“What does a liberated life mean for queer southerners and for the folks around us? When will home accept us?”

As a child in Birmingham, I saw girls visit my masculine-presenting neighbor at night. They talked through the screen at her bedroom window. I wondered why I’d never see them enter the house, and it wasn’t until I was older that I realized that my neighbor was queer. She unfortunately passed away at a young age. But I never forgot her because I often saw myself in her. The ways she walked boldly wearing long tees, baseball caps, and Jordans. I knew I’d grow up to be like her in so many ways. I’ve always known that I was queer. Maybe not the exact term, but I knew I was different by my looks, likes, and attractions.

Within my home, I experienced a love from my late mother that was deeply connecting, pure, and present. And as an only child, my heart leaned soft toward many of the emotions on the feelings wheel. When I left home for college, I knew that it was time to explore what those feelings meant for a Black teen who was grappling with identity in a new place, no longer under the watchful eye of my mother and close friends. Still, I repressed my deeper, intimate feelings until after college. It was then that I defiantly and confidently began to live beyond the confines of how I was raised. My mother allowed me to come into my identity without judgment, but she feared for my safety. To be out in Birmingham, let alone Alabama as a whole, felt like a betrayal to my family and their religious beliefs. I came to understand how something as simple as who I was attracted to could affect my chances at a beautifully fulfilled life. And I wondered where I could find a community that could offer protection from hate and misunderstandings, and help find an outlet for putting my pain into words.

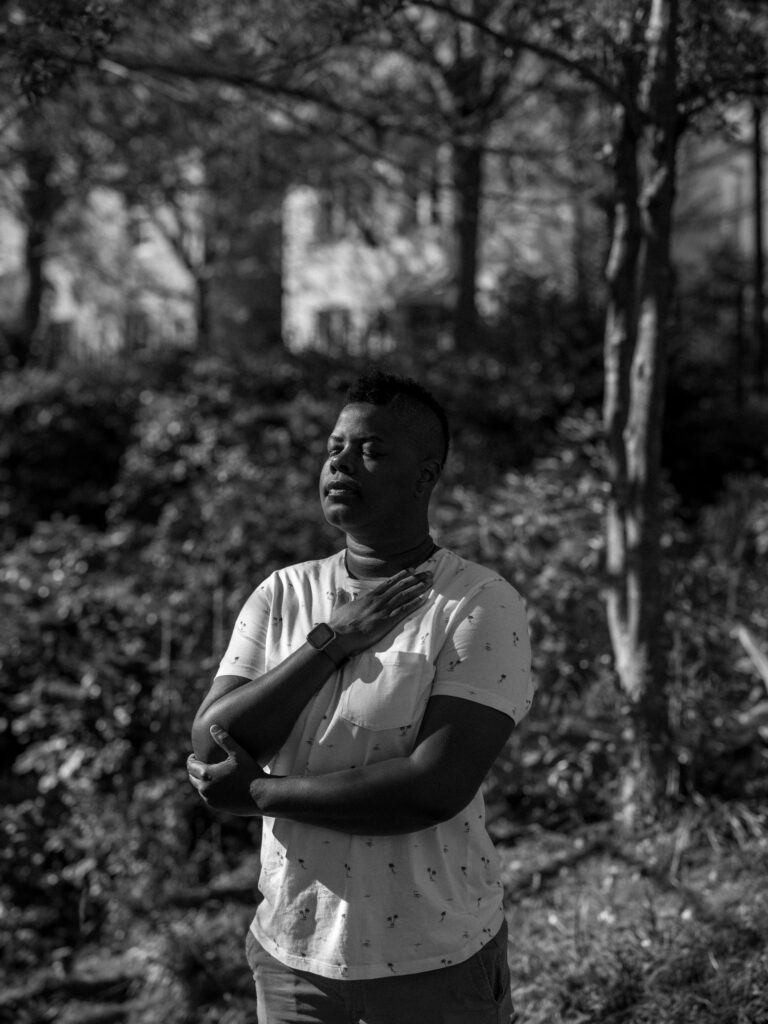

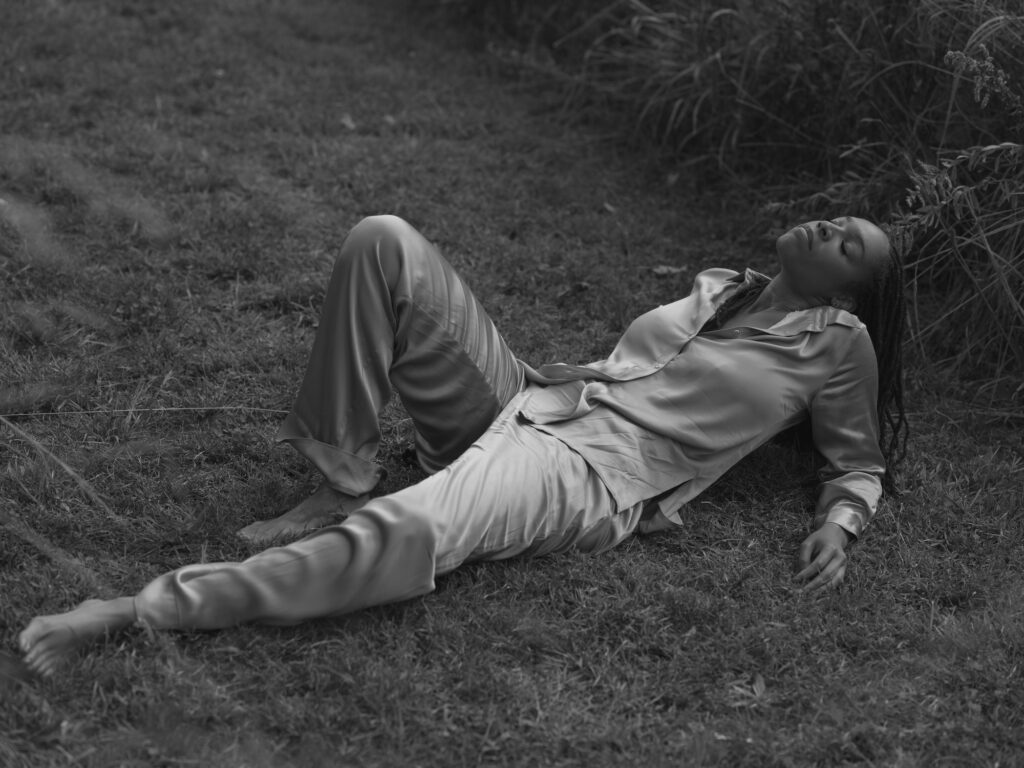

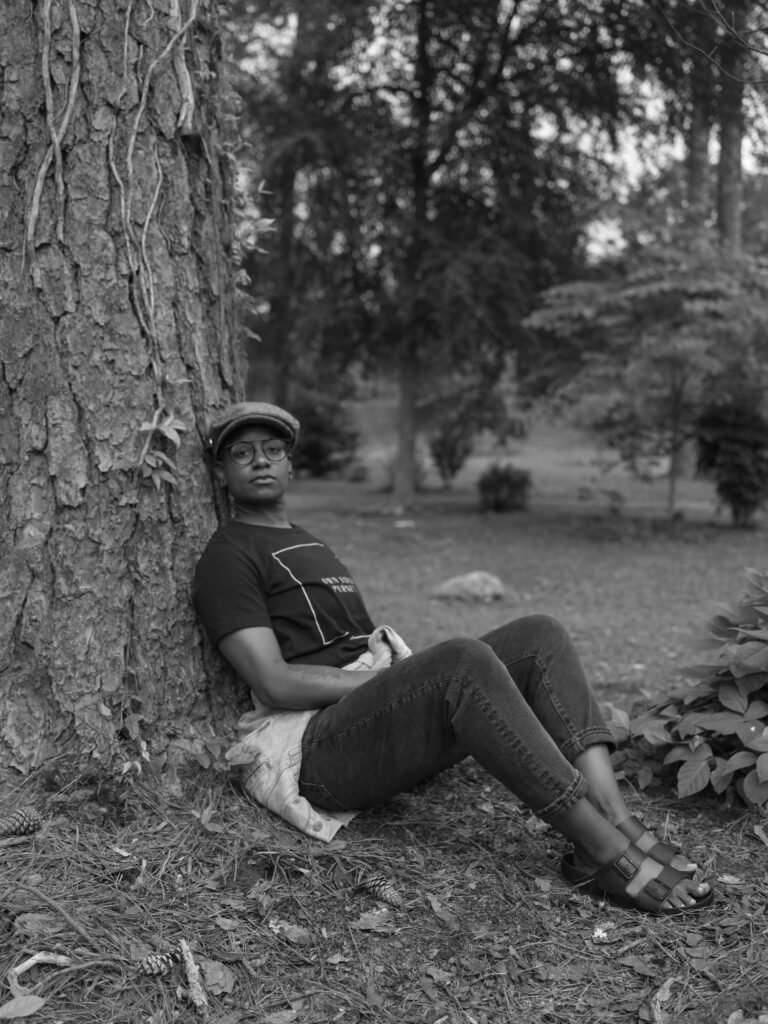

In 2022, I started a body of work, I See Myself in You, centered on Black queerness and questions I’ve long grappled with: How does my southernness interact with or against my queerness? How do I remain hopeful in a climate where my very being is undervalued and unprotected? One thing that sticks out is how abundantly aware we are of our Black bodies, lives, and ourselves when outside of our own constructed communities. We’ve built these internal homes and created chosen families to protect our peace and to navigate the turbulence of grief we sometimes experience living in this region. What does a liberated life mean for queer southerners and for the folks around us? How do we receive joy when our gender expression, reproductive rights, and gender-affirmation care are under constant threat? When will home accept us?

As a child in Alabama, I got to spend time around my great-aunt, who was a foot soldier in the Civil Rights Movement. She modeled for me how to stand up for the rights of all Black folks, including queer folks. If it weren’t for those queer Black folks who were part of the movement, I wouldn’t know that we existed or fought alongside the popular activists we all know. The South showed me that this sacred part of the country gave queer people a place to live, thrive, and conjure liberty and freedom. My great-aunt and our queer predecessors demonstrated how we reconcile being queer and southern and Black. With compassion, visibility, community, and, most importantly, love.

The beauty of the southern experience is in how this place has room for so many people to blossom in their way. Within my own heart, I still feel those huge emotions, but now they’re centered on how to heal from repressing my feelings as a Black teen who felt deeply that my queerness would eventually be my freedom. At the onset of this project, I hope to document others’ freedom, too, and continue to support a beautiful community. And, in doing so, to see myself continually reflected and welcomed home.

Lynsey Weatherspoon’s first photography teacher was her late mother, Rhonda. As a member of a modern vanguard of photographers, Weatherspoon is often called on to capture heritage and history in real time. Her work explores the stories and complexities of her personal identities as a Black and queer woman in the American South.