I am currently living in several places at once: in Stone Mountain, Georgia, on the homelands of the Muscogee Nation; in the United States; on Turtle Island, Abia Yala, or Mother Earth. As part of my commitment to the Muscogee (Creek) people who have stewarded this place longer than anyone else, I am learning a little bit of the Muscogee language, trying to make a positive contribution to the places where the language was created, so those places can hear the language that was born here. I am not good at it—I have no grammatical knowledge and am just starting to pick up on the sounds—but I am enjoying it. As a greeting, Muscogee people will say “estonko cukhayvtikv,” which translates to English as, “How are you?” or “Did you make it through the night ok?” or “Are you well?” or “Are you without problems?” The question hopes that the night, when it departed, left behind no troubles for you; that when you awoke in the morning, you inherited a well body and easy spirit.

I am not Muscogee. I am a member of the Lumbee tribe of North Carolina, and Stone Mountain is not my homeland. Before moving here, I imagined this town as a haven for Confederate sympathizers, given that the Confederate monument carved into the mountain is the largest in the world. The sculpture was begun in 1915 when the site was privately owned by a Ku Klux Klan member who deeded a portion of it to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The carving was only completed in 1972, after it became a publicly funded Georgia state park. The story of the monument represents the journey of anti-Black racism from an ostensibly private property concern to one embraced by elected officials—something that citizens of Georgia have been fighting ever since the story began.

But the story of the monument is not the story of the mountain, nor is it the whole story. Living here, I can see why creating the work took so long. Stone Mountain is a majority Black and Brown community; in 2021, the Black population was estimated at 86 percent. Historically, the village of Stone Mountain included a Black town called Shermantown (yes, after William T., who famously burned Atlanta), home to Dekalb County’s first Black school, founded by formerly enslaved people. Music, comedy, and television artist Donald Glover grew up there and recalled the attempts to erase its Black history: “Confederate flags everywhere. I had friends who were white, whose parents were very sweet to me but were also like, ‘Don’t ever date him.’”1

In my own personal, brief experience of Atlanta (I moved here in July 2021), it seems like the legacy of Jim Crow is everywhere and nowhere. I rarely move in a space that does not contain a significant number of Black people, yet the marks of exclusion are present in formerly red-lined, now gentrified, neighborhoods. Atlanta’s international character is everywhere present in its food, music, and arts communities, as well as in acts of anti-Asian and anti-Black violence. Few people have any knowledge of the city’s Indigenous people, even as the veritable main street, Peachtree Street, is named for a Muscogee village called, in English, “Standing Peachtree.”

It’s profoundly strange to me that a group of people so deeply in the minority, such as white people in metro Atlanta, think that it’s ok to extinguish a Black or Indigenous story in favor of a Confederate one. A Native friend of mine hikes Stone Mountain regularly and reports that she rarely sees white hikers and recreational users. Personally, she has made a commitment to maintain that space for nonwhite people, resisting the story told by the monument. While I have not heard Muscogee people discuss it, I can only imagine that the mountain has been a location to gather since their origins in this place, which is to say, since time immemorial. In the short time since racists have tried to control the mountain’s story, the mountain, drawing on the people, has pushed back.

As a Lumbee, I have no connection to my ancestors’ Indigenous languages. Inheritance has become something else, and I play with how English words sound in my mouth and the ideas they communicate. “I stand to inherit,” I sometimes think. But then I ask, “Am I set for life, wealthy, without problems?” Or, “I will inherit nothing,” I say. Then again, I ask, “Am I destitute, forlorn, trapped in an endless struggle?” Either way, my Lumbee family has adopted capitalist habits, in that we usually think of an inheritance as property, as items that can be listed and counted, categorized by type, and assigned value. Capitalist valuation compares and ranks both the invaluable and unvaluable, as if one identity could be worth more than another, as if one lineage outweighs another, as if land is worth more than water is worth more than people, and so on.

We inherit things, items, property, but also names, traits, and qualities. And one of the truly bedeviling things about our sincere desire to reckon with our inheritances is the lack of direction we face when trying to decide what we must atone for. When what we inherit can’t be deeded or catalogued in a will or on a census or a tribal enrollment application, our ancestors provide no direction about what to do with those things that have stories we do not understand, or stories that communicate values we reject. We want a recipe to be passed down, but we receive only the ingredients, with no directions about how to use them, no instructions about the right choices to make. There is no recipe to follow for historical reckoning. Some of us spend our entire lives trying to find the instructions.

The law thinks of inheritance as individualized, but inheritance is also collective, which is to say that we have to take the good with the bad. Our ancestors unintentionally passed on things that create collateral damage. I feel this about my family. As proud as I am of them, of what I’ve inherited—an ear for music, a talent for baking, brown eyes—I also know that I’ve inherited things my ancestors didn’t intend to pass on: high blood pressure, a mean streak, an impatience that has been my undoing. Depending on where I am and when, these inherited traits might compromise me and the prospects for inclusion and belonging that I can experience. My daughter inherits these traits as well, which could put her at greater risk. A sad truth of the United States is that she, as a Native person, by virtue of her belonging in that community, must accept accountability for things she didn’t do. Unlike many of her white peers, who are primarily saddled with the good or bad consequences of their own choices, she faces obstacles that are shaped by stereotypes, myths, and assumptions she has no choice but to inherit—obstacles that are manufactured by labels, by race and her racialized body, by her minoritized status, by her intersectional identities as Indigenous and female. I am acutely aware of what I may inadvertently pass on to her, and so the stakes of this conversation are high.

Inheritance can provide stability that is both desirable and undesirable, and without an understanding of the tensions and compatibilities that show up in the differences, the ghosts of our inheritances can do some damage. The uneasy relationship between these senses of security and the accompanying hauntings can be partially settled by exploring the possibilities of American and African Indigeneities in the past and present. Standing Rock Sioux scholar Vine Deloria Jr. provides some insight about this tension in his recognition that hereditary governance provides a stability that the United States utterly lacks. To be sure, European settlers’ pursuit of a noble dream of democracy and positivist rationality has galvanized a global, shared struggle for equality, but it has also produced fragile social bonds. Of course it did when the pursuit of freedom and individual liberty went hand-in-hand with exploiting Indigenous people and lands across the globe, with genocidal acts that were justified by the idea of natural, inheritable inequality, and with the uplift, innovation, and progress of one race at the expense of others.2

It is no wonder, then, that an iconoclastic thinker such as Deloria would ask us to take seriously what most Americans reject: a hereditary system of governance that channels power to a central core, rather than outward to infinite numbers of loose ends. Hereditary governance, like that practiced by many Indigenous peoples on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, is not a far stretch from communal structures that do not leave the individual alone to fend for themselves. We may have individual freedoms in the United States, but when disaster strikes, we also have no one to turn to, unless we have been persistently critiquing the system of individualized freedom and developing (or sustaining) our own systems alongside of it.

The way we speak of history in these nominally free societies mimics the values they reinforce. “If we take a linear viewpoint of the world,” Deloria writes, “the sequence of spectacular events creates the impression that the world is going either up- or downhill. Events become noted more of their supportive or threatening aspects than for their reality, since they fall into line and do not themselves contain any means of interpretation.” In this kind of society, the American Revolution is a glorious moment of universal liberty, but the Reconstruction amendments are a threat to the integrity of the nation. This viewpoint enables seemingly rational public actors to argue that the Fourteenth Amendment and birthright citizenship must be repealed in the face of changing demographics brought by immigration. Such a move, while outrageous and unlikely, is a deep distraction from related and more substantive efforts to restrict individual liberties, such as reinstating the ban on abortion.3

With a linear viewpoint on the world, politics and policy are just a few of the aspects of leadership that prove capricious, unwieldy, jagged, and ultimately prevent the stated aim of democracy here on Turtle Island. Deloria addressed the impacts of these distractions on our decision-making: “When we are unable to absorb the events reported to us by the media, we begin to force interpretations of what the world really means on the basis of what we have been taught rather than what we have experienced.” What we have been taught is necessarily narrowed by the limitations of our teachers, whereas what we have experienced is itself a deep well of resources that are transmitted across generations. Traumas can be transmitted this way, but so can resilience and problem-solving. Scholars in the fields of social work, nursing, education, and the humanities are finding evidence that communities hang on to both.4

Presaging this research, Deloria poses an alternative, one which animates this Southern Cultures issue. He writes of “the tribal viewpoint” as a site of resilience. That viewpoint is not perfectly expressed in the form of tribal governments, which have themselves been subject to colonial subversion and which perpetuate many forms of inequality, but Deloria highlights it because it is a way of living that many Americans of every kind of origin have, in fact, embraced. A society that values shared responsibilities and protects them with the same fierceness it protects individual rights “simply absorbs what is reported to it and immediately integrates it into the experience of the group … The more that happens the better the tribe seems to function and the stronger it appears to get.” This process explains the persistence of Native people through the traumas that colonizers designed to eliminate us.5

Telling one’s own story is an assertion of identity, and unfortunately Indigenous, Black, and Black Indigenous people have come to expect obstacles that white scholars, artists, and writers do not have to face. Rarely are white Americans’ narratives stolen out from under them and appropriated beyond recognition. As Nikole Hannah-Jones details in the introduction to the 1619 Project edited volume, for example, the obstacles that scholars and writers of color face in telling their own stories come to be seen as a result of our supposed poor understanding or inadequate training rather than the burdens imposed by the institutions and systems that have marginalized us.

Rather than dither with those distractions, however, Black and Indigenous scholars, in particular, are forging ahead to demonstrate how what we inherit is, as contributor Kendra Taira Field considers, a matter of life and death. The misidentification of ancestors, or incomplete or misleading identification, not only creates identity conundrums, but it has very real consequences, down to the ideas about belonging and resilience that are the very source of functioning Indigenous societies. The forum of essays included in this issue from Black, Indigenous, and Black Indigenous scholars highlights these silences and misdirections and the enduring pain they cause, but also shows how to work through them. These essays address what we do in spite of colonialism and imperialism, and ask, what are the conversations Black and Indigenous people need to be having with one another? What does displacement do to our shared inheritances? What legacies do they create in our bodies and families, good and bad?

This forum helps us manage the conflicts we inherit. When we inherit something we are not proud of, we cannot merely disavow it—not if we want to see permanent change, and not if we want to see wounds healed. And if we see ourselves as ancestors—which we hope we are—it becomes impossible to repeat history, at least with a good conscience. We have a responsibility, not just a right, to make decisions that will be good for our descendants. Where history teaches us they will not be good, we have to rethink, retool, and collaborate to make sense of the right path forward.

This very issue of Southern Cultures is a reckoning, as it takes up, examines, and then takes apart the mythologized histories and cultures of our home region. In this issue, all of the authors, in some way, are reckoning with their inheritances—on various journeys “to find my way back home, to my original place,” as Esther Oganda Ohito writes in “My Inheritance.” The essays collected here call us to look deeper, to see episodes in the past as a series of possible instructions to follow. After all, we inherited some of the same ingredients—desires for liberty, for connection, for self-determination, desires for security and comfort. A desire to share, to partner, and pass on what we know. We inherited the flip side of human nature as well—the desires of lust, of greed, of power and control, and their instruments: exploitation and unchecked accumulation. A responsible, honest reckoning with our whole inheritance evokes positive and negative emotions. Such a reckoning forces us to confront ambiguity, uncertainty, and the attendant pressures they place on our communities. Lauren Frances Adams and Jason Patterson’s conversation describes what we do very well: “On one hand, there’s work that needs to be sat in and get mucky and take your time through, because it’s about undoing more than just the name of a school or a dorm (in the case of Cornelia Phillips Spencer at UNC).”

Between 2018 and 2020, while I served as director of the Center for the Study of the American South (CSAS) at UNC-Chapel Hill, I facilitated the project that Adams is describing—a collaboration between teams of artists and scholars (many people are both, as this conversation attests) to envision unc’s future without a Confederate monument. The staff at csas, especially of the Southern Oral History Program and Southern Cultures, felt that our convening would be inauthentic if we did not place our offices, the Love House and Hutchins Forum, at the center of this reckoning. We knew the history of the family who built the house and the woman, Cornelia Phillips Spencer, who lived there. But we needed to see this history and its traces, its ingredients, visibly in our space in order to experience their transformative potential.6

These authors also remind us of the role of place in reconstructing what the inheritance even is, and the daunting, haunting, work involved. The security that inherited property seemingly provides belies the ghosts that stick around through the objects of our lineal ancestors, such as the strip boats Zachary Faircloth describes. Ryan E. Emanuel and Karen Dial Bird’s essay demonstrates how ancestors stick around in a different way, shielding us from the burdens of extractive research and misinformation to ensure that, through it, we are made stronger, not weaker.

As part of Emory University’s efforts to build relationships with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation on whose land the campuses are built, I traveled to Oklahoma in the spring of 2022. In Oklahoma, I consistently found myself wondering if I was in the South or the West. We heard how embers from fires in traditional towns were brought from Georgia and Alabama across the River of Death (the Mississippi) and rekindled in Oklahoma. Further, Muscogee people brought to the West many of the traditions they innovated in the South, that white southerners have since appropriated as their own. Hospitality is just a start. Everywhere we went, we received gifts of food and objects to carry home, lessons in how to live respectfully, invitations to learn and be accountable.

During our visit, we had the privilege of eating a wild onion dinner made by a Muscogee chef, Carol Tiger. Wild onions are foraged in the late winter, and their locations are kept secret in part to ensure a continual yield across generations. Eating the toothsome and tender, sweet and sour greens, I was reminded that it is labor intensive, not just the foraging but the keeping of secrets. Just telling everybody is easier, but if we do, we make what should be protected exploitable. The dinner became a metaphor, in some ways, for the entire trip, and even more so for the journey I am on to relate to my places in a deeper way that has more integrity. What right do we have to know? Muscogee people bestowed gifts generously, but there is also an expectation of reciprocity. What right do we have to tell? We cannot say what Muscogee history is without Muscogee people alongside us. The danger is acute: portraying the past as a linear progression of events separates people from their places, and our history teaches us that in the separation, violence and oppression enter.

As I traveled in Oklahoma, I thought about Stone Mountain a great deal, less for its ancient significance to Muscogee people, which I have no right to know, and more for its power to overturn the meta-narratives about Black and Indigenous disappearance, invisibility, marginality, and death. So that we may have a life for our descendants.

This essay introduces the Inheritance Issue (vol. 28, no. 3: Fall 2022), guest edited by the author.

Malinda Mayor Lowery is a historian and documentary film producer who is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. In July 2021, she joined Emory University as the Cahoon Family Professor of American History, after spending twelve years at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and four years at Harvard University.

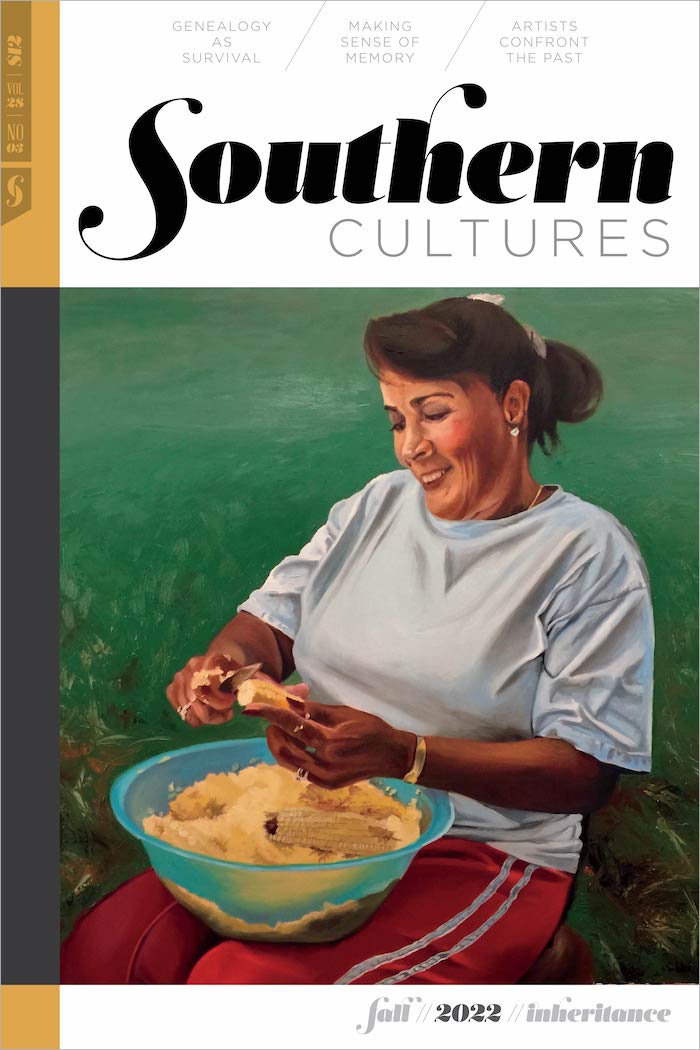

Header image: Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier, Dancing La Sola Sola, 2018. Acrylic on panel, 48 × 48 in.NOTES

- Bijan Stephen, “Donald Glover Has Always Been Ten Steps Ahead,” Esquire, February 7, 2018, https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/a15895714/donald-glover-atlanta-march-2018/; Benjamin Powers, “In the Shadow of Stone Mountain,” Smithsonian Magazine, May 4, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/shadow-stone-mountain-180968956/; United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: Stone Mountain City, Georgia,” accessed May 14, 2022, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/stonemountaincitygeorgia/PST045221.

- Robin D. G. Kelley, “The Rest of Us: Rethinking Settler and Native,” American Quarterly 69 (June 2017): 267–276.

- Vine Deloria Jr., We Talk, You Listen: New Tribes, New Turf (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 16; Jonathan Swan and Stef W. Kight, “Exclusive: Trump Targeting Birthright Citizenship with Executive Order,” Axios, October 18, 2018, https://www.axios.com/2018/10/30/trump-birthright-citizenship-executive-order.

- Deloria, We Talk, You Listen, 16. See the research of Jessica Lambert Ward, discussed in Hadley Chapman, “Carolina Collaborative for Resilience Offers Student Coaching Program,” Daily Tar Heel, March 27, 2022, https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2022/03/university-resilience-coach-program; Geeta N. Kapur, To Drink from the Well: The Struggle for Racial Equality at the Nation’s Oldest Public University(Durham, NC: Blair, 2021); and Cherry Beasley, Mary Ann Jacobs, and Ulrike Wiethaus, Upon Her Shoulders: Southeastern Native Women Share Their Stories of Justice, Spirit, and Community (Durham, NC: Blair, 2022).

- Deloria, We Talk, You Listen, 13.

- The results of the collaboration, including Adams’s work, are hosted at “Imagining UNC’s Future with Art: Reckoning with Silent Sam,” Center for the Study of the American South, accessed July 17, 2022, https://imaginingfuture.unc.edu.