In 1971, as Black Panther Robert Hillary King Wilkerson later wrote, “The mood in the streets had caught up with the men in prisons.” That same year, Robert King, Albert Woodfox, and Herman Wallace formed the first official incarcerated chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP) in the largest maximum-security penitentiary in the United States, Louisiana State Penitentiary, colloquially known as “Angola Prison.” King attributed the growing attitudes of defiance at Angola to the ideology of the BPP. Although the men who became known as the Angola Three learned the principal tenets of the BPP while confined at different prisons, they joined the party and came together at Angola to advocate for universal healthcare, education, and an end to police brutality, priorities of the Black Panther Party. They recognized the importance of food to mobilize others and compel prison officials to meet their demands. Hunger strikes, resource pooling, and sabotage of food production built solidarity among prisoners who proceeded to resist jailers’ goal of total control over imprisoned people. Through such tactics, they participated in a broader movement that prioritized the health, autonomy, and bodily integrity of incarcerated people.1

The food activism of the Angola Three—the refusal, sabotage, and use of food production and consumption to contest social and political conditions—fits within a Black radical tradition that has historically mobilized food consumption, production, and distribution for collective political action. Put differently, Black freedom fighters have long transformed themselves and their conditions via food. As scholar Analena Hope Hassberg argues, “Food is a powerful medium to shape the world that we want in place of the one we are critiquing.” Both incarcerated and nonincarcerated people have harnessed the power of food for social change. Civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer’s insight that “food is used as a weapon” made plain the connection between malnutrition and poverty and provided an avenue for groups such as the BPP and food justice organizations inspired by them to critique capitalism and engage in political education while mitigating hunger.2

While the state made use of insufficient and unsafe food practices as a weapon against the incarcerated, prisoners also used food as a weapon. Exercising bodily autonomy through food choice or food refusal has proven a concrete way for prisoners to alter their conditions. Demands twenty-five and twenty-six of the Attica Liberation Front exclusively focused on improving food safety, quality, and choice. Mealtimes and eating venues have historically served as spaces to forge connections, strengthen relations, and oppose racial segregation. Notably, cafeterias served as crucial sites for desegregation campaigns by imprisoned radical conscientious objectors during the Second World War.3

The Angola Three encouraged dissent at a place where food and agriculture were sites of struggle. Prison administrators demanded the cultivation of sugar by prisoners and poor quality food and malnutrition served, and continue to serve, as part of the punishment that accompanies incarceration. BPP members organized around food because Angola prison administrators used food production and consumption as punishment. When prisoners in Angola lodged their complaints about the food served in the kitchen to legal organizations, they reported “rotten food” and food with flies served even after prisoners made guards aware of these unsafe food practices. Across other correctional facilities in Louisiana, incarcerated people reported poor food and going to bed hungry, stating, “People in here are undernourish[ed]. No way anyone of the guard’s in here are going to tell me we get over one thousand calorie’s [sic] a day.” Prison employees forced prisoners to cook and serve this insufficient and unsanitary food to other prisoners against a backdrop of rising canteen (prison store) prices and food insecurity in the streets.4

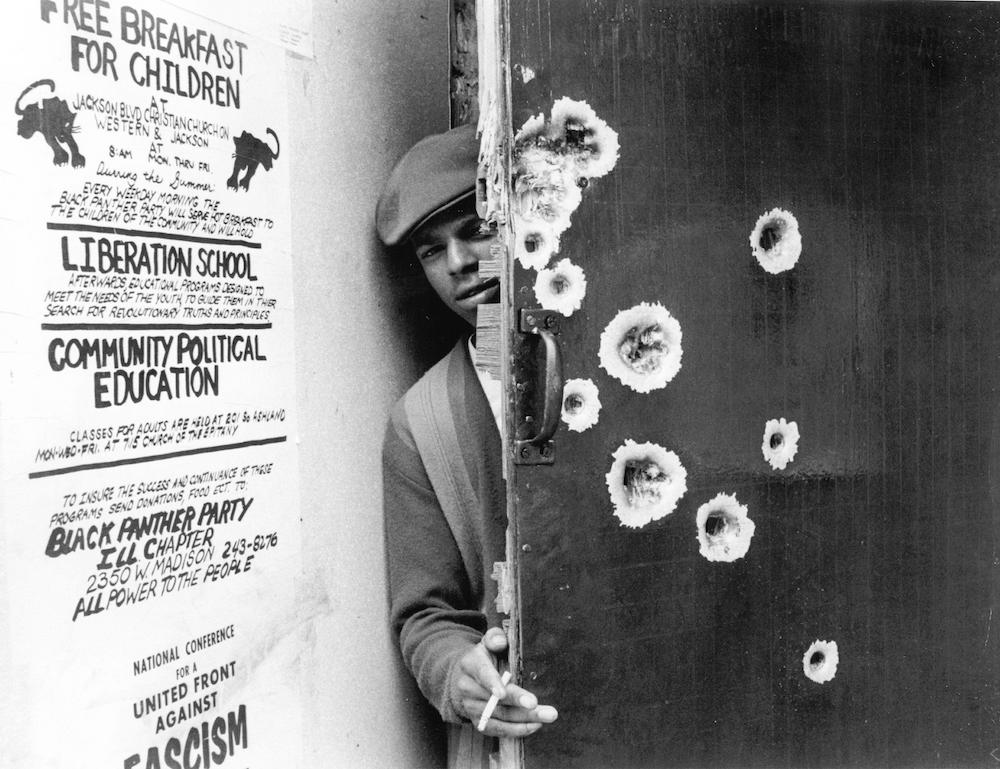

Black Panther Party members worked to ensure that their organizing was not stalled by the walls and cages of prisons and jails. Incarcerated members of the party and of Black liberation organizations such as the Nation of Islam disseminated liberatory ideologies throughout the late sixties and early seventies. Through support from outside strugglers, many incarcerated people were exposed to political education and joined liberation movements. The BPP recognized the importance of food and of supporting imprisoned people through survival programs. In addition to its well-known Free Breakfast for Children Program, the BPP ran the Free Commissary for Prisoners Program and the Free Bussing to Prisons Program for families and loved ones of incarcerated people to visit their kin. The party provided these survival programs to sustain and feed those in need and thought of food as a resource for “survival pending revolution.” This meant that the Panther’s survival programs were not meant to be solutions to hunger, poverty, and lack of healthcare. Rather, the survival programs ameliorated material conditions for people while allowing the party to organize around the causes of these issues.5

By the time the Angola Three formed a chapter of the Black Panther Party at Angola Prison in 1971, American political life was in a state of tumult and prisons were in crisis. Across the United States, oppressed people were demanding their rights through rebellions and social movements. As Black Panther Party cofounder Huey P. Newton wrote in 1970, “As long as the people live by the ideas of freedom and dignity there will be no prison which can hold our movement down.” In 1970, imprisoned people at the Manhattan Detention Complex, known as the Tombs, staged an uprising. On August 21, 1971, correctional officers assassinated Black freedom fighter George Jackson, which escalated resistance from others in the Black Freedom Movement. Prisoners in Attica responded to the assassination with a silent fast, and erupted in rebellion less than three weeks later. The Attica Prison Uprising inspired incarcerated people around the country, and internationally, to continue their resistance. These years between 1968 and 1972, called the “Prison Rebellion Years” by formerly incarcerated poet Raul Salinas, evidenced that social upheaval during this time period was not contained by state responses of prisons and policing.6

Incarcerated Black Panther Party members believed that, through prison organizing, they struggled alongside people who were taking to the streets to demand change. Woodfox remembered, “Being in prison we were at the forefront of social struggle and it was our responsibility to respond to the issues.” The Angola Panthers initiated concrete actions to educate and protect incarcerated people such as, but not limited to, using recreational time to have educational meetings under the guise of playing sports, giving reading lessons, and establishing protection for those vulnerable to the prison’s sexual slave trade of incarcerated people.7

Members of the Black Panther Party exercised power and influence inside and outside of prisons. C. Murray Henderson, warden of Louisiana State Penitentiary in 1972, shared King’s and Woodfox’s views of social upheaval reaching prisons. About Black militancy, Henderson said it was “something that is happening all over the country. You’re getting more militants in prison all the time and you have people who consider themselves political prisoners.” While prisoners were broadening their ideas of who political prisoners were, law enforcement in the streets was targeting and incarcerating members of militant groups. Prisoners nationwide recognized their roles in movements like the Black Panther Party, and these groups acknowledged their incarcerated members.8

The unrest happening around the country did not merely coincide with but was actively connected through figures such as the Angola Three before they ever met. During Woodfox’s incarceration with Black Panther Party members in the Manhattan House of Detention, he first heard members of the Party share their teachings with people in the jail. Robert King joined the party while incarcerated in the Orleans Parish Prison. King first felt “kinship” to the party after witnessing, on a television, a shootout between party members and police near the Desire Housing Project in New Orleans. It was there, too, where Malik Rahim, member of the New Orleans Black Panther Party and lifelong organizer, exposed Herman Wallace to the party by giving Wallace the shoes off his feet when he noticed Wallace had inadequate footwear. In keeping with prison resistance tactics, Woodfox and King had participated in food activism at these institutions. Woodfox discussed grievances, on behalf of his floor, with prison officials during the 1970 New York City Jail Rebellion, which incarcerated people launched after their grievances (including a demand for “edible food”) went unanswered by jail administrators. Similarly, King engaged in a hunger strike at the Orleans Parish Prison. Their experiences participating in food activism at separate institutions influenced their actions at Angola, showing them that food as a site for resistance was a viable way to unify people and secure tangible gains.9

By repurposing food as an entryway to discussing politics and prison conditions, the Angola Three followed the blueprint of the Black Panther Party whereby “food served a double purpose, providing sustenance but also functioning as an organizing tool.” Woodfox understood that access to better food was a common desire among prisoners. In turn, he utilized that desire as an opportunity to discuss the links between food and related systems of oppression, such as poverty and hunger. This was an avenue to discuss the teachings of the Black Panther Party and build solidarity between incarcerated people at Angola. Throughout his incarceration, Woodfox used food and sites of food production to encourage collective resistance. During his time working in the kitchen, he encouraged workers to petition the warden to reduce their sixteen-hour workdays. Woodfox told his fellow prisoners that the long work hours in the kitchen, paid at mere cents an hour, were “slave labor.” He also made conscious efforts to disrupt racial segregation by discussing with white kitchen workers the mistreatment of all prisoners at Angola.10

Woodfox’s interracial outreach efforts were not unique. On the streets, the Black Panther Party made alliance with other racial and ethnic groups, including those represented in the United Farm Workers. In prisons, groups such as the Nation of Islam (NOI) worked with Latinx and white prisoners to demand change. Through methods such as hunger strikes, legal action, and sit-ins, NOI members challenged poor food and beatings of prisoners by correctional officers, and secured important legal victories that expanded constitutional rights for prisoners.11

When Woodfox was not engaging in his assigned duties, he made a commitment to furthering the anticapitalist teachings of the Panthers that he had learned while incarcerated at the Tombs. From the party, “I learned that the best way to reach each man on the yard was at his own level of consciousness. I started to talk a lot about the food and how bad it was.” Long before Woodfox’s incarceration, however, prisoners at Angola had voiced opposition to the food quality there, describing it as “bad—hardly fit for a dog.” Food was an ongoing site of contestation at Angola, one that could serve as an effective site for unifying people based on a common grievance. One way that the Angola Three unified prisoners was by staging hunger strikes.12

The Angola Three initiated a forty-five-day hunger strike that forced the prison administrators to structurally alter cells. “A hunger strike is probably the most effective form of protest in prison, but they’re the most brutal because you’re attacking yourself,” Woodfox recalled. Prisoners sought to have food slots cut into the cell bars to improve hygienic conditions and alleviate the physical and emotional degradation of receiving their food trays below dirty cell bars. The strike did not end until prison officials guaranteed that they would cut slots into cell bars. Woodfox and King initiated the strike because “they’re sliding the food across the dirt to us like we’re dogs.” The installation of food slots meant that prisoners would no longer have to consume food contaminated with debris and bacteria. Yet, this change did not come to Closed Cell Restriction for eighteen months.13

During this time, prisoners in that area continued to eat their food in a modified fashion, imagining solutions to maintain their standard of eating. Some designed slings in their cell bars to hold their food trays while they ate. Others held the tray with one hand and fed themselves with the other. In the end, the strike led to slots cut into cells throughout all of the prison, and the entire population benefited from the sacrifices of the strikers. Their practice of modifying eating practices even while waiting for the guaranteed changes demonstrates how even under constant surveillance and control by carceral regimes, incarcerated people assert their autonomy in everyday life.14

After the strike, prison guards and imprisoned workers at Angola delivered food to prisoners through specialized food slots. Though they put their health on the line during the hunger strike, food was not only significant for nutritional purposes but building community among incarcerated people. Prisoners on other Closed Cell Restriction (CCR) tiers, an extended lockdown area of the prison with nine-by-six-foot cells where the Angola Three were confined, signed a letter supporting the strike. Everyone in CCR agreed to participate. In consulting others before initiating a hunger strike and turning it into collective resistance, prisoners increased the severity and urgency of the strike.15

This hunger strike at Angola was so successful that it inadvertently resulted in the prison offering foods (such as fried chicken) that were otherwise deemed contraband to motivate strikers to eat. Wilbert Rideau, former editor of the prison-based newspaper the Angolite, detailed in his memoir that food was the most common form of contraband. Precisely because food was vital to material being and because securing the food prisoners desired gave them some measure of control over their lives, food served as a critical site of prisoners’ resistance. Where unseasoned spinach and boiled potatoes were common, prisoners with money could secure contraband such as bacon and pastries, which may have been brought into the prison by employees with access to outside food. The Department of Corrections used sought-after foods to entice prisoners to end the forty-five-day hunger strike in which Woodfox participated.16

During this strike, the most determined strikers did not eat for forty-five days. Woodfox himself skipped the first meal after the strike, breakfast, because he did not enjoy eating oatmeal. The Department of Corrections countered by going as far as offering what under usual circumstances was considered an illicit market food, fried chicken, to hunger strikers. This was a common practice that prison officials used to encourage people to eat. Prison officials also attempted, unsuccessfully, to weaken the strikers by informing them when a person agreed to eat. These tactics were unsuccessful in terminating the strike. While other tiers came off the strike before prison officials met their demand, tier A (where Woodfox and King resided) and tier D (where Wallace lived) continued to strike. The lengthier strike on the A and D tiers could be attributed to the strong influence of the Angola Three, who made conscious efforts to inspire and politicize those in their proximity.17

This hunger strike built on a long tradition of strikes at other prisons and detention centers. At Milan Prison, a federal prison in Michigan, Muslim prisoners staged a hunger strike that resulted in food that fit their religious requirements—notably no pork and a separate dining section for halal food. In a Connecticut jail, Black Panther Party cofounder Bobby Seale participated in a strike to protest the isolation of “left radicals” such as himself. Seale recalled, “The food was good. Wasn’t the food we were arguing about. I was arguing about the fact that you’re isolating people.” Food was used to protest dietary conditions and political repression, and to push for more dignified living conditions. Hunger strikes challenged more than just food quality; they built collective power to contest a variety of repressive state practices.18

Members of the Angola Three recognized the power of food to gratify, nourish, and connect the incarcerated in a unified struggle. The collective experience of hunger striking deepened solidarity among prisoners and allowed for a practice of discussion that bred emotional and mental resilience through their hunger. During their hunger strike, Woodfox details, “We sat on the floor by the bars and talked a lot. It sounds crazy but we talked about food. We described our favorite dishes in detail to one another. … We talked about what would be our first meal when we got out of prison.” Strikers replicated the emotional aspects of eating by recalling joyous memories together, cultivating hope and excitement over their culinary experiences after release. When imagining his dream home while imprisoned, Herman Wallace, with the assistance of artist Jackie Sumell, constructed a home where people could cook.19

Even though regulations did not permit cooking in cells, Woodfox recalled that “for years it was tolerated, especially if we gave some of the food to the freemen [guards] on duty.” During his time working in the kitchen in 1962, Robert King perfected a recipe for pralines, a traditional New Orleans treat, with the help of another prisoner, “Cap Pistol,” who was well regarded inside and outside the prison for his culinary skills. King became known for the confections that he cooked in his cell—even prison guards purchased King’s pralines. The sugar and butter came from other prisoners, the pecans were contraband, and King cooked the confection on a makeshift stove in his cell. He continued making these candies during his time in solitary confinement and sold them after his release, calling them “Freelines.” While King’s confections were at first served for the purpose of satisfying people at the prison, after release he continued to produce these candies for funds, further propelling the political work and advocacy of the Angola Three.20

Robert King’s sale of Freeline candies to support his comrades is embedded within a larger tradition of Black radicalism. Since before the abolition of slavery, Black people used their agricultural and culinary skills to raise money to sustain their own communities. Historically, Black-owned restaurants have served as venues to strategize and fundraise for social change. For example, Thomas Downing, known as the Oyster King of New York, supported the Underground Railroad with funds from his restaurant. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Georgia Gilmore, known to “[fix] the best grub in Alabama,” sold pies and cakes to sustain the boycott. She regularly prepared meals for civil rights leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and for civil rights marchers. In Atlanta, Paschal’s restaurant donated food to and bailed out protestors, while also serving as a venue for organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to plan their next moves. In New Orleans, chef and civil rights activist Leah Chase of Dooky Chase’s restaurant is remembered by the city and her family for her restaurant’s role as a venue for people in the Civil Right Movement, both Black and white, to convene.21

Similar to how the Angola Three promoted communal actions through hunger strikes, they recognized the power of pooling resources to purchase goods, including food. This practice prioritized collective comfort and safety, allowing members of the group without individual funds to access supplies. By purchasing items from the canteen for the entire group, prisoners enhanced a sense of obligation to one another. In doing so, they reinforced safety and disincentivized theft without relying on penal officials to achieve this aim.22

Wallace and Woodfox began combining resources by asking other men whose visitors supported them financially to begin pooling their money for the benefit of the tier. The practice was simple; anyone who wanted an item such as candy, chips, tobacco, or slippers could request it. If someone violated the rules the collective had agreed upon, they would not receive their item. The Angola Three mobilized their brethren to live more comfortably without depending on the state to institute new programs and policies.23

The pooling of resources was one example of how incarcerated people cultivated trust to address their own needs and reduce interpersonal conflicts. Notably, Black prisoners at other institutions also purchased and prepared food collectively. At Clinton Correctional Facility, a state prison in New York, Muslim prisoners created their own space for cooking meals because the prison did not offer halal cooking spaces. They used this makeshift kitchen for education and religious activities before, as had happened to the Angola Three, the state put them in solitary confinement. Prison administrators viewed resource pooling as a threat because it bred unity and fostered the politicization of prisoners.24

The Angola Three’s resource pooling was significant because it allowed prisoners vulnerable to violence and those with families fighting poverty to access goods and higher-quality food from the canteen. Prisoners protested these circumstances while connecting their struggle to those of their family members in the streets, relating in The Angolite, “The families of prisoners have too many survival priorities which exceed the prisoners [sic] stomach needs for tuna fish, sa[rd]ines, and soft drinks.” This made clear that families of prisoners as well as prisoners themselves struggled to meet their basic needs, and navigated food insecurity. Prior to their incarceration, King and Wallace faced hunger and turned to shoplifting and robbery to provide for their families. Whether incarcerated or not, people in poverty could seek relief from groups such as the Black Panther Party through community food drives, by connecting to the BPP free commissary for prisoners program or through resource pooling.25

The Angola Three were keenly aware of how the state utilized the labor of those incarcerated at Angola for food production. Woodfox recalls that during his time at Angola, the division of labor reinforced the racist order of the prison. Officials responsible for work assignments gave white prisoners priority for administrative jobs and indoor work assignments on prison grounds such as the sugar mill. On the other hand, Black prisoners were most often sent to harvest sugarcane in the plantation’s fields. Former prisoner Wilbert Rideau reported to the warden at the time, C. Murray Henderson, that he was unable to fulfill his work assignment as a clerk in the prison canning factory due to racism. White prisoners, following the tradition of white preferential treatment, were more often assigned to clerk and craftsperson work. There were no Black employees as incarcerated clerks or free Black employees as late as 1970, and the first free Black employees fought to both secure and keep their jobs.26

Reminiscent of production under slavery, sugarcane harvest work was physically intensive. Sugar processing required long hours seven days a week, and cane season was regarded as the toughest time of year for prisoners. Once cane grinding started, it went on twenty-four hours a day without interruption. Guards pushed field workers to harvest sugarcane in groups meant to yield large harvests. The fastest workers went first. In turn, guards forced others to keep up with the fastest pace or risk a write-up for a work offense. What made the harvest so difficult, in Woodfox’s opinion, was the speed expected of the workers. Precisely because the extraordinary labor demanded by the state during sugarcane season inflicted exertion on those assigned to the field, fieldhands devised strategies to ameliorate the harsh conditions.27

Incarcerated people knew that sugar processing, from cutting sugarcane to working at the sugar mill, presented many opportunities for defiance. Field laborers at Angola dreaded harvesting sugarcane so much that bodily mutilation was a common protest tactic. In February of 1951, protestors at Angola garnered political attention when multiple men, dubbed the “Heel String Gang,” purposely cut their Achilles tendons. The plantation’s only nurse, who performed surgery on the Heel String Gang, testified that she was sure that the prison’s widespread mistreatment, notably during sugarcane harvest time, was the motivation for their self-inflicted injuries. Many forms of self-harm never drew significant media attention. For example, prisoners turned to one another to injure themselves, offering payment to break hands, arms, and ankles to avoid work. As the prison demanded labor and accumulated sugarcane, incarcerated people created their own social economy where “old-timers” made “good money” breaking others’ bones to incapacitate them for the season.28

Besides these extreme methods of sabotage, prisoners found less conspicuous ways to resist. The Angola Three encouraged fellow prisoners to work slower and harvest less. Woodfox details in his memoir, “It was this macho thing where the guys would deliberately work at a fast pace to show off how masculine they were, and we’d explain to them that all they’re going to do is take you to another field.” By encouraging fellow prisoners to decelerate their work pace, the Panthers weakened the Department of Corrections’s ability to maximize production. Work slowdowns on larger scales happened in May 1977 when seven or eight hundred field-workers staged a slowdown. As a result, they were punished with confinement to Camp J, a cell block of the prison “akin to a dungeon.” The Angola Three also encouraged incarcerated people working inside facilities to put pressure on the administration, a tactic that the state would use against them.29

Because the Angola Three subverted prison order, officials were quick to pin violent outbreaks on the group. In 1972, a guard, Brent Miller, was murdered on the same day that kitchen workers were striking, refusing to work until they spoke to the warden. C. Murray Henderson, warden of Angola at the time, claimed that the Angola Three were behind the work stoppage and the murder. He argued that the work stoppage was a distraction used to carry out the killing. Woodfox claimed he was innocent. He detailed in his memoir that he had been talking to the kitchen workers about their rights for weeks but was neither present at the scene of the murder nor did he directly organize this strike. Regardless, prison management retaliated against the Angola Three.30

The political identity of the Angola Three influenced their treatment after Miller’s death. Wilbert Rideau and Billy Sinclair later recalled, “The Miller killing provided an official license for indiscriminate terror and violence against black inmates, especially those suspected of being militant.” The state and prison officials associated prisoner militancy with violence against correctional officers and planned prisoner disruption of prison order. Former Warden Burl Cain admitted that Woodfox’s involvement with the Black Panther Party was reason for sending him to closed cell restriction (colloquially referred to as solitary confinement) for over forty years. Regarding Woodfox, Cain stated in 2008, “I still know that he is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison, because he would organize the young new inmates. I would have me all kinds of problems, more than I could stand.”31

Because the values of the Black Panther Party inspired the Angola Three and other believers to act in ways that opposed the penal order, efforts to suppress this ideology were conscious decisions on behalf of penal officials. After his release, Woodfox confirmed that he “had many opportunities to get out of solitary confinement, but the price was too great. Prison officials wanted me to renounce my affiliation with the Black Panther Party, and they wanted me to give up my social and political philosophy, and just be a good little boy.” Even after more than forty years of solitary confinement, Woodfox never renounced his political ties to the BPP.32

The understandings and practices of Robert King, Herman Wallace, and Albert Woodfox are a powerful portrayal of how incarcerated individuals harness the power of food to advance toward their visions of freedom. Situated on a prison plantation, the Angola Three integrated food into their own use of the teachings of the Black Panther Party. They did this by organizing hunger strikes, pooling resources, and encouraging the sabotage of food production both in the fields and in the kitchen. Their strategies proved an effective method for increasing trust and communal bonds between prisoners. They accompanied their food activism with tactics such as literacy and political education. The Angola Three and their comrades realized that collective action was more effective than individual resistance, and that their individual actions could inspire collective action.33

The Black Power Movement, and comparable related social and political movements inside and outside of prisons, particularly on the streets, motivated the Angola Three and their comrades to resist as they did. Linkages between incarcerated resisters and worldwide revolutionary movements in the last third of the twentieth century were also an important mechanism for motivating prisoners. However, the resistance of the Angola Three notably lasted far longer than the Black Panther Party, despite both suffering intense state repression. The Angola Three continued to advocate for their freedom even after they were, as Woodfox described, “forgotten by the party, by political organization, by people involved in the struggle”; they “had no choice but to continue [their] struggle on [their] own.” Woodfox and Wallace noted that only their bodies were imprisoned; their minds were free. As BPP veteran, former political prisoner, and supporter of the Angola Three Safiya Bukhari remarked about the party ideology, “We had to learn and internalize it for the day when the offices would no longer be open to us … when we would be on our own without other Panthers so that we could carry out the tasks of the revolution.” The Angola Three did just that during and after the decades that they spent in solitary confinement.34

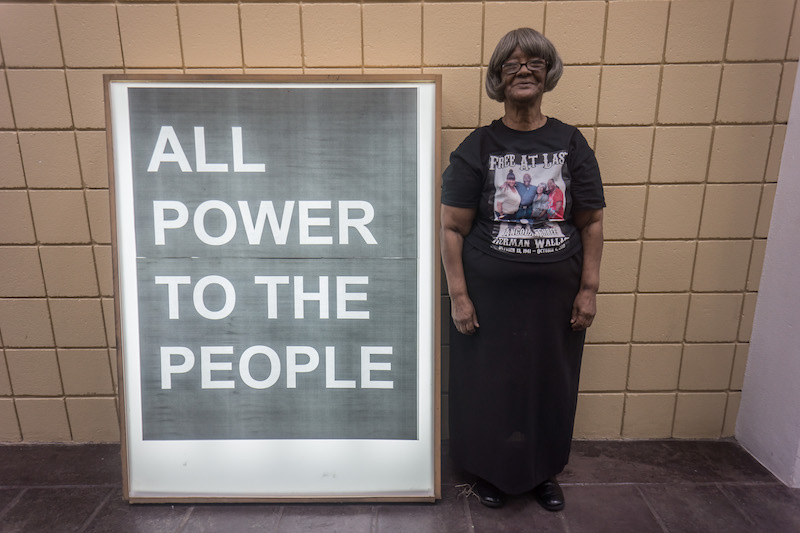

After decades of legal, social, and political struggle, the Angola Three left prison with the support of the International Coalition to Free the Angola Three. Louisiana corrections released Robert King in 2001, Herman Wallace in 2013, and Albert Woodfox in 2016. Wallace passed away on October 4, 2013, three days after his release due to terminal cancer. While he did not receive a death sentence in a court of law, there exists no doubt that the poor living conditions, lack of medical care, and lack of nutrition in prison contributed to the decline of his health and ultimately his death. Robert King and Albert Woodfox continued their advocacy after their release from prison through public engagements and memoirs, emphasizing Wallace’s memory.35

Now able to share his treats with the outside world, King continued cooking and selling Freelines. Woodfox’s list of activities to do when released included eating home cooking and having dinner with his family. In 2019, Woodfox delivered the keynote speech at the Making and Unmaking Mass Incarceration conference, a convening organized by Garrett Felber that brought together students, scholars, activists, and community members to advance the future of prison abolition. Wallace, Woodfox, and King remain central figures in the struggle to abolish solitary confinement. The lives and labor of the Angola Three embody the sentiment that “everything worthwhile is done with others.”36

This essay first appeared in the Abolitionist South Issue (vol. 27, no. 4: Fall 2021).

Gabrielle Corona graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 2021 with a BA in United States history. At Berkeley, she was a Mellon Mays undergraduate fellow and a member of the Underground Scholars Initiative. Her research interests are critical prison studies, social movements, and African American history.NOTES

- The author is grateful to the Southern Cultures editorial team, anonymous reviewers, and especially the guest editors. This article was made possible by the support of Mellon Mays at the University of California, Berkeley, with the mentorship of Professor Waldo E. Martin Jr. The author also wishes to thank Michael Banerjee for reading drafts and providing comments. Finally, thank you to Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace, and Robert King for sharing their determination with the world. Patrick Alexander and Albert Woodfox, “Opening Keynote” (conversation, Making and Unmaking Mass Incarceration conference, Oxford, MS, December 4, 2019), https://mumiconference.com/transcripts/; Robert Hillary King, From the Bottom of the Heap: The Autobiography of Black Panther Robert Hillary King (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012), 13, 171, 19; Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, “Organized Inside and Out: The Angola Special Civics Project and the Crisis of Mass Incarceration,” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 15, no. 3 (July–September 2013): 199–217; Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 55; Albert Woodfox, Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement. My Story of Transformation and Hope, ed. Leslie George (New York: Grove, 2019), 83, 164, 91. Robert Hillary King Wilkerson’s legal name is Robert Hillary King, though he also uses the surname Wilkerson at times.

- Rebecca Tuuri, “But If You Have a Pig in Your Backyard … Nobody Can Push You Around: Black Self-Help and Community Survival, 1967–1975,” in Strategic Sisterhood: The National Council of Negro Women in the Black Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 128–148; Analena Hope Hassberg, “Nurturing the Revolution: The Black Panther Party and the Early Seeds of the Food Justice Movement,” in Black Food Matters: Racial Justice in the Wake of Food Justice, ed. Hanna Garth and Ashanté M. Reese (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 98, 84; Mary E. Potorti, “Food for Freedom: The Black Freedom Struggle and the Politics of Food” (PhD diss., Boston University, 2015), 13.

- Anthony Ryan Hatch, “Billions Served: Prison Food Regimes, Nutritional Punishment, and Gastronomical Resistance,” in Captivating Technology: Race, Carceral Technoscience, and Liberatory Imagination in Everyday Life, ed. Ruha Benjamin (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 78; “The Attica Liberation Faction Manifesto of Demands and Anti-Depression Platform (1971),” Race & Class 53, no. 2 (October 2011): 28–35; Scott H. Bennett, “‘Free American Political Prisoners’: Pacifist Activism and Civil Liberties, 1945–48,” Journal of Peace Research 40, no. 4 (2003): 413–433.

- Billy J. Daigle, complaint to American Civil Liberties Union of New Orleans, March 10, 1988, box 14, collection 436, Amistad Research Center, New Orleans, Louisiana; Patricia Leigh Brown, “The ‘Hidden Punishment’ of Prison Food,” New York Times, March 2, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/02/opinion/prison-food-farming-health.html; Hatch, “Billions Served,” 67; Tyrone Wells, complaint to American Civil Liberties Union of New Orleans, April 26, [1970s?], box 14, collection 436, Amistad Research Center; Henry Reed, Angola Prison Questionnaire, [1971?], box 72, collection 117, Thomas C. Dent Papers, Amistad Research Center; Charles Harrell, Angola Prison Questionnaire, 1971, box 72, collection 117, Thomas C. Dent Papers, Amistad Research Center.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 63; Orisanmi Burton, “Organized Disorder: The New York City Jail Rebellion of 1970,” Black Scholar 48, no. 4 (October 2018): 28–42; Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr., eds., Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016), 191; Raj Patel, “Survival Pending Revolution: What the Black Panthers Can Teach the US Food Movement,” Food First Backgrounder 18, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 1–3, https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/BK18_2-2012_Summer_Survival_Pending_Revolution.pdf.

- Huey P. Newton, The Genius of Huey P. Newton, ed. Eldridge Cleaver (San Francisco: Black Panther Party, 1970,) https://archive.lib.msu.edu/DMC/AmRad/geniushueynewton.pdf; Burton, “Organized Disorder”; Dan Berger, Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 93; Woodfox, Solitary, 89–90; Robert T. Chase, We Are Not Slaves: State Violence, Coerced Labor, and Prisoners’ Rights in Postwar America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 242–244; Heather Ann Thompson, “Which Side Are You On?,” chap. 28 in Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (New York: Pantheon Press, 2016); Orisanmi Burton, “The Minimum Demands,” New York History 102, no. 1 (Summer 2021): 13–16; Dan Berger and Toussaint Losier, “Revolution: The Prison Rebellion Years, 1968–1972,” chap. 3 in Rethinking the American Prison Movement, American Social and Political Movements of the Twentieth Century (New York: Routledge, 2018). For information about hunger strikes outside of the United States, see Banu Bargu, Starve and Immolate: The Politics of Human Weapons (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014); and Thomas Hennessey, Hunger Strike: Margaret Thatcher’s Battle with the IRA, 1980–1981 (Kildare, Ireland: Irish Academic Press, 2014).

- Burton, “Organized Disorder”; Alexander and Woodfox, “Opening Keynote”; Woodfox, Solitary, 82, 164, 82, 34, 25–28, 163; Albert Woodfox, “Albert Woodfox on Solitary Confinement, the Black Panthers, and Fighting ‘the System,’” Channel 4 News, July 10, 2019, YouTube video, 51:29, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mrjSEx5TCQ.

- “Angola 30 Militants in Maximum Security,” Daily World, April 19, 1972; Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 16.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 66, 196, 75; King, Bottom of the Heap, 158, 163; Joshua B. Guild and Jeff Whetstone, “Malik Rahim’s Black Radical Environmentalism,” Southern Cultures 27, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 40–65; Burton, “Organized Disorder.”

- Patel, “Survival Pending Revolution”; Chase, We Are Not Slaves, 247; Woodfox, Solitary, 88.

- Hassberg, “Nurturing the Revolution,” 89; Garrett Felber, Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 81–82.

- Burton, “Organized Disorder”; Woodfox, Solitary, 86; “Angola Women Prisoners Called Disturbing Factor,” Monroe News-Star, March 13, 1951; “Convict Farmers of Louisiana. How Prisoners of the Angola State Plantation Are Worked — Wonderful Revolution in the Convict System — Louisiana Leads the List in Humanity and Practical Benefits Both to Prisoners and the State — A Description of Angola Farm and the Work There by a Staff Representative — The Board of Control Has Accomplished Marvelous Results. History and Description of the Angola State Prison Farms,” July 14, 1901, Louisiana Digital Library, p. 8, https://louisianadigitallibrary.org/islandora/object/state-lwp%3A7673; “Strike of Convicts at Angola Farm Led to Whipping,” Daily Signal, November 5, 1915.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 157.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 158; King, Bottom of the Heap, 118.

- Alexander and Woodfox, “Opening Keynote”; Woodfox, Solitary, 157.

- Potorti, “Food for Freedom,” 209; Wilbert Rideau, In the Place of Justice: A Story of Punishment and Deliverance (New York: Random House, 2010), 97; Woodfox, Solitary, 158.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 158, 159; Rideau, In the Place of Justice, 47.

- Felber, Those Who Know Don’t Say, 72; Bobby Seale, “The Black Panther Party and Community Organizing: An Interview with Bobby Seale,” interview by Audrey Crescenti, Platypus Review, February 2019, https://platypus1917.org/2019/02/03/the-black-panther-party-and-community-organizing-an-interview-with-bobby-seale%EF%BB%BF/.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 158; Ed Pilkington, “The Scars of Solitary: Albert Woodfox on Freedom after 44 Years in a Concrete Cell,” Guardian, February 19, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/19/albert-woodfox-interview-solitary-confinement-44-years; Herman’s House, directed by Angad Bhalla (Toronto, Canada: Storyline Entertainment, 2013), DVD.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 179, 180; King, Bottom of the Heap, 141, 223.

- Jeff Forret, “Slaves, Poor Whites, and the Underground Economy of the Rural Carolinas,” Journal of Southern History 70, no. 4 (November 2004): 790; Francis Lam, “How Thomas Downing Became the Black Oyster King of New York,” Splendid Table, March 14, 2018, https://www.splendidtable.org/story/2018/03/14/how-thomas-downing-became-black-oyster-king-new-york; John T. Edge, “The Welcome Table,” NPR, originally published in Oxford American, 2000, https://legacy.npr.org/programs/morning/features/hiddenkitchens/stories/week13/edgearticle.pdf; Nina Hemphill Reeder, “Civil Rights and Bites: These Black-Owned Restaurants Fed and Fostered the Civil Rights Movement,” Essence, February 19, 2019, https://www.essence.com/lifestyle/food-drinks/civil-rights-black-restaurants/; Elexus Jionde, “A Buffet of Black Food History,” Intelexual Media, February 27, 2021, YouTube video, 22:39, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gbdWNXwQGCc; Ian McNulty, “The Extraordinary Life of Leah Chase,” Gambit, May 21, 2012, https://www.nola.com/gambit/news/article_feef923d-06a4-5955-81ad-dabe6eab3498.html.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 111.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 112.

- Felber, Those Who Know Don’t Say, 55.

- “For the Price of Blood,” Angolite, September/October 1979, Amistad Research Center; Woodfox, Solitary, 195, 198.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 34; Henry Cage, Angola Prison Questionnaire, n.d., box 72, collection 117, Thomas C. Dent Papers, Amistad Research Center; Anne Butler and C. Murray Henderson, Angola: Louisiana State Penitentiary; A Half-Century of Rage and Reform (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 1990), 161; “History of Angola,” Angola Museum at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, accessed November 1, 2020, https://www.angolamuseum.org/history-of-angola.

- Butler and Henderson, Angola, 53, 54; Woodfox, Solitary, 34–35. For information about sugarcane harvest work, anti-Blackness, and prisoner mortality in Texas, see Ashanté M. Reese, “Tarry with Me: Reclaiming Sweetness in an Anti-Black World,” Oxford American, March 23, 2021, https://www.oxfordamerican.org/magazine/issue-112-spring-2021/tarry-with-me.

- Butler and Henderson, Angola, 18; Woodfox, Solitary, 34.

- Rachel Aviv, “How Albert Woodfox Survived Solitary,” New Yorker, January 8, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/01/16/how-albert-woodfox-survived-solitary; Rideau, In the Place of Justice, 147; Grace Toohey, “Angola Closes Its Notorious Camp J, ‘a Microcosm of a Lot of Things That Are Wrong,’” Advocate, May 13, 2018, https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/crime_police/article_b39f1e82-4d84-11e8-bbc2-1ff70a3227e7.html.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 96; Woodfox v. Cain, 609 F.3d 774 (5th Cir. 2010).

- Wilbert Rideau and Billy Sinclair, “Prisoner Litigation: How It Began in Louisiana,” Louisiana Law Review 45, no. 5 (May 1985): 1061–1076; Woodfox v. Cain, No. CIVA 06-789-JJB, 2008 WL 5095995 (MD. La. Nov. 25, 2008).

- Alexander and Woodfox, “Opening Keynote.”

- Woodfox, Solitary, 163.

- Woodfox, Solitary, 183–184, 200, 405; Safiya Bukhari, The War Before: The True Life Story of Becoming a Black Panther, Keeping the Faith in Prison, and Fighting for Those Left Behind, ed. Laura Whitehorn (New York: Feminist Press, 2010). Revolutions in Cuba and China left significant impressions on leaders in the BPP such as Huey Newton. At the Manhattan House of Detention, known as “The Tombs,” Woodfox was given a copy of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book. Woodfox, Solitary, 64; Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 69.

- “All of the Angola 3 are Now Free,” Angola 3, accessed July 12, 2021, https://angola3.org; Helen Vera, “After 42 Years in Solitary, Herman Wallace Dies a Free Man,” October 4, 2013, https://www.aclu.org/blog/smart-justice/mass-incarceration/after-42-years-solitary-herman-wallacedies-free-man; Holly Genovese, “‘The Only Panthers Left’: An Intellectual History of the Angola 3” (working paper, Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice working paper series, University of Texas at Austin School of Law, July 2019), https://law.utexas.edu/humanrights/projects/the-only-panthers-left-an-intellectual-history-of-the-angola-3/.

- Holly Genovese, “The Power of Candy: Celebrating Robert Hillary King’s Freeline,” June 29, 2017, Hampton Institute, https://www.hamptonthink.org/read/the-power-of-candy-celebrating-robert-hillary-kings-freeline; “Closing Statement,” Making and Unmaking Mass Incarceration: The History of Mass Incarceration and the Future of Prison Abolition, accessed July 12, 2021, https://mumiconference.com; Mariame Kaba, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice, ed. Tamara K. Nopper (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021).