As the Nasher Museum of Art celebrates its 20th anniversary, curators Marshall Price and Xuxa Rodríguez sit down to talk about two exhibitions now on view—Everything Now All At Once and Coming into Focus—and what it means to build a collection in the South today.

Marshall Price: What does the title Everything Now All At Once mean to you?

Xuxa Rodríguez: I was trying to find a way to talk about the contemporary moment and contemporary art in a way that would express the immediacy of it, and the immediacy being—the now is always happening even at this moment. This is the now, right? But look, it’s also gone now, because I just finished that sentence. So, Everything Now All At Once is the history that we think is in the past but actually includes things that we’re making at this moment. The contemporary moment itself is this living, breathing experience that we’re creating in the ethers as we move through it.

MP: I love how you organized [the show]. Can you just say a few words about that?

XR: We came upon this idea of a mix tape, like greatest hits. A mix tape is a really idiosyncratic product that you make, or gift, essentially, where you’re thinking of making it for a person, but you’re not talking to that person about what they want. You’re just collecting all these songs and thinking, “Oh, they’re going to like it. I want them to feel these ways.” And you’re putting it together with highs and lows on these flourishes. It’s kind of like the process of creating a permanent collection, where the institution is imagining who the audience is.

I mean, we have, to an extent, an idea of who our audience is, but we’re imagining who will look at these works, what could they get out of it educationally, emotionally, spiritually, even. Some people talk about having transcendent experiences when experiencing art, but we can’t guess what that person’s going to do when they see it. So, it’s kind of organized around the sense of making a mix tape for our community. And you can see that even in [the exhibition] design by Joel Johnson—beautiful hand drawings and lettering that give the sense of a physical mix tape for everyone walking through the show. Let me ask you a similar question.

Can you give me a quick overview of the show you curated with Ellen Raimond?

MP: Coming into Focus is a broad swath of the museum’s photography collection. It covers nearly the entire history of photography from its inception around the 1840s all the way up to today. So, it’s a very good representation of our holdings. And Coming into Focus means a way in which we can continue to build this collection. Obviously this is not the end of collecting for the institution, but really the beginning in many ways.

XR: There’s this moment when you walk [into the show] where there’s this high contrast between two works. To me, as someone walking through, it kind of encompassed a quick dialogue that’s running through the show.

MP: When a visitor enters [the exhibition], they encounter the very first photograph that the Nasher’s predecessor, the Duke Museum of Art, acquired in the early 1970s—a photograph by John Menapace. The second work the visitor encounters is the second work that the Duke University Museum of Art purchased, a large Cindy Sherman, twenty years later. But it really signals two things, I think. [Those purchases were] prescient in that they looked ahead not only to our acquisition of artists from the area with the work by John Menapace [of North Carolina] but also our concentration on contemporary art in the last twenty years.

XR: Yeah, I think it’s really fascinating. The exhibition starts with that Menapace photo in the seventies because that’s kind of the period that photography became accessible via technological advances. You had the Kodak Instamatic and people could go and process their own film versus sending plates off or hand processing their own plates for printing. And much like contemporary art, photography at that time was not necessarily popular within institutions . . . because of these romances of what does a great collection of art mean? Only recently have we been like, “Oh, the present is great.” What does it mean for the museum to mark its twentieth anniversary with shows like these?

MP: Well, I think in some way it’s about taking stock of the last twenty, but at the same time, and more importantly, it’s really about what the next chapter is for the institution and looking ahead. I think these shows are sort of preludes to what comes next.

So now let me ask you, what do you think the exhibitions say about the role of artists working in or from the South today?

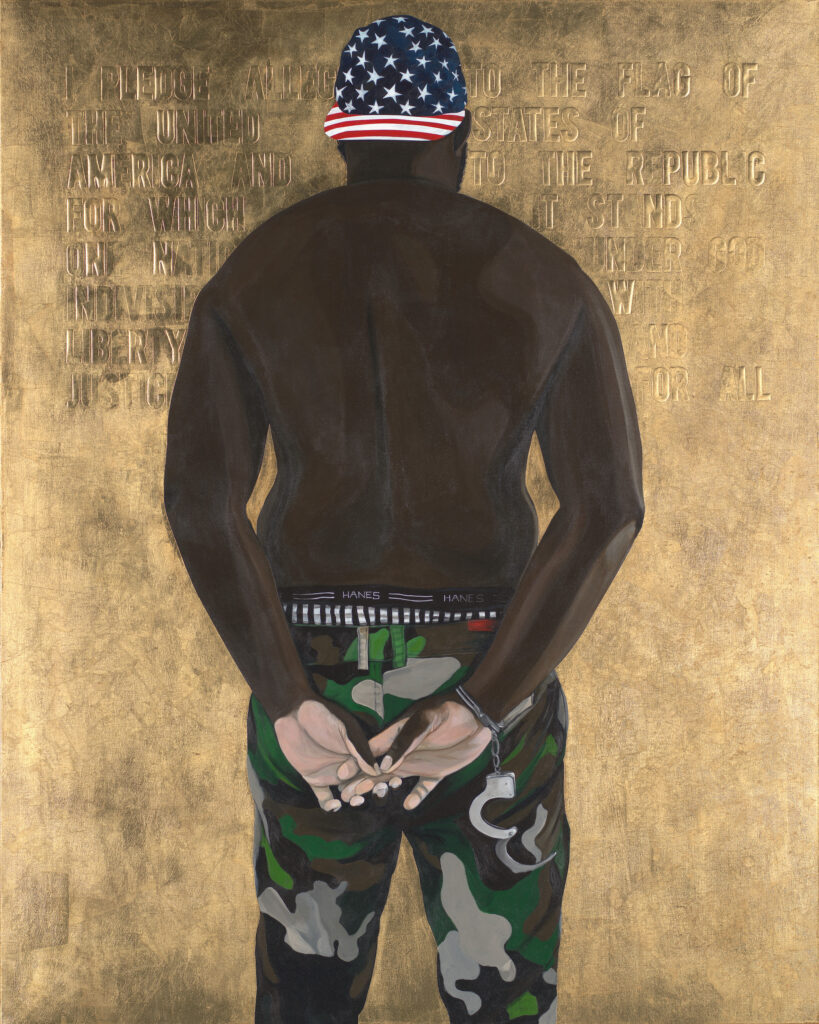

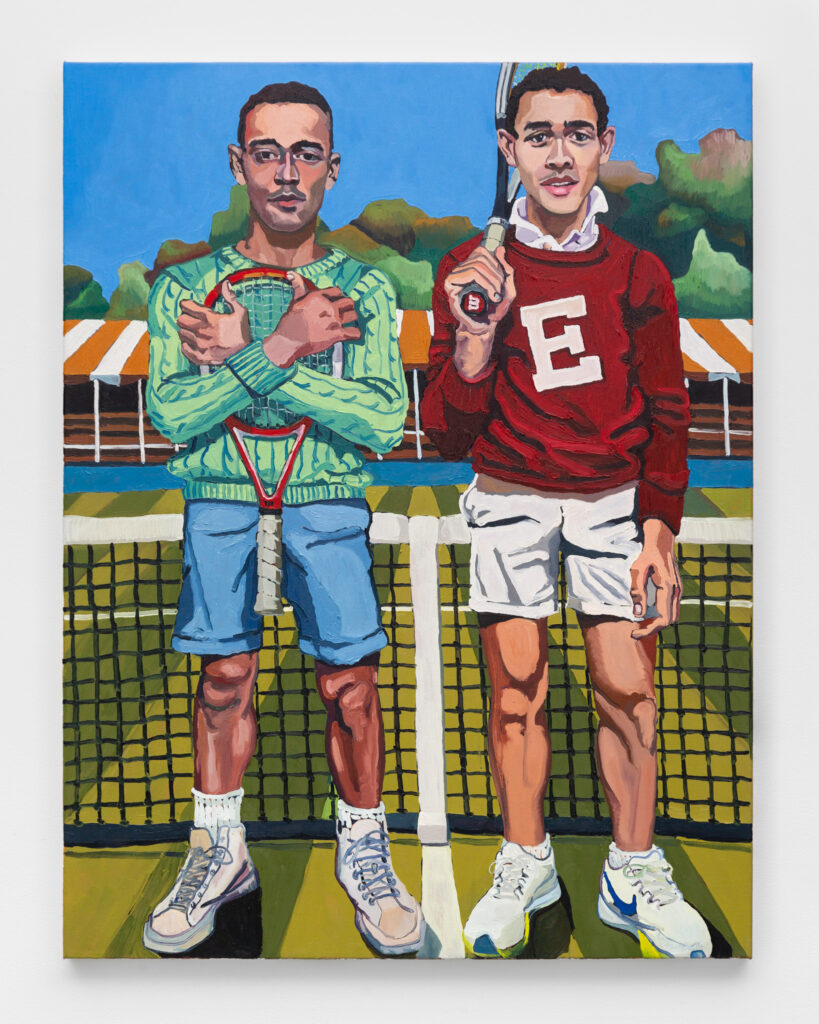

XR: I can hear Clarence Heyward, one of the artists featured in Everything Now All At Once. He’s based just outside of Raleigh and he just opened his own show at Ella West Gallery here in Downtown Durham about artists from the South. [At the opening], he quoted André 3000 when he said, “The South got something to say.” The South does have something to say, and it’s always had something to say. But the region doesn’t necessarily come into the imaginary when one thinks about the art world geographically, right? It’s kind of like off to the side. It’s not part of those four major points [New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Dallas], at least when you think about where the major galleries are, which is not to say we don’t have major galleries.

But the exhibitions highlight ways in which southern artists are working together and talking to each other. There’s this beautiful connection between a Beverly McIver painting and a Nicolas Coleman painting in Everything Now All At Once. You can see that maybe they’ve never had a direct conversation, but at least in visual languages of painting and how they think about painting, even just how they apply it, they’re obviously moving in the same circles or hanging out in the same spaces where they’re exchanging processes and mark-making histories.

These exhibitions are also doing the work to put those artists in the region in dialogue with national and international movements, and national and international artists. I’m thinking about how in Coming into Focus there is a very quiet moment with the William Eggleston [photograph] next to other still lifes. If you blink, you miss it. But that quiet little moment by an artist from the South of this color photo of tomatoes on the kitchen sink is a landmark moment in the history of photography, because Eggleston really made color photography something. At the time when photography came out, it was like it wasn’t fine art if it wasn’t black and white. But Eggleston really popularized color photography and showed how beautiful and how lush it could be.

MP: Well, that’s a good segue to ask if you feel like the Nasher is helping redefine what southern art can mean? You alluded to this by saying how we’re putting artists from the region in dialogue with national and even international artists.

XR: Yeah, when I think of the collection of the Nasher and I think of “southern art,” I think it really highlights to me a geographic location, not necessarily a style or an aesthetic. Yes, there have been styles and aesthetics that artists from this region have created, but that’s not to say that southern art, as a category, is a specific mode or sense of being. It is about the dialogue here between these artists living in this region and what’s going on, not just geographically—as we have more experiences like Hurricane Helene and the loss of the community, such as the arts community in Asheville that’s now rebuilding—but also, what it means to live in an area that is so historically fraught, thinking of the Civil War. Or thinking too of the coast itself with all the erosion that’s gone on, especially as you get further south into the Gulf and the Atlantic Caribbean Coast at the southern points, and how those areas have been ravaged with climate change and the climate crisis. And also migration between those points and beyond. How are the artists responding and what are their lived experiences and how do they find community and speak to each other and speak to this experience in dialogue with folks around the world who are having similar experiences?

MP: Yeah, I think your show does that beautifully because it really reflects what the institutional collecting trends have been over the last twenty years by highlighting artists of color, women artists, those artists who have been historically marginalized.

XR: I’m also thinking of the Hassan Hajjaj image [in Coming into Focus] of the women motorcyclists. And then the frame made with Pepsi cans and how that kind of talks about the Global South. It makes us rethink how folks that we have historically thought of as minoritized within the US, because of the history of the US, are actually part of a global majority.

And making that dialogue clear through the way that the contemporary and modern collections have been growing into this global contemporary dialogue—looking at artists across these time periods are not necessarily just working in the regions that they are based in, but they’re also part of this global exchange.

Are there specific works or artists in the shows that feel particularly meaningful in that context?

MP: One work that really sticks out in terms of a representation of our past collecting practices is the Ming Smith self-portrait from the early 1970s—it’s a photograph that she took of herself in a mirror as a young woman of color in a moment in this country when there was incredible exclusion of groups of people of color. It also speaks to a kind of subjectivity, I think, that is so intimate and personal.

XR: So this is in the wake of the civil rights movements, the Equal Rights Amendment, and women and femmes gaining financial independence.

MP: Yeah, and I mean, you’re really good at understanding a broader social context out of which these works were made, and out of which these images come. It just brings so much more depth to them, as you just illustrated with Ming’s work.

XR: I think, too, it says a lot about the Nasher’s collecting practices as a whole since 2005—deeply looking at artists in their historical and lived contexts and how their experiences and stories can speak to our guests, who are coming through the door and engaging with the works and see themselves reflected within it, see their experiences, find community within the exhibition spaces.

MP: Is there a piece in these shows that surprised you, challenged you, or stuck with you long after seeing it?

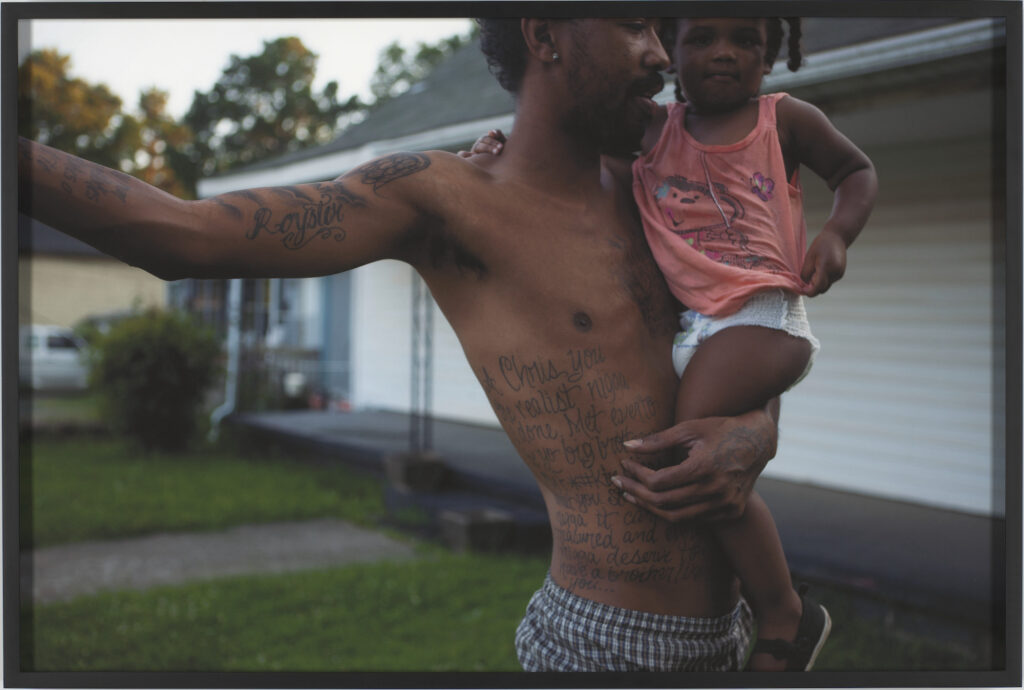

XR: It’s Titus Brooks Heagins’s portrait, “Kevin and Desnique,” from the series, “Durham Stories, Not Hell, But You Can See It From Here.” I keep coming back to it [and] thinking how quickly Titus is able to establish rapport and intimacy with folks that he may or may not have a relationship with.

He’s walking through the neighborhood, he’s coming across folks, and if you look at this photo, you can see he’s maybe standing all of five feet away from them. And the moment that he’s captured is a father or guardian figure sweeping his arm out, and the little girl is tugging down her shirt and makes this beautiful shape, so it’s almost like they’re dancing in space. This was just like a slice of life moment that Titus captured on film, and it is an image that sticks with me that says a lot about his virtuosity as an artist, as a photographer, being able to be present enough.

MP: The decisive moment.

XR: The decisive moment. And Titus knows when the decisive moment is happening. I’ll ask you the same thing. Is there a piece in the show that surprised you, challenged you or stuck with you long after seeing it?

MP: I would say in Coming into Focus the work that has stuck with me since I first saw it is MJ Sharpe’s “Outside Amarillo,” which was shot late at night outside Amarillo, Texas, and depicts a grain silo next to a small low-slung building in what is otherwise a sort of deserted landscape. It’s eerie and intimate, and the coloration is saturated. It looks otherworldly. Formally, it’s this incredibly beautiful image, and in the show it hangs near an Edward Weston and an Ansel Adams, and to go back to what we were saying before of putting artists from the area—MJ is based here in Durham, originally from Tennessee—in dialogue with more national or international artists is such a gratifying thing and creates these really interesting dialogues.

If you had to describe these shows in one word or phrase, what would it be?

XR: It’s a birthday party on a pretty epic scale. It’s the whole building. How about you?

MP: It feels like the museum is finally entering into adulthood at twenty years.

XR: Well, that is kind of the age folks are just about to finish college. Are we going off to grad school now? Are we going straight into the workforce? What would our job be if the museum were a person, or what would we be doing?

MP: Something in social justice.

XR: And trying to do international diplomatic work.

MP: Well, we both can look forward to a bright future, I think.

Header image: William Eggleston, Untitled from the series The Democratic Forest, c. 1983–1986. Pigment print, edition 4/5, 20¾ × 29⅛ (52.7 × 74 cm). Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC. Gift of Jennifer McCracken New (T’90, L’94) and Jason G. New (L’94), in honor of Kristine Stiles. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Image courtesy of David Zwirner, New York, NY / London, UK.

Marshall N. Price is the Chief Curator and Nancy A. Nasher and David J. Haemisegger Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and serves as adjunct faculty in the university’s Department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies. He received a Ph.D. in Art History from the Graduate Center, City University of New York and has held positions at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and the National Academy Museum, New York.

Xuxa Rodríguez, PhD, is the Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher Curator of Contemporary Art at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. She earned her doctorate in art history from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her expertise ranges across modern and contemporary Latinx and Latin American art, African diasporic art, feminist and queer art, transnational artists, and time-based media, with strengths in digital art, performance, and video. Previously, she was the Associate Curator for Contemporary Art at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and the Momentary.