Longtime journalist Judy Walker worked as the food editor at the New Orleans–based Times-Picayune for about a year before Hurricane Katrina hit. Most of the newspaper staff, including Walker, evacuated to Baton Rouge and worked in a temporary office in the aftermath of the storm.

By mid-October, the newspaper returned to New Orleans and the food section started back up. Soon after, requests trickled in from readers for recipes that they’d lost in the storm—gumbos, oyster soup, mirliton casserole, stuffed crabs, and many more cherished, longtime family recipes that had been washed out from kitchen cabinets and personal libraries and drowned in Katrina’s floodwaters. So, Walker revamped her recipe exchange column, “Exchange Alley.” “The deal was,” Walker says, “if I couldn’t find the recipe in the [newspaper’s] files, the other readers would try to find it in their files.” And when recipes were located, Walker published them. “People immediately began requesting recipes they had lost in the water and telling me all these stories about how they tried to save their recipes.”

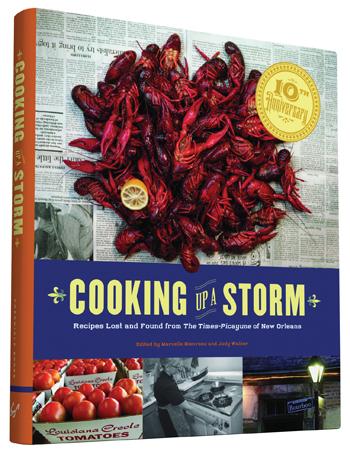

The reciprocal nature of the exchange column bloomed into a substantial collection of recipes reflecting New Orleans’s deep Creole and Cajun roots, and after six months, requests for a book rolled in. It took Walker and her coauthor, culinary historian Marcelle Bienvenu, three years to compile Cooking Up a Storm: Recipes Lost and Found from The Times-Picayune of New Orleans, a landmark cookbook that pieced back together a Katrina-fractured archive of community memory and taste traditions.

Cooking Up a Storm is a standalone hurricane cookbook. As a specialty subgenre, hurricane cookbooks are usually instructive, proffering advice for navigating the deprivations wrought by hurricanes, recommendations for meals made from shelf-stable ingredients, and hurricane season “how-tos” for the uninitiated. Works such as The Storm Gourmet: A Guide to Creating Extraordinary Meals Without Electricity and the digital Hurricane-Ready Cookbook are designed for the immediacy of hurricanes, and the authors try to meet cooks where they are in the post-storm moment: in their blacked-out kitchens with quickly thawing freezers and a bundle of dry and canned goods. The major takeaway is that, with the right amount of planning, anyone can endure—and thrive—in a major disaster.

But Cooking Up a Storm is an outlier, a lesson in true community exchange. The book distinguishes itself as a recuperative project offering up lost recipes, seemingly small restorations, after the massive collective suffering caused by Katrina. For foodways researchers, hurricane cookbooks reinforce the role that food plays in both basic survival and a more nuanced sense of place that roots us in community after a major disaster.

Walker reflected on Cooking Up a Storm, which was nominated for a James Beard Award in 2009, with Anna Hamilton, a writer and researcher who studies hurricane culture and foodways of Florida and the broader US South. Their conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for publication.

Judy Walker: The newspaper regrouped after the storm in Baton Rouge. In times of emergency at newspapers, you just do anything that’s required, including write obituaries of mass casualty events.

I did eventually start writing food stories. The first one I wrote about was about MREs, the “meals ready to eat” that the government was giving out to everybody. We got a bunch of them and tried them. I also talked to a bunch of people who were receiving them.

The newspaper returned to New Orleans, and you had to be there or lose your job. We lived with a friend for a while and then moved back into the upstairs of our house. It wasn’t damaged by the water. Then eventually, by Christmas, we were able to move downstairs and get our whole downstairs redone.

When we got the food section back up and running, I did a recipe exchange column, which used to be very common and [was] very old school. Before Katrina, a lady who lived in coastal Mississippi had asked for a recipe that she had lost in one of the hurricanes over there. The deal was if I couldn’t find the recipe in the files, the other readers would try to find it in their files, because our electronic files weren’t very good at that time. People immediately began requesting recipes they had lost in the water and telling me all these stories about how they tried to save their recipes: they’d cut these fragile pieces of paper out and . . . hang them on a clothesline to dry out. One of the very first people that sent in a request [also] sent in a reply to somebody else’s request, which was the lady in Mississippi who had lost her recipes. She had [the recipe] that this other person wanted. So, it was very reciprocal. It was right at the very beginning of social media. Newspapers were a traditional resource for recipes.

This goes on for several months. I did an occasional column that was on recipes people had sent me about things they had cooked when they were evacuated, recipes they cooked in the upstairs of their houses. Basically, how to cook without a kitchen. Eventually, there got to be enough of these recipes.

A lady named Judy Lane, who was living in this tiny community on the north shore called Talisheek, wrote me a letter and said: “I think you should put these recipes in a book. I lost my home in New Orleans and our rental and our cars and our business, and I broke both my legs in the storm and couldn’t get out. My husband set my legs as best he could, and we didn’t get out for two days.” I thought, “Here she is, she’s gone through all this, and now this is on her mind?” That day I went to the publisher and said, “We need to do this. We need to do this project.”

Marcelle [Bienvenu] and I started working on the project and told the readers we were going to do it. We asked, “What recipes do you want to see in it?” And we had all these weird coincidences happen. People would ask for the same recipe.

It took us three years from start to finish to get it all together. We realized it had a lot more reach than anybody thought originally. This was because [the American public] experienced Katrina too through their television sets and through all the millions of stories. Everybody who had a television set was traumatized by Katrina.

Anna Hamilton: It’s incredible to hear about the reach and the resonance of this cookbook across the borders of Louisiana and the South. I think I was surprised when I got it how big and comprehensive it is.

JW: We had all these recipes that people asked for, and we found [a lot]. There were recipes we could not find, and we would substitute something, and we put some of our favorite [recipes from the newspaper’s files] in there. We got to a point where we did try to fill in gaps with other recipes that hadn’t been asked for.

AH: I really wish that there were still recipe exchange columns. That feels like such a huge loss.

JW: It’s part of the whole loss of newspapers, really. When the New York Times wrote about our book, [they] referred to it as being kind of quaint, which it was at that time. [Exchange columns] were really a long-time staple. But in New Orleans, there are restaurants that look exactly like they did in the 1950s and ’60s. There are dishes that people still make that you can’t hardly find any place else in the country, like turtle soup. It’s a place where traditions hang on.

The other interesting thing that happened was the column got up and running in the fall. And so, people would discover that their recipes were missing because of Thanksgiving—they only make [certain] recipes once a year. They’d [realize they’d lost the recipe] and they would ask for it. So that really helped the impetus for it, because the holiday was coming up and they knew they wanted this one mirliton recipe.

Several people sent their favorite recipe that they had clipped out of the newspaper just as a general FYI. The recipe on page 141 for the “Spicy Cajun Shrimp” was one that a lady cut out from the newspaper and sent back in.

AH: It sounds like y’all have a big archive of some of these recipes and materials. Did you lose parts of your archives during the storm?

JW: No, the Times-Picayune then was really hurricane proof, and people would evacuate there with their families, with their pets. During Katrina, it was flooded, but not where the archives were kept. So, all that was still intact. And, of course, now the electronic files of all the newspapers across the country you can find online, but we do have plenty of recipes, [including] from the restaurants in New Orleans. I was just looking at “Stuffed Crabs Leruth.” Warren Leruth was this famous chef who had a very well-known restaurant on the West Bank. It had been gone for years, but he we had a couple of recipes in the archive from him. And then right across the page [from that recipe is] “Café Reconcile’s White Beans and Shrimp,” and Café Reconcile is still in existence. It’s a place to teach youth how to work in kitchens and have a career in kitchens.

AH: I’m curious if you got any requests that surprised you.

JW: What surprised me were things like two people asking for the same thing at once, or people actually having something, you know? That was a surprise, not as much the recipes, per se, as the way they arrived, or how they arrived.

AH: Do you have an example?

JW: Mrs. Francis Toomy’s “Fresh Corn and Shrimp Chowder.” The day that we got the request for it, we also received the recipe from somebody who said, “You should include this recipe, it’s so good you should put it in your book.”

AH: Were there any recipes that people asked for that nobody could find? That were lost?

JW: Yes. I know one of the gumbos—I think it was the seafood gumbo. We ended up finding a good seafood gumbo recipe and putting it in but knowing that it wasn’t exactly that one.

Several people wrote in to say they had lost their Picayune Creole Cookbook, and they were really sick about that because it would have notes from their mother and grandmother in it.

AH: New Orleans is such an icon in the food world—it’s such a well-known place with such a storied history and storied cuisine. Did that feel like a daunting project for you to come into this role [of food editor and cookbook author]?

JW: No, I knew a lot already from having been a food editor before. I belong to an organization called the Association of Food Editors and Writers; it was a national organization. I knew all these people through it, including the food editor at the [Times-Picayune], the one who retired in 2004. I’m from Oklahoma and Arkansas. My dad was in sales, and he would occasionally drive to New Orleans and come back with seafood, so I knew the reach of it from that. And then, I had just always liked making things from New Orleans. I learned a ton of stuff after I got here, too. I’ll never forget the [moving] guys. I was asking the guys who were unloading our moving van when we moved into our house in 2000, “What foods do nobody outside New Orleans know about?” He thought for a minute. He said, “Turkey necks.” He’s right. Nobody outside New Orleans know about turkey necks.

[When I started], I knew it was a very good job. I felt very, very, very lucky to be writing about food in New Orleans.

Anna Hamilton is the assistant director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. Hamilton’s research centers Florida’s foodways and the hurricane culture of the American South. Her forthcoming dissertation is a cultural history of hurricane parties in Florida.

Judy Walker is a longtime food journalist who served as food editor of the Times-Picayune in New Orleans from 2004 until her retirement. After Hurricane Katrina, she launched the “Exchange Alley” recipe column to help residents recover lost family recipes and co-authored Cooking Up a Storm (2008), which was nominated for a James Beard Award. Before moving to New Orleans, she worked as a food editor at the Arizona Republic and as a writer at Tulsa World.