Vidalia Mills had only been up and running for about a year when Eric Goldstein went on his quest. As soon as he’d confirmed that the demolition company was in possession of what he was looking for—that the machines hadn’t been destroyed after all—he flew from New York City to Greensboro, North Carolina, that same night in 2019. He met the demo guy at the shuttered factory and asked to see the goods. They were untouched, just as the last workers had left them. “I could not believe what I was looking at,” Goldstein said. They struck a deal on the spot, and within ten days the precious cargo was on its way to Vidalia, Louisiana.

The entire transaction was kept top secret, NDAs and everything, not that anyone was paying much attention to Vidalia Mills. “They thought we were crazy,” said Bob Antoshak, communications advisor and part owner of the company. Who would open a new textile mill in the United States in this day and age, when most production had long since left the country and the remaining mills were hanging on by a proverbial thread?

But the Vidalia Mills founders, all longtime industry veterans, knew that they’d found a holy grail of sorts, and they planned their reveal carefully. They waited until a group of clothing brand executives and buyers, local cotton farmers, and trade press reporters had gathered in Vidalia for a tour of the organic cotton farms that would supply the mill with local, sustainable raw materials—like a farm-to-table restaurant, but with blue jeans. (“We want to be a ‘craft-brew’ of the denim world,” Goldstein has said.)1

BASF, the company that sells the organic cotton seed, had brought the international group to town, put them up in hotels in nearby Natchez, treated them to customary corporate wining and dining—and given them field tours of the cotton farms. “It was like 100, 110 degrees in the shade,” Bob said. “It was really brutal.” Several of the Europeans, who had never experienced that type of humid, subtropical heat before, began to faint. They were taken to sit in trucks with the air conditioning running to recover.

On the second day, the group visited the mill, entering a showroom with a glass wall that looked down onto the factory floor. But the view of the factory floor was obscured; a fire truck from the local station was parked right in the middle. The attendees murmured in confusion— had there been an incident? But Dan Feibus, the Vidalia Mills CEO, ignored the truck and moved ahead with the pitch: partnering with BASF for sustainable cotton production, grown in the USA, made in the USA, reduced carbon footprint, et cetera, et cetera. Finally, he waved to someone. The fire truck pulled away. It was time for the big reveal: six Draper X3 looms rescued from White Oak Mill, switched on and weaving wide blue ribbons of selvage denim.

“I’ve seen everything in life, you know,” Bob said, shaking his head at the memory of the mania that ensued. “The faces planted against the glass. And you hear yelling, crying, screaming, ‘We got to get out there!’ So we let them out and they went absolutely ape.” TextileWorld.com reported on the looms in their breaking news section the next day.

“It just blew wide. It helped put the mill on the map.” Bob smiled. “People don’t think we’re so crazy after that.”

My uncle remembers the way the denim flowed out of those Draper looms, waves of fabric stacking and pooling. He worked at White Oak on summer breaks in high school in the 1960s, before he joined the Air Force and headed to Vietnam. As a teenage temp, he had one of the lowest ranking jobs—basically, to run around and do simple tasks as ordered. One such task was making sure the stacks of fresh denim didn’t tip over; another was to gather carts of spent wooden bobbins. Sometimes he might fill in on a machine for someone who was out sick.

When White Oak shut its doors in 2017, blue jeans enthusiasts—denimheads, Bob calls them— went into mourning. “Who Killed the Cone Mills White Oak Plant?,” men’s fashion website Heddles (named for a type of loom) wanted to know. Much of the outcry centered around the fact that the mill had been the very last one in the United States producing selvage denim. Selvage denim is woven on a loom—like a Draper X3—that sends the bobbin, loaded with thread, back and forth across the vertical warp threads. Sending a single thread back and forth like this, rather than cutting it at the end of each row, creates a finished edge that doesn’t unravel. More modern industrial looms shoot hundreds of short threads across the warp at once, meaning that they can weave much faster, but leave raw edges along the sides of the finished fabric.2

It’s not just these technical details that make selvage denim special to connoisseurs. It’s the way the weave feels, the way that there are slight irregularities. It has character. Not quite handmade, but in possession of a human presence, the encoded knowledge of traditional techniques. That’s why they call it heirloom denim.

My uncle worked at the mill in the summer because my grandmother, who worked in the billing department, helped him get the job. That’s how things worked at Cone, the company that built and operated White Oak and other textile mills in the region. It was founded by the Cone brothers, Moses and Ceasar (correct spelling), and run by Cone offspring after them. Even after management implemented anti-nepotism policies in the 1950s, it was common for family members to work together at the mill, often for successive generations. My grandmother grew up in White Oak Village, one of the company towns Cone operated beside its factories, because her father worked at White Oak. Her mother’s father had too. The mill villages had their own schools, churches, stores, baseball teams, and police forces. For many families in Greensboro, Cone wasn’t just a company. It was a whole universe.3

There’s a Facebook group devoted to memories of life in the mill villages, and the prevailing sentiment is that Things Were Better in the Old Days when people worked hard for what they had and kids played outdoors and everyone went to church. Of course, the people who join the Facebook group and post nostalgic memes were mostly children or teenagers when Cone began to sell off its housing stock to employees. Moreover, they represent the employees and families who followed the strict rules of the company town. While church attendance may not have been explicitly required, it was “in every way encouraged by the mill management,” a 1913 profile of Ceasar Cone noted. Drunkenness and unruliness could cost a worker not only his job but his family’s home. In the 1920s, before the establishment of the nlrb, union activities could also result in expulsion from the kingdom of Cone.4

“Those who loved freedom too much or subscribed to different moral standards were not allowed to live in the villages,” according to an editorial in the Greensboro News & Record that ran in the late 1990s—and in the author’s view, that’s what made the village such a nice place to live. It’s a different type of nostalgia than the passion for blue jeans that the denimheads feel, though both groups can probably tell you about the “Golden Handshake” with Levi Strauss to produce all the denim for 501 jeans, and the fact that workers once wove so much of the stuff that Greensboro was nicknamed Denim City. Both groups invoke words like heirloom and heritage.5

The members of the mill village Facebook group seem to be mostly white, as are my own family members and their neighbors who’ve talked to me about Cone. It’s important to note how racial segregation was another structure of mill life. Black workers and their families lived in East White Oak Village. Sarah Maske of the Greensboro History Museum recently worked on a community exhibit about life at East White Oak. Cone was relatively early to hire Black workers in its textile plants, she tells me. Groundskeeping and maintenance jobs had been performed by Black men since the mills opened; by the early 1930s, East White Oak residents began to work production line jobs in the dye room, boiler room, and carding room. These were some of the most dangerous and lowest paid jobs, and all held by men; Black women weren’t hired for mill jobs until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, and they often worked in the white mill villages as domestic servants.

Despite these inequities, the East White Oak Community Center exhibit reflects a similar warmth toward the strong community ties that thrived in the mill village as those expressed by the Facebook posters. “It was always ‘close knit,’ ‘we took care of each other,’ ‘we knew everybody,’” Sarah said of themes that emerged through previously recorded oral histories and new interviews. The East White Oak school offered an education superior to what Black children were able to access at other public schools, and the mill village offered better healthcare too. People felt safe in East White Oak.

Nostalgia can be sentimental, even reactionary, but it can also contain a clear-eyed assessment of the tradeoffs that people have made. Fighting for racial and gender equality often meant giving up whatever comforts and security one had managed to obtain. And before either of these battles were truly won at Cone, the mills started shutting down. Greensboro thrives as a midsize eds-and-meds hub, but Denim City died out.

Cone Corporation still exists, as does Wrangler, also based in the city. Despite having offices in Greensboro, neither company operates production facilities in the United States anymore. Both are tiny corporate fragments within larger conglomerates and private equity structures, no longer independent companies in any sense. Greensboro, today, is a tiny pin on the mind-bogglingly complex garment and textile supply chain map, a middleman among middlemen. A single piece of clothing can have a twenty-thousand-mile footprint, Bob tells me, raw materials grown on one continent, flown to another for processing into thread and then into fabric, and then back across the ocean for cutting and sewing.

When my uncle worked at White Oak in the weave room, he said you didn’t dare wear ear protection, because of the names you’d get called by your fellow weavers. It wasn’t part of the culture, even though people went deaf from the noise. (No face masks either, despite the risk of brown lung from the lint floating through the hot air.) He recalled going out to his car in the parking lot at the end of third shift and knowing that his car started only when the lights came on—he couldn’t hear the engine turn over. It would take a whole day for his ears to recover. It’s that exact noise from the looms that the denimheads romanticize, according to Bob. Vidalia Mills will post footage of the looms on Instagram, and “they get all crazy about the clickety-clack sound of it. Part of it’s wood, and it just has a certain rhythm to it, and it’s very unique.”

Vidalia Mills could recondition the Draper looms, get them humming as loudly as ever, but they couldn’t recreate the knowledge of how to work them out of thin air. Bob tells me that the skill to run the looms is so specialized that Vidalia Mills hired former Cone employees to train staff, and some stayed on and work there still. Wages average about $18 an hour; the state of Louisiana observes the federal minimum wage of $7.25. Workers wear ear protection these days, and, since the pandemic hit, face masks, even though improved ventilation means brown lung is no longer a worry.

Vidalia Mills has 1.2 million square feet, 800,000 currently in use (White Oak was 1.6 million square feet). The facility used to be a Fruit of the Loom mill. Some of the former employees of that factory now work for Vidalia, too. Between the sunny social media and Bob’s genial conversation, I could almost be convinced it’s a little utopia, textile workers old and new passing down an American tradition. But if I were inventing a denim utopia, I would remind myself to ask for a little more. What would be best, collective ownership? An ironclad union contract? I remember something Sarah said: “If you talk to anybody about the Cones—‘the Cones are great. They took care of us’—it’s always very positive in terms of memory.” That’s how my grandmother felt too. Ideology aside, would workers today ever opt for the mill village system of paternalism if it were still on offer?

While I’m visiting my parents in North Carolina, I pay a visit to the Raleigh Denim Workshop and its retail space, dubbed the Curatory. The brand does a successful boutique business in selvage denim jeans, sewn from the last bolts produced at Cone, and also the denim woven on the old White Oaks looms at the new mill in Vidalia. The workshop and clothing store are inside a two-story red brick building on a street of two-story red brick buildings, an area that the local tourism board has dubbed the Warehouse District. A row of evenly spaced crepe myrtles and holly trees livens the staid brick expanse on one side of the street. On the other, Raleigh displays a series of denim flags on white poles that jut out from the rust-colored facade.

Inside, a young woman with close-cropped brown hair and a UFO bicep tattoo sits at a receptionist desk that doubles as a cashier counter. She is there to greet visitors pleasantly, offer masks and hand sanitizer as needed, and prevent customers from wandering into the Workshop instead of the Curatory. Raleigh Denim’s website proudly claims this is “a place that makes you curious as soon as you walk in the door. Right away, you hear the sounds of sewing machines, look left and see our jeansmiths in action.”

There are not any jeansmiths on display when I first enter on a Tuesday, though the entire workshop space isn’t visible from my vantage point. I can see the workstations where the vintage machines stitch Raleigh’s wares, as well as deep rows of industrial metal shelves and plastic bins full of folded jeans and more modern industrial sergers, set back from view and less impressively antique.

The woman at the desk asks if I’ve been there before, ready, I sense, to explain the wonders of selvage denim and heirloom equipment. I tell her about my interest in White Oak, Vidalia, the famous Draper looms. She smiles, I think, although she’s wearing a mask so I can’t say for certain.

A pair of men’s jeans made of the treasured denim, either the last of the White Oak stock or the new-old stuff from Vidalia Mills, run between $385 and $425. Other pairs, made of canvas or denim produced in Mexico, are a little cheaper, but none are under $200. Bob tells me he’s impressed with the prices Raleigh Denim Workshop can command; he sees jeans with Vidalia Mills denim usually in the $200–$250 price range. Gap has a line of jeans with Vidalia Mills denim that retail for $120–$150.

More of the Curatory’s square footage is devoted to assemblages of worn wood, old machine parts in glass jars, and spools of thread than to clothing and accessories. There’s a vintage guitar amp next to a fiddle-leaf fig tree, a metal scale weighing a paper airplane against two pinecones in an inscrutable moral judgment. Next to it sits a trucker cap printed with ginkgo leaves for $55. There’s no music playing, but there is an old piano in the middle of the store. A small brass plaque invites the customer to play a tune—“if you are good.”

Though there is clothing, jewelry, bags, and wallets for men and women alike, the space is calibrated toward the masculine. The Lodestone brand candles bear scents like Bonfire and Resin and Forest Hunt. Besides denim, brown leather is the most popular material, followed by the earth-toned canvas of a few sturdy bags. The walls are painted black, although the large windows let in enough light that the space still feels airy.

As I leaf through the women’s clothing rack (a tailored chambray dress for $425, an oxford shirt made of the most delicate white cotton for $225), two young men enter and begin to browse. Their outfits are simple but pristine, anchored by crisp white tees. One wears black jeans, black low-top Chuck Taylors, and a blue denim jacket. The other’s jeans are sandblasted to a pale blue, cuffed to show off space-age-looking orange and white sneakers. Their hair is shaped into stylish halos. As they look through the jeans, the woman at the desk asks if they’ve been there before. They haven’t, the man in the black jeans tells her, but they like limited edition things. The woman explains how every item in the store is numbered, each a unique object within its run. The jeans are even signed with the Sharpied mark of the jeansmith who sewed them.

I try on a pair of women’s jeans in the largest size they make, hoping they won’t be too small—Raleigh does not court the plus-sized customer, and I hover at the edge of this honorable distinction, depending on the brand. The two curtained dressing rooms are in the back of the store, by a brown leather couch and a reclaimed-wood-and-iron coffee table sitting on a muted floral rug. On top of the coffee table there’s a wooden box full of denim scraps—the bottoms of pant legs that have been custom-hemmed.

The jeans, which have some stretch, fit. Fit well, even. There isn’t a mirror in the dressing room; by design, it seems, I have to step into the faux living room to check out my reflection. As I’m contemplating whether the pants lift my rear as promised, the two young Black men leave the shop and two older white women enter. They are excited to tell the woman at the desk that they’re here from California, just visiting, just exploring, just saw the shop and decided to drop in. This leads the woman at the desk to explain about the specialness of the denim, about Cone and White Oak and Vidalia, about how the owners used to have a shop in New York before they moved back to Raleigh. I am robbed of the chance for the desk woman to tell me how good the jeans look and to convince me to buy them, which is for the best because I can’t afford them.

But then, what does it mean to be able to afford them? What is a fair price? How much of that $225 goes into the jeansmith’s pocket? As it stands, a pair of $225 jeans would send my checking account into the red. If not today, then when my next autopay bill hits. Of course, I could put it on a credit card, pay it off over a couple of months, and if I wore them twice a week for the next three years . . .

The loud voices of the California women and the lack of positive reinforcement from a sales associate help keep my impulses in check. I dart back into the changing room and remove the jeans. But I do make a purchase before I leave: a small cardholder for $18. It’s not a proper wallet, just a rectangle of leather with the company’s logo pressed into it sewn to a rectangle of Cone denim, open at the top for sliding in a few IDs and debit cards. I pay the woman at the desk and leave, tucking my money between the leather and the denim as I head through the lobby and back to the quiet street.

The tattooed shopgirl, the young Black trendsetters, the California tourists—I doubt any of them would feel they had much in common with the more conservative members of the Cone Mill Villages Facebook group. Neither do they have much in common with the original blue jeans wearers—gold miners and ranchers who bought the dungarees because they were cheap and sturdy. But this idea of work, preferably hard manual work, suffuses the denim with a certain magic. You worked hard for what you have. A hard worker made these jeans, and these jeans can handle hard work, in the case you should have to do some.

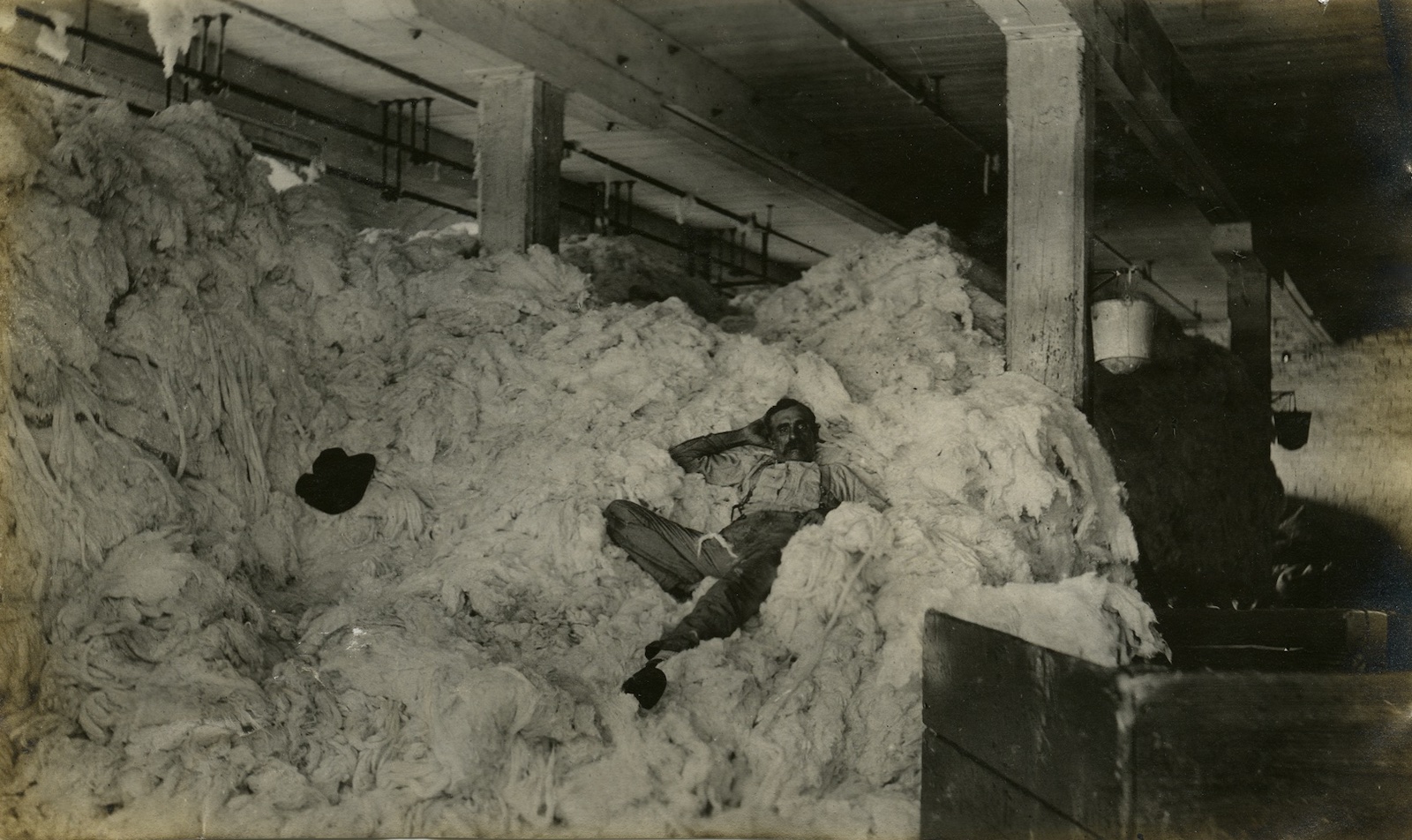

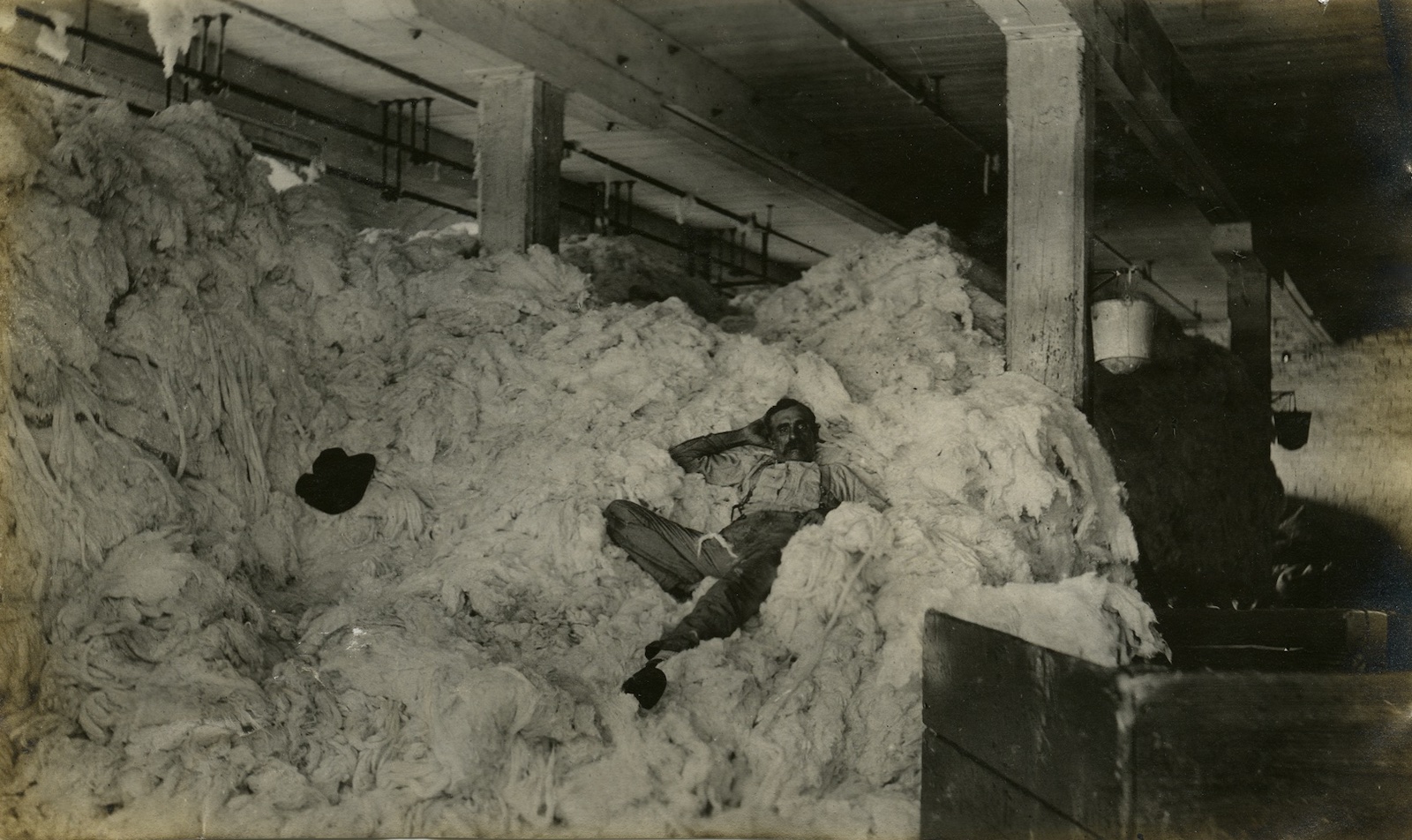

Worker resting on a pile of cotton, #346.

Worker resting on a pile of cotton, #346.

NAFTA is a dirty word in Greensboro. It stands for everything that led to the American textile industry nearly collapsing (though Bob tells me the death knell was really the creation of the World Trade Organization, which eliminated textile import quotas. Both happened in 1994, hence the confusion). It’s not hard to pinpoint what many former textile workers in Greensboro remember as the time when America was great, or at least had hopes of getting there: literally 1993.

The wearers of red MAGA hats and the wearers of blue heritage denim have something in common: we are unhappy with our current world, with its hopelessly convoluted supply chains, drop-shippers, subcontractors, and resellers. Mustachioed industrialists once celebrated technological advancements as proof of the superiority of Western, specifically American, civilization. Now that we know the byproducts of this progress are probably going to kill off most of humanity, save for a few billionaires on Mars and in New Zealand, it’s harder to view innovation and efficiency and endless growth as unalloyed goods. It’s harder to argue that the few are enriching the lives of the many, in the way that Cone loyalists will point at Christmas hams and literacy rates and hospital systems and parks. And even the nostalgia-posters are well aware that the apparent benevolence of the Cones was, at heart, a business strategy, a loyalty program for those employees who were willing to accept the terms and conditions that governed every part of their lives.

Where is Denim City now? In the early 2010s, Greenpeace and the documentary film The Price of Blue Jeans put a spotlight on Xintang, China, known as “the capital of jeans.” The town became so polluted that the Chinese government shut down textile production in the area, moving it to Changning in Hunan Province. Or maybe the crown should go to Juarez, where the denim branded as Cone (and sold by brands like Madewell) is now woven. Denimheads love the selvedge from Okayama Prefecture in Japan. Could it be Vidalia? There’s so much attractive about the Vidalia Mills story—good pay, good benefits, environmentally friendly. The jeans are more expensive, but a pair will last you twenty years. Still, it’s hard to imagine a boutique denim producer scaling up in a way that could have any meaningful impact on the textile industry at large. Greensboro is now making its own bid, at least to be Old Denim City: the Raleigh Denim founder and others have banded together to form the White Oak Legacy Foundation (W.O.L.F.), launching both a nonprofit dedicated to textile history and a line of denim woven on the last two known remaining Draper X3 looms.6

Those jeans might last forever, but, at $400, they’re still pricey for anyone working at a mill, even at the higher wages Vidalia pays. What garment does most represent the workers of the world today—hospital scrubs? Dickies and steel-toe boots? The cheap poly-blend black pants that are so often the retail and food service uniform, which you must buy yourself, topped by a T-shirt with the logo of the business, or a chef ’s coat, or a barista’s apron, the cost of which will be deducted from your paycheck?7

The pandemic seems only to have made the divide between those who wear uniforms and those who have sartorial autonomy starker. Ever since I started working remotely in 2020, I haven’t worn denim that much, or business casual either. I’m one of those privileged home-office workers who can type out most of my days in terrycloth and athleisure. But some days I think it’s too comfortable. Some days I think that just as the mill villages died out, just as the Piedmont textile industry atrophied, our current systems too will wither away. And then I think: whatever clothes you wear to do your dirtiest, hardest work, get them ready. You’ll need them.

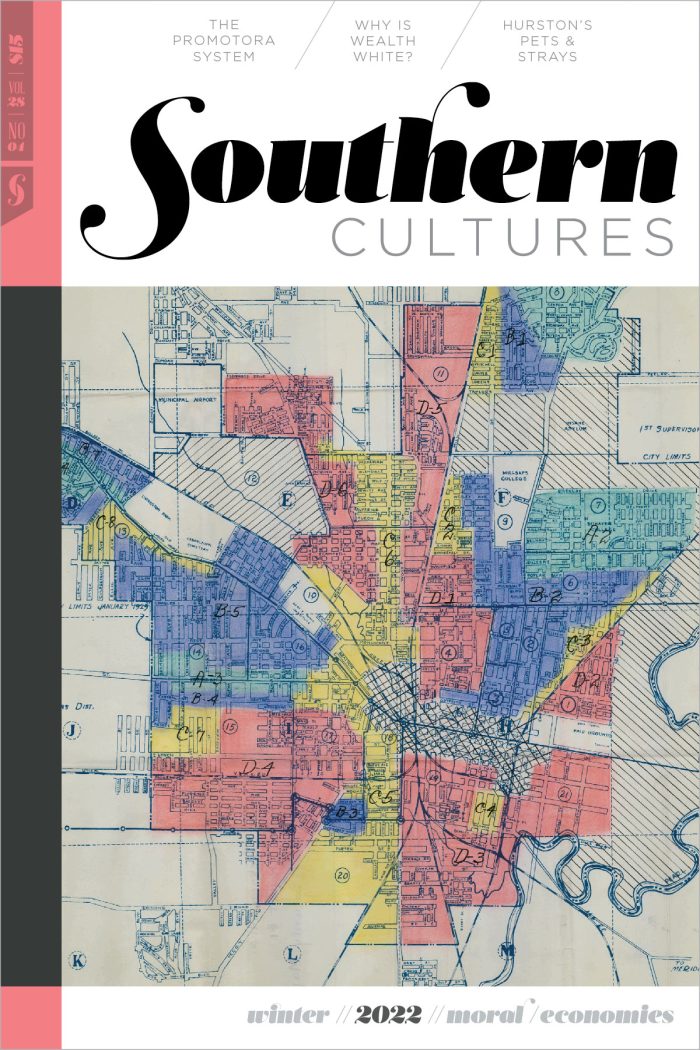

This essay was published in the Moral/Economies issue (Winter 2022).

Michelle Crouch is a writer, parent, housing organizer, and research administrator. Her work centers on the history of the Upper South and Mid-Atlantic regions, especially North Carolina and her adopted hometown of Philadelphia. Her nonfiction has recently appeared in Bright Wall/Dark Room, Shelterforce, and the Dear Hugo newsletter (https://buttondown.email/mcrouch).

NOTES

- James White, “Introducing Vidalia Mills—The Return of American Selvedge,” Heddels, May 13, 2020, https://www.heddels.com/2020/05/introducing-vidalia-mills-bringing-back-american-selvedge/.

- David Shuck, “Who Killed the Cone Mills White Oak Plant?,” Heddels, February 1, 2018, https://www.heddels.com/2018/02/killed-cone-mills-white-oak-plant/.

- Oral history interview with Caesar Cone, January 7, 1983. Interview C-0003, Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007), Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Published by Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/html_use/C-0003.html.

- “The Looms of Ceasar Cone,” Sky-Land Magazine, August 1914, 573–583, https://archive.org/details/skyland1913smit/page/572/mode/2up?view=theater; Bryant Simon, “Choosing Between the Ham and the Union: Paternalism in the Cone Mills of Greensboro, 1925–1930,” in Hanging by a Thread: Social Change in Southern Textiles, ed. Jeffrey Leiter, Michael Schulman, and Rhinda Zingraff (Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, 1991), http://libcdm1.uncg.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ttt/id/17376.

- Raymond Rogers, “Greensboro’s Mill-Village Paternalism Fostered Lasting Values—Modern Scholarship Disdains Paternalism. Maybe It Shouldn’t,” Greensboro News & Record, May 17, 1997 (updated January 24, 2015), https://greensboro.com/greensboros-mill-village-paternalism-fostered-lasting-values-modern-scholarship-disdains-paternalism-maybe-it-shouldnt/article_3e8cece0-e088-54b3-a9d5-209909e9bfca.html.

- W. David Marx, “Why Okayama? How the Japanese Region Became the Denim Capital,” Heddels, May 9, 2018, https://www.heddels.com/2016/02/why-okayama-japanese-region-became-denim-capital/.

- The clothing company Tellason introduced a pair of jeans made with Proximity Manufacturing Company denim (the for-profit arm of W.O.L.F) retailing for $395 in 2021, https://www.tellason.com/tellason-x-proximity-mfg-co-straight-leg/.