU: Over the nine years I was in charge of the New Georgia Project, we probably came close to raising about $90 million to do the work. And it still didn’t give America its first Black woman governor. It did a lot of things, though. We fired Trump, we gave Georgia its first Black US Senator in Reverend Raphael Warnock, its first Jewish senator with Jon Ossoff. And we elected Ossoff when he was thirty-three years old to the United States Senate at a time where the majority of the Senate was born before there were even fifty states. As we’re thinking about climate change, as we’re thinking about the future of work, as we are thinking about the future of money and the economy and what that means, having a millennial in the Senate—Georgia did that! Black voters in Georgia did that!

I am proud of what we raised, and it wasn’t nearly enough, given the context in which we were doing our work. The Senate runoffs were the most expensive Congressional races in the history of American politics.

CC: So, Charles, all the things that Nsé just talked about, you had to deal with, and in addition you had to think about how you get enough whites in Mississippi to support your program. So tell us a bit about what you had to do.

CT: Like Nsé was talking about, getting the money from outside of the state, that’s true for Mississippi. I think that we are very close to a tipping point in Mississippi. Folks like our former governor, Haley Barbour, recognized that twenty years ago and has done everything he could to eliminate the white Democrat. He recognized that Black voters was gonna stand to their values. It didn’t matter—you couldn’t trick ’em, you couldn’t pay ’em, they were gonna be principled in their vote. But you had this fleeting white Democrat. And he said, “I can functionally eliminate you and make voting in Mississippi polarized by race.” We were bumping up against that with Initiative 42.

The first time in Mississippi’s history that we had more voters in the Republican primary than the Democratic primary was in 2019. And people thought that was shocking because in many areas in Mississippi there was a one-party state of Democrats. But when Black people integrated into the Democratic party, white folks moved over to the Republican party in droves. There were certain places where they would still consider themselves a Democrat. Most of them would probably identify as a Dixiecrat, but you had some crossover on an issue or a candidate every now and then.

The Ballot Initiative election of 2015 was the first time that you had Black and white folks come together on a campaign, and it was tricky, as we would have conversations around engaging Black voters, conversations around engaging white voters. The frustration points were a couple—I’ll speak freely here. We need more white people in the South to stop trying to organize in Black communities and to organize their own. A lot of times whites are much more comfortable organizing in our community than they are talking to their cousins about an election on Thanksgiving.

When it came to Initiative 42, there was some crossover, but they quickly racialized it. So at first it was about educational funding and it’s like, “You mean more money for the public schools? Great!” So then they started racializing it by dog whistling: They said, “Do you really want a Hinds County judge?” And they had this Black silhouette of a judge. “Do you really want this Black man or woman deciding how much funding your school was gonna get?” Even though it wasn’t even true. It would’ve been in whatever local chancery court that they had. But that’s what they started saying, that was their message: “We know this is screwed up, but you know, those Black folks, they’re really gonna screw it up.”

Along with that was the confusion with the ballot. For the first time in Mississippi’s history, they put an alternative on the ballot. Instead of just a simple up and down vote: “Yes, I wanna vote on the Initiative 42 for full funding.” Or “No, I don’t wanna vote for this.” Before you answered that, you first had to vote whether or not you wanted to change the Constitution, yes or no. And even if you decided, “No, I don’t want to change the Constitution,” you had the right to vote whether or not you preferred the citizen-driven amendment or the legislative alternative, 42A. And even before that, they put the two-page explanation on the ballot. Can you imagine a ballot that has a two-page, single-space explanation on there before you answer the question? That was all to create confusion.

So we end up losing the first question, which makes the second question null and void. The second question we won by about 60 percent. But the first question, whether or not to change the Mississippi Constitution, we lost by 22,898 votes. That is a number that I will never forget. It showed how close we were.

A lot of campaigns in Mississippi make a mistake in how they engage white voters—they literally will not talk to ’em. They’ll say, “Oh, we’ll get ’em on television.” TV educates, it does not persuade. But you have to engage the voters. The message could have been perfect, but if no one heard it, then what is it gonna do?

I think that white voters in the South are more nuanced than people think. I know that Black voters are more nuanced than folks think. And we have to begin to engage with the electorate in a different way because folks don’t want to engage with the South, but the South engages with you. Think about Dobbs in Mississippi, which struck down Roe v. Wade. It engages you in Alabama, with Shelby striking down the Voting Rights Act. Over and over and over, the South engages the country. And guess what? People who are elected in some of these places have an impact on the entire country. And so why not create the inverse of that, which is very doable, where we have positive impacts coming out of the South. You know, examples like we have in Georgia, let’s let that happen in Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Tennessee, Arkansas, et cetera.

CC: I’m listening to you and listening to Nsé, and I’m thinking, What was advanced technology fifty-eight years ago? We persuaded people because they saw by example what we did. We lived in the county with them and faced the dangers that they faced. We faced violence as a matter of fact. Guns were everywhere, therefore it was very important that the Black residents saw SNCC organizers willing to work with the constant threat of violence faced by the local residents. We also lived their lives in terms of the food they ate, lived their lives in terms of the housing conditions that they lived in. So we lived in a place that had no indoor plumbing. And we had a water pump outside that we had to pump every morning. The Freedom House that we lived in had one butane gas heater that was not sufficient to heat up the whole place. And there was a hole in the roof. But other than that, we were good. But what was important in terms of persuading local residents to participate politically was our constant presence, and we lived their life.

The SNCC organizers used pens and pencils as the technology to create and educate. Mass production of documents was done on a mimeograph machine. SNCC organizers used their creativity to break down the complex laws that defined the responsibilities of the various political offices. We were trying to get people to become sheriff or tax collector or tax assessor. We couldn’t give them complex laws; we broke down the responsibilities into comic books. Jennifer Lawson was doing stick drawings. The other thing that was important to us was the overall message, because in all these campaigns, winning the hearts and minds of people is really important.

Charles, we used a quote from a woman in Mississippi who said at a mass meeting, “Us colored people been using our mouths to do two things. To eat and say, yes sir, it’s time we said no.” So we developed a book that said to people: When it comes to white supremacy, it’s time to say no. It’s time to exercise your power. And we started talking about power and the need to control the county seat. SNCC organizers took the conversation of achieving political power beyond Lowndes County. We started a discussion about talking to the national Black community about the issue of power.

In 1965, the technologies we used to organize were the WATS line (a wide area telephone service, which meant that you didn’t have to pay call by call), the mimeograph machine, and pen and pencil. We didn’t have much more than that. But it’s great to listen to you guys talk about the technologies and the TikToks—

NU: I would argue, Courtland, that the mimeographs, the cartoons that you did was the Tik-Toks of ’65. That was advanced technology. I would also argue that even if it wasn’t the result of deep understanding of social science research, you knew to make sure there was no daylight between you all and the communities. Y’all didn’t parachute in, you lived there. You broke bread with people. They knew you; you knew them. And that, by far, feels like one of the most important things that we teach our organizers in terms of building trust and building power.

So that felt revolutionary.

CC: I was one of the older people in the group and I was twenty-four years old. So we are talking about people ranging between nineteen and twenty-four taking the leadership in this conversation. Stokely Carmichael, aka Kwame Ture, who worked in Lowndes, was twenty-four. People were invested in us. In fact, they not only saw it as their duty to vote and to participate, but they also felt, given our ages and given the violence of that environment—they made a commitment that they were going to protect us. I think you cannot get any more invested than that, where they would protect you.

So what would you say are the lessons learned? What kind of lessons do you think we should take from this and begin to understand and try to let others know?

NU: Organizing gets the goods. We’ve seen attacks on the court and the weakening of the court. I don’t think that that’s gonna go away. We’ve seen the limitations of electing people when it has not resulted in the things that we wanted to see as quickly as we would like to see. Of course the courts are gonna fail us, elected officials are gonna to fail us. Disinformation and misinformation, sometimes it’s super effective, sometimes it’s not. But organizing will always get the goods, and we have to make sure that there’s no daylight between us and the people. There’s no way around keeping the people confident, informed, and active—in defense of and in pursuit of the things that we want. And that is how we get from one fight to the next and are able to pass the baton.

Generally, when we think about elections, we think about it as electing an individual. But it does seem to me the question is whether it works to elect a person and let that person just by themselves move forward—with no accountability to the community and with no organizing around issues. My sense is that elected officials are there to advance our economic interests, and our economic interest means food, Medicaid, these kinds of things. It’s not enough to be there because you’re a good guy and you can make a good speech. You have to advance our economic interests.

Something that Charles and I have talked about, and other organizers are thinking about, is thinking about a successful election as the starting line and not the finish line, right? Right? So we get an organizer elected and that feels like a win for organizing. But it’s not the victory. You do celebrate the intermediate wins, ’cause social science research tells us that that’s important and a powerful motivator to keep people going. But it was never ever about getting one person elected. It was about all of the things that folks want for themselves, and I think that that’s one of the approaches we need to work on. That gets you out of the heartbreak and disappointment that will inevitably come. You have to realize that the election is the beginning of our work. We elected you because we wanted these things. And so we are here to figure out how to get them.

CT: Along those lines, I wrote this civic engagement framework a few years ago and it started with: You get people excited about an election and they actually go exercise their right to vote. But it ends with a cogovernance model. We gotta have that kind of relationship with our elected officials where it’s not just a threat of: “Hey, we will get you outta office.” But it’s them recognizing that when they do something, they need to reach out.

What that could look like is when you have legislators on the floor and an issue is coming up, they’re texting people like Nsé to say, “Hey, we got this voting rights issue happening, how should we handle this?” Or having the meeting before. If it’s something around Medicaid, they’re talking to these professionals and organizers around public health to say, “Here’s how we address these issues.” And ultimately, we want to get to this cogovernance model where folks recognize that, “Yes, I may be the one elected, but I cogovern along with what the community wants.”

The issue is, oftentimes we ask folks to engage only in an election. I’m gonna talk to you thirty days before, or even six months before. But then the aim and the ask is always “Go vote for this person.” But the aim and the ask is never “Hey, go and do this thing.” And not necessarily always in a protest sense, but moving from a position of power, saying, “The police force wants to know how should they police or how should they interact?” And you are having a community session where you’re telling them, “This is my advice about how it should be.” This is an alternative to having to protest something that they are doing. Ultimately, I think that is where we need to get. The hard part about it is convincing those who can facilitate the dollars that this is what we need to be doing.

NU: I wanna pick up on that point. The lesson I’ve learned is that politics is really the expression of economic interests. Basically, you have people at the bottom who need Medicaid, who need food, who need housing and so forth. And then you have people at the top who don’t need all those things and don’t wanna pay for all those things and feel that government should not spend money on those things that people at the bottom need.

As we begin to look at the politics going down the road, it’s the billions that came into Georgia against millions of votes. If we’re gonna have a democratic society, that’s the back-and-forth. How do we now organize the millions of votes when we know billions of dollars are going to be coming in to oppose the millions of votes?

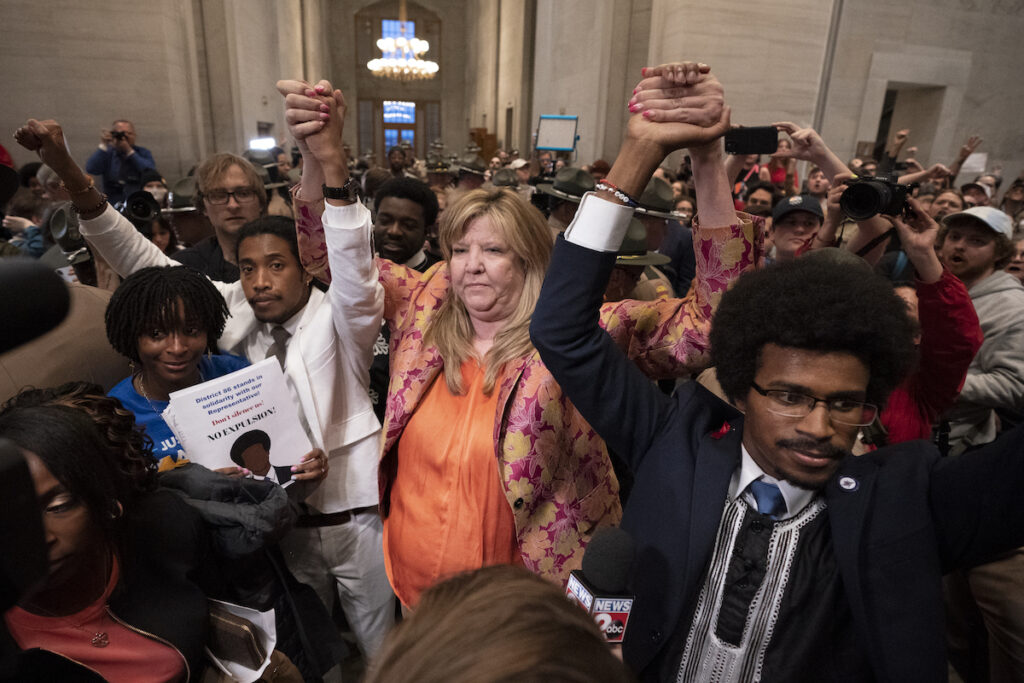

CC: As we fight for human and civil rights, the ability to define and determine the narrative is an important lesson to learn. For example, what happened in Tennessee in early April 2023 when the Speaker of the House said that the young people coming into the chamber to talk about the murders of six people a week earlier was an insurrection that was worse than January 6th. So he put that out there. They created, as Kellyanne Conway would say, an alternative fact, alternative reality. Our narrative was, “No, these mass shootings have to stop because young children are scared to go to school.” So whose definition will prevail is a big discussion.1

Our narratives have to have a worldview about what’s happening in America that goes beyond responding to specifics, incident by incident by incident. What people don’t understand about Trump and all the rest of the maga-ites is that they are trying to establish a worldview, so they don’t care about the specifics. We are now in a fight for our lives and for the hearts and minds of Americans. As Charles said, what happens in Mississippi impacts Wisconsin. What happens in Wisconsin impacts Mississippi. So we have to begin to think through how we now create a critical mass that is able to fight for the hearts and minds of America. The question of abortion is one thing that is a big platform. The question of guns. But what is the infrastructure that begins to make the fight? That’s something we have to learn.

So, to me, there are two big things that we have to wrestle with. The first is how do millions of votes fight billions of dollars? Two, how do we now begin to define a reality that allows us to make sure that people who want to hurt us are never elected to political office? I don’t even think we have given ourselves permission to think at that level, but now we have to give ourselves permission, to think about being in charge and being in control. We should move from the protest mindset to the power mindset.

NU: One, I think it’s consistency, right? Not only do we need to win things, but then we need to defend those wins beyond one election cycle. And so this is how we govern, this is how we lead, this is how we get stuff done. Changing the culture of elections feels really important. Two, being real clear, the enemies of progress have always had more money than us. This ain’t new. We’ve never been able to compete dollar for dollar. But our power is in the ability to move people. It’s people power.

Yesterday [April 6, 2023], Tennessee expelled two newly elected state representatives, both named Justin, who were standing with young people and students after a school shooting in Nashville, Tennessee. There’s a child molester in the state legislature, a person convicted of domestic violence, and they don’t get expelled. [The extreme Republican leadership does] not care about norms, about the law of the land. We are headed into an era of power versus power. And our power does not come from money, it comes from the people.

CC: Absolutely. Charles, what are your thoughts on that?

CT: I got an eleven-year-old daughter, and when she was a little younger, she used to play games with me and she would create these rules. And every time I got close to winning, all of a sudden, a new rule came out or the rules would change. And I quickly learned, I was never gonna win playing by her rules ’cause they would just change. I oftentimes think we fall into the trap of trying to engage in a game, playing by house rules. The house always wins. We have to stop that.

We have to look at elections differently. We look at elections as if it’s the end-all-be-all. I would love a Southern Strategy where it is less about how can we win this election that’s coming up six months from now, than it’s about how can we win for people? And I’m not talking about no pie in the sky. I’m talking about a serious conversation where we’re making serious change for folks, because there are things that we control now that we take for granted.

Due to length, the following section was omitted in the print edition but is published here in full.

The second thing I would say is that we have to figure a way to truly engage folks in a hyper-local context. We were in Holmes County, Mississippi, working on Initiative 42. It was me and three other young Black men. We go up to a high school graduation in one of the most underfunded school districts in the state and all we wanted people to do was sign a petition to say: “Put this thing on a ballot to fully fund education.” We go up there, tuck in our t-shirts put on nice clothes, look all professional so that we won’t deter anybody. You know what ended up happening? No one wanted to sign our petition. And we’re thinking to ourselves: “Wait a minute, this is a all-Black high school. Clearly, it’s underfunded.” We got the permission of the superintendent to be here, talked to the principal, but nobody signed a petition. What ends up happening is Ms. Emma Butler comes up to us and she says, “Baby, what y’all doing?” Said, “Oh, we got this petition—” Before we can even finish it. “Oh yeah, I heard about that. Yeah, so what’s the issue?” I said, “Well, they won’t sign it.” “Oh.” “Jimmy, come here, Susie, da da da. Sign this petition.” So we restructured our strategy and our strategy became, we were the clipboard boys for Ms. Butler. So Ms. Butler would say, “Hey, come do this. Tell your mama come up here, da da da da.” We end up getting all these different signatures and these were people that we had just asked to sign this petition. But the difference was having Emma Butler.

And so I thought about what would it look like to be able to hire Emma Butler full-time as an organizer to do this work? But then also she has a strike team with her. Cause when we talk about engaging with folks, you can’t do it without local people who has that local context, who know to get deeply in these type of places. And I think we gotta have a serious conversation about how do we go into our areas with surgical precision and make these kind of things happen. Cause if we don’t, we may eventually elect a person, and it sounds great, but then what they’re able to do is not gonna connect to the folks that we really trying to reach. We have to build up and solidify that infrastructure up and down.

CC: Nsé worked in Georgia, Charles in Mississippi, and I worked in Alabama. One of the things Charles mentioned is the whole question of a Southern Strategy. And Charles also pointed out that what happens in the South impacts the United States, but the Democratic Party doesn’t believe that they can win in the South. The other problem is that most Black people live in the South. So the question then is, what kind of things do you think we should be doing until the country catches up with us on this issue? What should we be doing in terms of trying to make the South and the Southern Strategy important in terms of people understanding its impact on the nation?

NU: I’m gonna ask who is the Democratic Party? Because I would argue that their base is Black folks and that you’re not serious about winning nationwide if you are not serious about the South in this moment. That has been the case probably for the past, at least 40 years in the US. Before that you can be forgiven if you are a Democratic leader and did not sort of prioritize Black engagement, Black voter registration, Black investment as a strategy to win because they were able to win without Black folks. But now, there is no map that exists and there’s no path to victory for Democrats without centering Black folks. And I’m not talking about an increased investment. I’m talking about the centering of Black American voters. Full stop, period, point blank. And the easiest way for me to know whether or not I should take you seriously is whether or not you have any analysis about the South and how important it is for the future of American politics. I think that we all need to have that level of clarity as we are talking about what the Democratic Party is and what direction they will move in going forward.

I also think that to the extent that there are people who are willing and able to make interventions within the Republican party, that that needs to be a part of the strategy as well. I’m not saying I wanna hold that piece of the strategy. There are Black Republicans, right?

Three, this country is far too big for two political parties. And so I am actually encouraged and attracted and interested in doing more research with the Working Families Party and trying to understand them and the Green Party. And Libertarians. I don’t fully understand their ideology. I feel like they’re just diet Republicans or Republicans who are embarrassed by the racism of the GOP platform. What does it mean to have more parties? We’re a nation of 300 plus million people with two political parties. There are more people who live in California than who live in Canada. There’re more people who live in Texas than Canada. And Canada has five, six major parties that are represented in its parliament and on municipal levels. There needs to be serious conversation ’cause we talk about voters and we talk about candidates and we talk about elected officials all the time. I think that parties are an important piece of the infrastructure for organizers to be thinking about as a vehicle for us to build power and to contest for power.

CC: Charles?

CT: Yeah, three things. I’m glad you asked that question. The reality of it is people say they want the map to change, but they don’t want the consequence of that change. ‘Cause if you support the South, that means supporting Black and Brown people. That means supporting Black and Brown leadership and you have folks who are not ready for this. Now lemme be clear. You wanna win a White House, but if you don’t have the House and you don’t have the Senate, then it doesn’t mean as much. Imagine Biden’s first two years with the Senate that he has now. It’s a different reality for folks. There are people who would still be alive today that passed in them two years because of that. Or passed in the four years of Trump. Literally. We’re talking about lives. But people have to be honest about that point. You really gonna have to support Black and Brown folks. And I don’t think everybody is truly ready for that conversation.

And two was the amount of money that is spent on Black voters. I have been in campaign conversations where they said things like: “We’re gonna spend $25 for every white voter we engage and we’re gonna spend $2 on every Black voter.” And then at the end of the campaign, when they lose, they blame Black voters. So let me break this down. 350,000 Black people voted for you. 50,000 white people voted for you, but it’s a Black voter problem and you spend $2 for every vote for the 350,000 Black votes and $25 for those 50,000 white votes. I mean it is a number of conversations there. We gotta stop with that. We have to invest seriously in Black voters. But to Nsé’s point, it’s not just about the dollars, it’s about who has the power? Who has the ability to make a decision on how these things go?

And then the last thing I wanna do is talk about the parties. A lot of times we think about parties from this like national top down structure, but their function is bottom up and there’s engagement that doesn’t happen with our political parties because we just assume that whoever is in control is in control. Prime example of that. I was a delegate in 2016 for the national Democratic Party for Hillary Clinton. I was a delegate from Mississippi at large, and this was my first time engaging with the party. And so Derrick Johnson of the NAACP says: “Hey, you should try it.” And I’m so nervous, couldn’t sleep the night before cause I’m going to my precinct caucus and I’ve done a lot of work in Jackson and in Mississippi, but I hadn’t been intimate, particularly, in my precinct. I had a very active neighborhood association that was very political. So I know I’m gonna get there and these people done picked who gonna be the delegate years ago and they’re just gonna be looking at me like maybe next time son. I get to the location and the door is not open. I’m thinking I’m at the wrong place. Finally, my state representative comes up and he’s like: “Hey, they just told me this morning I had to be here.” We had 20 delegate slots and it ended up being four delegates from our precinct: my state rep, my ex-wife ’cause she just happened to drive with me and was in the car. And this gentleman just walked up and we was like: “Hey, you wanna sign this?” And so then we get to the county level, Same thing. Get to the congressional level, same thing. Get to the state level, same thing. I realized in that moment you could control the state party of Mississippi with about three months of organizing.

I’m saying that to say, if there was a concerted effort to take over the party, you could. And I’m not saying that you have to do it in a compromising spirit. You could literally say, uncompromising, this is who I am. I am the antithesis of what this party is now, but because I show up, I’m going to change it. And you know, that probably is the case for the majority of the states.

I agree with Nsé that we do have room for additional parties in this conversation, but I also want folks to know that what the values are and who’s at the table could easily change. I mean it could change with six months organizing. I think that that really is a metaphor for realizing what’s possible.

Talking about this conversation, the ability to define. Oftentimes we think about an ability to protest, but the problem sometimes I feel with protest is that you concede power to the thing you protesting ’cause you acknowledging it. That is, you are accepting how things are defined versus saying: “No, we’re gonna redefine this for ourselves.”

CC: Everything you’ve talked about and we’ve talked about is really important. But in terms of the concept of the Southern Strategy, as you look at the next two or three years, are there opportunities where we could actually not only think differently, but also act differently, and show people that these things can be different? Do you have any sense of whether that can happen the next two years or places that might happen?

NU: I am very bullish on Mississippi and I am actively participating in the delusion around Texas and the ability to flip Texas. Here’s the thing, it’s too big, it’s too important. But when those, what 38 I think electoral votes–somebody correct my math–come in the bag, it’s a wrap, right? The demographics are there already. Texas has its own money. It needs to be organized. That’s what is happening.2

I think Beto O’Rourke made a strong play. I think the difference between his first campaign and his second campaign, you can see the intervention that organizing made. He increased the level of sophistication, increased his racial justice analysis, his gender analysis, and he got closer than any Democrat has ever gotten in the past couple of decades in Texas. Those feel like real opportunities to me. Okay, let me nerd out for a second. I been doing some research and looking at a map. There are about 535 cities in the deep South in the eleven states of the former Confederacy that are majority Black or majority people of color where there’s never been a Black mayor and there’s never been a Black person or Latina elected to school board or city council. And those feel like opportunities. Is it President of the United States? No. But if I can get the first Black mayor in Willacoochee, Georgia elected, and then we use that to build the bench, to build the pipeline to contest for power everywhere, including rural Georgia, it’s going to happen.

CT: I sit on the board of Southern Poverty Law Center Action Fund and I think they’ve identified something like 6,000 hyperlocal races, where you have majority African-American, city, town, county, et cetera, but not a Black person in that seat. Echoing Nsé’s sentiment, these hyperlocal races matter and we can make some incredible wins.

Thinking about Beto O’Rourke, a good friend of both Nsé and I, Joe Kenny, tells a story all the time about him and Beto being best friends in Congress. And then when he ran for governor the first time, he would go to a place and they would say, “Oh, you the first Democrat to campaign here since LBJ.” And then the thing that Beto would say is, that was great, but he couldn’t say afterwards: “Oh, and by the way, this is the person that works on my campaign that’s in this county. If you wanna reach me or you wanna reach out to the campaign, you wanna organize with us, here’s who you contact.” It was: “I pop in, and I may get 20 more votes just ’cause folks are fascinated by the fact that I showed up.” But that 20 votes could have been multiplied to 2000, if you had local folks on the ground. And so we have to stop talking about states and even counties where we gotta focus on wining these two or three, because that’s what the maths say because they’re the most populated. There’s no county that’s not worth engaging in. It matters most in these places that are deeply rural. If you have folks and you can engage them, you can do some credible things.

But to answer your question, the governor’s race of Mississippi is exciting to me. Cause I think we have a real opportunity there with Brandon Presley. He is polling higher than the current governor. I’m not the biggest person on polls but I think that’s exciting. I think that this year we have an opportunity to increase the number of Black elected officials. Mississippi has more Black elected officials than any other state in the country. If we look at our last few election cycles, we increased that by 10% in 2019. From 2015 to 2019 we increased by 14%. I think we may increase by another 10% this year. This helps us getting to that moment in Mississippi where we are able to tip the scales. I think that we need to be engaging in redistricting conversations now, and throughout the South, because it is so gerrymandered. And it’s to the point now where I don’t know what we gonna do about it, but we gotta do something. ‘Cause that’s the other thing that is just really killing us is how these districts are shaped. But I think we have to begin that conversation now, seven years out. Really should have started right after, where we can really think and have these hard thinking conversations about what we can do versus reacting: “Oh, we’re gonna file a lawsuit because this is the district that they came up with.” And we know what the courts look like now and we know how that’s gonna go.3

CC: It seems to me that we’re talking about a New Southern Strategy. As we know, a thousand-mile march begins with the first step, right? What are the first steps here?

NU: You’re right. It’s the tip of the spear. We are at the vanguard. There is no cavalry coming. We are who is going to get it done. And I love that for us. I’m excited about the future. Here’s the other thing and this is how I wrap it up. I have been guilty over the past couple years of talking about the end of American democracy and that tax on democracy and people are trying to kill it. After having a little break and some time to pause and reflect and look back on our work, the truth of the matter is that’s a lie. We’ve never experienced actual democracy. Like, full participation, full democracy. And so the darkness that we are experiencing, it’s not dusk, it’s dawn, it’s the birthing, it’s three o’clock in the morning, right? And we are headed into what full participatory democracy could look like. And it’s not dark because the lights are being turned out, it’s dark because the lights are being turned on.

CC: For people like myself and the SNCC people, we know what it was like when it was dark. We know what it was like when it’s midnight. The work we did over the past sixty years got it to three o’clock in the morning. We now have to take it to five. That is what people need to understand. We are moving in a direction where the things we’re talking about now, we couldn’t even conceive of sixty years ago. And even the stuff that we did sixty years ago, a hundred years before that, we couldn’t think about that.

CT: I agree wholeheartedly. I feel that in my bones that it is happening, and I just think that we have to be a good steward of it. We have to move like it is three and not midnight. I think that we have to interrogate our tactics and our strategies, I think we have to think hard on these things, and I think that we gotta continue to fight. I’m excited about the future. I know we’re gonna take some licks before we get to dawn. But I’m excited, man. I think we got some good things happening, and I’m just happy to be in conversation with folks like you all and, you know, Mississippi is my life passion.

CC: The reality is that the two of you are probably some of the brightest minds around on these issues, and it is lived experience, not some theoretical stuff. And I think that if we are going to move forward, it has to be on your shoulders. I’m looking forward to continuing the communications and the conversation, but also more important than that, continuing the work. So I want to thank both of you. This has been really helpful, and I think that as we begin to think through the New Southern Strategy, I’m looking forward to working with both of you.

Emilye Crosby is professor of history at SUNY Geneseo. She is the author of A Little Taste of Freedom: The Black Freedom Struggle in Claiborne County, Mississippi, and editor of Civil Rights History from the Ground Up. She is a founding member of the Movement History Initiative, a collaboration which includes the SNCC Legacy Project, and is currently working on several projects related to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

NOTES

Emilye Crosby thanks Ethan Shaw for technical assistance, and Judy Richardson, Sarah Campbell, Nsé Ufot, Jennifer Lawson, and Kathleen Connelly for their help and feedback on various drafts.

- Justin Jones and Justin Pearson, two young Black Tennessee state legislators, were expelled by the legislature after they joined young protestors following a mass shooting in Nashville on March 27, 2023. Both legislators were later returned to the legislature. While both men were alleged to have violated procedures, the vote was an extreme step.

- Texas had 38 electoral votes in 2020 and has 40 in 2024.

- At the time of this conversation, Brandon Presley was a member of the Mississippi Public Service Commission and a Democratic candidate for governor, running on an anti-corruption platform. He lost the race and no longer serves on the Mississippi Public Service Commission.

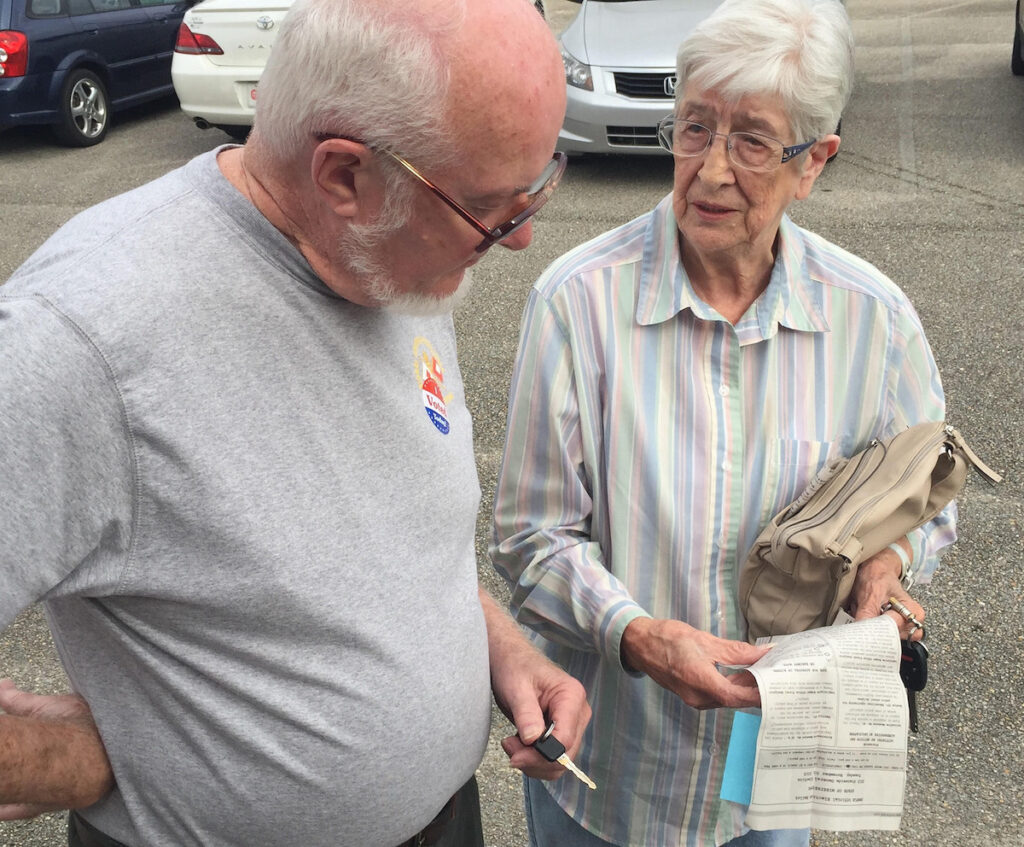

Header image: New Georgia Project canvasser Mardie Hill (left) speaks to a woman about the upcoming primary election, East Point, Georgia, May 23, 2022. Photo by Elijah Nouvelage/AFP via Getty Images.