This essay is part of our Shutter art and photography series. “Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers” is on view at the New Orleans Museum of Art, September 16, 2022–January 8, 2023, and “The Photographs of Ralph Eugene Meatyard” at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, October 1, 2022–January 15, 2023.

Because we can make and circulate pictures so easily, we forget how mysterious they are—records of light reflecting off something or someone or some place outside the camera in some past moment, tiny slivers of stopped time floating into the future. Photographs, as the critic and scholar David Campany reminds us, “confuse as much as fascinate, conceal as much as reveal . . . . They cannot carry meanings in any straightforward way.” The inherent particularity of the medium is always at war with any easy interpretation. In each picture, “there is a kind of madness.”

Two photography exhibitions on view in New Orleans through early 2023—“Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers” at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) and “The Photographs of Ralph Eugene Meatyard” at the Ogden Museum—provide radically different illustrations of the enigmatic qualities in the medium. At NOMA, a deeply researched and path-breaking historical survey focuses on specificity and the radical individuality of photographic portraits. Over at the Ogden, a Meatyard retrospective provides a dazzling opportunity to watch an artist experiment with techniques and forms that push back against photography’s particularity. These shows remind viewers that even with careful attention, many photographs defy what people think they know about reality. They startle.

NOMA’s “Called to the Camera,” an exhibition of more than a century of work by Black studio photographers, emphasizes what ought to be obvious but all too often is not: Black photographers and sitters have been present from the earliest years of American photography and have played an important role in the history of the medium. Curator Brian Piper has selected a collection of one-of-a-kind daguerreotypes, as well as cabinet cards, carte de visites, and other types of vintage prints, made by more than three dozen of the most successful Black studio photographers from the 1840s through the 1970s. These are presented along with a small number of works by contemporary Black photographers who have been influenced by this history.

The show begins with pictures of Black photographers working in Black-owned and run photography studios. Then it circles back to commercial photography’s origins in the booming portrait business of mid-nineteenth-century America. Multiple images of the abolitionist and writer Frederick Douglass are included here along with less famous subjects shot by known and unknown photographers. Particularly moving are a Civil War–era carte de visite of a very young Black sailor posed in his uniform in front of a painted backdrop that looks like a terrace outside an Italian villa, as well as a circa 1880 tintype of two older Black men armed with pistols and a hatchet and holding a document that may be a land deed. A parade of portraits of Black women, children, and parents stare out at viewers with all the particularity and beauty of their varied, individual selves. Contrasted with an ambrotype of a beautiful young Black woman, likely enslaved, holding a white child, these images make the show’s most important point: commercial photography studios, especially those run by Black photographers, gave Black people a chance to represent themselves.

Frederick Douglass insisted that photographic portraits could not help but reveal Black humanity, no matter the intentions of the photographer. In addition to sitting for more than 150 portraits, a practice that made him the most photographed American of the nineteenth century, Douglass also theorized about photography’s power. In the four speeches about the medium he made during the Civil War, he laid out his argument that the radical particularity of photography might be a powerful weapon against white supremacy and the racist visual caricatures circulated by blackface minstrelsy and scientific racism. He was also the first person to claim that the act of sitting for a portrait, of representing the self, could work as a symbol of and a metaphor for citizenship, the political act of representing the self.

Though the wall text for “Called to the Camera” does not explicitly make this point, Douglass’s ideas provide a through line as the show proceeds through a vast and mostly chronological exploration of work by Black photographers and their studios. The mystery here is not who made these images but who appears in them. Sometimes the captions reveal their names, but studios often labeled portraits with the names of the people who paid the bills. Sometimes they left no information at all. But even when the names of the subject are known, exactly who these people have been—their dreams and desires, their beliefs and fears—remains concealed, unavailable to the viewer, private. The only thing a photographic portrait communicates for sure is that this individual lived in this place and time, and that is enough. The pictures that these studios made were often conventional, following trends of time in order to satisfy clients. But the subjects were not types; they were individuals.

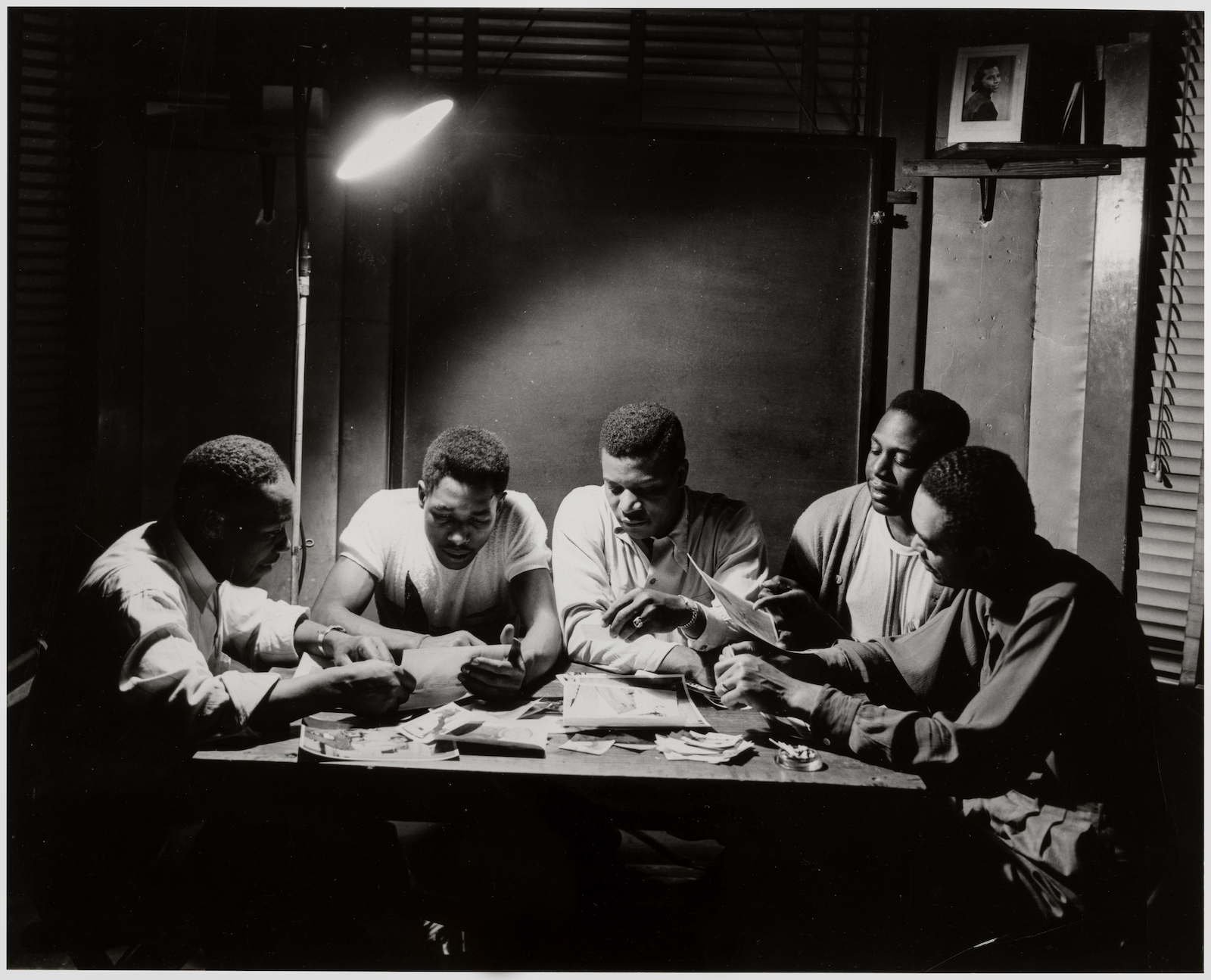

Images of Black flourishing and Black dreams abound. In Addison Scurlock’s portrait (ca. 1915) of a man with two dogs, the subject clenches a cigar in his teeth as he stares defiantly at the camera. He stands in field jacket, jodhpurs, and leather chaps and boots with a rifle in his arm as his dogs lay calmly at his feet, one on either side of a mess of birds whose many corpses hang from a string attached to a wooden posing stand. “Marvin Painting a Self-Portrait,” an image from the Morgan and Marvin Smith Studio (ca. 1940), foregrounds the act of self-representation and the multiple possibilities of Black image-making. From both sides at once—the angle the camera faced and that scene as reflected in a large mirror—a commercial photographer who was also an artist renders himself. If he also made the photograph, then this is a self-portrait of a self-portrait. An image of the photographer Gordon Parks (ca. 1946) engages in a similar layering. Parks, an important Black photographer who worked for the FSA photography project and Life magazine, poses for the Smith brothers in the successful studio they owned and ran in New York City. In Memphis during these years, the three Hooks brothers—Henry, Robert, and Charles—had their own successful studio, too. They also took their cameras into the streets, making a striking 1955 photograph of a man and woman in athletic attire grasping arms across the hood of a late-model car.

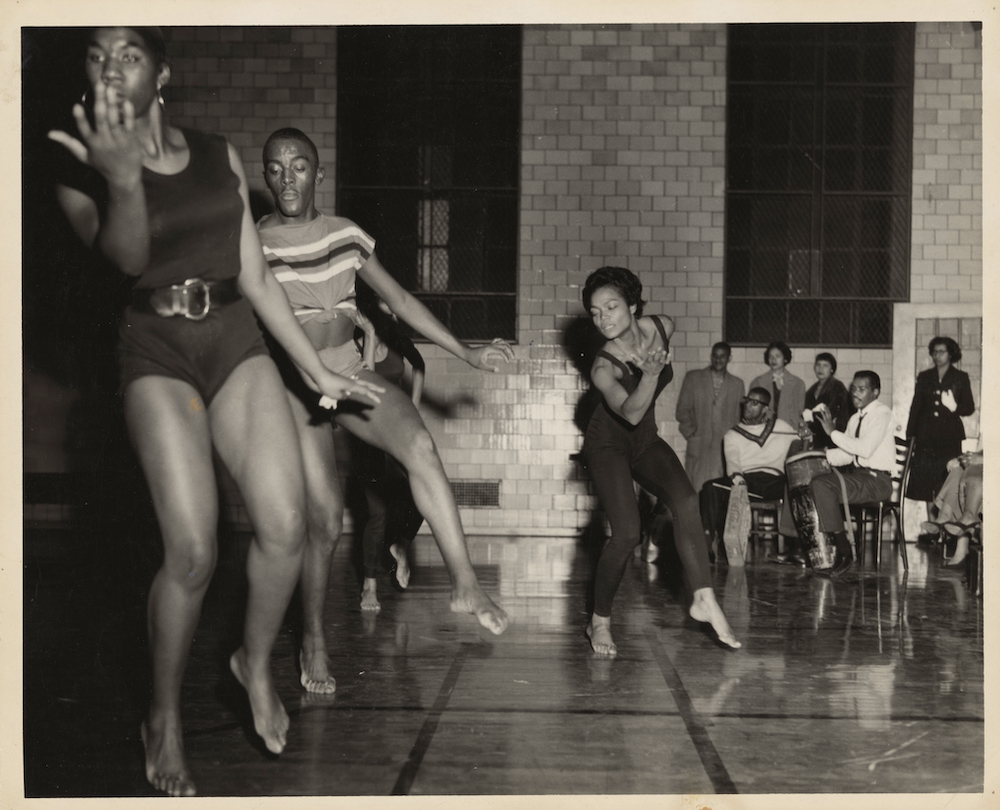

As this picture makes clear, Black studio photographers worked outside their studios, capturing important events and everyday scenes. Arthur P. Bedou, who ran a studio in New Orleans, photographed the packed stands at a Xavier University football game in 1936, where a huddle of wimple-wearing nuns sat in the center of a sea of well-dressed Black fans. Austin Hansen, who ran a studio in New York, captured Eartha Kitt, her feet bare, her torso twisted, and her left leg and right arm extended, as students try to copy her moves in a dance class she taught around 1955 at the Harlem YMCA.

Black studio photographers had to be entrepreneurs in order to stay in business. But they did more than make a living. They created a visual record of Black American life through their portraits and images of organizations and events. And they challenged dominant white ideas about who Black Americans were and could be in Jim Crow America. NOMA’s exhibition provides a rare chance to see the work of these photographers together in one place.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, a photographer based in Lexington, Kentucky, made art that plays with what art critic David Campany has called the madness of photography. Deeply influenced by a love for literature and language and an interest in Zen Buddhism, Meatyard was part of a creative and ambitious network of Kentucky artists, including writers like the monk Thomas Merton, the farmer Wendell Berry, and University of Kentucky professors James Baker Hall and Guy Davenport, as well as photographers and fellow members of the Lexington Camera Club like Cranston Richie, Guy Mendes, and Van Deren Coke, who also taught at UK. Between the mid-1950s and the early 1970s, despite working full-time as an optician and running his own business, Eyeglasses of Kentucky, Meatyard somehow managed to produce over 5,000 prints from 18,000 negatives. He used the camera, as his friend and sometime teacher Coke put it, to render “something of the world we feel but rarely see,” it’s weird, unknowable, and contradictory character.

The Ogden show divides Meatyard’s photographs into four categories: Romances, Portraits, Abstractions, and the Family Album of Lucybelle Crater. With one exception, examples from multiple bodies of work are exhibited together, enabling viewers to see how Meatyard experimented over time with the genre of family snapshots, ruins as a kind of stage set, the use of dolls and masks, reflections in glass, water and mirrors, and slow shutter speeds.

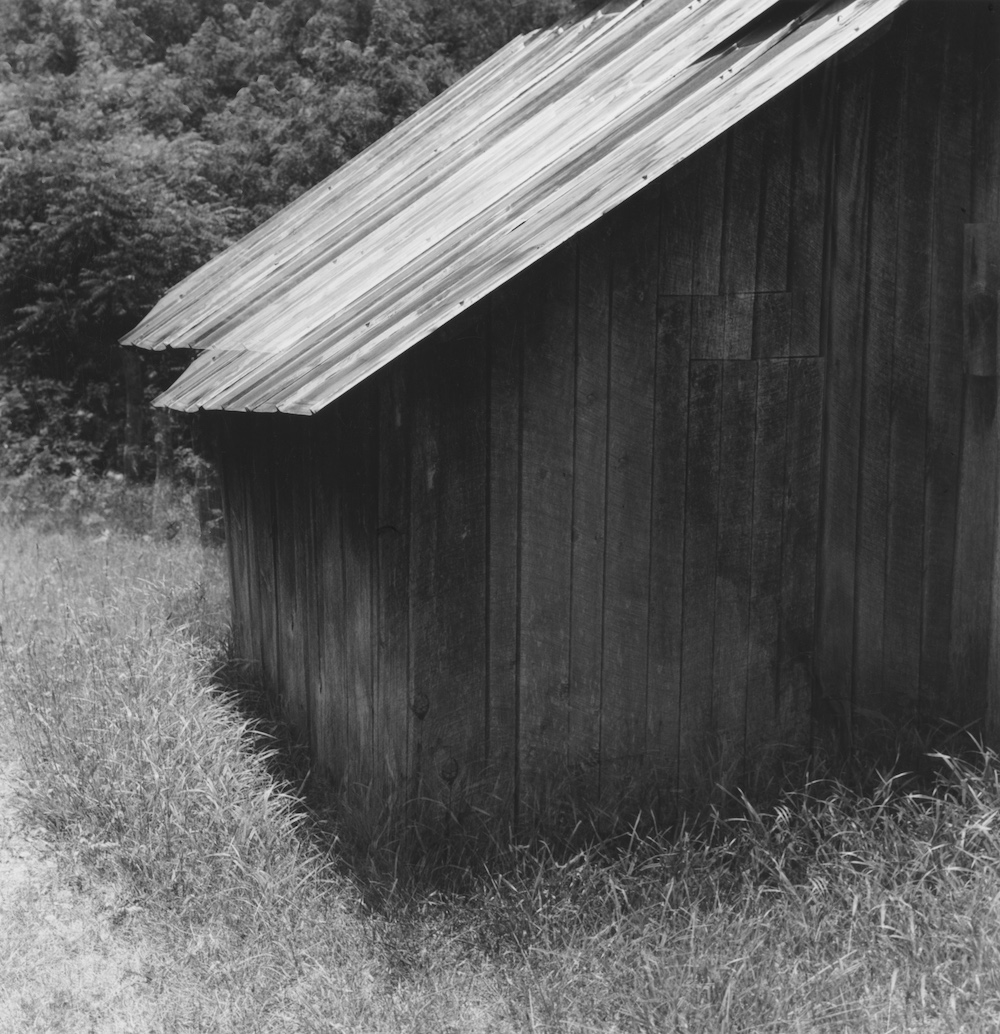

Many of Meatyard’s images feature his wife Madeline Meatyard and his children Michael, Christopher, and Melissa posing in ruined houses or other structures, or in overgrown landscapes. In a photograph from the mid-1950s, a giant ripped black curtain, pinned back from what was once the #10 loading dock of a tin warehouse, creates a dramatic frame around three sides of little Christopher. Meatyard’s son perches in profile with one leg cocked on a narrow ledge against a wall covered with fake brick siding that blocks the former doorway. There must be some reason the boy is there and something inside the warehouse whose metal wall looks melted where trucks have smashed against it, but all this photograph gives us is flatness, a strikingly detailed surface.

In a 1958 photograph of Madeline, also untitled, Meatyard’s wife stands on the right behind a screen door that cuts off and frames most of her torso and face in a vertical panel while the glass in the window on the left reflects an image of a tree and another building, probably a barn. In this way, the architectural elements of the window and door transform common subjects of family snapshots—a spouse and a yard—into something else entirely, pictures in a surreal gallery. A 1959 photograph titled “Cranston Ritchie,” featuring Meatyard’s friend and fellow photographer, produces a similar magic, a simultaneous particularity and abstraction. Ritchie, who lost his right arm to cancer and wears a prosthetic, stands to the right of a mirror on a hay-strewn floor, against a mottled wall in light that suggests some of the roof might be missing. To the left of the mirror is the torso of a mannequin dressed in a slip held up by one shoulder strap. Posed together, Cranston and the mannequin play a couple in another Meatyard riff on the genre of family photographs. As the picture unfolds across a flat, horizontal plane, the mirror functions like the blocked doorway in the image of Christopher at the warehouse, gesturing at, yet not granting access to, some alternate, interior space.

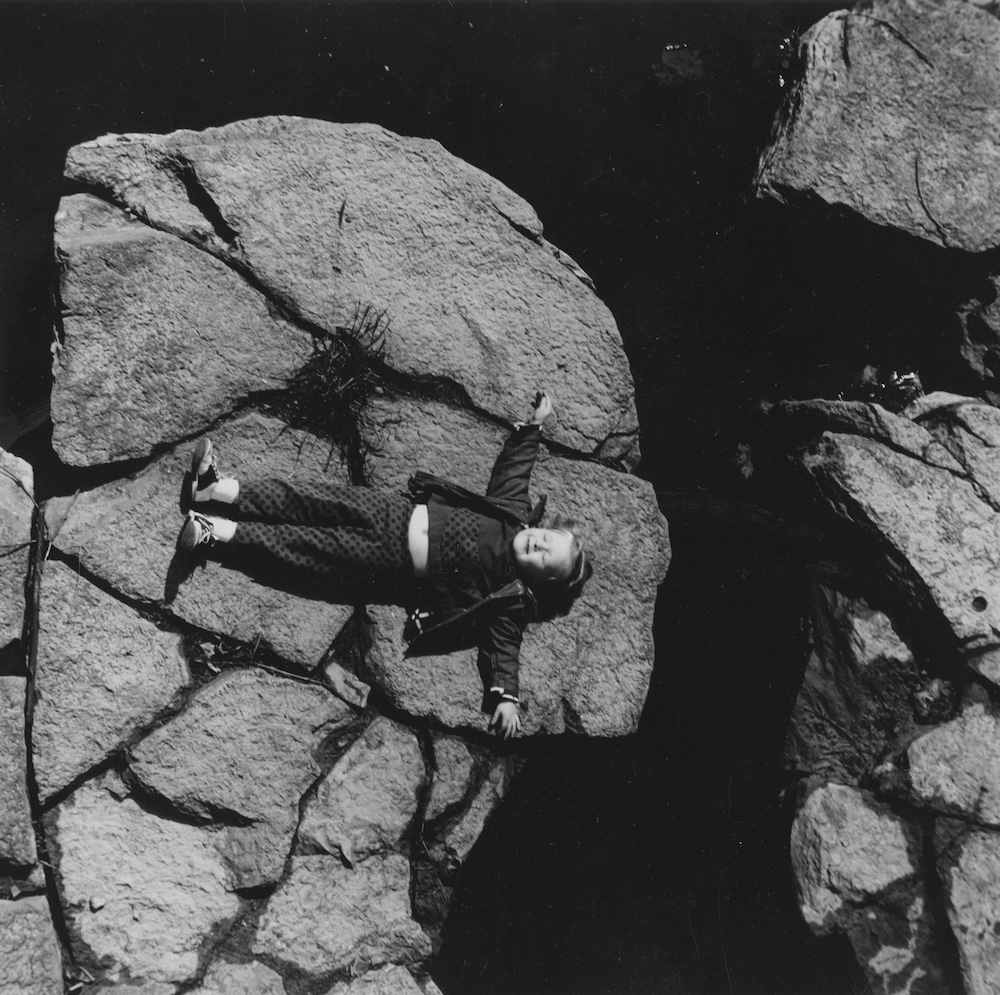

A 1961 image of Meatyard’s youngest child creates its own juxtaposition of flatness and depth. Meatyard captures Melissa from above as she lies on a fractured flat-topped rock with her arms outstretched, her body forming a sideways “T” that makes it look like she is falling. Just past the rock’s edge, mysterious depths beckon. Somewhere down there a bottom must exist, but in the space between the rock where Melissa lies and another fractured rock on the right it is simply too dark to see.

In the early 1960s, Meatyard began to incorporate dolls and masks into his work. In a 1962 photograph, one of his sons, probably Christopher, sits on a rock in a stream wearing a rubber mask that gives him huge ears, a bald head, and a blank face. Below him, a waterfall flows into a pool where one naked doll stands with arms outstretched and another floats on the surface. Today, Christopher Meatyard manages the family archive, and he has said that his father used masks he bought at Woolworth’s to “depersonalize” family members. Like black & white film and the title “untitled,” Meatyard’s masks add their own layer of formal abstraction. They deflect any easy understanding that family members and friends are playing themselves. And they foreground Meatyard’s theatricality, his staging of enigmatic scenes of his own making in the ruins of what were once flourishing agricultural communities in the rural hinterlands near Lexington.

Beginning in the late 1950s, Meatyard began to make more abstract photographs alongside his staged scenes of family members and friends. His first abstract series “Light on Water” is a collection of pictures of sunlight on the surface of the water in ponds, rivers, and streams. About a decade later, he created a series of sublime photographs of rural Kentucky landscapes he called “Motion-Sound” by employing double exposures—taking one image and then moving his camera slightly before shooting another one on the same frame.

Meatyard produced most of the pictures in his final and perhaps most enigmatic body of work, “The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater,” a meditation on family, time, and identity in the form of a photo album, after his 1970 diagnosis of terminal cancer. In each of the sixty-four photographs in the series, two people pose in suburban settings. Each one wears one of the same two masks, and the captions identify both as Lucybelle Crater. In all but one, Meatyard’s wife Madeline wears the same “hag” or old woman’s mask. She is joined by another figure—Meatyard himself or other family members or close friends wearing the other mask. By refusing the way collections of family pictures mark the passage of time by showing the same people at different ages, Meatyard creates a strangely eternal album of the people he loves.

Since his premature death in 1972, Meatyard has remained something of a photographer’s photographer, admired by artists, critics, and scholars. But he is not as well-known as he should be, given his pioneering use of the now-ubiquitous technique of having photographic subjects play roles rather than represent themselves made famous by later artists. The Ogden’s photography curator Richard McCabe has mounted a beautiful show that should bring Meatyard to a wider audience.

Grace Elizabeth Hale is Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia and a 2018–2019 Carnegie Fellow. She is the author, most recently, of Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture (2020). She has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post, Slate, American Scholar, and Southern Cultures. Her new book, forthcoming in 2023 from Little Brown, is In the Pines: A Lynching, a Lie, a Reckoning, a history of her grandfather, a Mississippi sheriff, and white Americans’ inability to reckon with the history of white supremacy.

Header image: Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Untitled (REM.0408.Y), 1968–72. Gelatin silver print, 8 x 10″. Collection of the Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery.