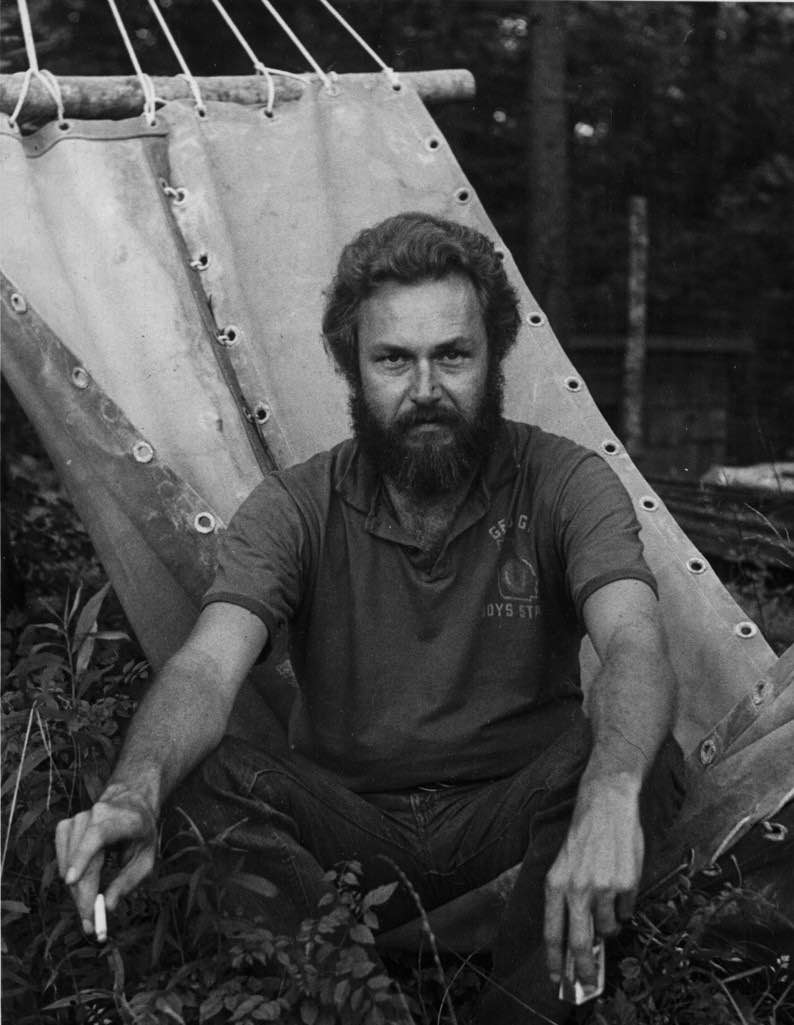

Calvin Yeomans (1938–2001) was in a depressive period in the middle of the 1970s. As he built up what he referred to as his “little island”—Crystal River in central Florida, where he grew up and returned to after a breakdown in 1974—he reflected on his life and artistic output. He was a queer southerner who, like many others, had a complicated relationship with his southern home and sexuality, especially as queer print media increasingly defined queer life as metropolitan. He had lived in New York and Atlanta and had spent a great deal of time in San Francisco. He also had extensive theatre experience. After college, he spent several years traveling and working as a set designer and director in Michigan, North Carolina, and the Catskills. His life in Atlanta included work with the Pocket Theatre and founding the Atlanta School of Acting and Workshop Theatre with Fred Chappell. In 1971, he moved to New York and found work with Ellen Stewart, one of the pioneers of the off-off-Broadway scene, at her Café LaMaMa (later the LaMaMa Experimental Theatre Club). Journal entries from September 1976 to September 1977 reveal Yeomans’s struggle with what to write and how to turn his experiences into something that would resonate with audiences. In September 1976, he wrote, “Why should I, who have had such bizarre and interesting experiences, be devoid of subject matter? What is the little kernel that seems to be missing?” In the Spring of 1977, he again lamented losing the burning zeal for theatre he once had.1

By mid-summer of 1977, he’d returned to writing in the “Southern genre,” though he remained unsure of his message. “Still working on Estelle, but it just seems like a stale, bad, old-fashioned Tennessee Williams play—which I guess is all it is.” He continued, “I write of old women. Are old women all I know of . . . a week from today, I will be in Calif. And wonder if I will find any answers there. Come back with any fresh new perspectives. I certainly am in need of some.” He took two projects with him to San Francisco. The first was the Estelle play and the second was a series of vignettes he called “the despair fragments from NYC.” He claimed they haunted him and would not seem to rest.2

When Yeomans looked to San Francisco, it was one of the most visible and important queer capitals in American queer geography, along with New York. Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, and Miami also boasted recognizable queer communities with a critical mass of queer people congregated around businesses, shops, restaurants, discos, and other gathering places that mostly catered to out queer people, what scholar Jeffrey Escoffier called the “territorial economy.” National publications aimed at queer consumers, like The Advocate for gay men, reinforced this geography and constructed the gay lifestyle as open and metropolitan, peopled by those with access to money who were usually white and conventionally attractive. Rural queers outside of these spaces were directed to leave for one of the cities. Advocate publisher David Goodstein editorialized about queer people leaving rural areas for greater sexual freedom. Edmund White, author of States of Desire, described San Francisco as a refuge “from all those damaging years in Podunk.” Even some scholars of the time echoed metronormative assumptions. In 1984, the activist and scholar Gayle Rubin wrote that “dissident sexuality is rarer and more closely monitored in small towns and rural areas. Consequently, metropolitan life continually beckons to young perverts,” leading to concentrated pools of queer kin. Of course, the lived experience of queer folk, even those in the queer capitals, was often vastly different from the imagined community, as scholar Scott Herring argued in Another Country. Publications like RFD and playwrights like Cal Yeomans challenged the metronormative assumptions and discourses that universalized the experiences of a subset of promiscuous citified gay men.3

Yeomans’s invocation of Tennessee Williams when despairing about his creative output is illustrative. Williams’s work is southern, and profoundly queer, but the magnolia closets that brought him mainstream success were anathema to what many saw as the liberationist project of the burgeoning gay theatre movement. The critical mass of queer people in cities created communities and audiences for queer theatre. After its 1972 debut, Jonathan Ned Katz toured his gay history show, Coming Out!, around the country. Robert Patrick, Robert Chesley, Doric Wilson, George Birimisa, and Lanford Wilson were all writing more openly queer work that celebrated and critiqued modern queer life. In the South, Rebecca Ranson was writing about lesbians in North Carolina, and the Red Dyke Theatre in Atlanta was a key part of the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance. These were works by queer people, for queer audiences.

According to his diary, Yeomans’s trip was sexually eventful, and he spent time with friends at leather bars. He also saw Lanford Wilson’s play The Madness of Lady Bright at the newly opened Theatre Rhinoceros. The show was by an openly gay man and was intended for an openly queer audience in a theatre that was explicitly for queer people. Straight people could enjoy the show, too, but it wasn’t for them. On his flight home, Yeomans wrote in his diary that he “was so struck by this fabulous thing—you could write a play that didn’t make sense for anyone but gay people. It was liberating.” He expressed feeling alive again, as if his life was beginning. “Finally—after a long series of discouraging events and frustrating years—I said ‘Fuck it’ and started writing as honestly as I could—which meant, for me, frequently writing truthfully upfront gay plays.”4

The first show of this period was Richmond Jim, a three-character show about a young man from Richmond, Virginia, who inexplicably finds his way to a leather bar during his first time in New York. He goes home with a man named Mike, who introduces Jim to the pleasures and possibilities of sex beyond homonormative monogamy. “Let all that shit go, man.” Like the ghost of Christmas Future, Mike’s friend Biddy shows him the desolation and futility of finding happiness down the kinky road. Biddy says “One thing leads to another until one day you wake up and discover you are a jaded old thing no longer capable of a simple act of love. It seems the unavoidable way of the homosexual underworld.” The show ends with Jim in full leather regalia and Mike on his knees. Richmond Jim was drawn from Yeomans’s experiences in New York in the early 1970s. “It took a hellacious amount of [my] life . . . dangerous living to make it possible to write a ‘little’ play like R. J. Nobody who lay at home comfortable night after night with their head in a lover’s lap watching TV could have wrote that play.”5

Richmond Jim was successful but divisive. The Madness of Lady Bright had been around for ten years, but playwright and theatre critic Robert Chesley called Richmond Jim the first genuinely gay play because it was written primarily for particular kinds of city gay men. Critic Trebor D. in Portland made explicit the queer geography of Richmond Jim by pointing out to his readers that Jim is the boy from the small town and New York serves as “any large city with a developed gay community.” Jim comes to New York to learn what is not taught in the small town. Dick Hasbany in The Advocate called it “a mythic ritual initiation into a life fuller and more horrible than innocent . . . a resonant portrayal of growing up into an exciting world.” However, Neil Obstat in the San Francisco Sentinel wondered if the selection committee who chose the play as the Best Gay Play of 1979 “was limited to homophobes determined to use this piece as more slander against gay men. The political statement Richmond Jim implies is horrendous.”6

This critique of queer theatre was not new. At a time when the movement was battling negative stereotypes propagated by figures like Anita Bryant and the broader Moral Majority, some believed that theatre with insufficiently positive or politically unbeneficial themes harmed the movement. Mart Crowley’s 1969 Boys in the Band was lauded by some but also drew criticism for its stereotypes of gay men. In 1973, Martin Duberman wrote in a New York Times review of Al Carmines’s play The Faggot that “with friends like ‘The Faggot’ the gay movement needs no enemies.” The review contrasted The Faggot, which Duberman claimed used tired stereotypes for laughs, with Coming Out!, which used documentary evidence to claim national belonging for queer people. In Duberman’s estimation, Coming Out! served the movement by providing a historical basis for a modern identity and straight people a guide as to the necessity of the movement. Obstat’s review of Richmond Jim echoes this discourse of political utility. Of course, one can follow this discourse all the way to more recent debates over whether kink or nudity at Pride hurts or helps LGBTQ+ politics.7

These critiques stung Yeomans and seemed to change the trajectory of his art. Yeomans’s response to the critical reception of Richmond Jim was complex. On the one hand, he agreed that it was “an almost relentless descent into grimness. That’s the way living it was. The only mistake he [Obstat] makes is in assuming that my intention with JIM was to provide prurient titillation and endorse S&M. I think the metamorphosis in JIM (visually, if nothing else) is horrifying. I always thought that.” However, he wrote later of the “great puritanical backlash growing in the gay community itself as it is being forced to reassess some of its outrageously hedonistic excesses of the ’70s. Suddenly drugs, S&M, and macho chauvinism are rabidly inflammatory subjects in S.F. I think a lot of people would like to forget a lot of things were ever fashionable.” Reading his next show as a response to the critiques of Richmond Jim illuminates Yeomans’s critique of queer metronormativity. Yeomans’s characters were a little Southern Gothic, but they were also so close to the real people on which they were based that Yeomans worried about being sued. Two characters seem designed for derision and mocking but reading them all as the stereotyped tragic rural queer replicates the same metronormative stereotypes Yeomans wrote against. The characters in Sunsets are not in the dark of small-town closets as Jim was. They do not need to come out into the light as Jim did. Rather, Yeomans’s rural characters in their rural environment laid claim to queer kinship with, and belonging to, an imagined community that seemed to be excluding people like them.8

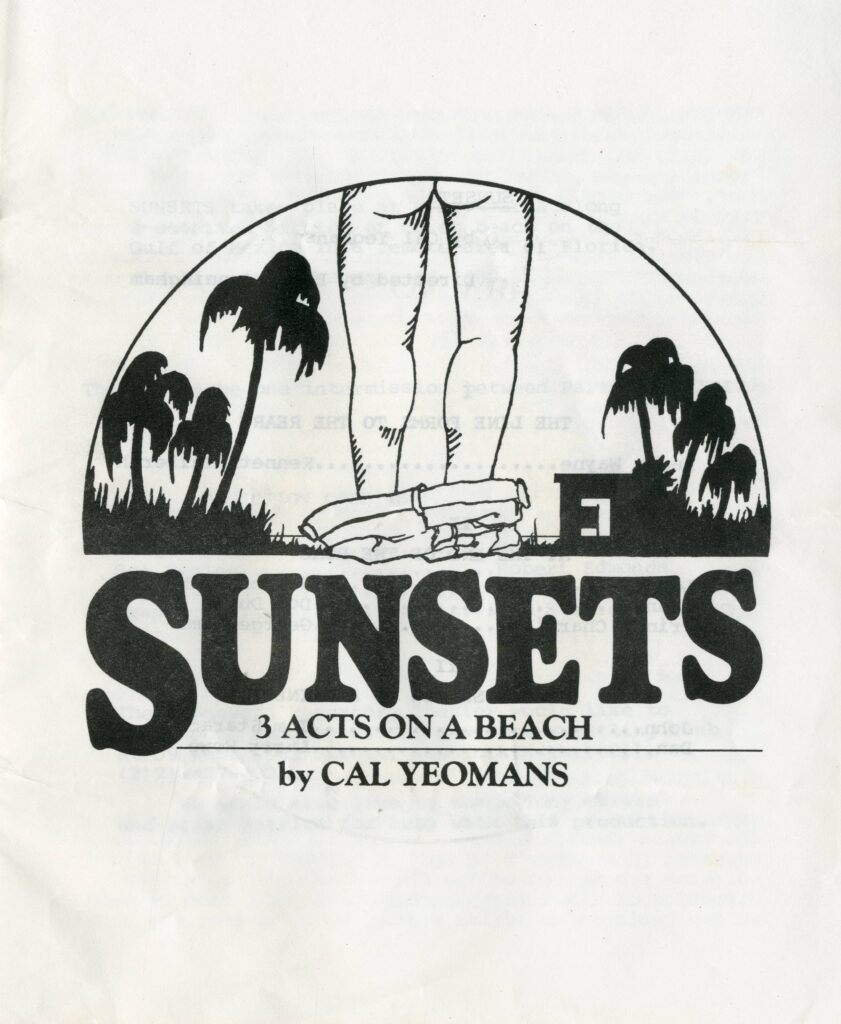

Sunsets: 3 Acts on a Beach

When Yeomans returned to live permanently in Florida in 1974, he began cruising at Fort Island Beach near his home. He was in a bit of a slump in 1980 as he grappled with the responses to Richmond Jim and what he saw as the state of urban queer politics now that he felt distant from aspects of metropolitan queer culture. “It was always difficult to write gay plays for gay theatre because the very nature of the genre is innately so controversial—even for gay people . . . I could go on writing hoked-up, half-assed situation soap operas, nice little plays about ‘me and my lover,’ and I’m sure these would be gobbled up as quickly as I could turn them out. This does not interest me, and it certainly does not excite me.” According to James Saslow at The Advocate, much of the gay theatre at that moment was of the “two-clones-are-clever-Village-or-Castro-roommates-and-have-zany-adventures-with-campy-dialogue genre.” Not all queer theatre was of this type, just as the lived experience of queer people differed from metronormative publications like The Advocate. However, the queer theatre landscape at that moment privileged metronormative or politically useful work. And it is against this that Yeomans was writing.9

Despite feeling distant and uninspired to write what urban audiences seemed to demand, Yeomans received recognition when Terry Helbing’s Directory of Gay Plays included his work, naming him as one of the gay playwrights to watch and conferring status on his body of work. Helbing was working diligently to legitimate queer theatre more generally. He wrote regular columns for Stonewall News, The Advocate, and the New York Native. His Gay Theatre Alliance was an international organization connecting playwrights with theatres and directors. The June 1980 Gay Theatre Alliance Newsletter reported that the Gay American Arts Festival included five plays, thirty-five short or feature-length films, and nine literary events. The newsletter further reported two new gay theatre companies in Chicago, one each in Rochester, Boston, Phoenix, Los Angeles, and two new companies in San Francisco in addition to Theatre Rhinoceros.10

In early 1980, Yeomans began crafting a character based on a series of conversations with a local man at Fort Island Beach. This was joined with two other acts to form a show that Yeomans believed would challenge metropolitan audiences. The set directions are simple: the outside of a public toilet, sand, palm trees, and a picnic table on a desolate stretch of beach. Yeomans could have set the show at any unnamed beach to universalize the appeal. Indeed, had Yeomans simply wanted to entertain audiences with southern stereotypes, a more general location would have been more suitable. However, he deliberately chose to set this show in the South, specifically on Florida’s Gulf Coast. By locating the show where he did, Yeomans conjured a little piece of the rural South for audiences in urban gay enclaves that was very different from the tropical paradise usually associated with the Atlantic side of The Sunshine State.

Sunsets: 3 Acts on a Beach began its life as a one-act performance called “The Line Forms to the Rear,” where Yeomans turned several real conversations into a monologue about “a poor little burnt-out former drag queen” who services men at a public toilet. It premiered at Theatre Rhinoceros in San Francisco. The Stonewall Rep in New York asked for a second and third act so they might have an entire evening. Yeomans drew upon the lives of two other real people who frequented Fort Island Beach to create a second act called “At the End of the Road.” And he used his own struggles with love and rurality as the basis for the third act, “In the Shadow of the Rainbow.” Together, they became Sunsets: 3 Acts on a Beach in the fall of 1981. The show traveled to the third annual National Gay Arts Festival in Chicago in 1982. It ran again at the 544 Natoma Gallery in San Francisco in September and October of 1982.11

Act I, “The Line Forms to the Rear,” is a monologue featuring Henry, a poor southerner with “the physical accoutrements of a burned-out construction worker, but the fingernails and walk of an off-duty drag queen.” Henry tells the audience that he used to do drag in Jacksonville. “I was a star for a while . . . They used to call me Henrietta Jayne. Maybe you’ve heard of me.” The script directs that a few bars of The Supremes’ “Stop! In the Name of Love” should be played for Henry to perform. However, the “music stops mid-gesture. A moment of emptiness grips the stage.” Henry tells the audience that he moved back to Springfield to settle down with a man that he loved. Domestic bliss was not all it was cracked up to be, as Herschel was abusive and left Henry for another young man. After recovering from a breakdown, Henry tried to return to Jacksonville and drag. Sadly, he was laughed off the stage and hopped the first Greyhound bus “to get out of that place. Well, after the bus got out of Jacksonville, I retired to the toilet and took off what I could of my make-up and put on pants and I been in them ever since and I don’t want no part no more of no kind of show bizness [sic].” More than showbusiness, Henry left behind the urban gay world that had rejected him. His mother welcomed him back to their mobile home, and he took up making hats out of beer cans until she suggested that he try to find people his age to spend time with.

His first attempts to find friends took him to K-Mart because it was air-conditioned. The passage of time is unclear in Henry’s monologue, but sometime later, there was an accident with a can of tuna while he was shopping for artificial flowers. The accident and another customer’s act of indecent exposure changed his life. “I been hit by a flying can of tuna fish, and that’s the straw that broke the camel’s back. I can’t take it no more. Can’t you see it’s my nerves? I can’t help it. I realized in a flash when I seen that old man’s schlong . . . it came to me clear. I don’t know how to explain it. But there’s a might lot of sufferin’ out there cause people can’t find nobody to touch ’em where they needs to be touched when they needs touchin’ and I just said to myself, I said, Henrietta Jayne, get out and do your part for the sufferin’ miserable and afflicted. Give all the pleasure you can and see what you get back in return.” After interpreting the customer’s indecent exposure as a lonely old man reaching out for affection, Henry spends his free time at the public toilet and services any man who wants it. Henry is very careful to point out that he was never one to engage in such sordid behavior before. “I am NOT your average run-of-the-mill common glory hole type harlot.” He is doing this as an act of service, not his own gratification. The scene ends with Henry telling the audience, “The line forms to the rear, honey. If you’re interested.”

Henry is funny and campy. He’s Southern Gothic and his story somewhat tragic. It would be easy to read him as a sad stereotype to be mocked, and some audiences likely took him that way. But Henry has a level of dignity in his work. Yeomans believed Henry to be his most searing challenge to the metropolitan gay audiences he imagines will see the show. In a letter from February 19, 1980, Yeomans wrote, “I finished a new play, and I’m right proud of it. I attack people and things I don’t like in my work these days and in two lines at the end, I managed to take on ALL upper east side snob fags and ALL S&M Leather fanciers and demolish both of them totally, just reduce them to a joke.” In a letter from March 1980, Yeomans clarifies who Henry is for and what he is trying to accomplish with the him.

The reason I wrote Henry was so that you urban gays would not forget that while you all are spending hard-earned cash-money buying your way into the lushly simulated confines (can you buy urine odor in a spray can yet?) of plushly air-conditioned, security guarded, completely authentically recreated TOILETS with padded, contoured, designer-created glory holes, that hundreds of thousands upon thousands of struggling, terminally oppressed rural gays still cannot BEG their way out of the real thing. We have no choice. I know you don’t like Henry. Nobody does. That’s the point; Henry has NO place to go. He cannot (as David Goodstein so glibly advised in a recent editorial) get out of Podunk on the next Greyhound bus. He couldn’t last 5 minutes in S.F. His I.Q. is probably 38; His education is somewhat lacking. His social retardation staggering. Nevertheless, he is a gay human being, and therefore, his needs need to be served.

Yeomans’s final line gets at the heart of Henry’s character. Henry is part of the larger gay community. He does not look or act like one of the privileged few who get to live out their days in San Francisco. Other letters from the period repeat Yeomans’s belief that queers on Castro Street ignored this kind of queer life and that life is not OK for the “vast silent majority of oppressed gays lurking hidden in the most unlikely places.” It is his hope that “the sufferings of these poor pitiful forgotten people will—when presented in that urban oil slick—take the hair off all those stoned eyeballs. I don’t know. I hope so.” Yeomans claims a place in “our world” and seems to imagine his audience as comprised of people who read David Goodstein’s editorial in The Advocate and glibly tell rural queers to just get on the next bus. Yeomans described Act II, “At the End of the Road,” as “a positively nauseous little tale of a sad couple’s pathetic little struggle to keep living with a modicum of ‘fun.’ Incredibly enough, it is all true. It is based on a reality that I’ve observed for many months now.” This husband-wife team visits the beach where Manny seduces men in the toilets, ostensibly for his wife Leona to service in their car. But it never seems to work out that way for Leona. The scene takes place on the couple’s anniversary. Leona has begged Manny to stay home and play in her new lingerie, but he has dragged them to the beach. An attractive man enters the toilet building. The conversation is broadcast to the audience while Leona continues her monologue, lamenting her lot in life. The man, a character simply called Prince Charming in the script, orgasms just as Leona tells the audience she thinks of “all the babies that will never be.” And he leaves only to disappoint Leona, who looks expectantly after him. These characters seem the most open to reading as comic relief for queer audiences. If this was Yeomans’s intention, it backfired since the act seemed to arouse the most disgust, according to critics. It does serve to foreshadow a character for the third act while poking fun at a man in the closet and his clueless wife.12

Act III, “In the Shadow of a Rainbow,” is the most directly autobiographical. The title establishes a conflicted relationship with “a rainbow,” which had only recently been adopted as a gay symbol and was not universally accepted. “In the shadow of” is not antagonistic to the rainbow but rather a recognition that it is a symbol and rallying banner for queer culture. The queer experience symbolized by the rainbow overshadows the queer experience of those Yeomans is dramatizing. Unlike Henry, who was funny, or Manny and Leona, who were tragic, the mood of this act is poignant. It is made all the more so when read in the context of his letters because he claims it was about himself and a man he knew. It was all of the things left unsaid between them. If Henry was a campy challenge to metronormativity, “In the Shadow of a Rainbow” seemed designed to pull at audiences’ heartstrings.

The script calls for John, “a good-looking man in his late 30s or early 40s,” and Dan, “a good-looking man in his mid-20s,” who is played by the same actor as “Prince Charming” from Act Two. John appears first. The stage directions indicate that when he walks on stage, “it is the awareness of the audience that has caused him to stop. He lowers his head with a certain fatigue and rubs the back of his neck. Suddenly he raises his face to the audience, confronting it directly.” John tells the audience that he comes to the public toilet because of a specific man but then gets to the heart of his character. The pauses and ellipses in the script indicate that John should be struggling to put words to feelings. “There’s nowhere else to go. And then . . . I’m afraid. Afraid that if I stay back there where . . . there’s too many of . . . afraid that if I stay there too long without something of anything else that . . . Afraid I’ll forget. . . forget how to touch, how to reach out, how to reach out for touch . . .” John spends a few lines discussing dating via a baseball metaphor. And he ends his monologue saying, “suffice the world of you is far away, far, far, away. I’m here.” These lines, delivered to the audience, address the conflict between the playwright and his region. Without the critical mass of the gay community, might John (Yeomans) forget how to find love? John is torn between their world and his own.

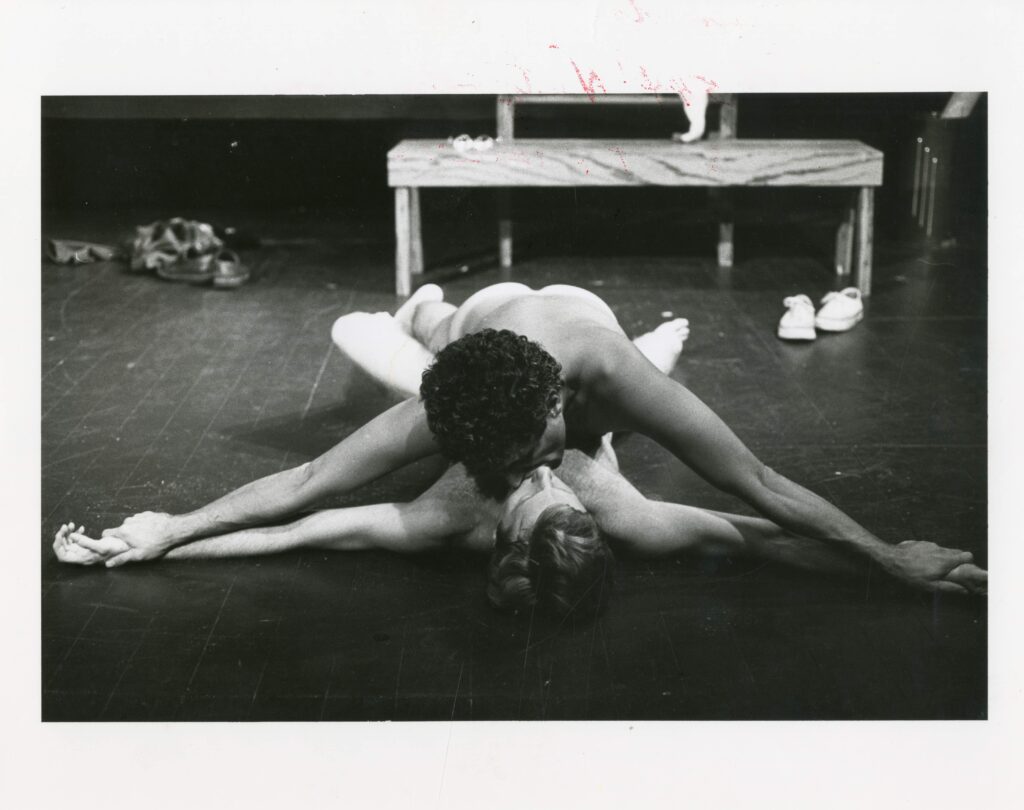

Their initial exchanges are awkward as both men dance around Dan’s mask of heterosexuality. They go home to fumble through conversation before electrifying oral sex, resulting “in the most unified kind of communication in that kind of moment I’ve ever experienced.” The rest of the act demonstrates a growing attraction and Dan’s growing acceptance that he may not be completely straight. The scene ends with a naked wrestling match and a kiss in John’s living room. Despite Dan’s protestations that “men don’t kiss,” Yeomans’s directions state that the match should be a carefully choreographed “struggle for the truth . . . Finally John subdues Dan and, despite his struggle, manages to kiss him for quite a long time, during which Dan’s struggle against John’s affection weakens until, finally, Dan gives in to John and starts passionately kissing him in return.” In that act of returning the kiss, there seems to be a shift in Dan. Perhaps men do kiss, and their perception of their masculinity can shift. This is all the audience is given. There is no coming out. There is only the returned kiss and blackout.

Critical response to the play was generally positive, and most critics seemed to understand what Yeomans was trying to do. Playwright and theatre critic Robert Chesley’s review in New York Native is the most illustrative. He wrote that audiences were visibly disturbed (by Leona’s character given her discussion of numerous abortions and a complaint about seagull poop landing in her crotch) but that “the play takes two major steps that I strongly feel are necessary for gay theatre . . . It deals with working-class people and middle America rather than middle- or upper-class gay men in the ghettos or gay resorts; and because it deals bluntly and honestly with sex . . . It is concerned with what really happens between real people; it jogs us out of our cozy, complacent ghetto reveries and reminds us that gay liberation is more than a matter of fun shops, fun discos, fun drugs, fun restaurants, and fun sex.” Yeomans agreed with Chesley. He wrote to a friend that the show was not “dreary politically correct predigested sitcom Pablum for the masses with a swinging disco beat in the background. Everything is NOT alright and good about our world as we live it and I don’t try to pretend that it is.” If, as Chesley and Saslow contend, the majority or most successful works were metronormative depictions of gay life, the queers of Sunsets were a direct challenge to that. The little piece of the South that Yeomans conjured on stage confronted audiences with the reality of lives beyond the ghetto. If the author and critics are to be believed, he reminded audiences that the struggle must continue. Queer liberation must be more than capitalist consumption. It must be more than the idealized life of attractive white gay men to whom, according to Chesley, queer theatre had so far been directed. Despite some critics understanding what Yeomans was trying to do, the show never made it into the queer canon. Most audiences did not seem interested in Henry, John, Dan, Manny, and Leona’s plight. Yeomans might have wanted to shake people out of their cozy ghetto reveries, but the show premiered at the worst possible time. Its message was quickly overshadowed by the AIDS crisis.13

Though what would later be called AIDS had been circulating in the United States since at least the late 1960s, it did not become “the AIDS crisis” as we know it until the summer of 1981. Theatre artists responded as the death toll rose rapidly and queer communities scrambled to make sense of the epidemic. Jeff Hagedorn’s One (1983), Robert Chesley’s Night Sweat (1984), and Rebecca Ranson’s Warren (1984) were the earliest theatrical works to grapple with AIDS. Much like Yeomans’s characters, Ranson’s Warren was a southerner. But he left the South and died of AIDS-related complications in San Francisco in April 1984. The profound destruction of the AIDS crisis and the immediate necessity of responses seemed to leave no room for people to deal with someone like Henry. Yeomans wrote in 1986 that he had several unfinished scripts meant to follow up on Sunsets’ “sexual performance theatre. Needless to say, these can’t now be produced as originally conceived in our time or in the conceivable future. What was exciting, hot, sexually electric yesterday is now either fatuous or unmistakably ghoulish. Jokes that were funny are now horrifying or, at best, tasteless.” Oral sex became one of the pillars of safer sex discourses, but Henry reveled in it with an abandon that was unseemly in the early years of the crisis.

Yeomans reflected on queer theatre in a letter to Robert Massa at the Village Voice in 1986 and remained deeply committed to the transformative power of art: “It is time to speak. To speak anything you can. To speak as much as we can. To say all we can. To let everyone know all they can of our experience—of the right side of it, of the wrong side of it, of the goodness of it, the badness of it. We must let the world see the full range of our experience, the full range of our struggle and certainly the full range of our suffering and despair.” Yeomans left a powerful legacy. After Sunsets, he worked primarily in photography and poetry. He teamed up with other southerners, such as Ernest Mickler, to show a rustic southern culture to other parts of the country. Because of his family’s wealth, he established several endowment funds at the University of Florida in Gainesville, including The Lee C. Yeomans Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Fellowship in the Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences (IFAS), The Vada Allen Yeomans Professorship in Women’s Studies at the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and The Calvin Yeomans Special Collections Enrichment Fund for the George A. Smathers Libraries. He died of heart failure in October 2001.14

Sunsets was staged again in Chicago in 2024, this time without Manny and Leona. The reviews were generally positive. Chicago-based theatre critic Brian Kirst wrote that “the nudity and Yeoman’s sexually accentuated dialogue do seem to harken back to the ‘hear me roar’ days of the piece’s genesis. But they find timely resonance in this production as well. Our rights and lives are still being threatened on a daily basis. There is no time like the present, highlighted by the veils of our past, to expose our truest selves.” Sunsets documented and critiqued the privilege of outness, the characters pushed for a more expansive queer kinship. Let us not now retreat to reveries of fun shops and fun discos.15

Jay Watkins is a historian of the queer South. His first book, Queering the Redneck Riviera: Sexuality and the Rise of Florida, examined the intersections of midcentury capitalism and queer placemaking to return queer people to North Florida’s history. Since 2016, Watkins has taught history at the College of William & Mary.

NOTES

- Journals, Cal Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Boxes 21-22, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

- Cal Yeomans journals; Cal Yeomans journals.

- Jeffrey Escoffier, “The Political Economy of the Closet: Notes Toward an Economic History of Gay and Lesbian Life before Stonewall,” in Homo Economics: Capitalism, Community, and Gay Life, ed. Amy Gluckman and Betsy Reed (Routledge, 1997), 123–134; Edmund White, States of Desire: Travels in Gay America (Plume, 1991), 37; Gayle S. Rubin, “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality,” in Culture, Society, and Sexuality, A Reader, 2nd edition, ed. Richard Parker and Peter Aggleton (Routledge, 2003), 150–187; Scott Herring, Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism, (New York University Press, 2010).

- Quoted in Robert Schanke, Queer Theatre and the Legacy of Cal Yeomans (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 85; Schanke, 85.

- Cal Yeomans, Richmond Jim, 1977. The Southeastern Arts, Media, and Education Project, Box 3, Folder 7, COLL 2008-020. One National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Los Angeles, CA ; Yeomans, Richmond Jim; Cal Yeomans, letter to Tom, March 13, 1980. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 31.

- Robert Chesley, “Review: Who Took Richmond?,” The Advocate, June 28, 1979. The Southeastern Arts, Media, and Education Project, Box 3, Folder 7, COLL 2008-020. One National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Los Angeles, CA; Trebor D., “Entertainment,” no date, unattributed clipping. Yeomans collection, MS 261, Box 6; Dick Hasbany, “Revelations: Wanted or Not,” The Advocate, June 24, 1982, 51. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 6; Neal Obstat Jr., “One Win, Two Losses at Theatre Rhinoceros,” San Francisco Sentinel, May 16, 1980. Cal Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 6.

- Martin Duberman, “The Gay Life: Cartoon vs. Reality,” New York Times, July 22, 1973, 89

- Cal Yeomans, letter to Fred, April 22, 1980. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 31; Yeomans letter to Fred, April 22, 1980.

- Schanke, Queer Theatre, 147; Quoted in Schanke, Queer Theatre, 113.

- Gay Theatre Alliance Newsletter, June 1980, Vol. Two, Issue One, 1. Gale Archives of Sexuality and Gender.

- Cal Yeomans, The Line Forms to the Rear, 1980. Scripts (gay and lesbian drama) Collection, Coll 2008.003, Box 9, Folder 2. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Los Angeles, California.

- “Fred” letter to Yeomans, February 19, 1980. Cal Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 31; Yeomans, letter, March 24, 1980. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 32; Yeomans, letter, July 12, 1980. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 32; Yeomans, unaddressed letter, December 2, 1980. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 32; Yeomans, unaddressed copy of letter, November 1, 1980. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 32.

- Robert Chesley, “Taxi Zum Closet,” New York Native, October 19–November 1, 1981, 31. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 7, Folder 6; Yeomans, unaddressed letter, December 2, 1980. Yeomans Collection, MS 261, Box 32.

- Schanke, Queer Theatre, 147; Michael Adno, “The Short and Brilliant Life of Ernest Matthew Mickler,” Bitter Southerner, https://bittersoutherner.com/the-short-and-brilliant-life-of-ernest-matthew-mickler.

- Brian Kirst, “Nostalgic ‘Sunsets’ still offers a timely reflection of LGBTQ+ community,” Windy City Times, February 7, 2024.