In early 2022, we visited each other’s studios in Baltimore and Chestertown, Maryland, to discuss the influences of historical memory, ancestry, and artists’ roles navigating time and place within white supremacy. Our first collaboration, in 2020, was the exhibition Rights and Wrongs: Citizenship, Belonging, and the Vote, hosted by the Peale Museum at the Carroll Mansion in Baltimore. A few months later, we were on a panel together, “Imagining the Future: Public Art Confronts the Past,” hosted by the unc Center for the Study of the American South. What follows is a snapshot typical of our dialogues, meandering from past to present, art to life, and personal to public.

Lauren Frances Adams: I want to start with a question about artists taking on the history of whiteness or white supremacy. What do you think artists’ roles are?

Jason Patterson: I don’t think there are enough white artists making work about the existence and effects of white supremacy, and I’m a little sad about that. I know tons of white artists that have a good understanding of how whiteness works that they mostly learned about in college. And I think if they used their practice to work their way through that, good things could come from it.

LFA: I think it’s a really important way to think about intentionality, which is that unless the stated intent is anti-racist or centering concepts of white supremacy and whiteness, then it’s a stretch. It’s part of the conversations we’ve had about people who don’t want to consider themselves implicated in the long line of history, a rejection of applying the standards of the past onto the present, or the present onto the past, and how that’s a kind of escape hatch for a lot of folks who want to think of themselves as exceptional to history. Or that history is somehow exceptional to the present.

This reminds me of a quote in the writer Clint Smith’s new book (How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery across America) from a member of the Sons of the Confederacy about the removal of the Confederate flag at the South Carolina state house. The man says, “You’re asking me to agree that my great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents were monsters.” And it’s like, he gets it, but doesn’t get it. Your ancestors believed that African Americans were subhuman and that it was moral to treat them like livestock, and they were willing to go to war to make sure that was societally and culturally sustained. That is monstrous. Nothing can absolve their legacies from that—from believing in the violent subjugation of Black people and fighting for that.1

LFA: So much is placed on the ideas of rightful lineage and the goodness of our forebears, specifically in one’s own family line—honoring your elders, both the living and the dead. And then there’s the cultural and nationalized concept of it, which is how we end up with these Confederate monuments and colleges named after dishonorable people.

My ancestors, as far as I’ve learned—and I’m getting better at the genealogy—many of them were enslavers. So when I grapple with this idea of respecting your ancestors and elders, that comes in direct conflict with regard for their bad morals or wickedness. Outside of strict genealogy and family lineage, there’s cultural ancestry or social relationships. There’s also place and the meaning of home, material culture, even epigenetics—what is passed down to you, identifying with people of the past, and what it means to be human, including what it means to relate to one another across time, including one’s ancestors. The tree that blooms outside your window in spring is the same tree, or elicits the same feeling from the tree, that my ancestor may have experienced two hundred years ago. For me as a white person, ancestry and generational connections are always complicated by the necessary disconnections and resistance to the evil that was and is perpetuated.

JP: Also, for every time a white southerner hears that these Confederates were evil and bad people, they can run to volumes of books published throughout the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, telling them the opposite, and they sound legitimate. And at the time they were published, they were absolutely legitimate texts.

I remember when I was reading Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s The Condemnation of Blackness, which covers the demonizing of Black people in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in academia, science, government, and policing. This was the first wave of sociologists, in the 1890s. But a lot of them are white southerners, educated in the Ivy League, writing for major publications like the Atlantic. Well-educated people at the top of their field, arguing in a very convincing “scientific” way, why Black people are inferior. To them, the problem with race, in the 1890s and 1900s, was their fathers and grandfathers’ faults because they weren’t the slave owners. In their minds, their fathers left them to deal with this free Black population. And this framing helped them justify their race science, and the subjugation and apartheid they were insisting was best for American society. I mean, in 1905 and 1906, President Teddy Roosevelt gave speeches at the Black colleges Hampton and Tuskegee and told these Black students that inherent criminality is in their nature and that they are more of a danger to themselves than anything white people may do to them. And during his presidency, at the beginning of the 20th century, Roosevelt’s views on race were seen as liberal and progressive.2

Now, I think, confirmation bias might even be easier today with the Internet, and with how it currently is politically advantageous to discredit the history of racism and how it still exists. In 2022, if you want to believe that the Confederacy was reasonable and you want to believe that racism isn’t as bad and isn’t as impactful as Black people are saying it is, there are more than enough, seemingly legitimate, sources telling you what you want to hear. I mean, Fox News is the most watched news network. And how they talk about race is not nearly as different as it should be from how race was talked about one hundred–plus years ago.

President Biden nominated Ketanji Brown Jackson, a Black woman, for the Supreme Court. Tucker Carlson, whose program is the most watched show on the most watched news network in the United States, is questioning whether or not she was even able to get into law school. Not unlike how someone in an equivalent public position, in the 1890s, would have.

LFA: Given these conditions, what do you think is the societal role of artists?

JP: Well, for me, as a history-based artist, I see this history, and I want to use it to make artwork to present to people. And that’s the responsibility that I’ve taken on. These things happened. They were recorded. I know I can interpret them in a way that I believe will resonate with people. And so that’s what I try to do with the work.

LFA: It’s often happenstance that we even have artifacts or ephemera or evidence. And then it comes down to bringing a capable, interpretive eye. Without that, it’s just reinserting some of these artifacts back into a narrative of white supremacy.

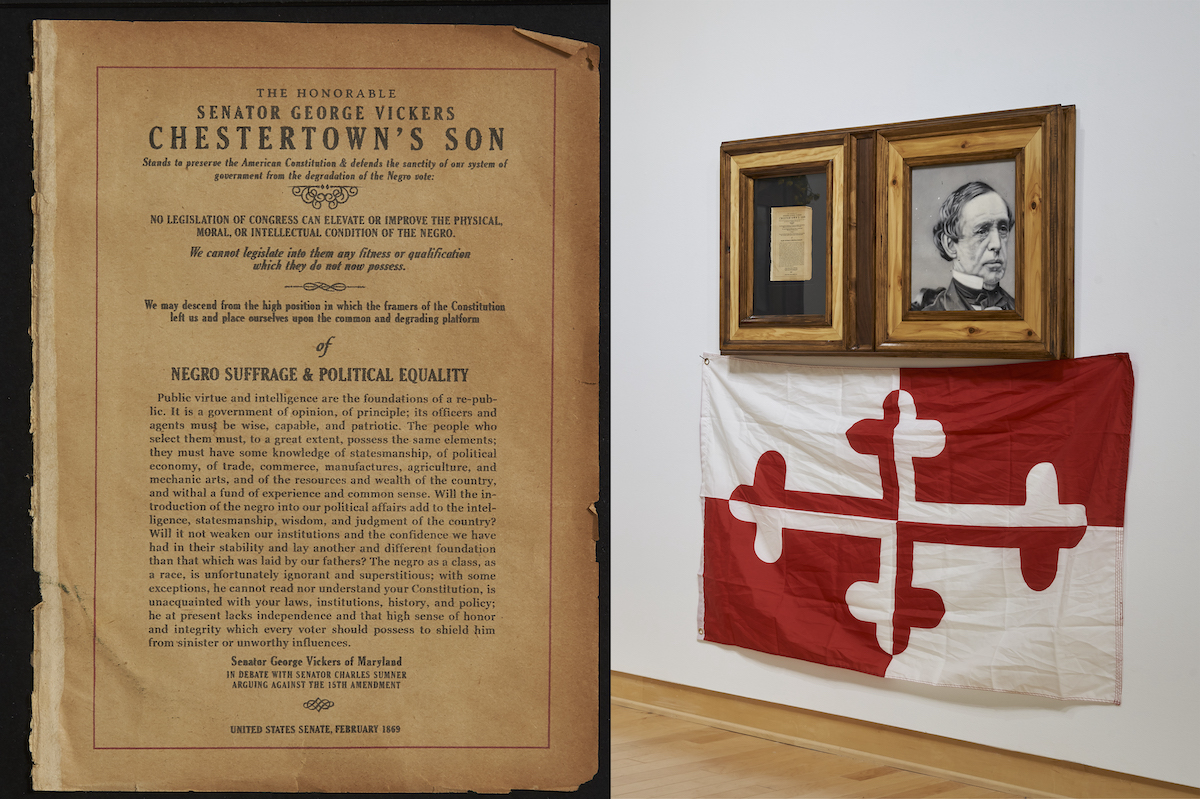

JP: And I think that’s where I see myself as being somebody that can counter those assumed narratives. An example that comes to my mind is that classic narrative that the Civil War wasn’t about slavery. The Articles of Secession from southern states literally cite slavery as a reason, if not the main reason, for secession. People today will say the South seceded over things like the federal government was overreaching its power. But overreaching its power how, exactly? These vague not-slavery reasons almost always come back to actually being about slavery. And so, to challenge that, I just take that actual text from the nineteenth century, put it on a wall in an aesthetically pleasing way, and that’s it.

LFA: There’s so much mental gymnastics and willful ignorance around this history, instead of actually reading what the people of that time very clearly said and what they were actually doing when it came to race. And so that’s what I try to do with this work. Discrediting that Lost Cause propaganda and just, in clear context, quote what these men said they believed in. That is about the lack of education and historical amnesia that happens in this country. Because we have pretty terrible educational standards about history.

JP: Absolutely.

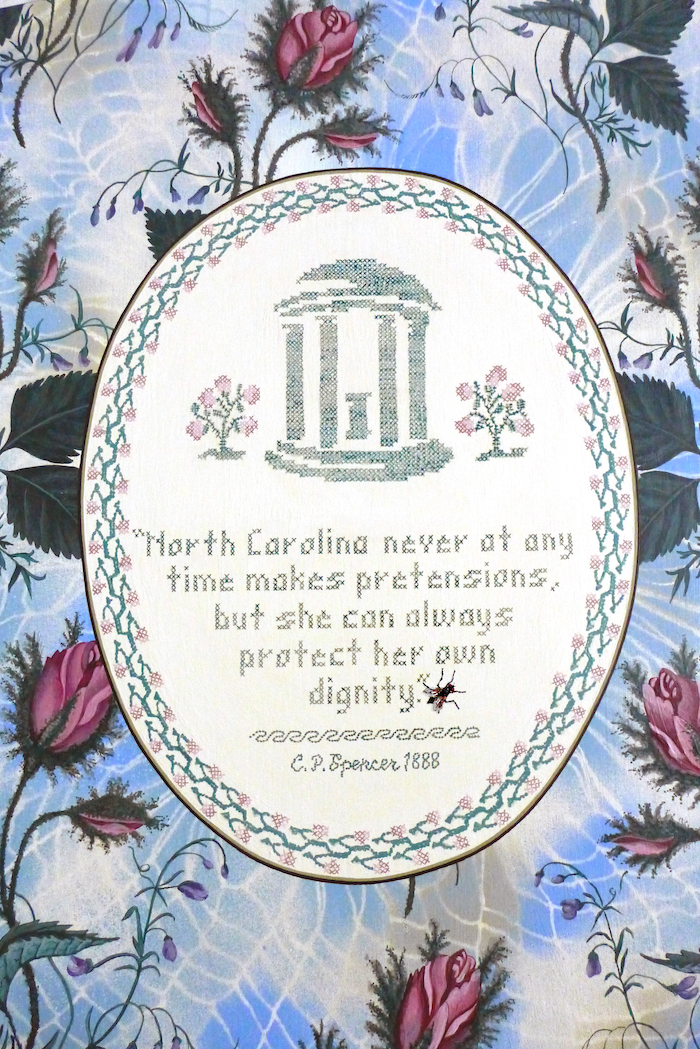

LFA: I was educated in public schools. What was not presented, or was glossed over, reinforces remembrance. A book may include facts, but how it’s reinforced makes information culturally important. Cornelia Phillips Spencer was part of that. Her textbook used in North Carolina schools was Lost Cause propaganda that still permeates educational standards about the nineteenth century, Civil War, and Reconstruction history. I used the phrase “deep fake” last time we were talking.

JP: If you’re talking about it in my work, I think it’s a figurative use of the phrase. It’s a reference to something that’s really relevant now. With a real deep fake, you’re trying to trick people. I am very deliberately not trying to trick people because the wall text and labeling clearly state that these are recreations. But both of those—a real deep fake and what I’m doing—do have similarities where you’re trying to put people in a certain mindset. Mine isn’t unethical and manipulative, or at least if it is manipulative, it’s a manipulation that’s acknowledged, like saying, “I want to put you in this head space,” as opposed to just trying to fool people.

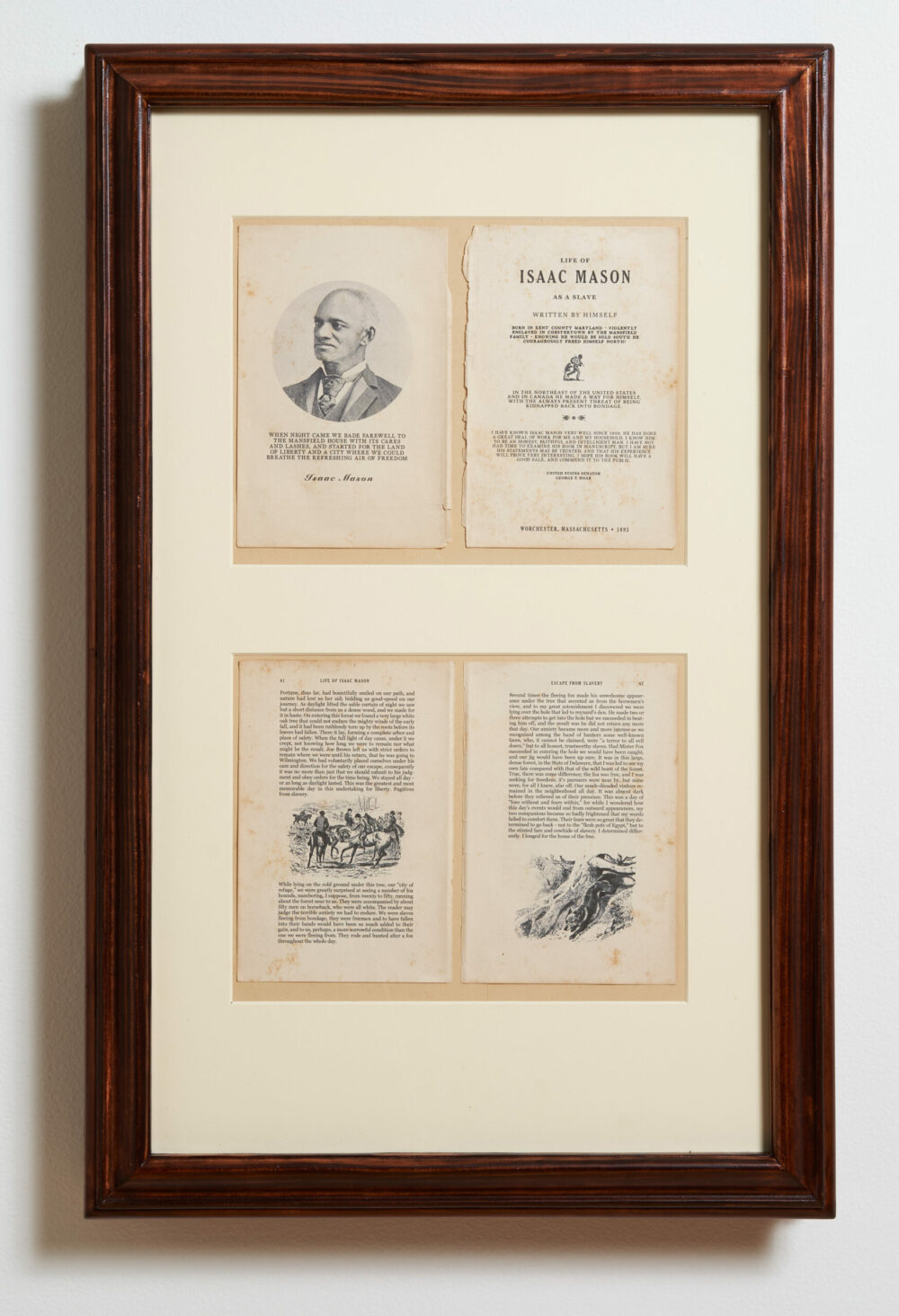

LFA: I think that’s a connection with our work. We both investigate images from historical contexts in the present and present those as credible, persuasive communication about the past. Your beautiful portraiture means I can commune with these people in the specific way you convey their physical appearance. That reminds me of your work about Maria Stewart, which you included in the show I organized last year, Rights and Wrongs. That work helps bring to the fore phenomena that otherwise gets trapped or stuck in book pages. In my work, too, I think about anachronistic objects. There are objects from another time displayed in the present, reinterpreted as platforms or sites to twist the logic from the way it would’ve been used in the past. Which is in service of a way of thinking about the past that we absolutely have the tools for now, especially when we’re talking about this inheritance of white supremacy—thinking through how much white people leave on the table. Your work concretizes historical conditions. You do that with respect and kind regard, too. Your frames are getting more and more elaborate. Your attention to detail is another way of demonstrating care.3

JP: Yeah, absolutely.

LFA: There are at least two different kinds of visors or lenses you put on in your work. One kind celebrates and focuses on clarifying, giving more sensitive information about the history of Black folks in the Eastern Shore, or more broadly, in American history. And then you have it right beside another piece that shows text written from the perspective of a white colonizer who profoundly influenced, in both language and visual culture, the ways that African peoples were received in Northern Europe. So that second kind of work touches on derogatory, degrading visual and textual information.

In my work, I have to determine whether it is a celebratory or incriminating project. The project at the Center for the Study of the American South is an incriminating one. It focuses on Cornelia Phillips Spencer’s influence on unc-Chapel Hill, which was intertwined with her political activism and editorial voice that advanced Lost Cause Confederate mythology during and after the Civil War. Her impact has had a strong presence on campus in the twentieth century, with a campus dorm named after her, and the influence she had on historical memory about the nineteenth century, specifically pertaining to North Carolina and the South.

There are other projects where I’m trying to open that up some, looking for good ancestors, or visualizing the incredibly rich history of political and social resistance to oppression and white supremacy. In the case of the project at the Baltimore Museum of Art, I was working with objects that have been inadequately and incompletely contextualized in relation to their makers and shaping an interpretation that opens up possibilities for historical memory.

In Forget-me-not, I transform the historic textile tradition of Baltimore Album Quilts. These quilts are typically interpreted as objects of nineteenth century white Christian middle-class Baltimore women that narrowly celebrate their religious, social, and economic networks. I am interested to expand an understanding of early Baltimore and how material culture, including the quilts and genres such as portrait painting, have plenty to tell us about power and identity in America. Further meaning can be forged in narratives of peoples, both named and unnamed, who shaped this city. In the cases of the quilts, that also means the enslaved and indentured who likely helped produce them, but who weren’t credited. In the context of the museum and what it habitually collects and for whom, this opens possibilities for meaningful connection and disruption of other objects from the same time and place.

An example would be the cabinetry of John Needles, a white Quaker whose woodwork has been preserved in many collections, but whose efforts as an abolitionist in Maryland have been marginalized within historical memory. In the part of the wallpaper painting where I reference Needles, I have selected text from his brief autobiography of how an abolitionist press that he had helped finance, The Genius of Universal Emancipation, ended up as interiors and shipping materials for Needles’ cabinetry. I enlarged a section of his wood carving and swapped it with the Washington Monument of Baltimore that originally appeared on an album quilt. This artistic gesture problematizes monuments, and underscores what often happens in museums whereby a focus is on the beautiful craft, despite the biographical relevance of the makers and the underutilized potential for social and political connections. Similarly, this happens at plantation sites, when the big house and its domestic decorative rigamarole supplant any real truth-telling about the violence of slavery and the extreme efforts required to maintain white rule. My roles and responsibilities are about how to navigate that content, especially if I’m trying to create a project that’s incriminating of whiteness, and not reifying derogatory imagery.

I want to understand how you decide which kind of work to make. You’ve got an image you’re working on that shows a man who’s a diner owner. It’s a freeze-frame still from this historic film from 1962, which shows segregation protests in Chestertown, Maryland. The white diner owner is depicted with some of his supporters and in front of him, and between us and this white man, is a protestor who is a Black man.4

JP: He’s the only Black figure in it.

LFA: How do you figure out how to frame that?

JP: So in sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s book Racism Without Racists, he opens with a quote from the French-Tunisian writer Albert Memmi: “There is a strange kind of tragic enigma associated with the problem of racism. No one, or almost no one, wishes to see themselves as racist; still racism persists, real and tenacious.”5

I think that quote really explains how racism has worked in the United States since the 1960s. Not only do white Americans generally not implicate themselves as contributing to racism and white supremacy today, but it goes further when we remember American culture and societies historically. We don’t acknowledge, or don’t acknowledge nearly enough, the inherent racism and white supremacy that has been a fundamental part of this country. So often, white Americans, many of whom believe that racism is no longer an issue, struggle to explain how that came about exactly. If they have an explanation, they often cite the Civil Rights Movement—as if the millions upon millions of white Americans who saw the prior century of Jim Crow apartheid as normal, appropriate, and ideal all stopped being racist and accepted racial equality after the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s. They magically stopped believing in it, teaching it, or expecting it within American society?

So for the in-progress diner piece, I wanted to show the restaurant owner standing up for his perceived right to racially segregate. At the same time, I’m showing this rather beautiful backside profile of the Black man who the restaurant owner is seemingly reading a statement to—a statement justifying his right to keep his restaurant whites-only.

This still was not easy to capture because in the footage the Black young man blurs in and out of focus. But I did eventually find the right still! I was particularly interested in capturing him because the first thing that came to my mind when I saw him was Kerry James Marshall’s series Stono Group, including four portraits of Kato, an enslaved Kongolese man, who was reported to be the leader of the Stono Rebellion in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1739.6

With my Rosa Parks piece, I think that there are just a handful of images that people keep reusing that are only a tiny bit of the massive number of images of her. Much like MLK. I swear there are like ten images of him that are used over and over. Same goes for Parks. I wanted a candid image of her that isn’t one of those well-known images.

This image is over a decade after the bus boycott, and this piece is an image of her in 1968. It’s a cropped detail of a photograph of her with Shirley Chisholm, when she was supporting Chisholm’s run for Congress. The common narrative of Rosa Parks really undermines how much of an accomplished civil rights worker she was, specifically before the bus boycott, but also after. And we also are virtually unaware of how the backlash of the boycott really turned her life upside down.

Rosa Parks wasn’t some feeble old lady when she refused to give up her bus seat. She was in her 40s, and not giving up seats to white people was a plan the local naacp had already established, and she wasn’t the first woman in Montgomery to do it. She was also a seasoned and high-ranking Alabama NAACP member before the boycott. And maybe most importantly, it’s omitted in her common narrative that she lived most of her life in Detroit because she had to flee the South after the boycott because it wasn’t safe, and she and her husband couldn’t find work because of her notoriety.

The card on the canvas under the portrait explains the image’s setting. And my hope is that the viewer is taken aback a little bit, realizing we’ve never really heard about the post–bus boycott Rosa Parks. Hopefully, they’ll try to learn more.

LFA: I’m interested in your thoughts about place since you’ve relocated to the Eastern Shore. Driving here [to Chestertown, Maryland] from Baltimore, there’s a certain quality of the land, and the relationship to the Chesapeake Bay.

JP: Location for me is very exciting because I didn’t really think about it when I lived in Illinois and it’s impossible not to here. Illinois is young compared to Maryland. I grew up in Champaign and Urbana, Illinois. Urbana was established in the 1830s, but these twin cities didn’t really get going until the late 1860s. So now living in a town and county that were well-established in the seventeenth century is very new to me. And you can see and feel those four centuries in the architecture, in the culture, and even in the landscape. And all that history and how it relates to race is very palpable.

Yes, people may know that Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman are from this region. But most people, even some people that live on this peninsula, may not know that Henry Highland Garnet is from this county. I’m sure many people have seen the famous photo of Gloria Richardson marching while she pushes a national guard soldier’s rifle out of her way. But I don’t think people know that photo was taken in Cambridge, Maryland. There’s so much very relevant, but not exactly well-known, Black history here, and I am grateful I can unearth it and make artwork about it.7

LFA: When did you realize that specific connection with the Choptank River and Harriet Tubman?

JP: Well, when I knew I was coming here, I was like, oh, I think this is where Douglass and Tubman are from. And then we were driving here the first time—we were driving into Chestertown on 291 and there was a sign that said the highway is dedicated to Henry Highland Garnet. I knew who he was. I had already been planning on making work about him. But I did not know he was born in Kent County. The first thing I thought was, “Do the white people here know who Henry Highland Garnet is?” I mean, this man was a radical for his time, the Malcolm X of the nineteenth century. He encouraged enslaved people to kill their masters. And unlike Douglass and Tubman, there aren’t any sanitized narratives about him. And after being here for almost four years, the answer is “no.” Most people here do not really know who Henry Highland Garnet was.8

And getting back to the landscape of this region. The first year we were here, we actually lived in Wilmington, Delaware, and commuted fifty minutes. Sometimes I would take the country roads while I listened to a Harriet Tubman audiobook. And when I listened to the biography and drove through this landscape that she could have passed through, that was profound for me. It’s given me ideas on how to incorporate landscape into the work.

LFA: That’s hard not to look at the land and think about.

JP: Absolutely. I’ve done work on Isaac Mason, who published a slave narrative in the 1890s. He was born in Kent County and enslaved in Chestertown. The Kent Cultural Alliance is Kent County’s arts council, and the mansion Mason was enslaved in is now the kca’s headquarters. I’m on the kca board and the building my studio is in is right next door. In Mason’s narrative, he tells his story of escaping from this mansion and getting to Wilmington and eventually Philadelphia before he eventually settles in Massachusetts. Being so physically close to history like that is really new for me and quite inspiring. So, yes, I am really thinking about location and I really hope I can start incorporating work about, and of, this actual landscape into my practice.

LFA: So much of your work is about picturing the figure as a way of framing historical memory—likewise, the concept of land can be a kind of portrait, which can convey information about history. Y’all have a lot of plants around your house—that’s part of being in touch with, knowing, and understanding different kinds of life that have needs. Some urgent and some more relational, right?

While driving here I wondered, are these landscapes the same now as they were then? Not the same vista Tubman would’ve seen, yet thinking about proximity, that there is somehow a relationship over time and wondering what connections are possible to trace. More than just picturing a vista, it’s about experience and the facts of the soil and the many kinds of witnessing. I talked about the tree outside your window earlier, all those things seem really ripe or potent with meaning. You can flip a signal and tune into it.

JP: Yes, when I did my project at Washington College (which was a series of work on the Black history of Washington College and surrounding Kent County), one of the artifact artworks for the college’s archive that we used was this painting from the 1790s commissioned by Simon Wilmer. Wilmer was a wealthy landowner, enslaver, and benefactor to the college when it was founded in the 1780s. The painting depicts his land, his home, and Chestertown in the 1790s with the college in the background and Wilmer himself on horseback, but also the people he enslaved. In the image you can see landmarks that still exist. Although his house looks much different now from additions and renovations, the original eighteenth-century parts are still there. And I’m sure if I followed the landmarks of Chestertown in the painting that still exist today, I could find my street and where my house is now. There are still physical things here, and parts of the landscape, that connect us to that past.9

LFA: Like one of those kinds of fictional landscapes that’s an imaginary composite, intended to evoke domination.

JP: I don’t know what I would exactly make about the landscape just yet, but I still want to think about it and see what could come from that. I just started reading the historian Walter Johnson’s most recent book The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States. Most of his work is on slavery and, to me, one of the most compelling things he’s written about is how the landscape architecture of plantations were designed for surveillance.10

LFA: That sounds related to the concept of Plantationocene. That the plantations of yesteryear, as historic sites of enslavement, were physically designed to funnel back all physical, visual, and economic power from the lands and people around it to the big house. And that jails andprisons, or corporate headquarters, a factory or warehouse, enact similar relationships of power now. Sited in the past, yet still functionally how land and labor is ascribed, extracted, and controlled today.

JP: When the Frederick Douglass historian David Blight was here during his book tour, he spoke at Washington College. The next morning, I got to have a breakfast conversation with him and some students and faculty. One of the students, who is from rural Maryland, had observed that in his small town the current richest family in the community was a slave-owning family in the nineteenth century.They still live on the land where their family’s plantation was located and have extended their wealth with something like a car dealership. He also observed that the African Americans in the community, who are descendants from the people that family enslaved, still live in poverty and some actually live where slave quarters used to stand.

This was really good because this student was making this observation and contemplating what it means about our history, society, and his personal family history. I think sometimes it’s actually a problem when we try to deal with these histories and how they are still impactful today—we try to make knee-jerk reactions and feel like we have to solve the problem in the moment. He was really trying to sit with us and think about it critically and try to understand it better and more completely. I think that’s really important when we are trying to reconcile with the past and how it affects the present. We really need to have a full understanding of these things before lasting change can really happen. But I think that is something that is really hard to do.

LFA: Well, I teach in an art school, so this comes up a lot when agitating for needed change. On one hand, there’s work that needs to be sat in and get mucky and take your time through, because it’s about undoing more than just the name of a school or a dorm (in the case of Cornelia Phillips Spencer at unc). Because that’s a representational piece that matters, but it’s not the only bit. If we stop there, or if we just put someone’s name on a highway marker and there’s no real commitment made in other ways, it’s incomplete. Suspicions arise when the suggestion for solutions is another committee to explore the issue and make nonbinding recommendations. And it’s that kind of slowness of time. I think that struggle between our needs to sit with this and feel all that, and there’s also confronting potential despair—nothing’s happening. Nothing’s going to change.

JP: That’s a really good point. Trying to balance necessary contemplation and education with timely and meaningful action and change. It’s extremely complicated. And I think that’s one of the biggest struggles when we’re talking about reconciliation and reform and making it happen the right and sustainable way.

This essay was first published in the Inheritance Issue (vol. 28, no. 3).

Lauren Frances Adams is a painter who lives and works in Baltimore. She grew up in Snow Hill, North Carolina, on a pig farm. Her work engages political and social histories through domestic ornament and has been exhibited across the United States at museums, galleries, and artist-run spaces.

Jason Patterson is a Black history-based artist. Although his work focuses on all African American history, Patterson’s recent work speaks on the Black history of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Patterson’s work consists of portraiture, woodworking, and the recreation of historical documents. He is currently a fellow with Chesapeake Heartland: An African American Humanities Project.

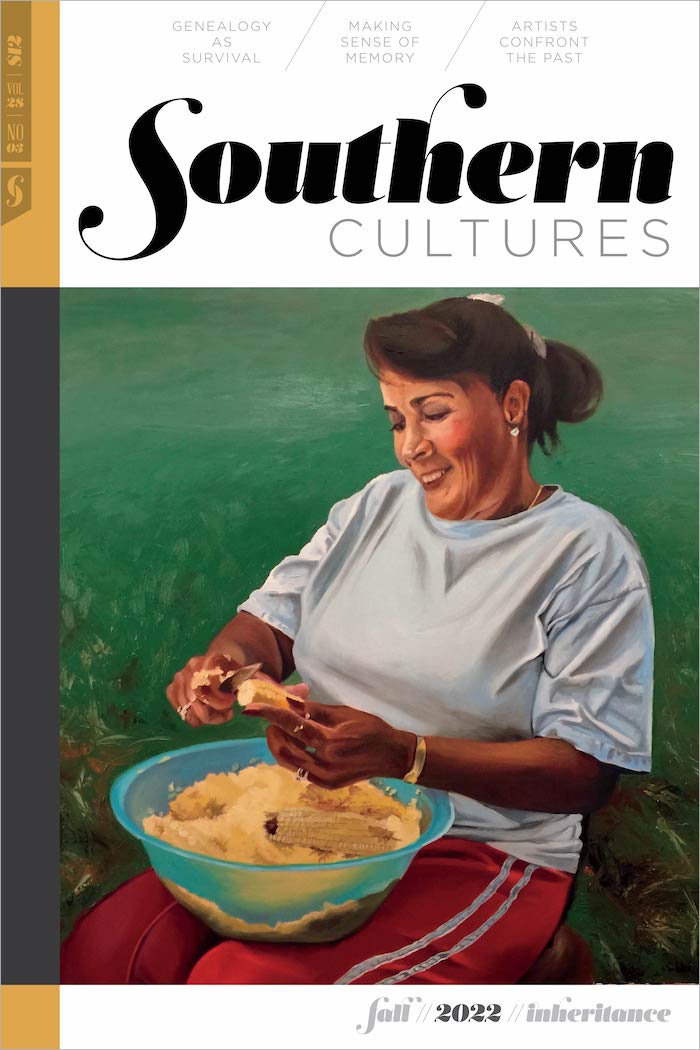

Header image: Lauren Frances Adams, Forget-me-not, 2021. Vinyl wallpaper with hand-painted collage. Detail of installation view at All Due Respect, Baltimore Museum of Art, 2021. Photograph by Lauren Frances Adams.

NOTES

- Campbell Robertson, “Flag Supporters React with a Mix of Compromise, Caution and Outright Defiance,” New York Times, June 23, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/24/us/politics/supporters-of-confederate-battle-flag-watch-as-symbol-is-stripped-from-public-eye.html.

- Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 170–171; “Roosevelt at Hampton,” New York Times, May 31, 1906. The Tuskegee speech can be found in Theodore Roosevelt, The Works of Theodore Roosevelt, vol. 18 (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1923–1926), 465. Roosevelt was also on the record as stating that rape was the single cause of lynching. Theodore Roosevelt, The Works of Theodore Roosevelt, vol. 17 (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1923–1926), 411–412. For more on Roosevelt’s attitudes toward African Americans, see Thomas Dyer, Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1980), 89–92, 99, 109.

- Marilyn Richardson and Maria W. Stewart, America’s First Black Woman Political Writer: Essays and Speeches (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987).

- Carle Conway and Leslie Prince Raimond, home movie footage of the Chestertown Freedom Rider protests, February 1962, digitized 8mm film, Chesapeake Heartland Digital Archive, https://archive.chesapeakeheartland.org/index.php/Detail/objects/1422.

- Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists, 4th ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), 1.

- Kerry James Marshall, Stono Group, “Kato,” 2012, Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/668402.

- Gary Gately, “Gloria Richardson, Fiery Civil Rights Activist in Maryland Showdown, Dies at 99,” Washington Post, July 16, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/gloria-richardson-dead/2021/07/16/efff2b7e-2253-11e5-84d5-eb37ee8eaa61_story.html.

- Peter Heck, “Garnet to Be Honored with Renamed Road,” Kent County News, June 29, 2016, https://www.myeasternshoremd.com/kent_county_news/news/garnet-to-be-honored-with-renamed-road/article_1f24db89-a559-5be2-9786-4897263bc318.html.

- Jason Patterson, “On the Black History of Kent County & Washington College,” Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience, Washington College, Chestertown, Maryland, 2021, https://chesapeakeheartland.org/exhibit-main.

- Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 209–243.