Annabelle (18), Mekenzie (18), and Tanielma (17) stand at the edge of Island Road in Terrebonne Parish, the part of Louisiana’s coast that remains barely above the sea, watching as two excavators move dirt to build berms that might protect the land. When a storm blows from the west, or the east, the wind pushes water onto the road, sometimes making it impassable. Mekenzie is from here, “down the bayou,” which is sinking nearly faster than anywhere else on earth. She points to the open water: “That used to be land. My grandparents remember herds of cows and wild horses.” Tanielma, who lives in Baton Rouge, and Annabelle, who lives in Lafayette, stare at the blue-gray waves and try to imagine cows. These types of observations about climate change are increasingly commonplace. Less often considered, though, is how this knowledge alters our sense of who we are and what we can do.

I met these three young women, who did not previously know each other, when I invited them to learn with me and my filmmaking team, and their respective communities. My idea was to use filmmaking as a classroom, and to try to develop a documentary practice for the climate crisis through experiential learning and observation. One day, for example, we filmed on the Atchafalaya River Basin with Dean Wilson, the Basin Keeper, who cares for the swamp. Guiding us through the second-largest river swamp in the world, Dean described how the trees here once stood two hundred feet tall, draped in thick Spanish moss. “Today, all that remains are [the] hollow trees because they were not useful as timber,” he said. He described how “in 1700, in Louisiana, there were somewhere between 8 to 10 million acres of cypress forests. But throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, the trees were chopped down to build plantations, homes, and the railroad. The moss was picked for mattresses, automobiles, and housing insulation.” As Annabelle, Mekenzie, and Tanielma floated by the remaining hollow old-growth trees (the inspiration for the film’s title), they began to imagine Louisiana’s past and, by extension, Louisiana’s future. The one that they will experience and help to shape.

Hollow Tree follows the three young women as they come of age in their sinking home-place. Annabelle is white, with Cajun roots, Tanielma Black and Angolan, and Mekenzie is a member of the United Houma Nation. Together, their different perspectives tell a story about the climate crisis in Louisiana, which, as they come to see it, specifically endangers Black and Indigenous lives. We watch as they learn about what has been lost in extracted landscapes and discover how we arrived at our present planetary crisis by considering the stumps, spillways, and towering levee walls of their home landscapes. “We learned a lot from each other just from talking,” said Mekenzie. “We saw how all of our narratives are a piece of the story,” Tanielma agreed.1

At the start of filming, Annabelle, Mekenzie, and Tanielma took the engineering of the Mississippi River for granted. They didn’t realize that the river created Southeast Louisiana, building the state’s coast as it switched course. My favorite account of this is by John McPhee, who describes the river jumping “within an arc about two hundred miles wide, like a pianist playing with one hand.” To Annabelle, Mekenzie, and Tanielma, however, the river was docile, stuck on a course already determined, an image of inevitability about our environment and the way we relate to it, and, in turn, relate to one another. Over the course of filmmaking, they followed their curiosity about the places they live. We read together, studied maps, and I prepared them to interview family and community members. The film brought them into conversation with people of different generations, races, socio-economic backgrounds, and forms of expertise, including scholars, scientists, crawfishermen, engineers, and community activists. Onscreen, the young women, and, in turn, viewers, gain new knowledge but also experience the awkwardness of not knowing, of looking for the right words, and of accepting that we might be wrong.

From this place of discomfort, a new conversation takes form. “For me in school, it was always, you know, you open up a textbook, you take notes, take a test. Boom. I’m done,” said Mekenzie. “I was never gonna use this again. I mean, I’ve learned in school . . . about all of these explorers, like ‘Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492.’ See, it rhymed! Stuff like that stuck.” “Yeah,” Tanielma nodded, “there was a sort of detachment when we’re learning at school. Learning through the documentary was very different because we were engaged. It wasn’t just ‘climate change is happening.’ It’s happening in our backyards, like right next to us, and so it affects us personally. And that’s something that’s missing at school. We just learned these facts, and nobody stopped to talk about how it affected your life and everything about you.”

My filmmaking practice evolved out of my own alternative education. Reading Myles Horton, the founder of Highlander Folk School, John Dewey, Paolo Freire, bell hooks, and Audre Lorde, and watching educational children’s shows like Voyage of the Mimiand 3-2-1 Contact, has inspired me to observe more deeply, to seek teachers in many places, and, as a white director, to engage with the process of having become white. This has meant an ongoing effort, largely through reading, to undo the socialization that denies our country’s histories of Indigenous dispossession and slavery, and the aspiration for control embodied by the river levees. In her book Teaching to Transgress: Education as a Practice of Freedom, author and educator bell hooks writes about teaching her students to be critical thinkers, and about “thinking as an Action.” She believes that it’s only with a radical openness, wherein neither teacher nor student is too attached to or protective of their viewpoints, that critical thinking can occur. Similarly, Freire asserts that education can only be liberatory when everyone claims knowledge as a field in which we all labor. Taking these lessons, in every step of our filmmaking process, we are all learning together—producers Chachi Hauser and Monique Walton, our filmmaking team, collaborators, and me.2

In the film’s research phase, Chachi and I spent time in communities along the Mississippi River—in Dulac, Bourg, Isle de Jean Charles, Henderson—asking people what they noticed changing in their environments. Crawfisherman Roy Blanchard told us how the Atchafalaya River once had “a blue clay bottom,” that the water was so clear that they could drink from it. Chris Brunet told us about the sheer land mass of Isle de Jean Charles when he was a child. “It wasn’t like this,” he said, referring to the pockmarked patchwork of land and water that now characterizes its scenery. Shirrell Parfait-Dardar, Chief of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, told us how the systemic drilling of oil canals caused saltwater to intrude on the coastal wetlands, where many in the tribe live, killing the cypresses, now called “gray ghosts.” “Chief trees,” Parfait-Dardar pointed out, were oak trees planted atop traditional native burial mounds. Because they were elevated several feet by the mounds, they escaped the saltwater; as a result, they were the only living oak trees, and often the only living trees, left in this area. While the remains of the dead protect these oaks for now, at the rate the sea is rising, they will be gone in a decade.

In the car, driving back to New Orleans, Chachi reflected on her newfound understanding of these trees. It made her remember being a child in New York City, thinking “a patch of dirt with a tree growing out of it was simply a spot where concrete wasn’t. I realized,” she continued, “how strange it was for a young person to take for granted the extent of human control over the environment. Since these decisions seem to have already been made for us and have been exercised to such a great magnitude, another way of relating to our environment can seem unimaginable. Understanding how much our country has been built on values of control and exploitation,” Chachi said, “shifted my sense of responsibility.” This is precisely what our filmmaking process is about: learning to expand attention and care.

Prior to production, I spent more than a year visiting the locations where we would later film, often with Chachi. Chachi’s producing role included recording conversations, taking notes, reading, and delving into archives with me at the Historic New Orleans Collection or Louisiana State University’s library. We’d then decide which texts or maps might be useful to share with Annabelle, Mekenzie, and Tanielma. The goal was to guide them in an inquiry process where the documentary form constituted a path to new understandings. We’d submerge ourselves in the physical landscape, too, swimming in the Atchafalaya and wondering if feeling sediment in the water would shape a young person’s understanding of how land was made. How could we accelerate a learning process? And how does this learning become cinematic, so that audiences could also experience it?

Our research trips became “casting” trips where we’d interview young people about their experiences of climate change in different parts of the state. I met Tanielma, Mekenzie, and Annabelle through friends of friends, and they all struck me as exceptionally curious and open to the adventures of filmmaking. They were also generous with their stories and their questions. Early on, Tanielma told me: “One day, it was raining a lot, my school bus came to pick me up, we made one turn, and the water was up to the glass doors. My mom was driving home and her car got flooded. We didn’t have a car for two years . . . I want to know why it flooded so much in my neighborhood.” Tanielma’s city, Baton Rouge, is along the Mississippi River, northwest of New Orleans, where, in 1909, Standard Oil built one of the largest oil refineries in the world. The tacit and toxic relationship between oil and more frequent flooding is maybe best reflected in the image of a jumbo shrimp embracing an oil rig, advertising Louisiana’s annual Shrimp and Petroleum Festival.

We learned during filmmaking that when an oil rig pulls oil out of the ground, it leaves behind a cavity that causes the land above it to sink. The widening canals, originally dug for pipelines, further contribute to saltwater intrusion. Since 1932, the combination of dredging and drilling for oil and gas and leveeing the Mississippi River has resulted in the disappearance of a Gulf Coast land mass 1.2 times larger than the state of Rhode Island. Mekenzie lives on this fraying coastline, at the bottom of Louisiana’s proverbial boot, where she has gone fishing with her family all her life. Over her short lifespan, she has noticed the waterways changing: “They’re really wide now. The land isn’t the land anymore. Everything is changing. People’s whole attitudes are changing. They just don’t have a care for anyone but themselves. They just see water and just the pointlessness of water. And we see, like, fish in there. That’s a sense of living for us.” Annabelle is from Lafayette, west of Baton Rouge, heavily populated by people who work in the oil and gas industries. “In my town,” she says, “climate change is a myth.” Through the filmmaking process, the young women began to recognize the false cultural narratives that undergird a concerted denial campaign.3

Annabelle, Tanielma, and Mekenzie learn that before settler colonials arrived in Louisiana and “shackled” the Mississippi River, building levees with enslaved labor, New Orleans was known as “Bulbancha,” the land of many tongues. It was a lush swamp inhabited by Indigenous peoples that flooded seasonally. In our filmmaking process, we would look for evidence of the river’s “remembering,” in Toni Morrison’s words—the natural movement in the batture, the flat bank between the levee and the river, which is sometimes grassy and sometimes flooded, or the round hills, Indigenous burial mounds, in the middle of Louisiana State University’s campus—to “reconstruct the world that these remains” implied. Together, we read about how settler colonials attempted to turn a wet, dynamic, shifting landscape into stable, dry agricultural plantations. During research and production, producer Monique Walton shared the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project (which “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative”), and we discussed it with Annabelle, Tanielma, and Mekenzie. We visited the Whitney Plantation, one of the only plantations in the South that tells its story through the perspective of the enslaved, and the Woodland Plantation, where the largest slave revolt in North America began in 1811. This archeological aspect of my filmmaking process is a kind of “wake work,” a term suggested by theorist Christina Sharpe, who uses a ship’s wake as a metaphor for living in the unfinished project of emancipation.4

We documented moments where Annabelle, Tanielma, or Mekenzie asked the generation that came before about their experiences with segregation or land dispossession. LEAN (Louisiana Environmental Action Network) helped Tanielma, for example, set up a visit to St. James Parish to interview activist Genevieve “Eve” Miller, whose grandparents were emancipated from slavery and bought a plot of land where a refinery now stands. Today, the eighty-five-mile stretch of river between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, once dense with plantations, is colloquially called “Cancer Alley” or “Death Alley” and experiences the highest cancer risk in the United States. “If the trees are looking like this,” Eve tells Tanielma, pointing to leaves covered in brown spots, “what do you think the air is doing to our health?” Eve described to Tanielma how people of color and the land have both been subjugated since the earliest days of European settlement. In our collective research and effort in making Hollow Tree, we found that the questions of the climate crisis—whose lives are in dangerous proximity to toxic oil refineries and whose are not, and whose land is being protected and whose is not—are legacies of slavery and removal and dispossession of Indigenous peoples. “Solving it” is a relational, not a technical, matter. In facilitating conversations across generations, class, and race, the film, both as a process and a product, models why the coming together of these perspectives is necessary to gain a full picture of how we arrived at this moment.

In this concept of filmmaking as a classroom, we seek to redistribute narrative power to the young women in the film via a process of co-learning. This is, in part, an effort to remedy exploitative practices in art and politics, those that have resulted, for instance, in the climate crisis. Extractive storytelling—storytelling that doesn’t respect the humanity or needs of the community whose story is being told—and extraction in the form of mining, logging, and oil drilling coevolved, the former validating and reinforcing the latter. This relationship is starkly visible in Louisiana Story, the 1948 film commissioned by Standard Oil. Louisiana Story follows the adventures of a young Cajun boy and his pet racoon as his grandfather allows an oil company, represented by friendly white men, to drill behind the house. Robert Flaherty, the celebrated director of the first commercially successful documentary film, Nanook of the North (1922), represented Cajuns in Louisiana Story as primitive and romantically entwined with nature. While the film is scripted and the narrative is linear, it is shot in a documentary style to feel “real.” Long montages depict the film’s protagonist paddling his pirogue through majestic cypresses and dodging alligators. Like all propaganda, however, the film is, in the words of Vietnamese documentarian, writer, and scholar Trinh T. Minh-ha, “a mere vehicle for ideas.” Every image, sound, or silence is in service of a clear message: oil drilling is a benign and inevitable process. When the drilling is complete, the company leaves behind a pristine environment and a wealthy Cajun family. Seventy years later, however, Mekenzie, Tanielma, and Annabelle witness its malignant impacts.5

In one scene in Hollow Tree, the young women gather on an abandoned oil rig in coastal Louisiana, where sinking land is visible in all directions. Unlike in Louisiana Story, where the Cajun boy sees the oil rigs in the bucolic bayous of his home as beacons of progress and prosperity, the young women in Hollow Tree question why we tend to ignore the oil infrastructure in our landscape. Offscreen, Mekenzie, Tanielma, and Annabelle reflect on oil’s role in land loss as a continuation of the dispossession Indigenous peoples suffered. Hollow Tree’s editing aspires to follow their emotions but refuses to package images, sounds, and silences into a specific message. Instead, the film is open to interpretation, like a poem. Mekenzie, Tanielma, and Annabelle’s rejection of the oil industry’s narrative shapes their quest to know themselves.

As young women, in particular, Annabelle, Mekenzie, and Tanielma have not been encouraged to trust their feelings. Through co-learning, visiting sites, and participating in the film, they put language to what they felt—about family members who had no choice but to work in the oil industry and who therefore participated in the destruction of their home; about a person in a position of power who was denying the effects of climate change; or about the fear of rain that recurring hurricanes had instilled in them. In the words of Audre Lorde, “For as we begin to recognize our deepest feelings, we begin to give up, of necessity, being satisfied with suffering and self-negation, and with the numbness which so often seems like their only alternative in our society.” Identifying and exploring their feelings empowered the young women to validate their instincts and give voice to their concerns. As Tanielma put it, “It feels like society is always drowning out my voice and emotions. While filming, Annabelle, Mekenzie, and I were free to speak openly and express our raw reactions.”

Tanielma Da Costa exploring the oil refineries across from the Bonnet Carre Spillway in Norco, Louisiana.

Tanielma Da Costa exploring the oil refineries across from the Bonnet Carre Spillway in Norco, Louisiana.

Annabelle, Tanielma, and Mekenzie learn that land loss, or subsidence, like the failure of the levees during Hurricane Katrina, is not the result of what the historian Andy Horowitz refers to as “external attacks, ahistorical acts of God, blows from without.” Just as people built the levees that broke, people caused the land to sink, and recognizing the consequences of human action on the landscape can invoke a feeling of irrevocable loss. Scholar Stephanie LeManger describes this loss as “a geological complement to melancholia when [it] is understood rather simply, as a grieving that has no foreseeable end.” Climate denial inhibits mourning, which hinders a way forward. However, a feeling of melancholy, a recognition of loss, is an incitement for Annabelle, Mekenzie, and Tanielma to act, as when Tanielma pointedly challenged the Army Corps of Engineers when she was told that “global warming has no effect on our river systems.”6

In the process of untangling oil myths and facts, the young women come to see their own stories in the landscape. Indeed, Mekenzie, who grew up on the vanishing wetlands with her Houma community, stated that “the land being taken away is part of myself being taken away.” Upon recognizing how humans accelerated coastal land loss, Tanielma, who moved with her family from Angola to Louisiana as a child, observed how Louisiana’s land attrition is comparable to land theft in war. Annabelle, whose family has lived in Louisiana for generations, visited the Whitney Plantation and learned for the first time the narratives of the enslaved. Previously, she’d only experienced plantations as wedding venues. In the context of filmmaking as a classroom, Annabelle expressed that she “felt okay to say, ‘I don’t really know what this is’ and ‘I don’t understand this.’ From that place,” she continued, “I could comprehend things more fully.” These young women demonstrate how listening to people who are different from them, absorbing their perspectives, and sharing their own opinions allows them to arrive not at a foregone conclusion, “the straightened river,” but in a conversation that transforms its participants and invites the possibility of change.

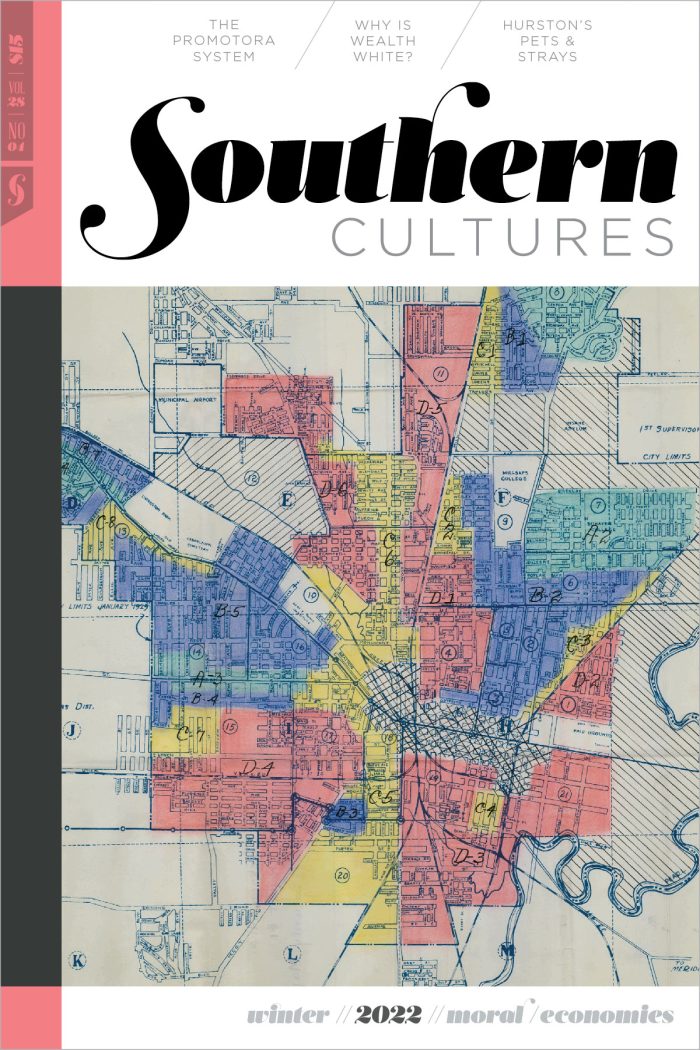

This essay was first published in the Moral/Economies issue (vol. 28, no. 4: Winter 2022).

Kira Akerman is an educator and a documentary filmmaker who lives in New Orleans. Her debut feature documentary, Hollow Tree, has been supported by the Sundance Institute and the International Documentary Association, among others. She often collaborates with Ripple Effect, a New Orleans environmental education start-up dedicated to K-12 climate change education.Header image: Annabelle Pavy, Tanielma Da Costa, and Mekenzie Fanguy learning about Woodland Plantation, where the slave rebellion of 1811 began, in LaPlace, Louisiana. All photographs courtesy of the author, from her film Hollow Tree.

NOTES

The author extends special thanks to Andy Horowitz, Isidore Bethel, Meryl O’Connor, Chachi Hauser, and Jasper Frank for their thoughts on early drafts.

- Once the filmmaking process is complete, Annabelle, Mekenzie, and Tanielma will accompany the film at screenings and speak on its behalf. This is a model I developed for my earlier short film, Station 15 (PBS), which follows high school student Chasity Hunter as she learns about New Orleans’s pump station system and finds language to challenge its threats to her community. Representing the short film in public—at the Global Climate Action Summit, for example, and at the New Orleans City Council meeting—was an extension of Chasity’s journey in the film. In an interview on New Orleans public radio, she said that she wished that more young people “felt confidence to try and pursue learning about science or doing something with their own knowledge.”

- bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress (New York: Routledge, 1994); Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 1970), 1–15.

- Brady R. Couvillion, John A. Barras, Gregory D. Steyer, et al., “Land Area Change in Coastal Louisiana from 1932 to 2010,” U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3164, scale 1:265,000, 12 p. pamphlet, 2011, accessed August 10, 2022, https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/blog/SIM3164_Pamphlet.pdf.

- The Army Corps of Engineers boasted of “harnessing it, regularizing it, and shackling it”; Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, 2nd ed., ed. William Zinsser (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1995), 83–102.

- Nancy Chen, “‘Speaking Nearby’: A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-Ha,” Visual Anthropology Review 8, no. 1 (Spring 1992).

- Andy Horowitz, Katrina, A History: 1915–2015 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 3; Stephanie LeMenager, Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 102.