When I was five, my father explained to me that our city, New Orleans, could fill up with water like a fishbowl. Not long after receiving this surprising news, I heard the story of Noah’s Ark at Sunday school and understood it to be the most useful tale of all.

I was raised—home, school, and church—in the fancy Garden District, a village of sorts where everyone knew each other. My parents had just renovated a raised cottage, and we’d moved a few blocks from our modest shotgun home. It was the late 1970s, and their friends were Preservationists, white activists for New Orleans’s architectural heritage.

The raised cottage style was designed to allow for a full story of floodwaters to rise and fall under the house. Many of these elegant homes were built in the early to mid-nineteenth century by free or enslaved craftsmen of African descent. A wide, central flight of stairs led up to a deep front porch and then the front door. Rain and river waters could pool under the house amid a grid of brick pilings, then eventually drain. By the time my family moved into our new home—after two hundred and sixty years of levee-building to contain the Mississippi River and seventy-five years of pumping stormwaters and sewage toward swamps in the back of town—domineering engineering had conquered the urban mindset, memories of routine floodings had subsided, and the open space under our house had been walled in with siding, beams, and sheetrock to create a low-ceilinged apartment for tenants: ripe for deluge.

On May 3, 1978, while I was at school, an epic rain arrived. The wetness was far more than the city’s historic pumps could handle, and the streets began to flood. Carpool started early, and the kindergarten teachers formed a bucket brigade, passing each kid from one teacher to the next, like sandbags, to the cars. I was delivered with my carpool mates to our neighbor Lady Reiss’s Cadillac. Lady drove slowly for a few blocks, like a captain trying to leave no wake, but the car stalled out by the Keenans’ house, and we all took refuge inside. The afternoon stretched timelessly, accented by rounds of clapping thunder and board games in a sunroom surrounded by thrashing palmetto fronds. Then the rains stopped, and my dad glided up to the front steps in a canoe to paddle us home. Once there, I learned that our tenant’s apartment had flooded.

In the wake of that storm, I asked for a Noah’s Ark mural in my bedroom to help me sleep. My godmother, Mary Sue, obliged. There are no photos of the mural, only memories of falling asleep across by the floating zoo, the creatures braving extinction, with a rainbow and a dove with an olive branch above. My dad—a lifelong sailor who sold diesel marine engines—processed the flood pragmatically, digging in the backyard and building a bilge pump so he could drain the dank apartment swiftly if the waters were to rise again.

Two years later, we drove out to the 1980 grand opening of the Louisiana Science and Nature Center in New Orleans East. I stood mesmerized by a large model of a river delta. One slightly elevated end had a source of water, and the model sloped downward toward the lower end, where water pooled, drained, and circulated. The gushing water wove its way, cutting channels down the slope of silt. Toward the bottom, sediment would splay and then build up around a stream, forming a blotchy lobe. When the surface of the lobe grew high, the stream would slow and then, quick like a switch, change course to cut a shorter and more efficient path to the pool below. Over time, another lobe would form, and the pattern would repeat. This is my first memory of observing a physical model that represents a planetary pattern in smaller scale. The model illuminated how deltaic lobes build up over spans of time, and how hungry a river mouth is to reach the pool below.1

I was told this model related to the Mississippi River, yet there were no traces of humans in it. The model did not include earthen mounds built by the Indigenous nations that migrated to active floodplains here or the meeting grounds on the natural levee when the area was first called Bvlbancha. The model did not include levees and water-control structures, built under French, Spanish, and US American rule—often by African-descended people who were enslaved and incarcerated—to straightjacket the existing channel. The model did not include miniature forced labor camps lining this channel, drawing its waters for irrigation and commodity transportation, or polluting petrochemical refineries erected where those plantations once stood. The model did not contain the colonial settlement established around this corseted channel nor the nearby New Orleans East neighborhoods developed for first-time Black New Orleans homeowners from the 1950s to the 1970s, thousands of homes built on cement slabs on silt. The model did not reveal that, a quarter century later, those slabs would be broken, cracked from soil desiccation caused by pumping, and then saturated by floodwaters fifteen feet deep. The model did not include helicopters with ropes unfurled to rooftops or dead bodies in attics, when 80 percent of the city’s previous land surface swiftly became water surface in a man-made disaster called Katrina. But certainly the model could have predicted such a collapse.2

That collapse occurred in 2005, when I was in my early thirties. I had returned home after college and forged a life as a documentary filmmaker when a ferocious Category 5 hurricane was approaching. On an eerie Saturday in late August, I evacuated to Dallas and landed with a distant relative. She had a TV in her bedroom with the news running, but I didn’t watch because her comments made my head explode. On Monday night, as I was on the cusp of sleep, she came to the guest room door with big news. The Mississippi River levees in New Orleans had failed. And then she left. I lay awake all night long, imagining the rush—six hundred thousand cubic feet per second—pouring into the city. The arrival of the overdue apocalypse. I wondered who had died, where the rest of us would go, who I would be. This remains the most mournful night of my life.

Come morning, I learned my relative had misunderstood the news. Stormwater drainage canals and a shipping canal’s levee walls had been breached, but the river’s waters were still locked in place. The city was not completely gone.

Throughout that week, we died and we were rescued. We supported each other and we shot each other. We shared whereabouts and grief by learning to text on cellphones, and we watched our entrenched poverty and racism exposed on televisions around the world. We grasped that our lives and our city would never be the same due to this singular event, and we referred to historic hurricanes and floods, aware this was an old story in new clothes. We lost so much that cannot be repaired or replaced, and we gained an understanding of how catastrophe can transform a place. We had the highest nativity rate in the country—the percentage of people living in a place who were also born there—and we were refugees.3

My home had flooded, and on Friday I relocated from Dallas to Austin to meet up with a close collaborator and his husband. My godmother Mary Sue, the Noah’s Ark muralist, landed with her husband in arid Wyoming. My mom told me that Sue saw a fossil of a palmetto frond at an exhibit on the geological history of the region. Apparently, Wyoming once had a tropical climate, too—with crocodiles! Sue was reminded that all of these places are changing all the time, that maybe it was OK that New Orleans flooded, if you took the long view. This was the first and only time I have thought her callous, even cruel.

In the aftermath, New Orleanians knew that we were the canary in the coal mine of coming failures of twentieth-century infrastructure and urban policies in the United States. After projecting a romanticized past, everything turned, and we were now futuristic. A childhood schoolmate of mine made wildly popular stickers that summed it up: “So far behind, we’re ahead.”

I joined a film project, Land of Opportunity, about this phenomenon: how, through Katrina, New Orleans had become emblematic of the future of US cities. The director, Luisa Dantas, had grown up between Rio de Janeiro and New York City, with an international perspective on the American Dream, and she was curious about how people were seizing opportunities in the post-Katrina landscape and how these efforts would pan out over time. Her crew was documenting public housing residents fighting for their right to return to homes that had been fenced off and condemned despite suffering relatively little damage; Brazilian migrant workers laboring around the clock to rebuild the Superdome before the August 2006 NFL season; a Cuban urban planner leading charettes amid city-wide meetings where residents would circle around a model of their neighborhood and imagine how to “Build Back Better!”; a Creole urban gardener cooking with a cast-iron pan in a formaldehyde-laced FEMA trailer, while his family awaits permission to demolish their gutted home and rebuild; and a Black teenager who landed in Los Angeles for ninth grade—“Katrina, you did something!”—and then went on to UCLA with a Gates Scholarship.4

Despite the fact that the film was more about opportunities and conflicts in urban America than an exceptional New Orleans event, most film funders and distributors cited “Katrina fatigue” from the flood of media already in the market, and we struggled to continue. Eventually, we compressed and interwove eight protagonists’ lives over five years into a ninety-minute film, with the tagline: “Happening to a city near you.” We understood that most people in other places, at that time, didn’t know what was coming. This remains largely true today.5

On August 29, 2010, the fifth anniversary of Katrina, the film aired in Europe. The anniversary was a major milestone at home, among others throughout an intense summer. Eight weeks earlier, I had given birth to my daughter, Lulu. Eighteen weeks earlier, the Deepwater Horizon rig had exploded, unleashing an estimated 134 million gallons of oil in the Gulf of Mexico, followed by 1.8 million gallons of carcinogenic Corexit “clean-up” sprays applied underwater and on water and land surfaces nearby. I heard that an old friend, an environmental investigative reporter, and his pregnant wife were moving away due to the impact of Corexit on mammalian health, particularly for newborns. The landscape was too toxic.6

Cut forward nine years to 2019, to the banks of the Industrial Canal, when I stepped into a long canoe, held the gunnels, found my seat, and was launched toward the mighty Mississippi River—eek! I was joining the final leg of a program called River Semester, during which college students canoe down the Mississippi River, from its headwaters in Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. The plan was to do the trip from New Orleans to Venice, Louisiana, a.k.a. “the end of the world,” in four days and to charter a motorboat from the Venice marina to the Gulf and back on the fifth day. There were two canoes, and each canoe fit eight to ten people. I’d said yes to this adventure, but almost every New Orleanian I had told thought I was crazy, since we are taught not to touch the waters. I’d asked if it was even legal. The director of the program had gotten down on one knee to promise my daughter, who was then nine years old, that we would return.

I was participating in this journey in my role as executive director of the New Orleans Center for the Gulf South, an interdisciplinary regional studies center at Tulane University, and as a “river fellow.” Of many things the center’s team did during my tenure, my favorite was organizing immersive, site-based learning experiences that were open to scholars and the public. In 2019, the year of the River Semester canoe trip, we were collaborating deeply with two German institutions that had posited the Mississippi as an “Anthropocene River” and had funded a two-year study of the river as part of an ongoing investigation, grounded on several continents, of the human impact on earth. The international project was driven by the question of how to forge new forms of interdisciplinary knowledge production in the era of human-induced climate change. One gift in the ambitious Mississippi schematic was to support “river fellows”—scholars, artists, and activists—to join the River Semester paddlers for a leg or two.

The two-year study was culminating in a season of events and programming that started in Minneapolis and moved downriver to New Orleans, all timed to coincide with the River Semester canoeists’ schedule. The day they arrived in New Orleans via the river and carried the canoes up the wide steps on the levee by Jackson Square—arguably the oldest and best way to enter this city, or the very worst, if you were enslaved—the events commenced in New Orleans.

Over the next few days, two concurrent, time-traveling gatherings took place: a closed meeting of the Anthropocene Working Group, an international group of climate scientists seeking to formalize the Anthropocene as a new geological epoch, who were also funded by the Germans; and Slave Rebellion Reenactment, a three-day historical reenactment of the 1811 Slave Revolt, the largest known slave revolt in North American history, instigated by the artist Dread Scott and planned with numerous people and partners, including the center at Tulane, over several years. I toggled between the climate scientists, with their hockey-stick graphs and coring analyses from several continents, and taking my daughter to see the “Army of the Enslaved,” the all-Black group of reenactors who chanted “On to New Orleans! Freedom or Death!” as they marched from an upriver plantation, across a river spillway, through the French Quarter, and finally to Congo Square. Both the climate scientists and the Army were tactical and revolutionary; riding time scales cultural, racial, and geological; sounding battle cries for truth-telling.7

That weekend was followed by a dense week of seminars, public programming, and, as finale, a Saturday festival in an urban forest. Midday on Saturday, one of our gas-guzzling tour buses got stuck sideways across a road that winds along the river levee, two tires in a ditch off the asphalt plane. This road was the only route to the beloved annual festival. Hundreds of people blocked by the bus abandoned their cars and walked a mile atop the levee to get there anyway. And folks who needed rides were carpooled in golf carts, miniversions of our hobbled bus.8

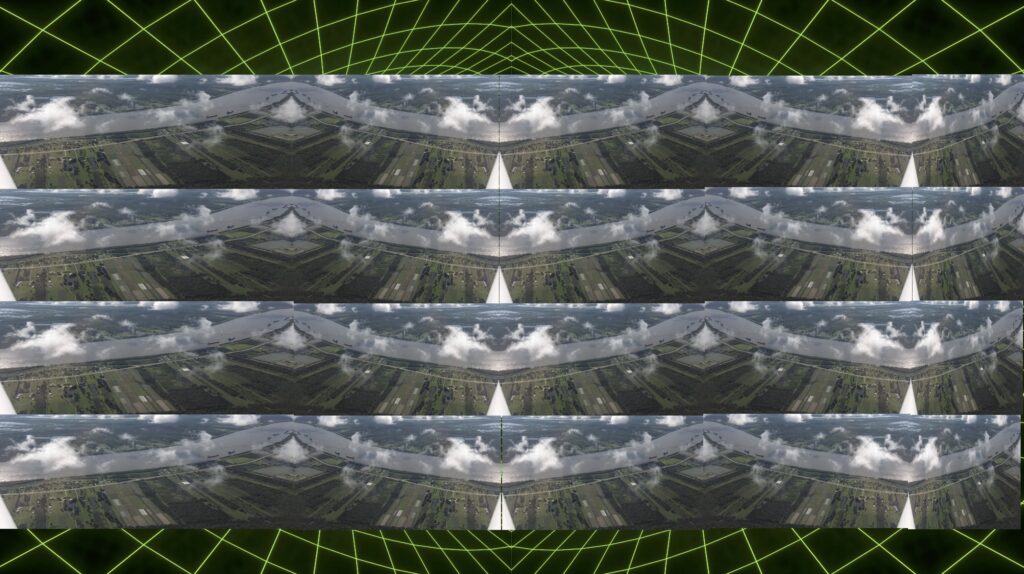

The next day, I was finally seated in a River Semester canoe and heading from the Industrial Canal into the Mississippi. Those in the bow set the pace, arms churning rigorously like wheels ahead of and behind me. Exhausted from the previous months, I considered disembarking. Yet I was exhilarated by a sense of transgression, disobeying a lifelong rule as we crossed the border of the banks and entered the river. At last, I fell in sync with the other paddlers. I was enthralled by the view, almost level with the river’s surface, and a profound reality: There were six hundred thousand cubic feet per second of water flowing with and around us, in a fairly narrow channel two hundred feet deep. I was carried by divine camaraderie, songs, laughter, and stories. We passed willow plants and petrochemical plants. We passed paddling ducks and swooping pelicans—descendants of dinosaurs. We passed tankers carrying fossil fuels, frozen poultry, and plastics around the planet, and we headed into daunting waves from their wakes.

Camping on the riverbanks at night, I felt like I had stepped into a nineteenth-century Harper’s Weekly etching. Around a driftwood fire on spongy silt, we talked about time. I confessed to the students that, for most of my life, the timeline on which I had understood this place was just a quick blip: the three centuries since French colonists had named it New Orleans. When I was their age, I could describe British feudal systems from the Middle Ages and Italian art patronage during the Renaissance, yet I did not even have a name for those same time periods here. More recently, I had been studying Indigenous and geological histories of the region and was slowly gaining a sense of the long durée, of a timeline that holds it all.

In my job, when we brought people together to learn from one another, often at sites related to cultural and environmental histories, I would hope we could imagine the future, but often what we were really doing was catching up to the present. So much of the built infrastructure our lifestyles depend on is hidden to the naked eye. Witnessing sites helps us understand our surroundings, across time. Visit a giant pile of refined sugar to consider slavery, diabetes, pleasure, and addiction; or a mound of radioactive phosphogypsum to contemplate that nitrogen-based ammonia fertilizer is produced—with radioactive byproducts—in Louisiana, shipped upriver and injected into agricultural fields, then drained back downriver and out to the Gulf, causing a “dead zone” there that is the size of New Jersey. This can help reality sink in and provide a refreshed foundation from which we can make decisions and act. I liked asking others, “In what timeline do you operate? In what timeframe is your imaginary?” I heard my friend Shana M. griffin ask: “When is your New Orleans?” And Monique Verdin: “What do the stars see when they look down at the Mississippi?” Under the stars with the River Semester students, we spoke of how extending the timelines of our imaginations, learning more and daydreaming and recreating how things worked before extraction reigned, may help us mitigate or even repair some of the damage that has been done.9

During the day, the paddlers sang together, in rounds. Somewhere along that chorus, it hit me how completely those of us who live by the river had given up on, or never even conceived of, personal access to its waters or hope for protecting them. I envisioned a blockade of boats spanning the river, Greenpeace-style, to block commerce and reclaim the waters from industry and capitalism. I finally understood that the Lower Mississippi isn’t a “river” anymore. It was and is a shipping canal for multinational corporations. A pipeline. As I heard architect and planner Dilip da Cunha say just this last fall: “The river is a colonial construct.”10

On our fifth and the last day of the River Semester journey, we reached the Venice marina and hired two motorboat captains to bring us to the Gulf. From the dock, I climbed onto a fiberglass deck and sat next to a friend from New Orleans who had joined us for the day and would drive some of us back to New Orleans in her car that evening. The boat captain cranked a rock radio station, the first recorded music I had heard all week, and we took off. The bow leveled, and we zipped down a small distributary. After a week of manual motion, the speed was astonishing. Never have I felt the power of fossil fuels so clearly: They make everything go faster. It was intoxicating to feel this Great Acceleration, full throttle.

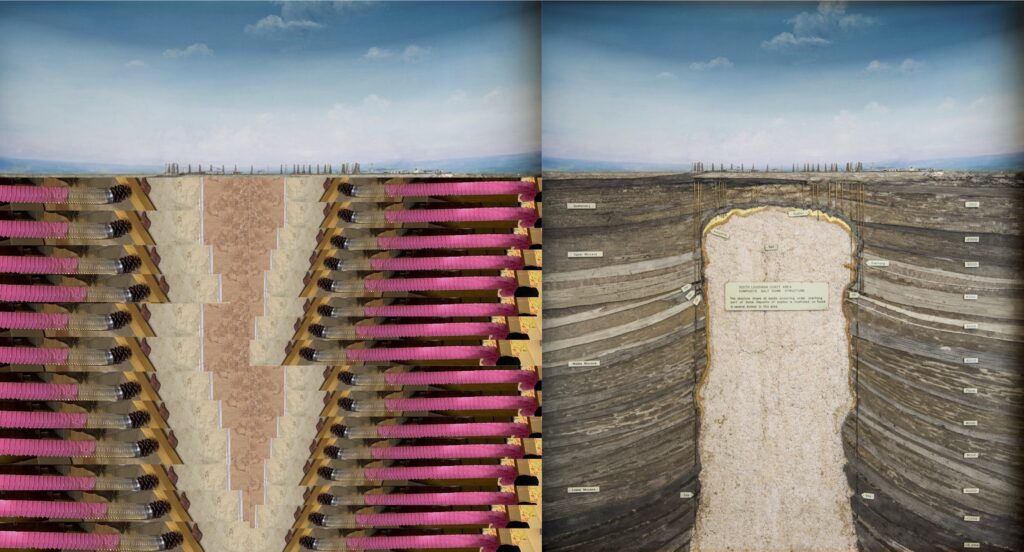

blatt einer palm

eneben dem blatt ist ein kleines insekt auf der sedimentaplatte zu finden

Wyoming/USA eozanleaf of a palm tree

next to the leaf a small insect can be found on the sediment plate

Wyoming/USA Eocene

Two years ago, I was invited to Vienna to contribute to a conference on music and race. I shared the story of “L’Union Creole,” an oral history project and spring concert series that our team at Tulane had co-organized from 2018 to 2021. The project reflected the diversity of living musicians in New Orleans, all influenced by African diasporic creative expression, and all impacted personally by white supremacy, late capitalism, monotonies of the reigning tourism and petrochemical industries, and COVID-19 chaos and climate chaos. One afternoon, I snuck away from the conference to visit Vienna’s Natural History Museum, which I’d heard was a treasure chest of Habsburg Empire loot. Across a room of wooden showcases, skeletal tableaus, and clusters of ancient bivalves, a tall palmetto frond beckoned from between two high windows. My jaw dropped when I read the marker: “Wyoming/USA Eocene.”11

I recalled Mary Sue’s exodus to Wyoming and her fossil encounter seventeen years prior. This palmetto, alive at least forty million years ago, before tectonic clashes pushed the Rocky Mountains skyward, reminded me that Earth is ever-changing. Louisiana may one day be a jagged mountain range, or a glacier or magnetic pole. I released my judgment of Mary Sue. I released my anger that everything is changing.

Once home, I began making sketches and sculptures about local, planetary, and cosmic time, grounded in Gulf South materialities. My anxieties about running out of time in Louisiana were salved by reading histories of human conceptions of time and gathering materials that make them tangible: circular hoops and spiral slinkies (seasons, recurrences), sailing lines and various strings (linear time, arrow of time), grains of sand and mesh fruit produce bags (quantum physics, space-time nets). I find the more I can touch time and make it tangible, the more I am able to stay light, creative, and agile. I see these artworks as tools for looking ahead and behind, for supporting playfulness, agility, imagination, to fight denial and stultification. We each build our survival kits and spells, and how we imagine and relate to time is fundamental.

I also started building synchronologies of river deltas around the world, frameworks that contain multiple chronologies in one chart, allowing a viewer to observe concurrent events and characteristics across continents. Upon seeing some of the sculptures and charts, a graduate student working in Pondicherry, India, near the Kaveri River delta, asked: “If you couch everything in this long durée, does this mean it’s not really worth taking any action?” I tried to explain: Seeing this big picture is the only thing that loosens me up from the paralyzing anxiety that being in constant climate precarity can cause, that helps me to live, that helps me to swim around and surface with any joy.

One of my favorite places to surface is the Nanih Bvlbancha, an earthen mound on the greenway between Bayou St. John and the French Quarter. The Nanih was conceived of by a group of Indigenous friends who collaborated with an arts organization, a golf course construction crew, an urban youth farm, and many more groups and peoples. They welcomed everyone to help. Two of the golf course specialists were Mayan men who knew how to build the stairs to the top, which provides a view toward the river and distant skyscrapers. Many of us contributed soil from places that are significant to us. I visit the Nanih frequently on my bicycle route to the gym. Perched there, I imagine the past and a future time when the river will have its way, once the levees break.12

As Dilip da Cunha observes, the water is not the problem; the idea of a flood is just a cultural condition because we think the river is a line that is supposed to stay in place, and we have designed infrastructure, real estate, and cities dependent on this human-imposed line that we read as reality. The flooding is a false construct, only possible if humans have come to believe the river is supposed to stay in one place and be a certain size. Da Cunha reiterates: The very concept of a river is a design “imposed on” a place. A place imposed on a place.13

The last time the Mississippi almost had its way was a century ago, during the Great Flood of 1927, when the river nearly jumped westward to the Atchafalaya River, quick like a switch. This took place at a juncture two hundred miles upriver from New Orleans, right across from the Louisiana State Penitentiary—a.k.a. “Angola,” a prison imposed on a plantation imposed on a floodplain. After the Great Flood, the Army Corps of Engineers built the Old River Control Structure complex, which continuously diverts one third of the Mississippi River to the Atchafalaya River Basin like an ongoing release valve, to fortify the status quo and prevent the Mississippi from changing course. It stands as a massive Brutalist-style monument to patterns of maintaining control and containment. I now see this monument as a time machine, too—locking the river in this lobe it wants to leave. Doing time.

The history of increasing control of the river and human bodies via levees and prisons parallels the history of increasing control of time. Today’s obsession with time management, busyness, and the technologies we’ve developed to measure time in smaller and smaller increments, now to the atomic zeptosecond, are considered scientific, but of course they are also cultural.

Our language is doing time, too. New Orleans has been the name of the place for the past three hundred years, with the river locked in place by the French, Spanish, and US Americans. When the river jumps course, the place will need to be renamed. New Bvlbancha? Does each placename specify only a phase of the life of that place, its matter for that time being?

In the Biblical story of Noah, in the scriptures of the Old Testament, in acrylic paint on my childhood wall, the ark is battling extinction. In this cosmography, the entire planet is water, with only Noah and his ark carrying humans and terrestrial animals. A friend sends me an online lecture by a British archeologist who collaborated with Indian marine architects and shipbuilders to build the biblical specs of Noah’s ark, as described on a clay tablet cuneiform dated 1750 BCE. It turns out the ark was a coracle, a circular ship form familiar to Babylonians, according to this tablet. Some say a circular boat leaves no wake; yet all movements move matter. I read the circularity as temporal, too. How facing extinction comes round and round. Will we decide to stop drilling for and burning oil?

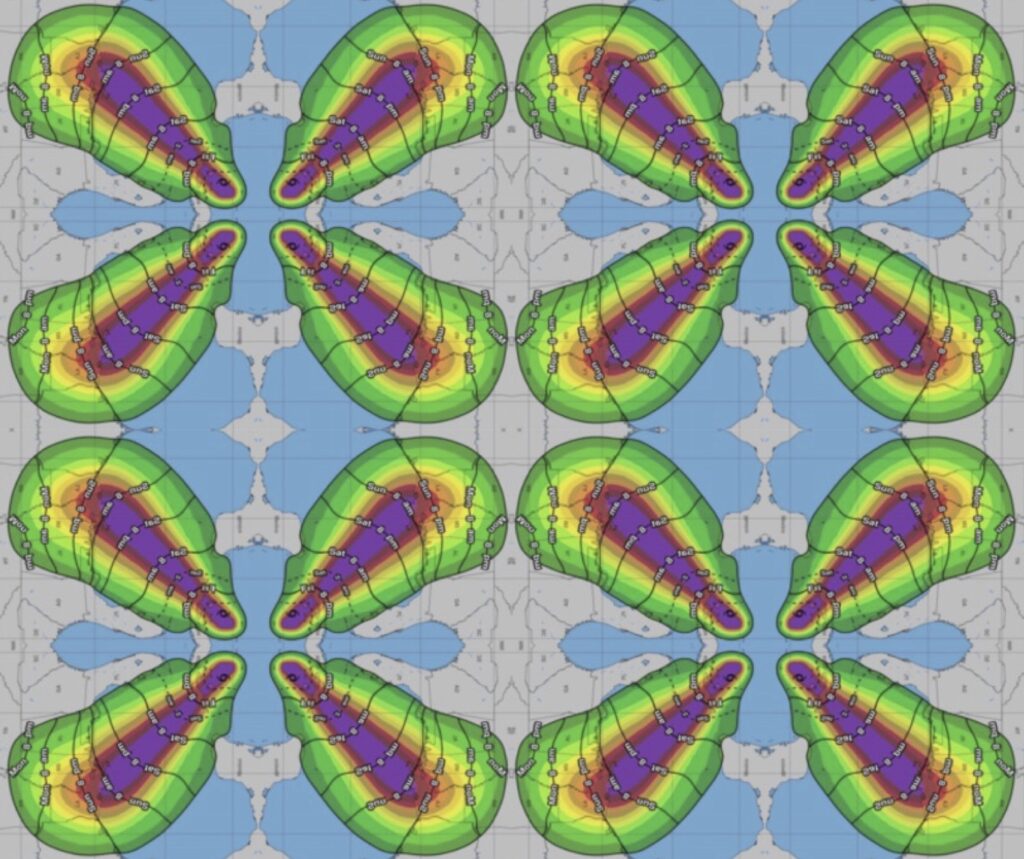

Does a model of the earth have a wake? In Jena, Germany, and Tempe, Arizona, in a collaboration between the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and Arizona State University, earth and social scientists have collaborated to build a Decision Theater, where digital planetary models quantify, illustrate, and speculate change over time. This comprehensive, interactive modeling is based, in part, on artificial intelligence that draws from new and existing models and curated streams of research data. In this cosmology, there are no simple answers. There are different interests and perspectives, and dozens of players can think through options together. “It looks like a war room, yet it is a peace conference,” explains mathematical physicist and MPIGEA director Jürgen Renn, and “could help reveal what a stable consensus might be.”14

Over the past twenty years in New Orleans, we have become experts in urban planning. We have regional plans: the Coastal Restoration Authority Plan and Greater New Orleans Water Management Plan and the Changing the Course competition plans. We have personal plans: for hurricane evacuations, street water flooding, boil water advisories, power outages, and cancer tumors. But we can’t plan our way out of the perils at hand. We can only mitigate, and we know each year may be the last. We have had twenty more years than I thought we would that night in Dallas, when I believed it was all over. Katrina wasn’t the end, but I do see it now as the golden spike—the emblematic signal of the beginning of a time period—of US coastal climate migration. The population of Greater New Orleans decreased by 20 percent between 2000 and 2015. And in the latest census estimates, New Orleans is the fastest-shrinking city in the United States.

When I fantasize about the river changing course, you may think me callous, even cruel. I am not going to dynamite the levees. But I have come to doubt that we can enter a new mentality, a less controlling and extractive way of living, if the river remains locked in its existing channel. I don’t know whether a change in human mentality will lead to releasing the river or the river changing course will quicken a societal shift, but I see the waters’ freedom and health as inseparable from our own. And I’m no longer attached to this place in its current form.

Meanwhile, we connect the local to the bioregional, national, planetary, and cosmic. We collaborate with and learn from friends, old and new, in a growing, decentralized movement of mutual aid and vital relations. We are present and in all time, in a village of sorts where people know their neighbors. We resist Indigenous erasure, white supremacy, surveillance, censorship, voter suppression, deportation, and authoritarianism. And we cooperate and create open schools to learn survival skills. Because despite the precarity, this planet is our home.15

On the twentieth anniversary of Katrina, I imagine the levees breaking and the water pouring in. I imagine a dove above, with an olive branch. The olive branch is today. The gift is time, and the time is now.

Rebecca Snedeker is an Emmy Award– winning nonfiction storyteller and the former James H. Clark Executive Director of the New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane University. Her notable works include Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas (University of California Press, 2013) and acclaimed documentary films such as By Invitation Only, Land of Opportunity, and Witness: Katrina.

NOTES

For their support with this essay, I am grateful to Andy Horowitz (in the beginning), Kira Akerman (at submission, the point of no return), and Casey Ruble (during the end times), and to Doug Miller for his support with the illustrations.

- In the 1970s, concern about wetlands damage and coastal erosion caused by timber and petro-chemical industry practices was rising. By 1980, the Louisiana Science and Nature Center, now known as the Audubon Louisiana Nature Center, was founded “to address an urgent community need for environmental education programming”; “Construction to begin at Audubon Louisiana Nature Center,” FOX8Live.com, May 2, 2015, https://www.fox8live.com/story/28958503/construction-to-begin-at-audubon-louisiana-nature-center/.

- As Jeffery Darensbourg notes, the placename Bulbancha/Bvlbancha is having a “resurgence,” including its use in the names of several Indigenous collectives and media publications; “Bulbancha” 64 Parishes, May 1, 2024, https://64parishes.org/entry/bulbancha. The intersection of human racism and engineering in the Lower Mississippi River region and, specifically, the use of African-descended enslaved and incarcerated people in building river levees is addressed in many recent works, including Justin Hosbey’s “Angola Prison’s Black Ecologies,” Environment and Planning F (2025), https://doi.org/10.1177/26349825241296077; Shana M. griffin’s “DISPLACED New Orleans” project, accessed June 26, 2025, https://www.displacedneworleans.com; John Bardes’s The Carceral City: Slavery and the Making of Mass Incarceration in New Orleans, 1803–1930 (University of North Carolina Press, 2024); the Historic New Orleans Collection’s Captive State: Louisiana and the Making of Mass Incarceration exhibition (July 19, 2024, to February 16, 2025), https://hnoc.org/exhibitions/captive-state; Kira Akerman’s film Hollow Tree (2023), https://hollowtreefilm.com/about/; and Lydia Pelot-Hobbs’s Prison Capital: Mass Incarceration and Abolition Struggles for Abolition Democracy in America (University of North Carolina Press, 2023) and “Lockdown Louisiana” in Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas, ed. Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker (University of California Press, 2013). The “plantation-to-pipeline” and “plantation to plant” landscape is described by many environmental justice–inspired organizations, activists, scholars, and artists from whom I’ve learned. Notable organizations include the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, Human Rights Watch, Louisiana Bucket Brigade, Louisiana Environmental Action Network, Healthy Gulf, Rise St. James, Taproot Earth, and many more. See Richard Campanella, Draining New Orleans: The 300-Year Quest to Dewater the Crescent City (Louisiana State University Press, 2023), and Andy Horowitz, Katrina: A History, 1915–2015 (Harvard University Press, 2022).

- Media coverage of the federal levee failures, urban flooding, and rescues portrayed African-descended people living in systemic poverty and government neglect normalized in New Orleans, yet considered shocking to viewers in the United States and around the world. Further, ten years later, the Urban League announced that the income gap by race in New Orleans had grown by 37 percent since Katrina; “An Unequal Recovery in New Orleans: Racial Disparities Grow in City Ten Years After Katrina,” Democracy Now, August 28, 2015, https://www.democracynow.org/2015/8/28/an_unequal_recovery_in_new_orleans.

- Luisa Dantas, Land of Opportunity (JoLu Productions, 2010). I believe the most important “Katrina film” that is not a documentary, but is as truthful as almost any, is Cauleen Smith’s Afrofuturistic, Cli-Fi film, The Fullness of Time (a cauleen smith video, with Creative Time, 2008).

- The majority of our funding came from the Ford Foundation’s former Metropolitan Opportunity program and through a broadcast deal with ARTE France. The film is now available through New Day Films and Kanopy.

- “Estimating Chemical Dispersant Exposure for Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Workers,” University of Minnesota Twin Cities, June 8, 2022, https://twin-cities.umn.edu/news-events/estimating-chemical-dispersant-exposure-deepwater-horizon-oil-spill-workers.

- The Slave Rebellion Reenactment project drew upon a lifetime of research by Leon A. Waters, director of the Louisiana Museum of African American History and Hidden History Tours and author of On to New Orleans!: Louisiana’s Heroic 1811 Slave Revolt (Cypress Press, 1996); Dread Scott, Slave Rebellion Reenactment, New Orleans, LA (Antenna, 2019), https://www.slave-revolt.com.

- The “Anthropocene River Campus: The Human Delta” included two-day seminars titled Claims/Property, Clashing Temporalities, Commodity Flows, Exhaustion and Imagination, Risk/Equity, and Un/bounded Engineering and Evolutionary Stability, each led by five to seven people who together brought local, regional, and international perspectives, as well as an evening public programming series that brought together local voices with participants based elsewhere. See “Anthropocene River Campus: the Human Delta, Anthropocene Curriculum,” accessed December 15, 2024, https://www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/project/mississippi/anthropocene-river-campus-the-human-delta/x. FORESTival is an annual festival at A Studio in the Woods, a residency program and eight-acre hardwood forest on the West Bank of the river that exemplifies the ecological movement here in New Orleans. The site is a former sugar plantation where one can still visit irrigation ditches. That year, we set up an “Anthropocene Base Camp,” with artifacts from the previous week and activities with Campus participants, such as tonal geologist Ryan C. Clarke, who took and discussed a muddy sediment coring with a small group of festivalgoers.

- “A Walking Discourse on Black Geographies & Indigenous Futures with Shana M. griffin and Monique Verdin,” presented by the Land Memory Bank and Seed Exchange and PUNCTUATE, with the Gulf South Open School, Mississippi River Open School, and the New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane University, April 16, 2024.

- Joe Underhill, “Navigating the Anthropocene River: A Traveler’s Guide to the (Dis)comforts of Being At-home-in-the-world,” Anthropocene Curriculum, July 27, 2020, https://www.anthropocene-curriculum.org/contribution/navigating-the-anthropocene-river; Dilip da Cunha, “Design Devices or Weapons of Colonizations,” paper presented during “Rivers and Powers: A Conversation on the Imaginaries, Materiality, and Culture of Urban Waters,” the keynote evening for the symposium “Geopoetics of Urban Rivers,” Franke Institute for the Humanities, University of Chicago, October 17–18, 2024.

- Rebecca Snedeker, “The L’Union Creole Spring Concert Series: Love and Life on the Cornerstore Dancefloor,” paper presented at “Transculturality: Music and Racism,” at the University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna, Austria, May 6, 2023. The series was a collaboration between the Neighborhood Story Project, New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane University, New Orleans Jazz National Historic Park, and Preservation Hall Foundation.

- The intertribal collective that instigated the creation of the Nanih Bvlbanha includes Dr. Tammy Greer, Ida Aronson, Jenna Mae, Ozone504, and Monique Verdin; Nanih Bvlbancha website, accessed June 20, 2025, https://nanihbvlbancha.net.

- Da Cunha, “Design Devices or Weapons of Colonizations”; Dilip da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent(University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), xi.

- “The Decision Theater, a Collaboration with Arizona State University,” Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, accessed June 16, 2025, https://www.gea.mpg.de/77053/decision-theater; Jürgen Renn, “Geoanthropology – a Science for the Anthropocene,” paper presented at “One Health and Geo-Anthropology in the Age of the Anthropocene,” Interuniversity Center for the History of Science and Technology, University of Lisbon, and NOVA School of Science and Technology, University of Lisbon, Portugal, December 13, 2024.

- Gulf South Open School, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.gulfsouthopen.school/; Anthropocene Commons, accessed June 20, 2025, https://anthropocene-commons.org/; and Monique Verdin, “Marooned Between Land and Water: Land Memory Bank and Seed Exchange,” Journal of Environmental Architecture 79, no. 1 (Spring 2025).