This is a review of MONUMENTS at The Museum of Contemporary Art and The Brick at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles, California, on view through May 6, 2026.

MONUMENTS does something powerful and all too rare in recent group exhibitions of contemporary art. It does not tell us what to think and then congratulate us for having good enough politics to show up in support of that message. Instead, it risks complexity and ambiguity and holds a space open for analysis. It demands that we think for ourselves. In this way, MONUMENTS reminds us why art matters.

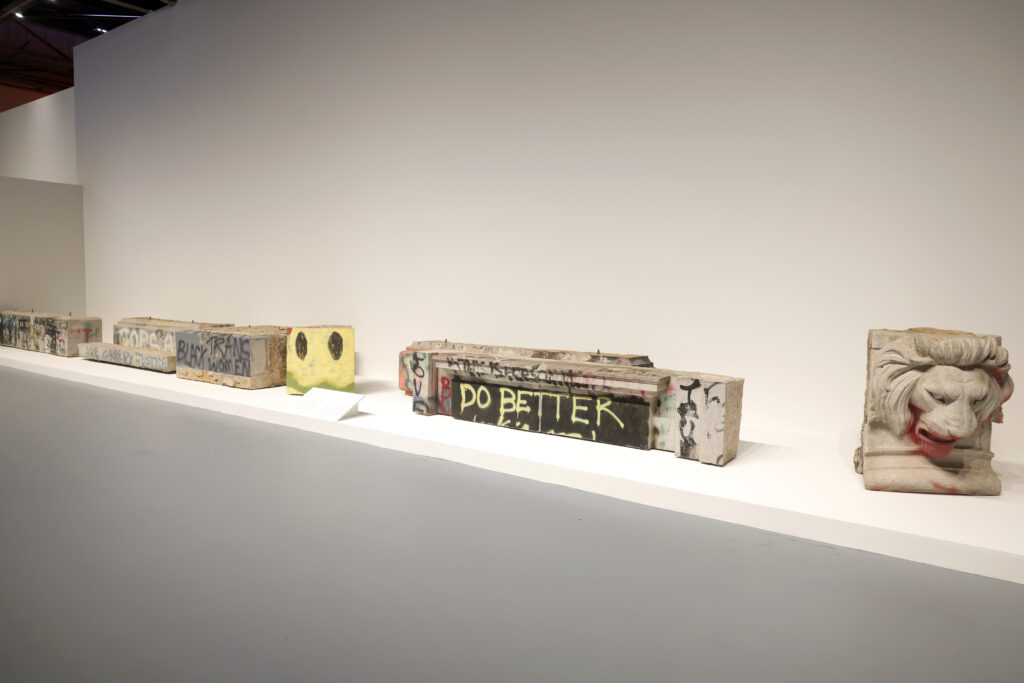

Spread across two Los Angeles venues, Geffen MOCA and the Brick, the show presents the work of nineteen artists—twenty if you count Davóne Tine, the musician who has collaborated with filmmaker Julie Dash. Many of these artists were commissioned to produce work specifically for this show. Together, they offer a variety of responses to Confederate monuments, alternately repurposing, countering, cutting up, and destroying them. But what makes this exhibition so challenging is that these artworks are on display along with multiple actual Confederate monuments in all their disturbing grandeur. The discordant juxtapositions and gnawing comparisons are the point.

Stupidly, I admit it now, I did not expect these decommissioned and often defaced memorials to be what they were and are, monumental. As a historian, I know how and why these sculptures were produced and how they did the work of justifying white supremacy. As a UVA professor and a longtime resident of Charlottesville, I know what it means to live with them. Every spring, I took my southern history classes on a Lost Cause walking tour of the town. When the City Council voted in early 2017 to take down Robert E. Lee from a downtown park beside the beloved library, I was thrilled. This brave decision was not a consequence of the Unite the Right rally. Instead, the plan to remove the statue prompted a half year of white supremacist gatherings that attracted thousands of armed right-wing radicals. On those fateful August days, they marched through my workplace and terrorized my students. They parked on my street and attacked my neighbors. They killed Heather Heyer five blocks from my house.

It is fair then to say that maybe, for me, this is all just too personal, since in different guises Charlottesville’s Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are present in this show. Leading art critic Jason Farago of the New York Times has argued that MOCA’s white-walled galleries “neutralize” the old monuments, making them “goofy and graceless.” I don’t think that is right. As surrealists long ago made clear, if something is on display in an art museum, we are being asked to think about it as art. Many Americans ignored these sculptures, positioned high on pedestals in parks where only the pigeons had this kind of close-up view, but it is impossible to avoid them here, on the floor in the white cubes of a contemporary art space, where they get the same kind of wall labels as the other works. When, after Charlottesville, Hamza Walker and Kara Walker, the original co-curators of MONUMENTS, came up with the idea for this exhibition, they knew exactly what they were doing. The inclusion of the actual monuments makes this show not just politically but also aesthetically risky. The threat here is real. Most obviously, this means the most extensive security I have ever encountered in a contemporary art space. It also means the contemporary artist has to contend not just symbolically but also materially with what it has meant to be monumental. It’s not surprising that some of this work does not quite meet this challenge. What is thrilling is that so much of it succeeds.

The central piece of this show, Kara Walker’s “Unmanned Drone,” stands alone in the center of the Brick, conjuring a visceral horror. It takes the form of a tall, upright figure, a Frankenstein monster sewn together out of a butchered equestrian stature, quite unlike any other previous imagining of the fusion of horse and man. In a sense, like the works in the group show at MOCA, it shares its space with a decommissioned monument. But unlike most of the other art present, it is made out of one—Charles Keck’s 1921 sculpture of Stonewall Jackson riding his mount Little Sorel.

Most of Kara Walker’s earlier artworks use the formal beauty of old artistic practices to seduce you into difficult and often menacing terrain. In Walker’s best-known works, the intricate graphics of eighteenth century cut paper silhouettes pull us into a minstrel horror show, an exhibition of what had been hidden, how the existence of slavery enabled white people to violently act out their sexual desires. What makes this work so powerful is that these violations both mean what they actually depict, and also work as metaphors for greed and economic exploitation. In an earlier sculpture, called “A Subtlety or the Marvellous Sugar Baby,” Walker borrows another set of practices—the smooth surfaces, curving lines, and pale weight of ancient, classical, and neoclassical sculptural techniques—and puts them to work transforming a naked mammy into a sphinx. Situated in a former sugar factory and made of that commodity that did so much to drive the slave trade, this piece too plays with the confounding doubling of material and metaphorical meanings, all the many horrible things justified by our “sweet” desire.

In “Unmanned Drone,” Walker has left behind this kind of redeployment of the beauty attached to earlier aesthetic practices. Instead, she keeps the fetishized form, the general on his horse, and reuses its monumentality for new purposes, to reveal the horror that has always been at its center. This new work suggests too that there are worse fates for a Confederate statue than being melted.

“Unmanned” is not hard to see. This general has been sliced to bits. But the idea of a drone is more complicated. In one definition, the word means a repeating set of notes, a wail, a buzzing, or a wash of some other unceasing sound, a metaphor for all relations in which something overruns a space. A drone can also be a zombie, a living figure without a mind and without intention, a worker bee put to labor for another’s purpose. These definitions, in turn, have given birth to another, a drone as a machine that streams images as it flies and is increasingly used to wage war without requiring any human to be present. A horse can be a hybrid of these last two meanings, a living thing put to war for another, a Little Sorel.

Walker’s sculpture establishes a kinship between the horse and enslaved people, living beings used for others’ purposes, that turns all the ugly tropes comparing Black people to animals on their ugly heads. As if making this point, one of little Sorel’s legs stamps right through the faceless head of Jackson, the “mind” of the matter. Little Sorel’s back legs remain intact. His nose and muzzle break out of what had been the Jackson sculpture’s interior supports. If any force is driving this collage of metal parts, it is Little Sorel. The remaining identifiable pieces of Jackson’s personhood, his legs dangling backwards over the horse’s buttocks, the cut-up arm on the pedestal, no longer cohere. The myth-man has become the drone.

Walker’s piece is and will continue to be a hard act to follow. As much as I liked seeing the Robert E. Lee statute that cost my own community so much pain and trouble melted down into metal ingots and waste, these displayed materials seem pretty tame here, after Walker’s masterpiece. It remains to be seen what the artist that wins the Charlottesville competition, sponsored by local organization Swords into Plowshares, will do with this stuff.

Cauleen Smith is the only other artist in the exhibition to make actual use of a monument. In her case, that work is an allegorical female sculpture by the artist Edward Valentine that once sat high up on an enormous classical column where she towered over a large sculpture of Jefferson Davis, also by Valentine, that formed the center of Richmond’s largest Confederate monument. Called the “Vindicetrix,” she embodied the unofficial motto of the Confederacy, Deo Vindice, Latin for “God, defender/ protector,” but also translated as “God will avenge” or “God will vindicate.” “Miss Confederacy,” as she was known colloquially, held her right arm straight over her head, with her pointer figure aimed at the sky, a gesture that was supposed to symbolize divine intervention.

Not taking any chances, Smith places “Miss Confederacy” in a gallery corner with her back to the audience, surrounds her with a reflective black material that enables us to see her from every angle, and focuses a surveillance camera in close on that upraised limb. In calling her own commissioned piece “The Warden,” Smith reminds us that it is our job to keep watch. Walking through the galleries of Geffen MOCA, you can do just that, viewing the live feed that plays on multiple screens, a closeup of that spirit-summoning hand pulsing faintly and glowing in a variegated blue light. The effect is stunning, even uncanny. Rather than animating a monumental horror like Walker, Smith has done something I did not think was possible. She has made us see the most dangerous quality of Confederate and, indeed, all forms of monumentality: its potential to be beautiful. In the past, Miss Confederacy watched over the Jim Crow South. Now, we watch over her. Where all this will end up in the future is anyone’s guess. “Keeping” Miss Confederacy is risky.

Another way of taking the problem of monumentality head on is to bury the grandiose romanticism of these decommissioned pieces in a grand counternarrative of Black flourishing. No piece exhibited here does this better than Julie Dash and Davóne Tines’s “Homecoming,” which imagines Black voices as their own kind of monumentality. Dash, a pioneering Black filmmaker, shoots Tines, a bass-baritone, and his band The Truth performing “Let It Shine,” their version of the Movement song “This Little Light of Mine,” in Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Charleston, weaving in footage of an ancient live oak called the Angel Oak Tree outside that same city as the soundtrack plays. Viewers paying attention will know this church immediately as the site of a mass shooting of nine ministers and congregants by a white supremacist gunman during a Bible study. But as images of the interior and exterior of the 1891 sanctuary and its members make clear, this church called “mother,” founded long before Emancipation, is, like Black life in America, about so much more than tragedy. Tines’s voice, with its incredible range and resonance, animates Dash’s footage and soars out of the film and into the space where you view other parts of the show.

Prints from photographer Nona Faustine’s White Shoes series, a body of work in which Faustine made images of herself nude or bare-chested in white heels in New York locations connected to the institution of slavery, have often been exhibited before. But their inclusion here makes them seem less like photographs and more like stills documenting a piece of performance art in which Faustine turns her own particular Black female body into a new kind of allegorical figure, a monument. Particularly powerful is an image called “From Her Body Sprang Their Greatest Wealth,” in which a naked Faustine stands on a makeshift auction block in the middle of Wall Street.

I want to end with the filmmaker Kevin Everson’s equally effective and yet altogether different counter monument, a spare and quiet black and white film about working-class Black men. In 1984, Richard Bradley put on a Union uniform, climbed a forty-foot pole, and cut down a Confederate flag hanging outside the San Franscisco Civic Center as part of a historical display. Bradley was an activist, a member of the labor movement, and a leftist. A sign unfurled as he shimmied up the pole proclaimed, “Finish the Civil War—Onward to the worker’s state.” Everson cuts historic photographs of Bradley’s feat into footage of him walking around Orangeburg, South Carolina, where he had retired, and the site of a little-remembered 1968 massacre in which police killed three Black students and injured twenty-eight. When asked how he managed to climb so high so fast, Bradley replied, “Practice, practice, practice,” a line that becomes the film’s title.

To fill in the details, Everson shifts to footage of a Black man who worked for decades as a telephone lineman. As he explains how he climbs poles and performs other tasks, his descriptions become a kind of vernacular poetry, a testament to his steadiness and craft, a grounded art that keeps him from being electrocuted. Bradley is one hero here, a precursor to all those who would follow in this work of removing Confederate symbols. But somehow, it is Everson’s lineman who lingers in my mind, a Black working man with his own kind of monumentality, a deep and yet matter-of-fact competency that looks like the opposite of our current national leadership.

MONUMENTS challenges us to think for ourselves about the always open question of what has and will count as monumental, not just what we choose to memorialize, and whose histories will be told but what aesthetic forms we will imagine to try to carry those stories into the future. The answers are not going to be easy or clear. No doubt, we will disagree.

There is simply no other way to be free.

This essay is part of our Shutter art and photography series.

Grace Elizabeth Hale is the Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia and a historian who writes about twentieth century America and the regional culture of the South. She is the author of In the Pines: A Lynching, A Lie, A Reckoning, Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture, A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America, and Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940. Her new project is “They Don’t Own Us: Harlan County, Kentucky and the Past and Future of Working Class America,” the dramatic story of the first strike in US history to successfully adopt the tactics of the 1960s social movements and what it reveals about the forgotten history of labor’s fight for economic equality in the 1970s. Her essays and op eds have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, Slate, and CNN, and she writes regularly about photography and other forms of visual art for museum catalogs and photo books and in her series Shutter, published by Southern Cultures.

Header image: Walter Price, Pond de Rivaaahh, 2023. Acrylic and gesso on canvas, 65 x 130 in. (165.1 x 330.2 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo by Elisabeth Bernstein.