The clay knows the hand.

The land knows the feet.

The souls know the land.

Salt water flows in my veins, and I can recall my first taste of the Atlantic Ocean at two years old. I grew up hearing stories of how a six-year-old boy and girl, my maternal grandparents, met on a sandy South Carolina road and first experienced the spark that created my extended family. On this same road, Hurricane Hazel would one day claim Aunt Nette’s beach house, which she, the family’s matriarch, had proudly built in the all-Black resort town. Undeterred by that loss, that same boy, now grandfather and patriarch of the family, would awaken the whole house—sometimes neighbors too—and start a journey at 4:00 a.m. on a whim. We would all pile with our pillows into the wood-paneled station wagon and head for Atlantic Beach.

We were beach people, but we were not from the beach. I was a child of the beach only in that I knew how to dance on sand, eat crab, and ride waves. We would return there, sleeping three or four to a bed in Black-owned hotels, visit the Black dentist’s widow who stayed for weeks, go to the arcade to flirt and groove, and, over the years, bring the cremated ashes of our own, including my mother.

We were beach people, but we were not from the beach. I was a child of the beach only in that I knew how to dance on sand, eat crab, and ride waves.

Years later, some of us would return to take photos of our children with the town’s historic sign, which proudly declares Atlantic Beach, South Carolina, as the “Black Pearl of the Grand Strand.” But we had never truly lived there. To the coastal Black world, we were outsiders from the Midlands who would come to visit the sea and then return to the center of the state, where we bought fish for Friday’s dinner at markets rather than catch it ourselves.

So when my mother took a job as an administrator at a school on Hilton Head Island, the “beach people” (my mother and I) did not immediately become locals, but remained outsiders who were now island residents. Moving at the age of seven to Hilton Head Island, almost two hundred miles away, was a monumental shift. It was intrastate, yes, but the coast was culturally a universe away from the capital city of Columbia. We spoke differently, as we were from the “City South.” We were not Gullah or Geechee by birth, but we would soon become city southerners wrapped up in Gullah love. We would be welcomed.

Over time, my otherness shifted. I began bonding with the land and the people—and the land and the people of the Lowcountry are intrinsically tied. I learned to move in that land and was drawn to her mysteries most of all. My mother screamed when she saw a black snake on our back porch, but I was intrigued by its flesh, its rhythm. I would pull the prehistoric horseshoe crab by the tail to make designs in the sand with her feet. The dead jellyfish who hadn’t made it back out to sea was subject to my dissecting sticks. I would feed marshmallows to the alligator who lived in our neighborhood lagoon, and I somehow survived scratching its back with a long branch, acts I now know to be dangerous and extralegal. (I was nine and things were different in 1984.) I ate blackberries picked from wild bushes, ran from trees that seemed to sprout worms in the spring, and dug fossilized crustaceans from white sand earth. I practically lived with a Gullah family that my mother and I befriended. I remember being regularly told to watch out for snakes in the brambles and, once, hearing how somebody put a “root” on somebody. At that age, I don’t remember anyone calling anyone Gullah or being particularly concerned about the difference between the way I spoke when at Helen’s house on Hilton Head Island and the way I spoke at my grandmother’s house in Columbia, on the mainland.

I began to realize that I lived within a cultural heart of Gullah Geechee people at the age of nine, during a trip planned by Emory Campbell, longtime family friend and the former director of St. Helena Island’s Penn Center. As the folk say, he knew me from before I was born. I recall an overcast and humid sky and sitting in the back of a motorboat with a red life jacket pressing high under my chin. The motor was burring loud in the salt water, spraying my face. I had no clear idea what we were doing. We were in a boat, having an adventure on a neighboring island. Everyone looked somber. Grave faces, gray skies, salt water, opaque journey. And then we landed on Daufuskie Island. Dark brown male hands helped pull my smaller brown hands ashore. People gathered and Emory Campbell delivered the words. I don’t remember many of them, but he said something about land loss and culture and hotels and gated neighborhoods like the ones on Hilton Head called plantations, where Black people worked as maids and cooks on land they had once owned but couldn’t afford anymore. He also spoke of the people across the water, brought here against their will to toil by force and survive by choice. Those gathered around me looked pensive and mournful and determined.

I was determined to remember. And I did.

We ate Frogmore Stew (a Lowcountry boil of crab, shrimp, sausage, new potatoes, and corn) and drank red punch from paper cups. Over food, when people stopped talking about land loss and started laughing into bowls, I stepped away from the group. I walked a short distance down a sandy dirt road, flanked by live oaks and Spanish moss. It was an island and the road ended at the water. (If you picture a still from Kasi Lemmons’s Eve’s Bayou, or Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, or Beyoncé’s Lemonade visual album, or a paragraph from Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day, or a magical realist photograph by Allison Janae Hamilton, you’ll have some sense of that moment.) The water was gray, with a base of fertile earth that made it impossible to see to the bottom. I looked out and thought about who was looking across the sea at me. I thought about all the souls who had touched Daufuskie. I thought about Mr. Campbell telling us to remember how important this place is—sacred. Before then, I had associated the word sacred with church buildings. In my childhood belly, I knew at once that my days in blackberry bushes and sitting between Gullah knees to have my hair combed—these things, that island, those trees, that water—were all sacred. I was determined to remember. And I did.

I became mesmerized by the marshes at sunset, grasses emerging at low tide, golden, sometimes wind-bent, sometimes erect in the humidity. If it had been permitted, I would have stood, barefoot, calf-deep in the muck, searching for pearls in the oyster beds. In my nine-year-old dreams, I believed I could shape-shift into a mermaid, diving over and over into the crest of the smaller waves, arcing, toes in the salty air, fingertips touching sea-bottom sand, pelicans overhead, dolphins in the near distance. I yearned for gills to breathe at the bottom of this murky, brown coast. I yearned to find something, a message, a marble, a button, a bead, from the ones who didn’t make it. The trees too were my sanctuary. There seemed to be stories in their understory, memory in the moss, ground truth in the loam, hidden worlds in the branches I’d climb.

In my childhood belly, I knew at once that my days in blackberry bushes and sitting between Gullah knees to have my hair combed—these things, that island, those trees, that water—were all sacred.

Gullah people see these woodlands and waterways as sacred. A Gullah Christian in search of salvation may be directed by a church elder to go seeking in the wilderness for the will of God, to await the presence of “Grace” in the quiet of trees and the land of dreams. Perhaps a white egret would rest in a pine, majestic, signaling the “Holy of Holies” or the arrival of a beloved ancestor. Many a Gullah grave is set to face the water so the soul can fly home to the Motherland or to heaven’s rising suns, or both.

For many years I have considered the moment on Daufuskie Island, at the meeting place of land and water—perhaps one of the first footfalls of disembarking Africans not killed by the Middle Passage—as the moment I was called to be a folklorist. If Daufuskie Island was my calling into the workways of Zora Neale Hurston and Anna Julia Cooper, then it is also true that this calling received sustenance at my maternal grandmother’s kitchen table back in Columbia, South Carolina. Anne Grace Richardson Caution served family lore like grits and communion, a curative to the symbols of white supremacy that marked the capitol grounds we’d walk to, including the battle flag that flew forebodingly and mockingly over my cousins’ heads and my own. Grandma’s table was a Black “oasis space” where she spoke of freedom and uplift, brilliance and wonder. As the wife of a career drill sergeant, she found herself, her children, and her grandchildren in South Carolina, but North Carolina was her birthplace and ancestral home. It is also now my chosen home and the birthplace of my child, Eden.

After settling in North Carolina as a new graduate student in folklore, I restlessly and ravenously began seeking the scattered bits of earth that held our familial memories. I traveled to the small plot of land where Grandma first walked. I poured libation at the formerly all-Black asylum for the so-called “insane” (Cherry Hospital) where, according to census records, a four-times great aunt, Henrietta, spent most of her life, along with fellow inmates Bessie, Winnie, and Cinda. I sought and seek out the old schoolhouses, the flat and rolling landscapes, the formally segregated barbecue spots, the city blocks, the battlefields, the planters’ homes, the wattle and daub dwellings, the formerly all-Black park (with carousel), the Jim Crow–era libraries, and the praise houses that served as backdrop and proving ground for our roots. Recently and retrospectively, I have been realizing that these formative moments of identity and seeking, of Blackness, southernness, womanhood, and the career they have inspired, have been as much about land and place as anything else.1

Every story my grandmother shared was a map and a monument. Well after her death, I still seek the materiality of her kitchen table narratives, retracing her words with my feet. As her matriarchal ethos has been my guiding light, it makes sense that, working with many colleagues, I have invested in mapping, marking, and commemorating the lifeways of Black people and particularly Black women. Beyond the stewardship of North Carolina’s historic sites, which involves marking hidden narratives and collaboratively creating portals of access, this work also includes ethnographic, archival, and in situ (architectural, landscape, and experiential) research related to the creation of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. And it includes giving voice to African American women and Civil War memory, conceptual contributions to the development of the African American Music Trails of Eastern North Carolina, and the collaborative efforts to commemoratively mark Pauli Murray’s childhood home, Anna Julia Cooper’s burial site, and Nina Simone’s birthplace. Digging deeper, the work has led me to proclaim settlements such as the Civil War–era Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony, the Trent River Settlement (James City), and Freedom Hill (Princeville) to be “Emancipation Communities,” while declaring the 326 North Carolina businesses featured in the Green Book (or The Negro Travelers’ Green Book) to be “oasis spaces,” in the same spirit of the Black Wall Streets of Tulsa and Durham. “Freedom Roads” was the name I gave to the waterways and landscapes that held and released the feet of enslaved freedom seekers called “runaway slaves” or “fugitives.” Carolina Blackness and the memories and lives of Black women are the threads stringing these cultural-spatial pearls.2

Womanist Cartography

When seeking new language for this work, I am inspired to offer up a concept I call “womanist cartography.” Alice Walker (Eatonton, Georgia) birthed the original definition of “womanist,” which can be found in full in the pages of In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens; here is an excerpt:

womanist

- 1. FROM WOMANISH. (Opp. of “girlish,” i.e., frivolous, irresponsible, not serious.) A black feminist or feminist of color. From the black folk expression of mothers to female children, “You acting womanish,” i.e., like a woman. Usually referring to outrageous, audacious, courageous or willful behavior. Wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered “good” for one.

Womanist cartography recenters Black women and femmes by rendering our narratives visible, audible, legible, and autonomous. The goal of this approach is to renegotiate Black femme presences in the American South.3

If cartography is the art of creating maps, of revealing the imagined borders and renaming practices by those arrogant enough to claim dominion over water and land, counter-cartographies and restorative cartographies are powerful tools for centering the marginalized and for repairing the fissures between one’s ancestral landscapes and ancestral memories. Particularly in the face of traumatic histories—histories of bondage, oppression, and generational poverty—restorative mapping can act as a transformative balm for those who feel wounded by memories of the land. Those not in this lineage, too, are offered the opportunity to recalibrate toward a more expansive awareness of place, in general, and the memories of the South’s geographies, specifically. Restorative and counter-cartographies are not just for healing the wounds of memory. These methods can illuminate the joyful and the spectacular, as well as daily acts of common humanity.4

Womanist cartography recenters Black women and femmes by rendering our narratives visible, audible, legible, and autonomous.

Mapmaking is not new to Black women. Louise E. Jefferson was a Black woman cartographer, designer, photographer, and African Diaspora multimedia documentary artist. Her papers include correspondence with one of her dearest friends, Black activist and priest St. Pauli Murray. I am perpetually ravenous for portals into Murray’s life and mind, but it was Jefferson’s maps that drew me to her. Of particular relevance to womanist cartography is Jefferson’s 1946 map entitled “Americans of Negro Lineage.” Here, she renders visible Black minds, Black labor, Black institutions, Black artistry, Black education, Black business, and Black lives. She roots them, places them in space, creating a testament, a transportable constellation of monuments. She declares, We were here.

We were here.

Paper and screen are not enough to hold these stories. The maps must be two-dimensional, yes, but they must also be performative, aural, visceral. They must reveal the nuances and majestic intimacies of daily lives while guarding against the specters of colonial voyeurism and appropriation. When we cannot listen to the voices of the living, the voices of the dead rise up to meet us in deeds, Black newspapers, census records, old cassettes, and photos that drop from cherished hiding places—we bring in the artists, the poets, the painters, the benders of light and sound. I envision women walking ancestral lands in pilgrimage, dancers on the battlegrounds, horns in revelry over streams that carried those running from bondage, T-shirts announcing their names, billboards shouting their legacies, more memorials, more monuments, more markers.

Afro-Carolina

A womanist cartography of Afro-Carolina begins with revisiting Afro-Carolina narratives across the land.

Virginia “Ginnie” Graves Williams, Caswell County, North Carolina

As a child, I was spoiled to my Grand-daddy. He used to call me “Baby.” I’m the baby. That was my name. I never heard him say “Virginia.” It was always, “the Baby.”

What he did was, he planted a whole field of popcorn for me, because we used to run through the corn. He used to get mad at us, damaging his corn. So he said, “I’m planting this for you.” We popped that corn. He showed us how. We had a tobacco barn. I would go up there, when they were curing tobacco at night, and they had this little pot thing that you could put the popcorn in, with a long handle. He would put it in the fire outside. He had a bench out there and he would stay up all night. He would pop popcorn and roast sweet potatoes and bake the apples in the ashes. Anyway, that’s the land that they swindled out of him when he was in his eighties. They came by when my mother wasn’t home to get him to sell his land for road frontage, because they didn’t want to sell theirs.

The “they” Virginia speaks of is the same family that her mother used to work for.5

Virginia’s mother’s name was Ruby Apple. Ruby Apple.

Ruby Apple was born at home on April 14, 1922, in Caswell County. She had a midwife. Ruby’s mother died young. Ruby owned one dress. She washed it and dried it by the fire and pressed it with an iron daily. As a little girl, worn down by teasing children who had realized Ruby wore the same dress every day, Ruby stopped going to school and began working in a white family’s home in Caswell County. She started by making bread. Too small to reach the counter, she was placed on a stool.

Her daughter, Virginia, works with schoolgirls and other community members at a recreation center. She coaches cheerleaders. Some of them are the same age her mother was when she began making bread in a white family’s home. The family land still holds this woman, child of Ruby Apple. Of the land that once held the field of popcorn, she says, “I want it back. I want all of it back.”

Brown girls who lived on this land would have swept yards, midwifed babies, cooked cornmeal on hearths, mended cotton dresses, sought out rabbit tobacco for a chest cold, tucked a cowrie shell in a wall, danced with a lover, tended the wheat and the tobacco later on, made soap from lye and ash and lard, made love, sung out to the air about home and freedom and dreams. They had names like Ruby, Ella, and Patsy/Piety.

Patsy/Piety, Halifax, North Carolina

$100 REWARD.

RUN AWAY, or was stolen from the subscriber on the night of the eighth instant a bright mulatto woman (slave) and her child, a girl of about four years old. This woman ran away from the subscriber, executor of John Hunt, dec’d [deceased], in the summer of 1808, and passed as a free woman by the name of Patsy Young, until about the first of June last, when she was apprehended as a runaway. On the 6th of the same month I obtained possession of her in the town of Halifax; since which time, by an order of Franklin county court, she and her child Eliza have been sold, when the subscriber became the purchaser. She spent the greater part of the time she was run away (say about sixteen years,) in the neighborhood of and in the town of Halifax; one or two summers at Rock Landing, where I am informed she cooked for the hands employed on the Canal. She has also spent some of her time in Plymouth, her occupation while there not known. At the above places she has many acquaintances. She is a tall spare woman, thin face and lips, long sharp nose, and fore-teeth somewhat decayed. She is an excellent seamstress, can make ladies and gentlemens [sic] dresses, is a good cook and weaver, and I am informed is a good cake-baker and beer-brewer, &c. by which occupations she principally gained her living. Some time during last summer she married a free man of colour named Ariel Johnson, who had been living in and about Plymouth, and followed boating on the Roanoke. Since his marriage, he leased a farm of Mr. James Cotton of Scotland-Neck, Halifax county, where he was living together with this woman, at the time she was taken up as a runaway slave in June last. I have but little doubt, that Johnson has contrived to seduce or steal her and child out of my possession, and will attempt to get them out of the State and pass as free persons. Should this be the case, I will give sixty-five dollars for his detection and conviction before the proper tribunal, in any part of this State. I will give for the apprehension of the woman and child, on their delivery to me, or so secured in jail or otherwise that I get them, thirty-five dollars; or, I will give twenty-five dollars for the woman alone, and ten dollars for the child alone. The proper name of the woman is PIETY, but she will no doubt change it as she did before.

I forwarn [sic] all owners of boats, captains and owners of vessels from taking on board their vessels, or carrying away this woman and her child Eliza, under the penalty of the law.

This ad appeared in the August 20, 1824 edition of the Raleigh Register and North Carolina Weekly Advertiser.6

Ella Baker, Littleton, North Carolina

[Littleton’s] name is very indicative of the size of the place.

There were a number of people who sharecropped and rented, but there were also in certain pockets . . . where my mother grew up and where my grandfather . . . had bargained or whatever else for a large tract of the old slave plantation which was broken up into plots of forty and fifty acres. And his relatives settled on it. This was to a large extent, by comparison, an independent community; they were independent farmers. But they also went in for the practice of [cooperation]—Helping each other. When I came along, for instance, I don’t think there was but one threshing machine for threshing the wheat. And so today they might be on Grandpa’s place, and all the people who had wheat who needed the thresher would be there, or at least some from those families . . . This section where we lived . . . the Blacks, our neighbors, each had their own place. Next to us was the Reverend Mr. Hawkins, who, in addition to being a minister, was a bricklayer. And men were artisans like brick [plasterers] and so forth. And somebody else was a carpenter. So you had at that time an intermix-ture. All of the heads of the families and their wives who lived in the section we called East End were at least literate. They had been to school somewhere, and many of them had been to what might have been considered college or an academy, because some of them had graduated from schools that are now like Shaw University. Shaw was one of the earlier schools in North Carolina established for Blacks. So you had a high degree of literacy and effectiveness in terms of public relations: speechmaking, leadership qualities and the like.7

Certainly the Carolina soil must recall the feet of Ruby Apple and her daughter Virginia Graves Williams, Patsy/Piety and her daughter Eliza, and Ella Baker, along with sculptor Selma Burke (Mooresville), visionary painter Minnie Evans (Pender County), comic genius Loretta Mary Aiken, also known as Moms Mabley (Brevard), Roberta Flack (Black Mountain), Shirley Caesar (Durham), Nina Simone (Tryon), Harriet Jacobs (Edenton), Pauli Murray (Durham), Charlotte Hawkins Brown (Henderson and Sedalia), and Anna Julia Haywood Cooper (Raleigh).

These lives weave together in ways that destroy the myth of the faceless southern Black woman, object of labor or doll-like declaration of chaste ladyhood. I can see, emerging, through these women’s voices, a new map, one that includes Virginia Graves Williams’s popcorn field, along with the lands that knew the untold labors of her mother, Ruby Apple. This new map includes the self-determined, autonomous journeys and freedom flights of the shape-shifting Patsy/Piety. The Roanoke River was her witness, so too were the towns of Plymouth and Halifax and the canal at Rock Landing. This map includes Nina Simone’s Tryon, Pauli Murray’s Durham, and Ella Baker’s Littleton, where Baker saw the rural rise of Black power and uplift, despite the trope of the relentlessly subjugated “Southern Negro.” This new map is womanist cartography.

We Ask More Questions

For the particular experiences and lived dreams, uprisings, and survivals of all Black southern women, how do we reveal the hidden markers of their lives on the land? What are the appropriate monuments? How do we remember—and re-member? How do we populate this map and find our way back to our mothers’ gardens time and time again? Where are the maps that trace the trails to our ancestral Black mothers, their horrors and hallelujahs?

We ask more questions.

Who was the woman Julian Carr “horse-whipped . . . until her skirts hung in shreds” after hiding in the buildings of the University of North Carolina, supposedly guarded by Union troops?8

Who washed the bodies and packed the satchels for the souls caught up and run out of Wilmington in 1898?9

Who twirled in crinolines in tobacco warehouses to Maceo Parker’s horn? Who grinded a mean and sensual “dog” in juke joints and at homecoming dances, fueled by corn liquor and love? Who sat dignified and festooned in pastels at the Church of God in Christ (cogic) “Pink Tea”?10

Who hosted the girls’ dormitory strategy sessions for freedom-making in January 1960 in Greensboro?11

What are our ancestral mothers’ names?

What did they call their journeying lands? Perhaps Texana.12

What did the soil look like, smell like, where they laid their heads? What are the names of the soils that held and hold our mothers?13

What were the ecosystems that witnessed their fallings and uprisings?

What was the birdsong that sang them to sleep and woke them up at dawn? Where is the compendium of our ancestral avian witnesses?

Where are the elevation maps of our mothers’ dreams?

Where is the GIS map that will lead me to the janitors’ closet where warm gingerbread was left for a weeping brown girl, sent by her people to integrate a university? Who were the groundskeepers and housekeepers and cafeteria cooks, also brown, who whispered the weather forecast of her heart, as her feet took her into classrooms cloudy and thunderous in white supremacy?14

How do we populate this map and find our way back to our mothers’ gardens time and time again? Where are the maps that trace the trails to our ancestral Black mothers, their horrors and hallelujahs?

What were the lullabies sung in their nursing ears?

What made them laugh?

Who were their loves?

These Black women have been watchers, birth-givers, and fuel, like pine sap–filled fatwood for this enterprise called “the South,” called Carolina. What are their names?

We know Lydia’s name. Lydia, rented by John Mann of Edenton for her enslaved labor, like one today would rent an apartment, a vehicle, a carpet cleaner from a grocery store. Beaten, shot, and used as fodder in the infamous 1829 North Carolina supreme court case State v. Mann, for which Justice Thomas Ruffin wrote in his opinion, “The power of the master must be absolute, to render the submission of the slave perfect,” no matter how cruelly the power was expressed, even to the point of deadly force. What more can we know of Lydia? Where were her people from? Where was she running when she was shot?15

“Home” is not a strong enough word to describe the relationship between the Black daughters of the South and her lands of origin. What are the words? Intrinsic, coexistent, paradoxically intimate, destructive, nutritive, reflective? The red and black and sandy tan of Carolina soils mirror her Black daughters in that we too are a spectrum from cream to midnight. We too have been plowed without consent into terrifying production. We too have sunk and risen above waters. We too have fed each other with our own loss. The land carries the bones of our babies and the bones of our own bodies carry her offerings. Many people who called this place home could sing such a song. But the voices of the South, by Black women of the South, are distinctive, as Anna Julia Cooper knew when she wrote her 1892 collection of wisdom and reflections. These foremothers held a bird’seye view of the South, witnessed from their hearths and dress folds, through their mortars and pestles and gleaning lands, and by their wombs.

This womanist cartography, this counternarrative that unearths what the land subsumed, calls and compels a leaning in, a listening to, a beckoning closer, to witness what the land has witnessed. We heal, we expand the table of memory, we surface the obscene, the taboo, the commonplace. We recalibrate our relationship to the marginalized and the mundane. Couching the act of revisiting cartographies through the lens of Black womanhood calls for new language: the language of listening to the land.

When we encounter an impression in the brickwork at Stagville in a posture of wonder, a fingerprint transforms from mark to monument. The clay knows the hand. The land knows the feet. The souls know the land. And what is this land, Afro-Carolina, without the souls of Black women?

This essay first appeared in the Art & Vision Issue (vol. 26, no. 3: Summer 2020).

MICHELLE LANIER is a folklorist, filmmaker, and museum professional. In 2018, she became the first African American director of North Carolina’s state historic sites. She has served as a faculty member at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University for two decades. Michelle is the proud mother of Eden.

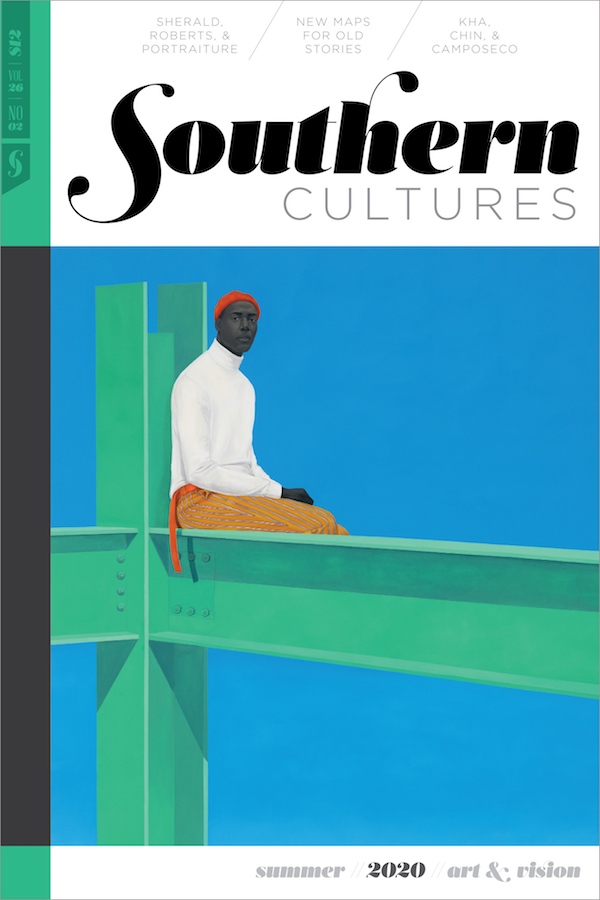

ALLISON JANAE HAMILTON (b. 1984) is a multidisciplinary artist working in sculpture, installation, photography, and video. In her work, Hamilton fuses land-centered folklore and personal family narratives into haunting yet epic mythologies that address the social and political concerns of today’s changing southern terrain, including land loss, environmental justice, climate change, and sustainability. The artist’s commitment to the land is driven by her own migrations, from Kentucky, where she was born, to Florida, where she grew up, to rural Tennessee, the location of her maternal family’s homestead, and to New York, where she currently lives.

Header image: Floridawater II, 2019. Archival pigment print, 24 × 36 in. Courtesy of the artist and the Marianne Boesky Gallery. © Allison Janae Hamilton.NOTES

- US Census Bureau, Population Schedule (1920, 1930, 1940), Ancestry, accessed November 20, 2019, www.ancestry.com.

- The collaborative nature of this place-making has allowed me to work with many colleagues, some of whom are in leadership roles with cultural preservation initiatives, including Valerie Ann Johnson, Carly Jones, and especially Angela M. Thorpe, director of the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission.

- Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983), xi.

- In my mind, counter and restorative cartographies are ways of knowing deeply connected to womanist cartography. We can consider countering work to be committed to revealing the untold stories of a landscape. Restorative work has to do with healing, empowerment, and engendering a sense of connection or reconnection to place.

- Virginia “Ginnie” Graves Williams, in an interview with the author, March 20, 2019. I had the opportunity to meet Virginia in 2018 in Wilmington, North Carolina. She was participating in a gathering of women in parks and recreational professions. As a featured speaker, I asked each woman to imagine bringing another woman into the space who had helped them advance either personally or professionally. Afterward, Virginia approached me and shared that she had “brought” her mother Ruby Apple into the gathering. Hearing the distinctive name, and a little of Ruby Apple’s story, a year later I recorded an interview with Virginia.

- Nat. Hunt., “$100 Reward,” Raleigh Register and North Carolina Weekly Advertiser, August 20, 1824, http://libcdm1.uncg.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/RAS/id/163/rec/1. I first learned of Patsy/Piety from the groundbreaking research of Dr. Freddie L. Parker, professor emeritus of history at North Carolina Central University. The North Carolina Runaway Slave Advertisements Project has made this and other advertisements, for freedom-seeking, enslaved people, accessible via a partnership between the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and North Carolina A&T State University.

- Ella Baker, interview by Eugene P. Walker, September 4, 1974, interview G-0007, Southern Oral History Program Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- “Unveiling of Confederate Monument at University. June 2, 1913,” folder 26, scans 104–105, Julian Shakespeare Carr Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, accessed March 29, 2020, https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/00141/#folder_26#1.

- While there continues to be a significant disparity between the historical record and communal memory around the Wilmington Massacre of 1898, a number of secondary sources offer illuminating analyses. Of particular note is Glenda E. Gilmore’s “Murder, Memory, and the Flight of the Incubus” and H. Leon Prather Sr.’s “We Have Taken a City: A Centennial Essay.” Both appear in David S. Cecelski and Timothy B. Tyson’s centennial commemorative text Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 73–93, 15–41.

- Beverly Patterson et al., “Schooled in Jazz and Funk: Kinston Area,” in African American Music Trails of Eastern North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 1–45; Michelle Lanier, “The Land Still Sings: An Epilogue,” in African American Music Trails of Eastern North Carolina, ed. Beverly Patterson et al. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 182. While exploring the personal archives of Dr. Goldie Wells, a civic leader and educator in Greensboro, North Carolina, and nationally recognized figure in the Church of God in Christ (COGIC) community, I learned of the annual COGIC “Pink Tea.” The tea focuses on fellowship and the attire and décor are indeed pink.

- Linda Beatrice Brown, Belles of Liberty: Gender, Bennett College, and the Civil Rights Movement in Greensboro, North Carolina (Greensboro, NC: Women and Wisdom Foundation, 2013).

- Texana is a historically Black and unincorporated township named for a Black girl-child born, ironically, not in Texas, but in the far reaches of North Carolina’s Affrilachia.

- According to the Natural Resources Conservation Service and the USDA, the most common soil type in North Carolina is comprised of the worn-down rock defined by intense heat (igneous), or intense heat and pressure (metamorphic), or sparkling feldspar (felsic, which glitters in much the same way as the speaker in a Pauli Murray verse: “I have been cast aside, but I sparkle in the darkness”; see Pauli Murray, “Prophecy,” Pauli Murray Project, Duke Human Rights Center at the Franklin Humanities Institute, accessed March 31, 2020, https://paulimurrayproject.org/pauli-murray/poetry-by-pauli-murray/). This blend of Piedmont soil is called “Cecil,” so named for a county in Maryland where it was first identified in 1899; see the USDA’s “Established Cecil Series,” accessed April 1, 2020, https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/C/CECIL.html; and the “State Soils” resource created by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, accessed April 1, 2020, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detailfull/soils/edu/?cid=STELPRDB1236841. Then there are also the Carolina sandhills and the wetlands.

- Early in my career as a public historian, I met colleagues at historically white universities who worked in areas of diversity, inclusion, and African American culture. This effort led me to East Carolina University (ECU), where I learned of Laura Marie Leary Elliott, the first full-time African American student to attend ECU in 1963. During my visit to the campus I learned that the Black cafeteria workers, custodians, and groundskeepers kept watch over Laura, sometimes leaving her a token of care and solidarity, be it warm gingerbread or a cold soda in a broom closet. I am still working to learn more about this narrative, a task challenged by the death of Laura Marie Leary Elliott in 2013.

- State v. Mann, 13 N.C. 263 (1829).