Oakland-born artist Adrian L. Burrell is a light worker. Using lens-based media that require light to function (primarily photography and film), the artist has traversed various “Souths”—from the local to the global, including Louisiana, Mississippi, Nicaragua, Brazil, Nigeria, Senegal, and South Africa—to spotlight instances of struggle and self-determination. Burrell’s family history, along with his own encounters with state-sanctioned violence and the impacts of incarceration, inform his art. The majority of the artist’s ancestors were enslaved Africans and sharecroppers, and everyone in his family, except his sister, has been incarcerated or had confrontations with the state. Through his unique mode of visual storytelling, he excavates and fabulates his family’s ongoing search for abolition and liberation across generations and geographies. This history, which Burrell can trace back to the 1760s, is a microcosm of African American life—a compendium of past, present, and future practices of reckoning and refusal that Black subjects have employed, and continue to use in the afterlife of slavery.

Burrell’s play with nonlinear narratives and his dynamic editing choices create various states of suspense and suspension, mirroring the artist’s central preoccupation: is redress possible in an anti-Black world? To answer this question, Burrell draws on core concepts of contemporary Black radical thought—what scholars Robin D. G. Kelley and Christina Sharpe have respectively called “freedom dreams” and “wake work”—as well as Afrofuturism’s Black Angel of History as a symbol of Pan-African liberation and survival. His early projects led him to Mississippi and around the globe to document the grassroots movement traditions of women-led collectives. His most recent work explores the power of still and moving images as sites for structural change and Black communal healing. Mama’s Babies (2013–ongoing), a series of multimedia installations, follows the journey of his ancestors through antebellum and postbellum slavery in the Deep South, the Great Migration, the crack era, and into the contemporary moment, which is marked by another form of displacement: gentrification. Alternately, The Dandelions (2020) is a meditation on the limits and possibilities of Black radical imagining. The protagonist of the film, a Black freedom fighter, sends a message to the past about the path to liberation after crash landing in the future.1

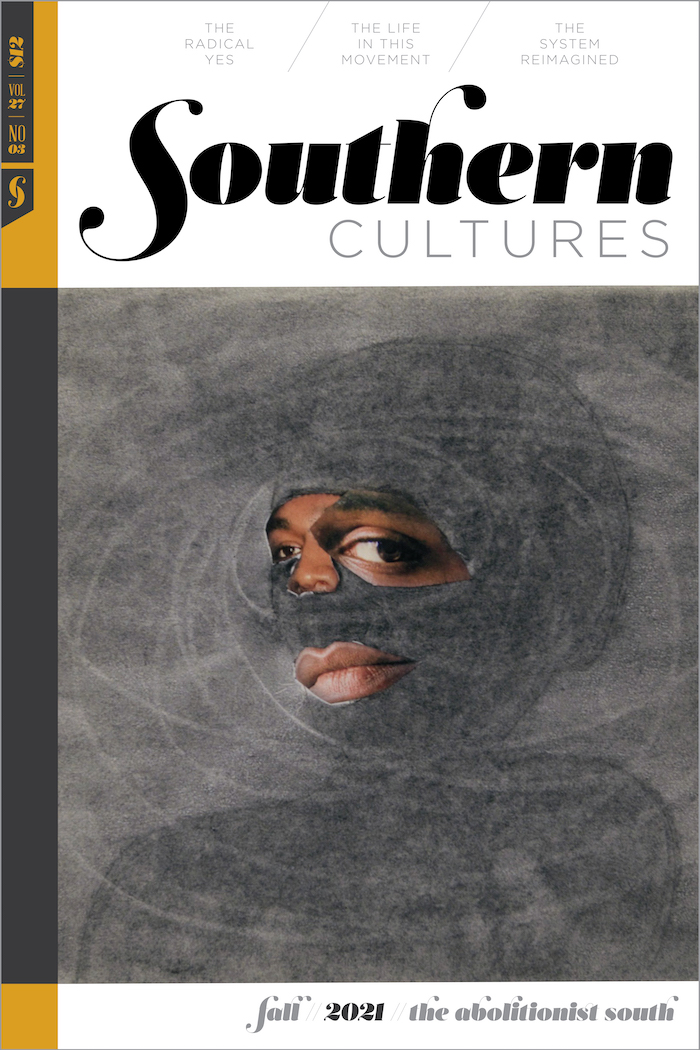

Building on these bodies of work, the nonlinear series of images and text on the following pages question where and how we imagine and dwell in abolition. Spanning time and location, the real and the speculative, “Looking for Abolition” focuses on the space between place and belonging. A thicket of trees camouflages a dilapidated mill house set on former plantation land. An unnamed child turns his face toward fireworks that illuminate the night sky, an image that brings to mind both Fourth of July celebrations as well as deferred dreams of freedom and belonging. The piercing gaze of a Black woman, Stephon Clark’s grandmother, pricks viewers as her eyes cut across and through calls to amend California’s laws on the use of excessive force. Surrounded by protest signs and banners, she is part of a kinship network bound by loss that she did not choose as she labors to realize a more just world in the wake of her grandson’s stolen life. These are the branches of an unwanted family tree. These are the extensions of an American South that has long envisioned a world without policing, prisons, or other forms of punishment.

Another grandmother, the artist’s muse, pens a letter to the future weeks before her passing, while a mother writing in the now reminds us that we all we got and “God Don’t Like Ugly.” Next, Burrell captures himself in a moment of reprieve in an unlikely setting. In his version of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce’s modernist novel about an artist’s maturation, Burrell rejects the sensationalized violences that have become part of everyday Black life. As he reclines in a small blue swimming pool, his limbs spill over the pool’s edges. He is excessive, a mixture of legacy and leisure amid a sea of shipping containers. He cannot be contained. Yet he is surrounded, confined. At once arresting, fantastic, and mundane, Looking for Abolition is a complex picture of Black American life under and against structures of containment that expands our view of the abolitionist South, from the slave hold to Louisiana to Oakland and beyond.

The

House

That

Abolition

Built?

What, to a young Black boy, is the Fourth of July?

Dear Future,

My name is Threater Lewis.

I was born in Minden, LA, on August 16, 1927.

I gave birth to 16 children.

I raised 12, and I have 100s [of] descendants.

I enjoyed them; I had some good and bad days but I love them all.

I had some bad times. I lost my husband, their father, who left me widowed with 12 children.

I met my new husband who helped me to raise them. He was good [to] me, the love [was] just

like their real father.

Everything’s all right, by the good of the Lord. I trust in home.

I wonder [when] the future comes, what it’s gone be like.

Dear Now,

Life has many choices, lessons, and reasons. Money will never solve your real problems so pace yourself.

We come from a long line of folks who said, “Keep on keeping on.” They dreamed us up from nothing. They dreamed us, and now we here. How big did they dream? What will we dream? That’s legacy.

We all give small parts of ourselves to the next generation. We will always be bigger than you and I, and us as a group will always get more done than when we are apart.

So be good, stick together, dream well, and pass it on.

With Love,

Vanessa Burrell

What, to a young Black man, is FREEDOM?

This essay first appeared in the Abolitionist South Issue (vol. 27, no. 3: Fall 2021).

Tiffany E. Barber is a scholar, curator, and critic of twentieth- and twenty-first-century visual art, new media, and performance. Her work, which spans abstraction, Afrofuturism, dance, fashion, feminism, and the ethics of representation and aesthetic criticism, focuses on artists of the Black diaspora working in the United States and the broader Atlantic world. She is assistant professor of Africana studies and art history at the University of Delaware.

Adrian L. Burrell is an artist from Oakland, California. His work focuses on notions of kinship, diasporic narratives, and the gaps between place and belonging. Adrian is a YBCA Creative Fellow and received his BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute before getting his MFA from Stanford’s School of Art and Art History.NOTES

- As Reynaldo Anderson and Tiffany E. Barber explain, the Black Angel of History reorients and reconceives Pan-African liberation and survival in the face of international fascism, mass death and racial capitalism, climate change, and other crises to come. See Tiffany E. Barber and Reynaldo Anderson, “The Black Angel of History and the Age of Necrocapitalism,” Terremoto, November 6, 2020, https://terremoto.mx/en/revista/the-black-angel-of-history-and-the-age-of-necrocapitalism/.