“It is the sense of place going with us still that is the ball of golden thread to carry us there and back and, in every sense of the word, to bring us home.” —Eudora Welty, “Place in Fiction,” 1957

Food is the sensory landscape of Laos. In the city streets of Vientiane, smoke rises from grilling fish, chicken, and pork. Lower to the ground, vendors turn soft and short bananas evenly over charcoal. A fruit vendor rings his bell as he bicycles down the street. There is no explanatory sign or text; the gleaming fruits declare themselves on their own terms. Red and spiny rambutan, green raw mango (paired with spiced salt), and pale, chewy yellow corn gleam from behind the glass. Mopeds dart in and out of traffic, which slows as drivers judge the pineapples for sale on the back of a parked truck. The talats (markets) overwhelm you with a kaleidoscope of produce. Maneuvering through the heavily laden tarps, tables, and bargaining shoppers is a feat. Herbs and bitter greens lie beside parts of plants you never thought to eat: the leaves of squash and galangal flowers. Vientiane embraces a bend in the Mekong River, and even here, in the country’s largest city, men and women fish in its waters. You see them heading home at dusk with shining silver fish in plastic crates. Venture just beyond the urban center and the landscape opens into lush rice paddies. Green papayas hang on drooping branches just steps from the kitchen and the mortar and pestle that will pound flavor into their flesh.

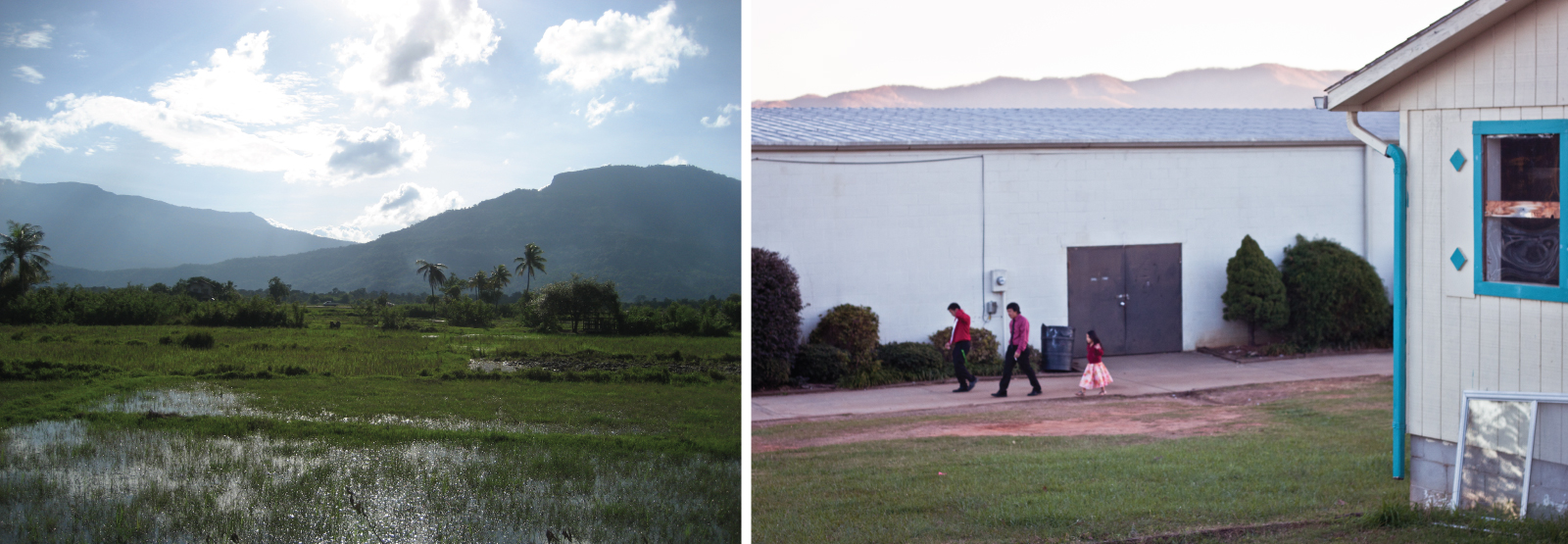

This is the world the Phapphayboun family left behind upon moving to the United States. Toon Phapphayboun, one of three daughters and a son, was the first to leave Vientiane. She did so by canoeing and swimming across the Mekong, fleeing a repressive regime heralded by the rise of the communist Pathet Lao party. She arrived in Los Angeles in 1981. Eleven years later, she successfully helped the rest of her family leave Laos for the United States. After living in California and Connecticut, the Phapphaybouns almost entirely reunited in Morganton, North Carolina, in 2003.

It was in Morganton, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, that I first met Toon and her family. At the time, I was seeking connections to the Hmong community in western North Carolina to investigate current textile traditions. Instead, the Phapphaybouns’ enthusiastic welcome and love of their country pulled my work in an entirely different direction. Between November 2013 and May 2015, I visited Morganton ten times and I overlapped with some of the family in Vientiane for six weeks during July and August 2014. I completed over nineteen interviews, many with Toon acting as translator. I continue to be great friends with the Phapphaybouns, who are generous in both their stories and their hospitality. As so often happens during fieldwork, my initial questions were answered patiently, but it took months of spending time with the family before I began to understand the heart of their way of being in this world.

By seeking to understand such everyday arts—through the generosity of those we interview—we seek to understand life itself.

Looking for textiles, I met the Phapphaybouns. Throughout the course of my fieldwork, I have found more similarities than differences between textiles and foodways. Each art form is an indelible part of our everyday lives. We wake in the morning, dress, eat, and our day begins. By examining a weaving we can learn about a culture’s taste preferences, technological developments, the influence of trade, and social norms—and the same can be said of the foods on the dinner table. Both humble and sublime, each art speaks of histories complex and intertwined. By seeking to understand such everyday arts—through the generosity of those we interview—we seek to understand life itself. What follows is an adaptation of my larger research project, with particular attention to the most sacred space for the Lao community in Morganton: Wat Lao Sayaphoum.

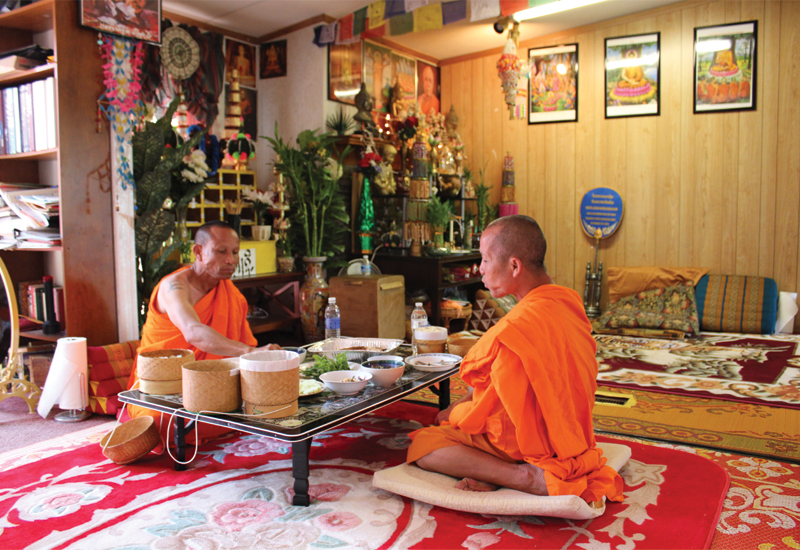

The Phapphaybouns’ togetherness is a triumph over history and circumstance, and the family asserts their Lao heritage daily. Upon moving to Morganton, the Phapphaybouns embarked on remaking Laos in the mountain South. Their world is split across three primary realms: their family homes; Asian Fusion Kitchen restaurant and its adjacent grocery; and Wat Lao Sayaphoum, the Buddhist temple the family helped found, now situated in a double-wide trailer and carport in the surrounding hills. There, amidst the intricate altar display and golden Buddhas, the connection between cooking and sharing traditional foods and the Lao worldview grows evident.

Across each of these worlds, and in their intersections, traditional foodways knit together the different threads of Lao identity while granting the Phapphayboun family a foundational strength. It is the taste of Laos, played out in papaya salad and chilies, that enables the Phapphaybouns to express their heritage among one another, the local Lao community, and other Morgantonians. Through my time in Morganton and in Laos, I also began to see how food is integral to the Lao Buddhist faith. For the Lao, offering a meal to a guest at the kitchen table is the same spiritual gesture as making an offering to Buddha. For Lao displaced from their home, these acts nurture a feeling of being at home in the world.

Across each of these worlds, and in their intersections, traditional foodways knit together the different threads of Lao identity while granting the Phapphayboun family a foundational strength.

From Vientiane to Morganton

When I ask the Phapphaybouns and their relatives why they chose to settle in Morganton, a small city surrounded by hilly countryside, they always provide the same answer: It is a little bit like Laos. The two distant places—one in Asia, one in North Carolina—share a similar mountain foothills landscape, a tie viscerally felt by the Lao families. When Toon’s brother-in-law Daniel Phrakousonh visited Morganton before moving there, he thought, “It looks like Laos! A lot of trees, a lot of mountains. Plus, at that time, I was considering the cost of living . . .When I came down here it was quiet [and] there was a lot of time for family and outdoor activities.” Families like the Phapphaybouns are helping transform the South, and Asian Americans are one of the fastest-growing populations in North Carolina. In 2000, the census recorded that North Carolina’s Asian population was 1.4 percent of the entire state. By 2010, the figure had nearly doubled to 2.6 percent. However, the history of why Southeast Asian groups began to settle in the region is missing from popular understanding—despite America’s role in this migration.1

Laos is the only landlocked nation in Southeast Asia, and its top-heavy shape is defined by the course of the Mekong River, which winds its way from remote highlands to the South China Sea. Positioned between China and Burma to the north and northwest, Thailand and Cambodia to the south, and Vietnam to the east and southeast, Laos is a relatively small country (roughly the size of Great Britain). Its population today is under 7 million—tiny in comparison with the 68 million people living in neighboring Thailand. Laos is a nation defined in the nineteenth century at the hands of external powers. As the French mapped boundaries for their new colony in 1893, they encircled nearly fifty different ethnic groups, who spoke variations of five different linguistic families. As Bernard Fall, one of the earliest historians to write on the Vietnam War, observed, Laos was “neither a geographical nor an ethnic or social entity, but merely a political convenience.”2

In the simplest of terms, Laos defines itself by three ethnic and geographic divisions: the highlands or mountains, which are largely Hmong (an ethnic minority with roots in ancient China); the foothills, which are home to a more diverse set of peoples, many of them also animist; and the lowlands, where the Lao Loum live. This is the majority ethnic group of Laos, and the practitioners of its national religion, Theravada Buddhism. Following the French departure in 1953, the old royal family in Luang Prabang and new statesmen in Vientiane formed the Royal Lao Government (RLG). While the Lao Loum were optimistic about the notion of independence under the RLG, Laos was soon engulfed by the turmoil in Southeast Asia.

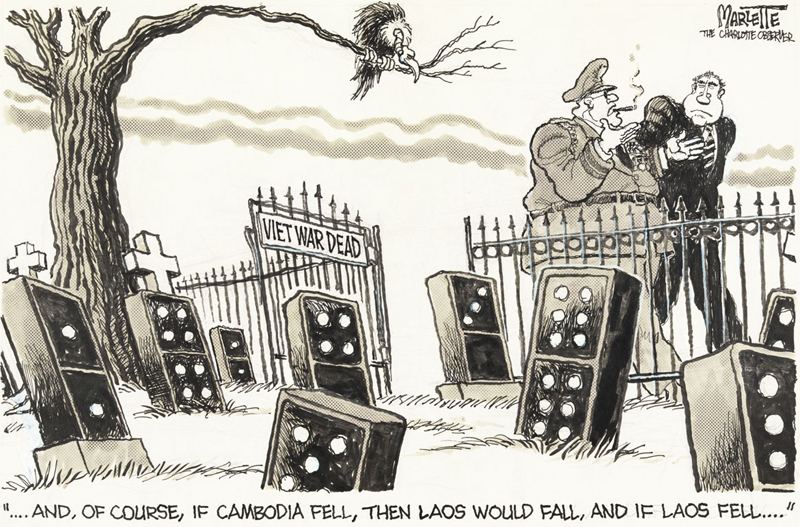

As the conflict in Vietnam worsened, President Eisenhower began covert interventions in Laos that would last into the Johnson Administration. In support of the RLG, and against the threat posed by the rising communist party Pathet Lao (or Lao State), the CIA enlisted willing locals in what became known as America’s “Secret War.” Fighters were largely Hmong, who sought independence from any government—including the Pathet Lao. At its peak, this army numbered 30,000. By paying the Hmong to fight an American war, the United States technically adhered to the 1962 amendments to the Geneva Accords. Meanwhile, they dropped more than two million tons of bombs on Laos—when averaged, a bomber left base every eight minutes for nine years. Much of this artillery targeted the Ho Chi Minh trail, which ran through southeastern Laos. Despite American attempts, in May 1975, the Pathet Lao took over Vientiane. Seven months later, the nation was renamed the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (LPDR). American intervention failed, and today national and international teams continue to remove tons of unexploded ordnance from the Lao countryside.3 Following the Pathet Lao takeover, the LPDR embraced restrictive policies that isolated the country from the rest of the world. Between 1975 and 1985, 10 percent of Laos’s citizens left the country as refugees. The intellectual and middle to upper classes of lowland Laos joined tens of thousands of Hmong (who now faced retaliation) in making dangerous journeys across mountains and rivers in search of a new home. With the war in Laos unreported in the United States, the nation’s newest citizens slowly rebuilt their lives and families while bearing the burden and memory of their country’s untold history.4

The Phapphaybouns, like so many other families in Laos, were intimately affected by this turmoil. Toon’s birth father, La Phapphayboun, was a mayor and faithful to the RLG party. In 1974, La was assassinated while campaigning for a local gubernatorial seat. Toon’s mother, Noubath, was left to raise her four children—Khattana, Toon, Daraphone (Dara), and Noh—alone for seven years. In 1981, she married Khamsi Bounkhong Siluangkhot. When they met, Khamsi was newly freed from a Pathet Lao–run “re-education camp.” When a close friend with political connections offered to take Noubath’s children to Thailand by posing as their mother, Toon jumped at the opportunity: “I left Laos with no idea of where I wanted to be . . . But I said, ‘You got to send me . . .’ I told my Mom, ‘Just send me. I’ll just deal with whatever.’”5

Fourteen-year-old Toon left Vientiane on May 30, 1980. Her friend’s connections spared her years in limbo between refugee camps, and she arrived in Los Angeles on January 13, 1981. In the following years, she helped the rest of her family immigrate to the United States, and they initially settled in California and Connecticut. In 1994, her newlywed sister Dara moved to Morganton, North Carolina, in search of work, a low cost of living, and a sense of familiarity to Laos. By 2003, the Phapphaybouns were nearly entirely reunited in North Carolina—at last, Noubath, who “came to America to create her Laos,” as Toon says, could enjoy having three of her four children and their families together.6

Many of the Southeast Asians who moved to North Carolina after the 1980s came from elsewhere in the United States, making a “second migration.” Before the 1980s, the South was not a destination for immigrants, as industry in the region was small enough at the time to draw its workforce from local white and black populations. However, Morganton, the oldest settlement in western North Carolina, is an anomaly. Commissioned as the seat of Burke County in 1784, Morganton first prospered as a railroad stop before the establishment of lumber operations, furniture factories, and textile mills. The success of these industries required immigrant labor earlier than other parts of the South. French-speaking Waldensians from Italy settled in and around Morganton at the turn of the twentieth century, and the region’s most recent wave of immigrants—indigenous Maya from Guatemala—began arriving in the mid to late 1980s. Between these two movements, Hmong refugees from Laos came to the region in increasing numbers, aided by churches and charities. In the following decades, Lao and other Southeast Asian groups began to arrive in western North Carolina, where the construction of Interstate 40 in 1960–6 sustained local industry.7

Toon shook her head in amazement, saying, “If you didn’t know me, it’s a fiction, isn’t it?”

Today, there are roughly forty Lao families living in Morganton and the surrounding areas. Many Southeast Asians continue to work in manufacturing jobs, while the Hmong community is earning a reputation for their farming. Toon received her BA from University of California Santa Cruz, an MA in English from Cal State, and today she is an English and Spanish instructor at Western Piedmont Community College. Reflecting on her and her family’s journey during one of our interviews, Toon shook her head in amazement, saying, “If you didn’t know me, it’s a fiction, isn’t it?”8

Making Home in North Carolina

In this corner of the South, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Phapphaybouns have successfully created a highly personal version of Laos. Reunited and living across two homes, the family has adapted these spaces to reflect their identity and support cultural traditions from everyday cooking to sacred gatherings. Dara, the youngest daughter, has extended her family’s values and love of cooking into Asian Fusion Kitchen and Lao Lanxang Grocery, adjacent businesses in an unassuming strip mall roughly two miles from downtown. Through her restaurant’s menu and its Lao decorations, Dara proudly initiates locals into Lao cuisine, perpetuating a legacy of family cooking rooted in the soil and waters of Laos and reinterpreted in the mountains of North Carolina.

The Phapphaybouns live in two households that are tucked into the suburbs of Morganton four miles apart. Both houses are one-story ranch homes, typical of their neighborhoods, but the family has adapted them to suit their needs and tastes in a powerful articulation of culture and heritage. With nine family members sharing two modestly sized homes, the atmosphere is lively and convivial. Food brings the family together, and the kitchen is the center of both houses. In Laos the kitchen (heuan khua), cooking, and eating define family (kawp khua) life: the terms for each even share a word. Following the model of kitchens in Laos, which are nearly always outdoors, Noubath transformed the porch of Dara’s house into a semi-outdoor kitchen. In winter, the screen windows are covered with plastic to keep the heat in, but in summer, warm breezes flow freely through the space. With two stoves, a sink, a refrigerator, two work tables, improvised counters, and two shelving units, there is still barely enough room to contain her cooking. “This is my house,” explained Noubath proudly, as she peeled a fragrant lime on a May morning. While Noubath’s daughter-in-law Meemee’s kitchen is not quite as elaborate, it is also the center of her home and extends outside. Noh installed a grill, stove, and a small roof with a light on the back deck. Here, Meemee uses stock pots to cook curries and broths for large gatherings and Noh grills, rain or shine.9

A strong foundation at home enables the Phapphaybouns to share this world beyond their friends and relatives.

In customizing their Morganton homes in this manner, the Phapphaybouns purposefully integrate the home life and social connection they experienced in Laos. In Laos, it is common to sit, visit, and linger for so long after a meal that, as Toon says, “lunch turns into dinner and we eat again.” When I visited Toon and her family in their Vientiane neighborhood Ban Sikai, we did just that. Without our leaving the table, small personal plates were swapped out for clean ones, more entrees came from the kitchen, less full serving dishes were combined, and beer glasses filled for another round of socializing. Long, convivial meals like this were the center of the day, often combined with a walk around the neighborhood and visits to family and friends. In Morganton, and across western North Carolina, families are divided by larger distances, and the impromptu visiting they knew in Laos is not possible. Drawing together the community becomes more difficult, yet more meaningful. To make up for the distance between families in North Carolina, the Phapphaybouns make their homes the sites of annual celebrations, supported by their customized kitchens.10

A strong foundation at home enables the Phapphaybouns to share this world beyond their friends and relatives. Dara and her husband moved to Morganton to begin work at Valdese Weavers, a textile manufacturer, but Dara soon began to dream of the freedom of running her own business. She explained, “I said, ‘One of these days I am going to [start] a business and try to bring [the family] together.’” In 2010, she opened the Lao Lanxang grocery store, named for Laos’s ancient monarchy. The prepared foods she sold with Noubath on Thursday nights grew so popular that she could imagine a successful restaurant. In 2013, Dara rented two adjacent storefronts on West Fleming Drive and opened the second iteration of Lao Lanxang next to her new restaurant, Asian Fusion Kitchen. Dara is the only chef, by her choice. She works twelve-hour days six days a week, but in her words: “To cook, for me, is not work. It’s something I enjoy.” The restaurant is a success and during a recent phone interview, Dara told me that on a scale of one to ten, her restaurant is at a seven—this after opening just two and a half years ago.11

Asian Fusion Kitchen is a direct connection to the culinary and cultural worlds of Laos. However, Dara also has designed the space and her menu to gently invite others to learn about her homeland. This is a powerful introduction in a place where the Lao community is small and Laos is largely unknown by locals. Dara explains, her restaurant “bring[s] something out to show everybody where I come from, who I am, and why I do what I do, because I wanted to introduce everyone to Laos. Because everybody says, ‘Hey, you Chinese.’ Laos never exists! That’s why I said I’m going to open a restaurant or grocery store one day, and I’m going to tell them, ‘I’m not Chinese, I am Lao.’”12

Even as Dara seeks to assert her Lao heritage, she chose the name Asian Fusion Kitchen to quell customers’ anxiety about the unknown or possible trepidation about spicy food. For her, the concept of “fusion”—blending new with old, Lao with Thai or Chinese—is also key. She acknowledges that her menu combines aspects from these regions, but asserts her food is special because of its impeccable freshness—central to the spirit of cooking in Laos. While they were operating out of the Lao Lanxang grocery, her mother Noubath prepared traditional Lao dishes for her daughter to sell. These included pho, kao poon (a coconut noodle soup made with beef, chicken, or fish), Lao-style papaya salad made with padaek, sticky rice with sausages, sesame rice balls, fried dough, and fried rice crackers. Now that she is in charge of the cooking, Dara’s sixteen-item menu at Asian Fusion includes only two distinctly Lao dishes: papaya salad and naem khao (a crispy rice salad made with fermented pork). She explains, “My mom cooks in the real old ways, so I take her as a guideline. Nowadays, people like more and different things, so I add new things to my Mom’s [cooking]. It is still authentic, but I can add something commercial . . . throw America and Asia together a little bit.” Lao and Hmong know to order off-menu, but Dara also serves American favorites such as chicken wings, pad thai (the bestseller), and spring rolls. Chuckling with a sparkle in her eyes, she reminded me that customers can always order any dish mild, hot, or “Lao”—if they dare.

Despite the distance between the South and Laos, the native cuisines of the regions share characteristics that bring the two traditions into conversation. Both are historically agrarian societies that value thriftiness in food preparation. Just as transforming every part of a hog into food was (and is) a necessity for poor families in the South, clever Lao cooks turned cuts of meat that were discarded by people with greater means into delicious dishes. Because most of the country was historically poor, and few had regular access to meat, Lao cooking has always utilized as much of the animal—whether fish, duck, or pork—as possible. In response to today’s trendy whole-hog eating, food writer and chef Nancie McDermott asserts, “Nose-to-tail eating, Asia never stopped!” Known in the South as curing, culturing, or souring, fermentation is also fundamental to Lao cuisine. The sour pork and pickled fish Noubath is known for are fermented, as is padaek, the key marker of Lao flavor. In Lao, there is a special term for foods that require much preparation before they can be edible: ahan vieg (work food). This term also works nicely for shelling field peas or fermenting watermelon rinds, examples of the ingenious labor undertaken by southern cooks. Underneath contrasting flavors, similarities between southern and Lao cooking are easily found, and may contribute to Morgantonians’ enjoyment at Asian Fusion Kitchen.13

To eat a dish at Asian Fusion Kitchen is to connect to the Phapphayboun family’s rich food heritage in forms adapted for Morgantonians. As food reinforces family bonds in Laos and at their two Morganton homes, eating and sharing foods at Asian Fusion Kitchen allows the Phapphaybouns to share the essence of their home(land) with others. In this way, the restaurant becomes a public foundation for their interactions with others. As a result, not only does the local Lao community have a gathering place and a convenient source for specialty ingredients, but Morgantonians also are presented with an opportunity to experience Laos. The Phapphayboun family is extraordinarily welcoming, so much so that regulars are often invited to sit at the family (or “VIP“) table near the kitchen. “We’ve adopted people,” says Toon, “we have a VIP table with eight chairs and sometimes you have to pull more chairs because there are more people. It’s a gathering place for food and conversation.” Pam Roths, who first visited Asian Fusion Kitchen a year ago, jokes, “I went looking for pho and I found family.” She is proud to see how Morgantonians come in to support Asian Fusion Kitchen. She attributes this willingness to the changing spirit of the town as people have left—either for education or in pursuit of work—and returned, to the welcoming Phapphayboun family, and Dara’s irresistible cooking. In Morganton, news still spreads primarily by word-of-mouth and Asian Fusion Kitchen is part of the conversation. Pam is starting to hear others use the family’s nickname for the restaurant, “AFK”—a play on KFC.14

Food and Faith Carry a World

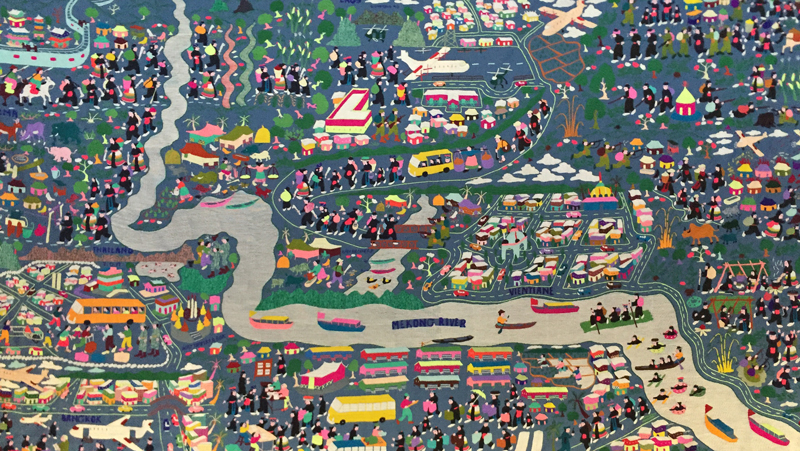

Noubath hands me a silver offering bowl and fills it with three small bananas, two sesame-covered fried desserts, a lunch-box sized orange juice, and a Kellogg’s Rice Krispy Treat in crinkly blue packaging. Folding a piece of notepaper with quick movements, she transforms it into a neat cone and tucks my bills and two yellow flowers inside. In a few moments, I am ready with offerings for Pii Mai, the Lao New Year. Sitting with Noubath, Meemee, and her sister Airsikhay Ammalathithada (Air) on the soft, carpeted floor toward the front of Wat Lao Sayaphoum’s worship room (sim), we watch Khamsi excitedly help the two monks bring more flowers from the kitchen to the altar. With so many candles lit, the altar shines in a richly ornamented collage. At its base, small bowls of food, candles, and white blossoms are arranged on trays. Toon is sitting in a chair near the back of the room, which is now full of families filling offering bowls or paper-clipping bills to one of the three money trees. Air hands me a long, thin yellow beeswax candle and shows me how to hold it against my body and kink it in lengths corresponding to my torso, forearm, and head. We bend our candles in three and pass them to the front, where a monk now sits at his station below the large gold Buddha at the altar’s center. Taking just a handful of our candles—there are so many on this special day—he twists them into a single mass. “It symbolizes the community of souls coming together,” Toon later explains. The room grows quiet, and Khamsi and a few other men near the altar begin the ceremony with words of welcome in Lao. The monk lights the mass of candles, and as the call-and-response chanting in the ancient Buddhist Pali language begins, he slowly turns the ever-bigger flame over a bowl of water.15

Wat Lao Sayaphoum, a Lao Buddhist temple tucked into the hills roughly thirteen miles outside of Morganton, was the busiest I had ever seen it. On this Saturday in April, one of the year’s first warm days, the community came together in celebration and the temple was dressed to the nines. At this temple, through the course of the Pii Mai New Year celebration, smaller ceremonies, and mid-week visits, I began to understand how cooking and sharing traditional foods is an essential medium of Lao devotion. The rituals and aesthetics of Wat Lao Sayaphoum make visible otherwise unarticulated values that define the Lao worldview. Ceremonies at the temple bring the formalities of Theravada Buddhism to Morganton and reveal the deep ties between food and faith and how both contribute to feeling at home in the world. The offering of food is a central activity at the temple, and for the Phapphaybouns and other Lao Buddhists in Morganton, the transition from offering a dish to the altar and offering to the family table is seamless.

Feeding the Spirit: Food and Religion in Laos

The majority of Lao practice the national religion Theravada Buddhism, which has been called “a richly nuanced epic tale with many subplots.” In Laos, belief in Buddhism is woven together with an older, vernacular belief in spirits both benevolent and malicious. The act of offering food and money to both are important daily rituals. The spirits, or pii, are revered alongside Buddha and are placated with “spirit houses” and daily offerings of sticky rice, water, and other foods. Similarly, donating to the temple or offering food to the monks is the primary way a Buddhist can “make merit,” or ensure good fortune in this life and the next. The spiritual life of the Lao is both intensely mystical (if you trip, blame a pii) and practical: gifts of food and money are foolproof ways to please your ancestors, honor Buddha’s teachings, and placate naughty pii. Through these daily offerings, the Lao ensure good fortune and place giving and hospitality at the very center of their worldview.16

Monks at the neighborhood temple survive on food offered by the laity, and walk morning streets to receive meals during the tak baht ritual. Sticky rice, pinched into neat balls, is tucked into spirit houses and pushed in the mouths of temple guardian figures for good fortune. It is even fortuitous if you offer up foods you know the spirits, or your ancestors, will enjoy. As Toon explains, special dishes are made for temple visits. “Each person will call on whoever passed away in their lives to come and get their offerings . . . That’s why many people, especially my mom, will say, ‘Oh, my mother really likes fish cakes!’ So you would make that and take it to the temple [and] you say, ‘Come and get your fish cakes!’” Temple ceremonies end with a community buffet. After foods brought for the monks are offered in reverence, all are welcome to fill their plates. While giving is central to Buddhism, food is central to giving—and by cooking, sharing, and eating, Lao fulfill their spiritual needs at home and abroad.17

Belief Made Visible at Wat Lao Sayaphoum

Led by Toon’s father Khamsi, the Phapphayboun family helped establish Wat Lao Sayaphoum in 2003. Khamsi is regarded as a wise and experienced leader among the local Lao community. While in Bridgeport, Connecticut, he served on the management teams for both the local temple and family association. Not long after moving to North Carolina, Khamsi drew together other community leaders in the living room of Dara’s home and decided to establish a temple in Morganton. Only about thirteen Lao families lived in the area then, but with their support, Khamsi and the management team transformed a rental house into a temporary temple. In 2005, with community donations, temple leadership bought the trailer and plot of land where Wat Lao Sayaphoum now stands.18

The trailer includes a semi-public kitchen, a secondary altar, and private bedrooms for the temple’s two monks. One monk, Somchit Sengdavone, has lived at the temple since I began visiting in 2014. Visiting monks, drawn from other temples in the United States, periodically join Somchit and contribute to his spiritual development. The community cleared the plot of land of its trees and erected a carport for the temple’s main worship space and altar. The building was erected quickly; as Toon noted, the community “did the Lao thing with construction—they just built it.” The volunteers customized the red-metal-siding carport by designing a front porch in wood and cement. Indoors, the structure’s simplicity is masked by the oranges, golds, and reds of the many Buddhist objects displayed here—including the six-foot-tall golden Buddha donated by Khamsi seated at the center. Wat Lao Sayaphoum, like the Buddhist temples of Laos, is in a constant state of improvement. Humble in size, but with essential elements in place, the temple receives the local Lao community from Morganton and its surrounds, with special ceremonies drawing Lao visitors from as far as Charlotte.19

In order to practice Therevada Buddhism in Morganton, the temple management and its community must reinterpret historical Lao traditions for their utility in the North Carolina foothills: Ceremonies are held on Sundays in deference to the workweek; secular elements, such as alcohol sales and dancing, are added to large festivals to draw crowds; and the tak baht is reinvented. Rather than walking the surrounding streets to receive daily offerings, the monks of Morganton rely on a synchronized delivery of meals by the laity. Three families bring them their early lunch Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and the larger community ensures, through donations, that there are plenty of supplies for them to cook simple meals for themselves Tuesday and Thursday. Khamsi and Noubath deliver the Friday meal. When I joined Khamsi on one of these trips, Noubath sent us with an elaborate, and very traditional, meal: fried fish, sticky rice, a stew which included chicken feet and Lao mushrooms, pickled fish stir fry, and a plate of raw greens. While Noubath cooks regularly for the temple, Air and Dara enjoy doing so for special occasions. On behalf of Asian Fusion Kitchen, Dara will typically donate pho for the Pii Mai celebration, and proceeds from its sale support the temple. Flexibility ensures the survival of these cultural practices and makes the temple a vital community gathering place.

As more people come to the temple, its meaning and significance increases. The larger the community, the closer this space resembles the temples of Laos. As Air explains, the temple “is part of a family, like in Laos. When we have our traditions, we go to the temple, and I feel like I’m in Laos.” One measure of this is the altar itself. The altar, a five-foot-wide platform rising in three steps covered in burgundy carpet, was sparsely decorated in the early days. “Now you can’t see the carpets,” says Toon, “Only statues.” Surrounding the large central Buddha are many smaller statues, shown meditating in different positions. Along the back wall are miniature versions of the tiered umbrellas carried in Lao festival processions. Green, shiny, heart-shaped leaves make up an imitation Bodhi tree to the left of the altar’s center, and flanking each side are pink plastic lotuses in ceramic vases. At Buddha’s feet, above where the monks sit on woven pillows, is an electric candle of the sort Americans put on their windowsills at Christmastime. Various gleaming imitation banana leaf cones and plastic flowers are dispersed across its surface, and a white thread is bound around the largest Buddha and draped from left to right, figuratively tying these sacred elements together.20

At the temple, it is the sense of possibility and hope that is nurtured most deeply.

For the Lao who visit Wat Lao Sayaphoum, the temple and its altar are a North Carolina representation of their neighborhood temple in Laos. The plastic cones and petals on its altar reference freshly made banana leaf and flower originals used at home. Memories fill in the spaces between decorations and help to gloss over the readymade roughness of the worship space. This intimate connection to Laos honors both group and individual beliefs and proclaims: You belong here. Wat Lao Sayaphoum is housed in Morganton but grounded in Laos. Anthropologist Ghassan Hage argues that being at home in the world is “dependent on four feelings: security, familiarity, community, and a sense of possibility or hope.” At the temple, all these feelings come together, but it is the sense of possibility and hope that is nurtured most deeply. As familiar rituals such as the tak baht and community meals are repeated on the sacred grounds of Wat Lao Sayaphoum, the connection between food and faith is reasserted. Lao reaffirm their feeling of being at home in North Carolina beyond the temple through the everyday acts of cooking and eating, and it is in the sharing of these foods that the Lao are able to articulate the deepest sense of their identity.21

Katy Clune received her BA in art history from UC Berkeley (2008) and her MA in folklore from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (2015). This essay is derived from her eponymous master’s thesis. Clune is engaged in cultural communications—writing, design, and multimedia storytelling—to build bridges between diverse peoples, and institutions and their audiences. You can learn more about this project at makinglaos.com and more about Clune’s work at katyclune.com.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Katy Clune.NOTES

- Danil Phrakousonh, interview by Katy A. Clune, Morganton, NC, September 20, 2014; “Race, North Carolina, 2000,” U.S. Census Bureau, prepared by Social Explorer, http://www.socialexplorer.com/tables/C2000/R10932136?ReportId=R10932136, accessed April 12, 2015; In 2010, there were a recorded 205,335 Asian Americans living in North Carolina. Of this, 10,433 were Hmong, compared with 5,566 Lao. “QuickFacts Beta, North Carolina,” U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/RHI425213/00,37, accessed April 12, 2015; Scholarship on Lao immigrants to the United States is extremely limited. Much of the literature deals with the Hmong, not Buddhist, Lao. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, by Anne Fadiman (New York: The Noonday Press, 1997), is likely the most influential account of one Hmong family’s experience in California. There is essentially no research on Lao in North Carolina. This essay is in conversation with Barbara Lau’s “The Temple Provides the Way: Cambodian Identity and Festival in Greensboro, North Carolina” (Master’s thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2000).

- “East and Southeast Asia: Laos,” Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/la.html, accessed April 12, 2015; Grant Evans, ed., Laos: Culture and Society (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1999), 26; Bernard B. Fall, Anatomy of a Crisis: The Laotian Crisis 1960–1961 (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1969), 24, 23.

- Fadiman, The Spirit Catches You, 130, 131.

- Martin Stuart-Fox, Laos: Politics, Economics, and Society (London: Frances Pinter Publishers, 1986), 53.

- Nearly 20,000 of the country’s best and brightest were sent to these notorious labor camps. Judy Rantala, Laos Caught in the Web: The Vietnam War Years (Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2004), 178; Toon Phapphayboun, interview by Katy A. Clune, Vientiane, Laos, July 28, 2014.

- Noubath Siluangkhot, interview by Katy A. Clune, with translation by Toon Phapphayboun, Morganton, North Carolina, March 10, 2014.

- Tom Hanchett, “A Salad Bowl City: The Food Geography of Charlotte, North Carolina,” in The Larder: Food Studies Methods from the American South, eds. John T. Edge, Elizabeth Engelhardt, and Ted Ownby (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013), 169–170; Labor historian Leon Fink provides an excellent account of the Mayan population in Morganton in The Maya of Morganton: Work and Community in the Nuevo New South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Fink, Maya of Morganton, 8.

- Toon’s parents Khamsi and Noubath help manage the Lao Family Association of Morganton, a social aid group with membership of roughly forty families, or eighty individuals, stretching from Morganton to Hickory to High Point. Khamsi Bounkhong Siluangkhot, interview by Katy A. Clune, Morganton, North Carolina, September 21, 2014.

- Monica Janowski and Fiona Kerlogue, eds., Kinship and Food in Southeast Asia (Copenhagen: Nias Press, 2007), 230; Noubath Siluangkhot, interview by Katy A. Clune, with translation by Toon Phapphayboun, Morganton, North Carolina, May 11, 2014.

- Toon said this during a meal together in Ban Sikai, Vientiane, Laos on July 13, 2014.

- Daraphone Phrakousonh, interview by Katy A. Clune, Morganton, North Carolina, March 10, 2014; Daraphone Phrakousonh, phone interview by Katy A. Clune, May 19, 2015.

- Daraphone Phrakousonh, March 10, 2014.

- Nancie McDermott, interview by Katy A. Clune, Raleigh, North Carolina, April 18, 2014; Chef and owner of Farmer’s Daughter Preserves April McGreger says that fermentation is the foundation of southern food: “It cannot be overstated.” April McGreger, email to author, March 22, 2015.

- Noubath Siluangkhot and Toon Phapphayboun, March 10, 2014.

- Toon Phapphayboun, April 12, 2014; According to Theravada Buddhism, older respected men will assemble near the front altar and assist the monks in coordinating the ceremony, while women, children, and other men gather just behind.

- Donald K. Swearer, The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 61.

- Khamsi Bounkhong Siluangkhot, interview by Katy A. Clune, Morganton, North Carolina, May 11, 2014.

- Ibid.

- According to Lao Buddhism, monks are required to stay at one temple for three months during Buddhist Lent each year. Beyond this, they can travel to other temples. At least three, even better four, monks are needed to best conduct ceremonies and associated chanting rituals. The Morganton temple leadership frequently invites visiting monks to stay for a period. In doing so, the guest monks contribute to the spiritual development of resident monk Somchit Sengdavone and elevate the sacredness of Wat Lao Sayaphoum. Martin Stuart-Fox and Somsanouk Mixay, Festivals of Laos (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2010), 59; Khamsi Bounkhong Siluangkhot, September 21, 2014.

- Airsikhay Ammalathithada, interview by Katy A. Clune, Morganton, North Carolina, September 21, 2014; Khamsi Bounkhong Siluangkhot, May 11, 2014.

- Ghassan Hage, “Migration, Food, Memory, and Home-Building,” in Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates, eds. Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010), 418.