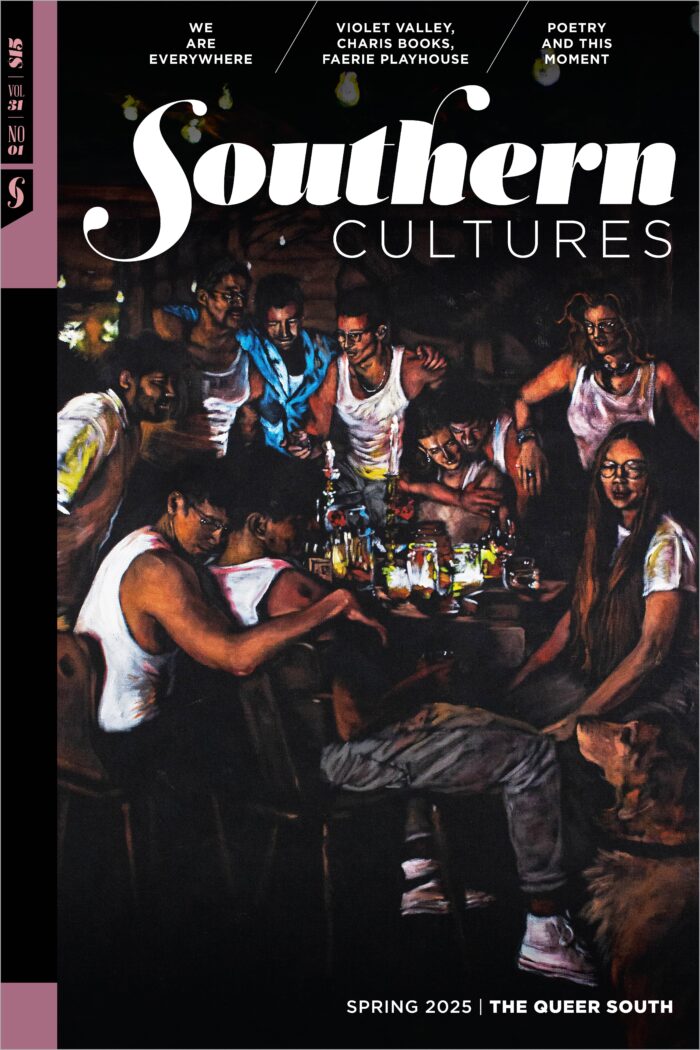

One evening in March 2024, I attended a cabaret fundraiser presented by the Common Woman Chorus, a Durham, North Carolina LBGTQ+ choir, and hosted by local drag queen Stormie Daie. Dressed in fancy sequined gowns or T-shirts and jeans, members of the choir sang everything from the Righteous Brothers’ “Unchained Melody” to Saturday Night Live’s “Tampon Farm,” and capped the evening with Cass Elliot’s “Make Your Own Kind of Music.” The choir defines itself as “a treble chorus made up of woman-identifying, gender-nonconforming, and transgender individuals” and “an LBGTQ+ centered space and a place for queer joy,” while Stormie Daie bills herself as the “Thunderous Black Enby Queen of Durham, NC.” During the performance, Daie introduced one of the performers as asexual and explained, “We value diversity here.”1

Until then, I hadn’t been under the impression that the lesbian, trans, and genderqueer choir with its nonbinary Black drag queen MC didn’t value diversity. As someone who is ace, or asexual, I wasn’t sure whether I should feel included in the evening or not. I remember glancing at my friends to see if anyone else was reacting to this statement, which was a departure from Daie’s otherwise humorous approach. Part of me was happy to be explicitly included in the event, but I also felt like I was in a sudden spotlight. By calling it out, Daie highlighted asexuality’s usual invisibility, and made its acceptance an unusual act, rather than just another part of a broad queer community.

Asexuality is generally defined as lack of feeling sexual attraction. Discussions of asexuality often reference the Asexual Visibility and Education Network, a website founded in 2001, but over the past twenty years, many online spaces and social media sites have increased visibility and understanding of the concept. The best definitions resist essentialism and frame it as a spectrum, with some people who identify as ace experiencing little to no sexual attraction and others experiencing varying levels. Online ace communities have developed microlabels like grey ace for those who occasionally experience sexual attraction and demisexual for those who experience sexual attraction only after forming a close emotional bond. While these labels can impose their own limitations, they help express how asexuality can be fluid and difficult to articulate. Asexuality is often discussed alongside aromanticism, which is having little or no romantic attraction or romantic feelings toward others. Some people identify as both ace and aromantic, while others identify as one or the other. Because it is defined by a lack of sexual desire or attraction rather than by the direction of that desire and attraction, asexuality is known as “the invisible orientation.”2

I do not remember exactly when I first encountered the word asexual, but it was likely in 2004, during my senior year at Vanderbilt University, in Beth Boyd’s Gender and Sexuality in the South course. I didn’t immediately latch onto the term; I remember considering it and rejecting it for myself in favor of thinking, “I just haven’t met the right person yet.” This refrain is common to many ace folks, who hear it from friends, family, and society. We internalize it until we begin to question its assumption of compulsory sexuality—as I did later.

I didn’t begin to think of myself as ace until a decade later, in 2014, when I was underemployed, depressed, and spending a lot of time on Tumblr. I followed many queer accounts, and my feed was filled with ace people claiming that identity for themselves. I bookmarked so many posts but could not bring myself to read them. It took me a long time to admit to myself that I felt what all these people, many of whom were much younger than me, were articulating. They described bewilderment at others’ descriptions of sexual attraction, found themselves unwilling to enter sexual or romantic relationships to fit in or satisfy someone else’s desires, and sought a different space for themselves and their experiences. How could they know? I asked myself. They’re so young, they haven’t done much, how could they know?

What I really meant was, how could I not know? And how do I live going forward with this knowledge, in a world of compulsory sexuality and nuclear family units that can hardly imagine anything beyond a two-person romantic and sexual partnership? Growing up in Alabama, I barely knew anyone whose parents were divorced, much less anyone who was openly gay or lesbian. I didn’t even know alternative family structures existed outside of science fiction novels. I’ve spent most of my life in the southeastern United States, a region not necessarily known for its openness to queerness—but still a home for many LGBTQ+ people. In college and grad school in Tennessee and Mississippi, respectively, I did meet queer people, who found community in more accepting spaces like theater departments, philosophy and fine arts–focused dorms, humanities graduate programs, drag shows, and queer-friendly, if not explicitly queer, bars. Some were openly out, while others were quieter about their identities. All had to negotiate their own visibility on campuses with newspaper op-eds about the sin of homosexuality and regular homophobic graffiti in dorm elevators. The campuses might be liberal enough for productions of The Laramie Project but still homophobic enough for actors to be harassed and cat-called during performances.

In Men Like That: A Southern Queer History, scholar John Howard explores the region’s tendency toward what he terms a “quiet accommodation” of homosexuality. Whether you are gay or lesbian matters less, he argues, than whether you are known to a community. Rural and small-town southerners during the mid-twentieth century allowed space for a great deal of queer behavior so long as it was not “out and proud” and the social order was not challenged. On southern college campuses in the early 2000s, queerness was accommodated within certain clubs or departments but was met with derision and even hostility when openly displayed or critical of heteronormativity.3

But queer people in the South have never been content with quiet accommodation and have long fought for, and continue to fight for, visibility and space. Larger cities like Atlanta, Nashville, and Richmond have a long—though tenuous—history of gay bars and Pride parades, and rural and small-town Mississippi and Alabama saw a wave of Pride parades emerge after the US Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges. Though LGBTQ+ resources remain underfunded in the South, there are a growing number of LGBTQ+ centers, PFLAGgroups, and queer student organizations across the region. I have been lucky to march in some of those parades and support some of those organizations. These are important spaces for queer communities, as the South, like the rest of the country, has also seen a flood of antiqueer legislation since Obergefell. Even as queer people and communities are increasingly visible in the South, within those spaces, few if any openly identify as asexual, and even organizations that include the “A” in their acronyms focus on other parts of the community. The broader culture doesn’t even quietly accommodate asexuality, since few are aware that it exists.

Because asexuality involves a lack of feeling, describing it can feel like trying to prove a negative, and this difference from other constructions of sexuality makes asexuality harder to see. I could spend the rest of my life telling people, “I’m just not dating anyone right now,” without ever having to name myself as ace. And many people who don’t experience sexual attraction may never put a name to that lack of feeling, encounter the concept, or identify with the idea of asexuality.

The modern tendency to put everything into an identity category further complicates an understanding of asexuality. Howard makes a distinction that is helpful: he differentiates the phrase “men like that” from “men who like that”; “men like that” assumes that male-male desire is a constitutive identity, whereas “men who like that” describes those with particular desires or behaviors. “Queer is a useful rubric” here, Howard argues, because it opens up interpretive possibilities not otherwise available when relying on strict identity categories. Asexuality scholar Ela Przybylo admits in her introduction to Asexual Erotics that her work is “written from a place that is invested in asexual visibility and yet leaves me sometimes fraught at writing a book that is less about an identity and more about critiquing sexually overdetermined modes of relating.” Framing asexuality as an identity can imply that it is relevant only to the few who are ace.4

I am sometimes uncomfortable with a label that could, in a different historical moment, simply be understood as a set of desires, tendencies, or preferences, rather than as a constitutive identity. I was finally able to claim asexuality for myself when I decided that I could still leave a window open to the potential of another experience: even if I did magically feel sexual attraction one day, that would not erase the many years I spent not experiencing it. Like Howard’s inclusion of “men who like that” with “men like that,” embracing asexuality as not just an identity but also a challenge to compulsory sexuality can expand our understanding of queerness more broadly and help us envision new, and hopefully more liberatory, forms of relationality.

I find that my asexuality is often misunderstood in ways that have more to do with other peoples’ insecurities than anything about me or the category itself. People, as it turns out, are insecure about their sex lives. Whenever my asexuality comes up in conversation with one of my friends, she immediately starts talking about her sex life, specifically how many people she has had sex with—a number she is clearly uncomfortable with but returns to again and again. Another friend immediately reflects on the lack of sex in his own life. Both friends separately label their marriages “asexual,” which is a misunderstanding of the term and also an expression of their struggles with compulsory sexuality. Asexuality is not about sex itself; many ace people do choose to have sex for reasons other than feeling sexual attraction. Recognizing asexuality’s lack of desire or attraction can help normalize the fluidity of sexual attraction or desire and reveal cultural assumptions about sexual expectations.

A friend recently texted to ask if I would be interested in “getting an ace partner who lived in the apartment next door but was still intimately close as far as companionship goes.” She immediately followed up by texting, “I meant to delete that.” I’m glad she hit Send. Accidental or not, her text sat with me for several days. The moments that highlight my asexuality the most are like this: feeling uncomfortable with a comment or assumption someone has made but being unsure why. Accepting my asexuality has thankfully meant that I no longer assume something is wrong with me but with the comment or assumption. My friend’s text made very specific assumptions about what I might want, framing my options in terms of a normative two-person partnership.

I don’t know if I want an ace partner who lives next door but is still a very close friend. What I do know is that this is a failure to imagine any kind of kinship that extends beyond the hetero- or homonormative. Our social norms construct an idealized lifestyle through the model of a two-person romantic and sexual relationship that cares for children. Sophie Lewis’s family abolition work calls this “a socially organized scarcity of care” or, in a more memorable formulation, a “disciplinary, scarcity-based trauma machine.” Mental and emotional health, companionship, housing, healthcare, access to education, economic stability, and so much more are channeled through a family unit anchored by a two-person partnership. I want to be free from the expectation that I should want a partner, ace or otherwise. I want to belong to a community—a queer community—that imagines relationships and care differently.5

I am fortunate that I never had to have a sexual or romantic relationship with someone to obtain access to housing or food or education or self-worth. I have known many friends over the years who have stayed in relationships longer than they wanted because they could not afford rent on their own, or because they felt worthless without a partner, or because they thought their children needed a father, even an abusive one.

I am lucky to have parents who value education and who were willing and able to pay for it; I also could not have afforded to move for job opportunities without their help, nor could I have afforded initial payments for cars or cell phones or computers on my own. My father helped me start my checking, credit card, and retirement accounts. I have some self-sufficiency because my parents, through their own heteronormative two-person marriage, have been my support system. Without that structure, and their dual incomes, I would have had far fewer opportunities.

My experience with asexuality is inextricable from the effects of race, gender, and class I experienced growing up. My father served in the Alabama House of Representatives when I was a small child. He and my mother chose to belong to the Anniston Country Club, and they sent me to a private school that had its beginnings as a segregation academy. All of these spaces had very narrow conceptions of gender and sexuality, building on a long history of strictly policed relationships between men and women and between Black people and white people. In the predominantly white South that I grew up in, women were driven by images of perfectly blonde sorority girls, beauty queens, and southern belles in hoop skirts. Men were compelled to participate in a hypermasculine, often violent, culture of sports, guns, and violence. This system allocated power through a binary gender and sexual ideology and maintained hierarchies through racism and sexism and homophobia. The only future visions available to me involved marrying a white man and having children. My job would be less important and I would make less money than my husband. I would take on the bulk of child-care and housework, and my husband would be in charge. Other options might as well have not existed. While interracial or queer relationships were not as marked by violence as they had been during the Civil Rights Era and earlier periods, they were still understood to violate social norms, and few if any existed that I could see.

Even as an ace person, I benefit from some of these norms. Because sexual expectations and assumptions about men and people of color often assume hypersexuality, being understood as asexual is slightly more accessible to me as a white woman. Stereotypes about white women don’t assume hypersexuality, and “saving yourself ” for marriage is still encouraged in southern churches. But even those who are able to align with sociosexual norms are still harmed by them. The privileges of race and class don’t spare me from sexism, misogyny, and acephobia. The trauma that we experience trying to live up to strict norms makes imagining an alternative even more urgent for all of us.6

In Ending the Pursuit, artist and writer Michael Paramo uses the term azeness to describe “the experiences of ‘absence’ that are shared by asexual, aromantic, and agender people amidst the norms and expectations of cisheteropatriarchy.” Azeness, he says, can reveal the structures of settler colonialism by serving as a “conceptual reference point . . . to reflect on the myriad ways colonial (il)logics have trained us to engage in pursuits that, at their core, are detrimental to our well-being.” This decolonial worldview can make visible and counter the deeply rooted logics of racism, sexism, homophobia, and compulsory sexuality. Using azeness as a lens helps name the social and sexual constructs that harm us, and ending our pursuit of them opens possibilities and choices that can move us in a more liberatory direction. I don’t yet know what this might look like. I know that I don’t want to be cut off from the possibility of deeper relationships because I don’t, or can’t, participate in compulsory sexuality. I don’t want the only option for committed relationships to be reserved for a two-person sexual and romantic partnership. I don’t want to forever come second to those in my life because I’m not a spouse or a romantic partner. I want to belong to a community that embraces more options.7

In the introduction to Men Like That, Howard recalled his first visit to a gay bar in his home state of Mississippi. His reason for visiting the bar was “motivated less by an impulse to act on queer desire than by a need to witness a community organized around queer desire.” Like Howard, I attended the Common Woman Chorus show not because I was there to experience desire, but rather because I wanted to be in queer community, in a place where heteronormativity is not assumed or expected. My hope is that we can organize ourselves around a resistance not only to compulsory heterosexuality, but also to compulsory sexuality, and in doing so, open opportunities for the kinds of relationships and care that can be available to all people.8

So I ask you to consider: what would your life look like if you had never had any romantic or sexual relationships? What would it look like if you had never wanted one? What world would you want to build?

Ellie Campbell is a clinical associate professor of law and reference librarian at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research interests include critical legal research, law and speculative fiction, and the queer South. Her most recent publication is “Critical Legal Research, Artificial Intelligence, and Systemic Racism: Teaching with Jim Crow Text-Mining,” in Legal Reference Services Quarterly.

NOTES

- “About Us,” Common Woman Chorus, accessed June 10, 2024, https://www.commonwomanchorus.org/about-us; “Stormie Daie,” Stormie Daie website, accessed June 10, 2024, https://www.stormiedaie.com/.

- See, for example, Sherronda Brown, Refusing Compulsory Sexuality: A Black Asexual Lens on Our Sex-Obsessed Culture (North Atlantic Books, 2022), 2–3; Ela Przybylo, Asexual Erotics: Readings of Compulsory Sexuality (Ohio State Press, 2019), 2–3; Michael Paramo, Ending the Pursuit: Asexuality, Aromanticism, and Agender Identity (Unbound Books, 2024), 4–6; Kristina Gupta, “‘And Now I’m Just Different, but There’s Nothing Actually Wrong with Me’: Asexual Marginalization and Resistance,” Journal of Homosexuality 64, no. 8 (2017): 991–1013; Julia Sondra Decker, The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality (Skyhorse Publishing, 2014).

- John Howard, Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (University of Chicago Press, 1999), xvii, 142.

- Howard, Men Like That, 5, 6; Przybylo, Asexual Erotics, 3.

- Sophie Lewis, Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation (Verso Books, 2022) and “Mothering Against Motherhood: Doula Work, Xenohospitality and the Idea of the Momrade,” Haters Café, accessed June 10, 2024, https://haters.noblogs.org/files/2022/03/Mothering-Against-imposed.pdf, 5.

- See Paramo, Ending the Pursuit, 35, and, generally, Brown, Refusing Compulsory Sexuality.

- Paramo, Ending the Pursuit, 5, 187.

- Howard, Men Like That, xxii.