As part of Reckoning and Resilience: North Carolina Art Now, the Nasher Museum of Art recorded a conversation between artist Clarence Heyward, whose paintings are part of the show, and Tatiana McInnis, who teaches American Studies and Humanities at the North Carolina School of Science and Math in Durham, NC. This conversation has been edited and condensed for publication. To hear the conversation in full, listen to the Nasher Museum Podcast. Reckoning and Resilience is on view through July 10, 2022.

Tatiana McInnis: Tell us a little bit about your journey to becoming an artist.

Clarence Heyward: It’s a pretty long journey. I’ll try to sum it up. So, I grew up going to museums and art shows and stuff and I also was in art schools as a young kid. I went to art programs. So that led me to actually majoring in art education in college because I always heard that if you were an artist, you had to teach to make money, because, you know, most artists were starving. But during my student teaching, my last year of college, they told us what the salary was for a teacher, which was $25,000, [actually] $25,252. I should get that tattooed on me because I always will remember that number. It changed my life forever.

Man, you can’t continue to go on like this. You need to be an artist.

When they told me that, I said, “There’s no way I’m doing this.” So I actually ended up being a truck driver for, like, 10 years, and then I got tired of that, so I moved into the management side, logistical side of truck driving. I did that for two-and-a-half years and it drove me crazy. And part of that reason is I moved to Clayton [North Carolina]. Long ride, lot of car time to myself, and I thought, “I can’t do this the rest of my life.” Actually, it was my wife who motivated me and pushed me into being an artist. We went to high school together, School of the Arts in New York, and so she knew, you know, I had talent. And over the years, I did things here and there and she said, “Man, you can’t continue to go on like this. You need to be an artist.” I don’t know where that was coming from because, you know, we never talked about me being an artist. But we had the conversation and she said, “OK, I’ll give you a year to get yourself together. And then you’re going to be an artist.” For some reason, I took it seriously. So, over that year, I would stay up at night, painting and drawing and just going to talk to other artists. I went to a bunch of workshops, I was just doing everything I thought I would need to be an artist. So, a year to that day, I don’t know if she set it on her calendar or what, she said, “It’s been a year.” You know, “What are you doing?” And I was just like, “Well, you know, we talked about it, but I didn’t really save, I’m not prepared for this.” And when she handed me my resignation letter, I’ll never forget it, I was just like, “OK, she’s serious.” So, I went to work.

TM: Wait, she drafted your resignation letter?

CH: She wrote it up for me. I didn’t even know she was doing it. Funny enough, we had a manager’s meeting at work that same day, and I was super stressed out and you know how you want to tell your boss something but you can’t? But I had the letter in my pocket. So after a while, I stopped the meeting in front of everybody. It was super dramatic. If I ever get famous, they’re gonna make a movie about it, because it was super dramatic. I stopped and I said, “Hey guys, you know what, stop the meeting, stop the meeting. I can’t take this anymore.” And everybody was looking at me like I was crazy. And I pulled out the letter, and I felt so relieved because, you know, I’m like, “I don’t have to take this, here you go.” It was a shock and everything. But when I got to the car, I cried. I cried in the car because I had no idea what I was doing.

TM: It’s that adrenaline and then the crash after. Like, in the walk from the car, or walk to the car.

CH: Yeah, like, “Oh, my God, what did I just do? How am I going to pay my bills?” But that’s how it started. After I left my job, luckily, I had a lot of vacation time saved up, because I was the employee who never took off, so I had a little bit of a cushion. But after that, man, I just started applying to shows everywhere. Anybody who would pay my work any attention, I would just get it in front of them. And that was about four years ago and I’m here now.

TM: I have two follow-up questions. Would you ever consider going back into teaching or trying to teach again? The salaries look a little bit better. Not much better, but a little bit better.

CH: No. Actually, I think being an artist, it probably solidified the fact that I’ll never teach. One, I make more now than I did when I was working. And two, I get to go into places now and do workshops and things like that, and I like that a lot better. I don’t have to plan out a year or activities. I can go in and say, “Hey, this is what I do and we can figure out something around what I do.” And, you know, I feel like I get a little more respect than the actual teacher because I’m the guest. So, you know, they’re always happy to see me. My wife’s a teacher, so I know how it goes. When it’s the same teacher every day, it’s like, “Oh you again.” But when I come in, it’s special. So I’m like, “I’m here!”

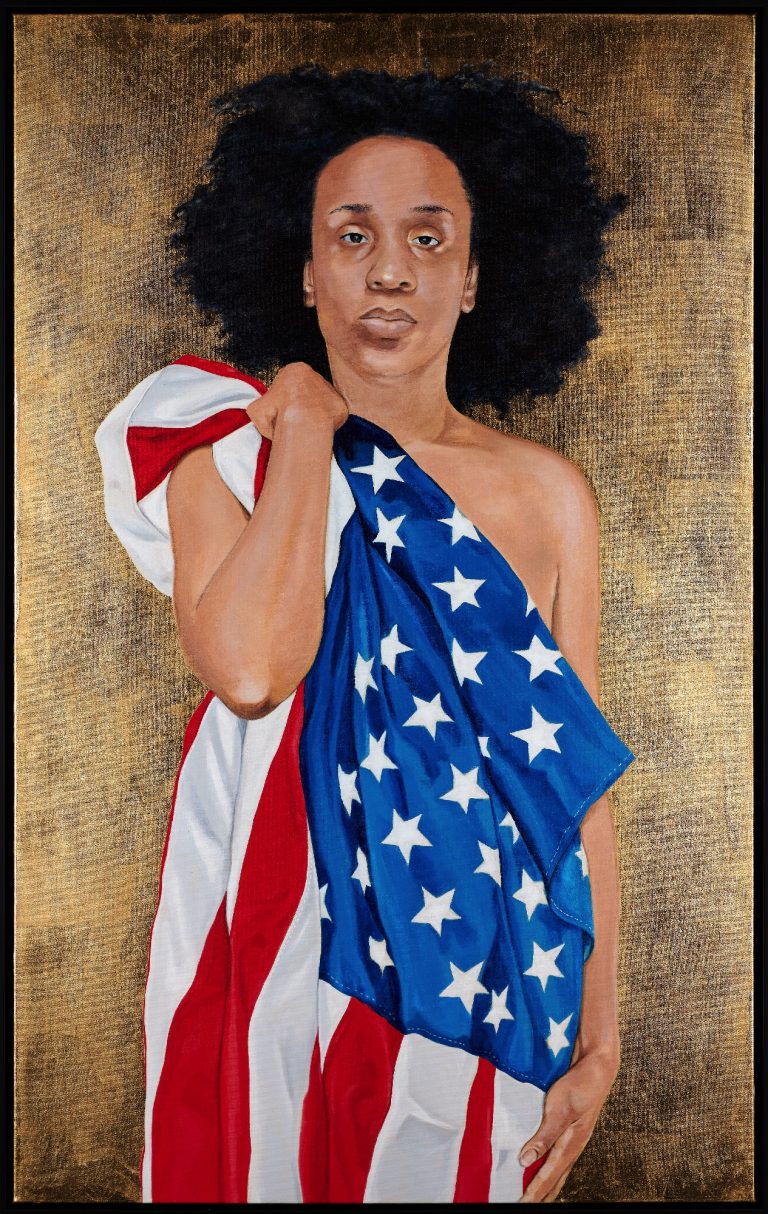

TM: Yeah, I’m gonna have to use you strategically and have you come in and do a guest lecture in my classes. We just got a plan for it, so we can conjure up that respect. But yeah, absolutely. I think my second follow-up question, because you’ve spoken so much about your wife and her inspiration, and we talked a little bit about your piece in Reckoning and Resilience, the Liberty Enlightening the World piece. And so maybe if I could hear a little bit more about the inspiration behind that piece and especially as it relates to that story of your wife motivating you to do the big gesture of quitting your job, at a meeting no less, which is fantastic.

CH: That’s actually a portrait of my wife, Liberty Enlightening the World. I guess now that I think about it, it’s like more of a tribute, right? Because the Statue of Liberty is a beacon of hope and she’s kind of like my beacon of hope. But I made that work for an exhibition I had called the Symphonies of Silence, where I was exploring what it means for me to be African American, and I was searching for my roots and trying to find a connection between Africa and America. When I was doing that, the Statue of Liberty kept coming up, because, you know, immigrants coming into the city and all that stuff. So, I just decided to reimagine the Statue of Liberty with my beacon of hope, which is my wife.

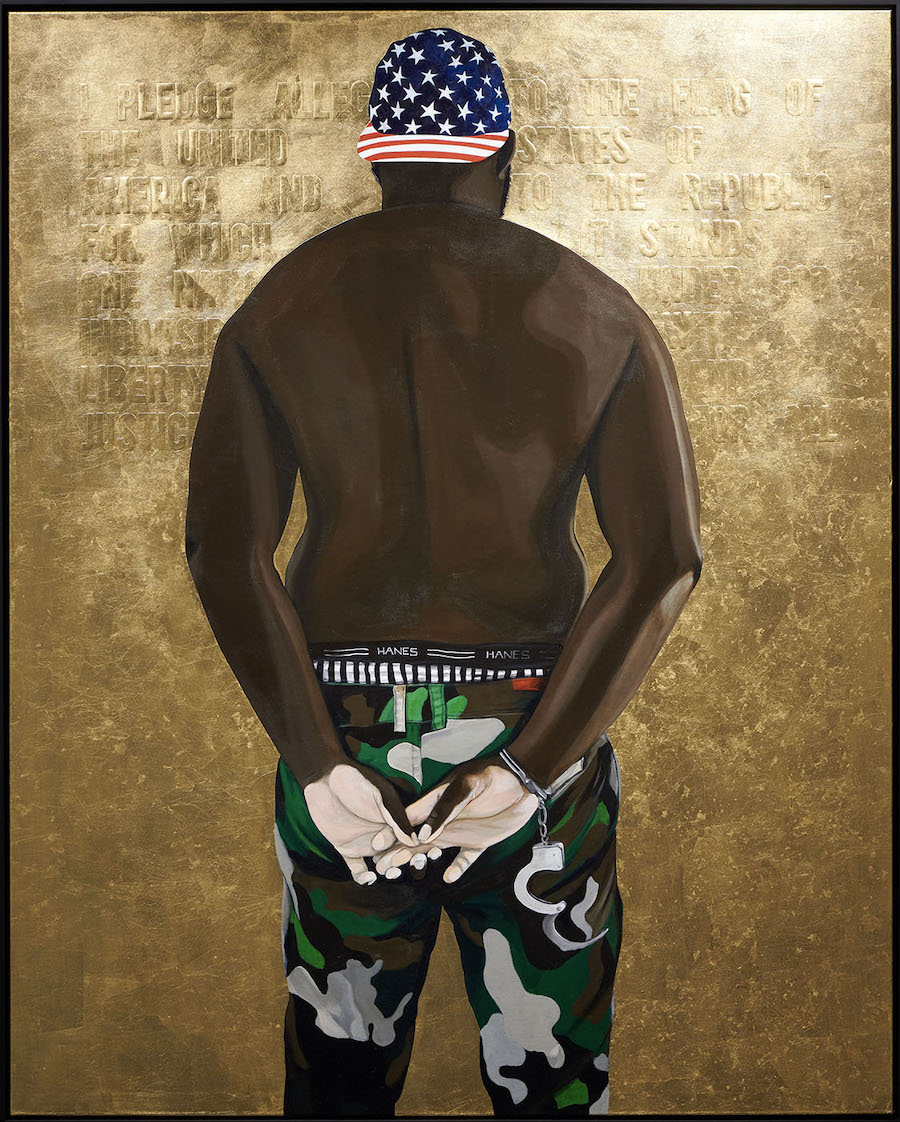

TM: Yeah, what about the other piece that is in the exhibit, the PTSD piece. How is that similar or different from the tribute to your wife?

CH: PTSD is more of a self-reflection. I made that piece right after seeing the George Floyd situation, and I started to imagine myself and what America means to me and my upbringing and how I was raised. I kept going back to elementary school, when we had to stand up and say the Pledge of Allegiance every day. And I started examining it as an adult and I realized that pledge doesn’t really apply to me. I was kind of indoctrinated to say it when I was younger. It’s like riding a bike at this point, you’ll never forget it. But you never were taught to question why we were reading it or what it means to you. So as an adult, while I was revisiting all these ideas, it just didn’t sit right with me anymore. And it was just like, “Well, what can I say about it?” And as an artist, that’s kind of what I do, right? If I have a problem or I’m trying to figure things out, I make work about it. And I came up with that composition.

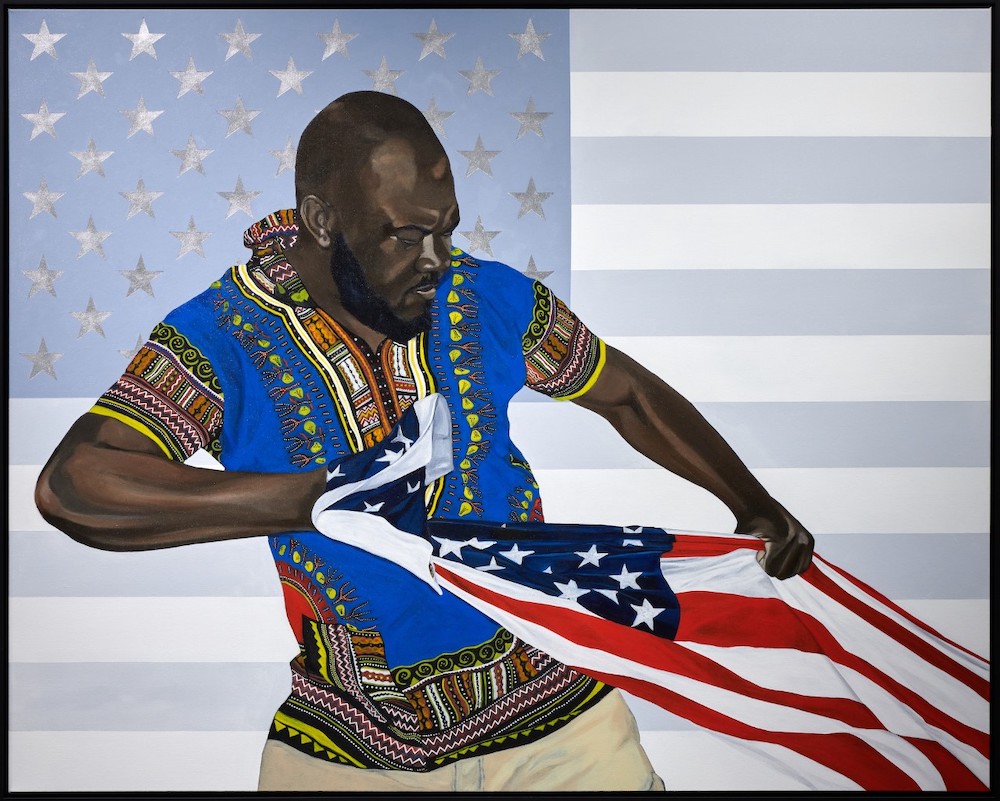

TM: That’s right. One thing I’ve been thinking about, really throughout my teaching generally, is how we, as Black people, and myself, especially, as a Black educator, what’s the way to represent history that accounts for these absences? So the Pledge of Allegiance, but I’m not in it. The American flag, but I’m not in it. And I’m curious if you can say a little bit more about how these pieces or how your work in general tells a version of American history.

CH: I’ll say the work that I make today will be American history in the future. I’m basically documenting my experience as an American now. The stories are current and present, but in 20, 30 years, my children will be able to go to the museum and they’ll remember these times, but my grandkids, who haven’t experienced this, these are all lessons to them, right? They [won’t] have to look in the history books per se, they can go to the museum and, hopefully, my paintings tell the stories that will be in the books by the time my grandkids are able to study.

TM: Yeah, what are some lessons that you would want to impart to your children, but especially to grandchildren and thinking of future generations? If you were to put language to your artwork, what’s the lesson that you would like them to take away?

CH: That’s a good question. A couple things. I want them to know anything is possible, right? Because, to be honest, I don’t know how I got here. But I’m here. But then I would want them to know that they belong exactly where they are. I had this thing of imposter syndrome as far as when my artwork started taking off. And I was like, “Man, how am I here? Why am I here?” But I think the fact of the matter is I’m here because I’m supposed to be here, right? My story connects with people in a way that has gotten me to where I am. And I want them to understand that. Just tell your truth, tell your story. And if you really want to do it, just do it. And you will end up exactly where you’re supposed to be.

I’m here because I’m supposed to be here, right? My story connects with people in a way that has gotten me to where I am. And I want them to understand that. Just tell your truth, tell your story.

TM: I feel like another lesson is to quit your job. I wish someone had told me that—at least once, like not all the time, right, don’t make a habit of it. But I do think there is something to be said about what you learned from quitting a job that’s not serving you.

CH: I teach my children—well, it’s going to sound horrible—but I teach them that a job is not necessary, right? Like my oldest, she likes to cook, so she says she wants to be a chef. But then sometimes she wants to be a dancer. So I’m like, well, what would that look like? How would you make money? I’m not saying go get a job as a dancer, I’m saying if you want to dance, how could you use dance to live the life you want to live? So it’s not even about money, right? It’s about being able to live the life you want to live. I would paint if I didn’t make any money, right? As long as I could support my family in the way I need to. If I had to stand out on a corner and make and sell my paintings, that would be, you know, just as good as what I’m doing now as long as I get to support my family.

TM: Yeah.

CH: So it’s all about just—it sounds cliche—but really being happy. You know, just do what you love and the rest really will work itself out.

TM: I’m thinking about my students and the things I want them to know about the world as they sort of enter into it, especially, you know, after George Floyd, in the midst of a pandemic. A lot of what I’ve turned to in my teaching has been visual art. I’m always really fascinated about my students kind of looking at art pieces and coming away with completely different interpretations than I might have or that, you know, anyone listening to this might have. And I’m curious, speaking to you as an artist and as someone who is bringing so much passion to your work, how do you feel about those different interpretations that circulate around your work? And maybe even going further, how does that relate to Blackness and how we perceive Blackness and Black artists?

CH: I feel so many ways about that because sometimes people’s opinions can pigeonhole you, too, right? Like, sometimes I’m simply painting something because it’s a story. It might not have anything to do with it being political or trying to make a statement. OK, today my daughters made me pancakes for breakfast, right? I might make a painting about how that made me feel or the fact that they made me pancakes for breakfast. In my opinion, there’s nothing political about that. But because of a lot of the paintings I’ve done in the past, people will see that work and, I mean, sometimes they dissect it to the point where it’s laughable, right? The pancakes, I don’t know, were originated by Black children. They’ll break it down to the point where I’m taking notes, at this point, on my own painting. So that part to me—sometimes it’s cool because sometimes it gives me different perspectives for an artist’s talk or a statement or something. But then I also like hearing different people’s point of views because everybody’s looking at it from their perspective, too. To be honest, I don’t really have the answers in my work. The work kind of just poses a lot of questions and depending on your experience is how you see it.

TM: Yeah, can you say more about the pigeonholing that either you experience or other Black artists experience, and what are maybe some of the consequences of that?

CH: Well, in a way, I get pigeonholed because people think all the work I make is political. But that’s in part due to the fact that a Black body on a canvas is political, right? It’s fairly new and it’s not something that’s super common. It’s cool to be a Black artist now, but ten years ago, it really wasn’t, right?

At this point, I don’t think I can paint something that doesn’t mean anything to me. I can’t just paint a rose because it’s a rose. I’m always going to have some kind of meaning on what I’m doing. But I kind of want to define that meaning, I don’t want people to define it for me. It’s difficult because you want to leave things open enough for people to have their own interpretations, but then, for the most part, you’re actually making this work for a reason.

I get pigeonholed because people think all the work I make is political. But that’s in part due to the fact that a Black body on a canvas is political, right?

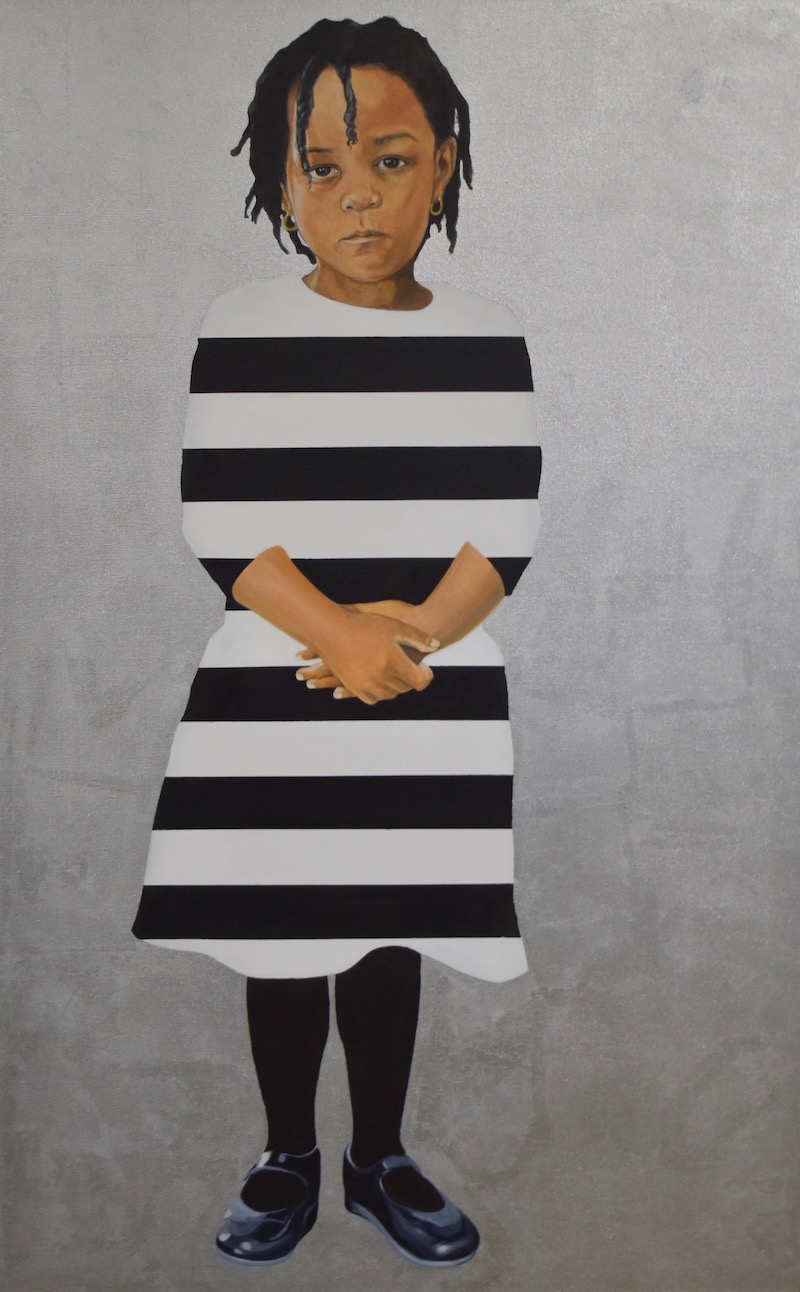

I’ll talk about one painting in particular: the painting I made called Second Child. That painting really was speaking to the difficulties I was having with my second child. We had our first and we thought we had it figured out. And then my second one came along and she’s super rambunctious, the exact opposite of my oldest daughter, so I made a painting about it. And at the reception, you know, I had so many people coming up to me because she has black and white stripes on her dress. They started talking to me about the history of child imprisonment and stuff that I had no idea what they were talking about. And I was like, no, it’s just about my baby girl. So, I mean, I get a lot of stuff like that. So the pieces I have in the show, it’s me in handcuffs, so it’s political, right? Pledge of Allegiance, that kind of stuff. It’s kind of obvious, actually. But some of the other ones that I think I’m doing something simple and it’s not political, because people have experienced other works from me, they always tie it back to that.

TM: What’s on your mind now? What’s maybe an image or lyric or something that’s on your mind?

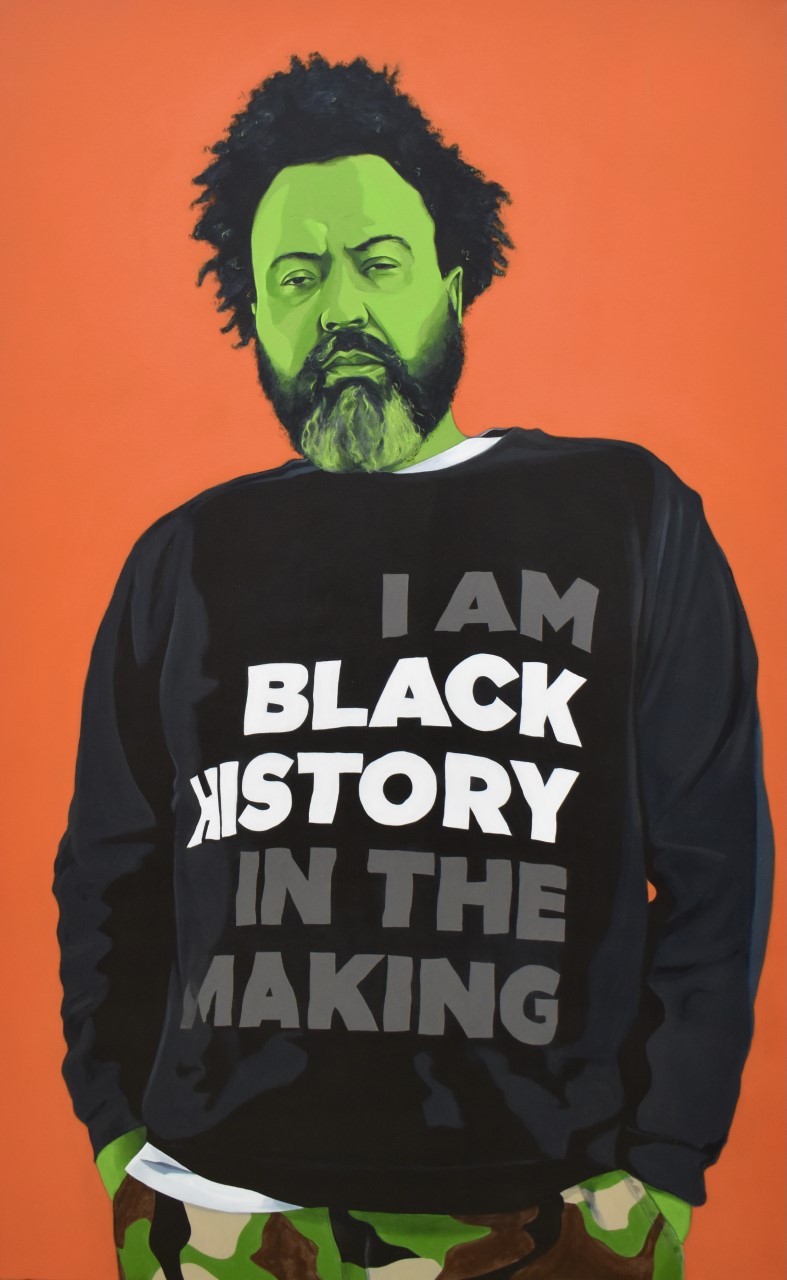

CH: So right now, I’m working on two different bodies of work. One body is, I’ve been ordering a lot of t-shirts. I guess everybody’s on Instagram. I get a lot of pop-ups and ads with Black t-shirt companies with positive messaging and stuff. I wear a lot of them and my wife wears a lot of them. I have a sister who has a t-shirt company, she makes a lot of them. So I started thinking about how, in a way, these t-shirts are a form of therapy for Black people. I don’t know how many people are gonna hear this podcast, so don’t steal my idea anybody.

TM: We’re copywriting it. It. We’re copywriting the t-shirt idea.

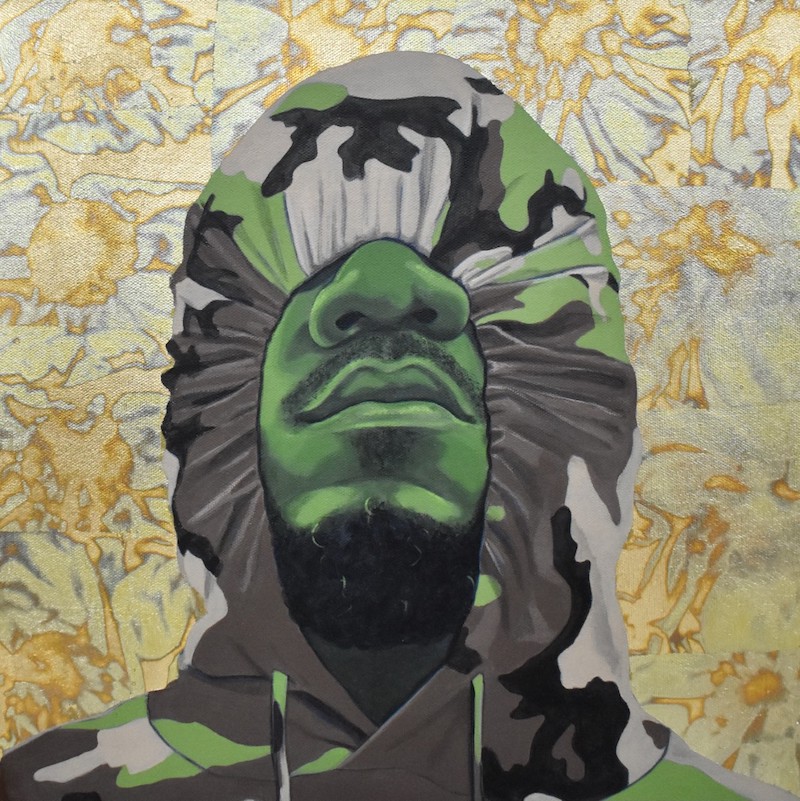

CH: So I started making work around that—around the fact that, you know, clothing is therapy, especially for this generation. I’m only a couple paintings in on that. But then I had another series that I started working on a couple months ago where I was examining the relationship with Black men and their hoodies, because I was listening to a podcast and one of the people on the podcast said Black men should not wear hoodies because they look threatening, and I was like, Man. So, to start, I just for some reason painted myself in a hoodie, right? I was just like, “Take that.” And then through my research, I came across Titus Kaphar’s Jerome project, and I saw the installation shot where he had a hundred paintings in the gallery. And then my goal was I want that shot, right? So once again, don’t steal my idea. But I had the idea of finding every Black man I knew with a hoodie. All my friends own hoodies, right? So I’m pulling everybody, “Hey, let me paint your portrait.” And, of course, everybody’s like, “What do I have to do?” I’m like, “However you want to look in this hoodie, just pose.” I’ve been getting images and I’ve just been painting them like crazy and then I’ve been doing some of my signature stuff with it. And my goal really is, I want that installation shot, man. I want to be able to put this work in a museum or a gallery and you walk in and you see a room full of Black men in hoodies. So that’s the goal for that work. And I think the messaging is clear, but, to be honest, my goal is really that installation shot.

TM: What would the lesson for the hoodie shot be? Because you talked about lessons you want to impart in your work. What would that one be? Don’t tell me what I can and can’t wear, obviously.

CH: Yeah, well, one, don’t tell me what I can’t wear. Two, you can’t judge a book by its cover, right? Some of the people sending me shots are doctors, others are artists, teachers. I have a friend who doesn’t have a job, so he’s just a regular dude with no job. But you can’t tell who’s who, right? It could be a senator. I’ve been researching this—I’ve found images of other people in hoodies where, you know, it could be the president, you don’t know. A hoodie is comfortable, right? We wear them because they’re comfortable. But I mean it was sparked by the fact that someone said Black men can’t wear hoodies because we’re a threat.

TM: I think that connects so beautifully to what you said about the Black body being politicized, right? As being threatening. Because it’s not the hoodie. Anything you put on a Black man’s body, because a Black man is inherently, in a white supremacist society, viewed as a threat. I hope that that’s a lesson that people learn today and yesterday and tomorrow. So I really appreciate that.

CH: Yeah, so how are you making sure you’re getting it right?

How do you talk about history in a moment where your students are traumatized? And then how do you talk about history as I’ve been taught to teach it, which is learning about the past to think about the present and the future.

TM: Oh gosh, that’s such a wonderful question. We’re grappling with so many nuances of that question right now, right? We have COVID, [and] there’s wide disagreement about being in person right now. And so there’s, you know, getting that level of it right. There’s also, how do you talk about history in a moment where your students are traumatized? And then how do you talk about history as I’ve been taught to teach it, which is learning about the past to think about the present and the future. And in terms of getting it right, I think it’s naming that really explicitly to my students—that we are grappling with these questions on a daily basis and also telling them about the problems of our archives. The fact—I think you mentioned this earlier—that ten years ago, being a Black artist was not what it is today, right? In terms of accessibility, in terms of your wellness as an artist, right? And your evaluation from a kind of external gaze and so those same gaps. So the fact that it wasn’t in vogue to be a Black artist ten years ago and it is now, that’s the case for academics. That’s the case for our archives. That’s the case for our newspapers. So when we’re teaching history and learning about it, most of what I try to do is, we’re missing a lot of this information. This is a version of the story.

It is your responsibility to dig for other versions of the story and then we teach them research skills, right? Let’s look at this and let’s bring in other voices and give our students a sense of responsibility of history as something that we create and something that we dig for.

To hear the full conversation between Clarence Heyward and Tatiana McInnis, listen to the Nasher Museum Podcast.

Clarence Heyward was born and raised in Brooklyn, NY. He is a painter and collagist whose work explores notions of the Black American experience. Heyward has shown his work nationally and has been featured in venues including the 21c Museum of Durham, the Harvey B. Gantt Center for Cultural Arts, the Block Gallery Raleigh, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, and (CAM) the Contemporary Art Museum of Raleigh. He was the recipient of The Brightwork Fellowship residency at Anchorlight in 2020, the Emerging Artist in Residence at Artspace in 2021, and was the 2022 Artist in Residence at NC State University.

Tatiana McInnis is an instructor of American Studies and Humanities at the North Carolina School of Math and Science. She earned her doctorate in English from Vanderbilt University in 2017. She has taught at Vanderbilt University, Texas Christian University, and Williams College, where she also served as the Associate Director at the Davis Intercultural Center. When she’s not with her students at NCSMC, you’ll find her snuggling her dog, Hurston (as in Zora Neale), “hiking” extremely moderate trails, reading, or tending to her mini garden.