“To address the climate crisis, you have to recognize how climate change is intersecting with other issues, such as poverty, racism, socioeconomic inequality, injustice, and more.” —Katharine Hayhoe

These lesson plans were developed through the “Portraits of Climate Change” initative—a collaboration between Southern Cultures, Carolina Public Humanities, and NC Community Colleges. They are designed to assist high school and college instructors interested in using Snapshot: Climate to empower their students to employ the arts and humanities and reflect on climate change in their own communities.

Are you an instructor interested in using Snapshot: Climate in the classroom but don’t have print copies? Please contact hello@www.southerncultures.org to request free copies or digital access.

Lesson Plan 1:

“Re-Storying” our Changing World

Overview:

This lesson helps students to explore what climate change looks like in their own community.

It hones in on the power of storytelling and of artistic expression in taking abstractions about climate change and driving home their real-world impact.

Essential Questions

- What does climate change look like in your community?

- How does your community’s experience fit into broader patterns throughout the South?

- How can art—especially photography and writing—convey truths about a scientific dilemma?

- Why is storytelling such a powerful tool in encouraging the fight against climate change?

Materials

Copies of Snapshot: Climate for each student—may be distributed ahead of time, or in class

Duration

60–90 minutes

Preparation

Students should have a basic understanding of climate change. If they have any background in thinking about environmental justice, it will also prime them to think about why some communities and regions may be more vulnerable to the immediate impact of climate change than others—and why some of those communities may also be most active in pushing for innovative strategies of building climate resilience.

Instructors who provide copies of Snapshot: Climate in advance to students may choose to assign one of the following readings ahead of time:

- For a general introduction to climate change, from a scientist: “Climate Change is an Everything Issue,” an interview with Katherine Hayhoe (130–141)

- For a policy-based approach, with a particular focus on environmental racism: “Before the Streetlights Come Back On,” by Heather McTeer Toney (142–156)

- For a more literary/creative example of the themes of this issue: “The Inner Banks” by Megan Mayhew Bergman (160–166)

I. Climate Change & Home

[10–15 minutes]

This warm-up activity provides students with a chance to reflect on differences between how various communities feel the impact of climate change, as well as on potential generational differences in attitudes towards climate change.

- Ask your students to brainstorm words they associate with “home.” Write them on the board.

- Then add the words “climate change.” When they put this word together with “home,” what changes for students? What new words would they now put up on the board? Students may add words about specific climate impacts on their area—e.g. flooding, fires, drought, no snow—or they may use emotional language—e.g. scary, change, uncertainty, etc. All of these are helpful!

- Ask students whether they think that a different group of students from their own school would come up with a similar set of words. What about a room full of senior citizens from their town? What about from a different community across the state? What might be different, group to group, and why?

- Explain that Snapshot: Climate can help them to understand how their own community’s experience of climate change fits into broader patterns around the state and across the South.

II. Snapshot: Climate

[20–30 minutes]

Pass out copies of Snapshot: Climate, if students don’t already have them.

Give each student 10 minutes to flip through the issue and pick a photo that specifically resonates with them. Then, ask them to do a “pair & share” with the person next to them about why they picked that image.

Finally, open up the conversation to the full class. You might ask questions like:

- Does anyone want to share the image they chose, and why?

- How many of you chose images that reminded you of your own life/community? What felt similar? (Answers might include: flooding; the destruction of houses and infrastructure; invasive species; pollution; environmental racism . . . )

- Did you see any images of climate change that felt very different from what is familiar to you? (Answers might include: the intensity of how climate change is manifesting; the visibility of its impact; ecological specifics . . . )

- What did these images make you feel?

- Do you think images like this have the potential to change how people think about climate change? Why or why not?

Ask students to turn to the entry on Goose Creek, NC on page 27. Have a student (or a few) read the one-page essay aloud to the class.

After students have heard the essay, highlight for them how the authors (Painter, Roach, and Emanuel) describe Native American communities working to “re-story” the world as a key part of combating climate change. Ask students what they think that the authors mean by this play on “re-storing.”

Students will sum this up in their own words. Affirm for them that the authors are trying to remind us that when we have stories about the natural world; when our own identity feels invested in a particular place; when we feel connected to nature; and when we start to see nature as a part of our community’s past, present, and future, we are going to take care of it in a radically different way.

Explain to students that you will now be doing an exercise in “re-storying” the natural world.

III. Writing Climate Change

[20–30 minutes]

1. Ask students to close their eyes and imagine one image that they would choose to capture climate change in their own community, family, or personal experience. They don’t have to have a photograph of this image, though they may—for this assignment, they will just be describing it in words. Explain to students that for this exercise, they won’t be turning anything in and they won’t need to describe their image or share their writing with the entire class.

Give examples so that students can start to imagine what is possible: e.g. “This could be an image of your grandmother in her kitchen, cooking vegetables from her garden; or a grove of trees impacted by drought, or invasive insects, or fire; or a friend fishing; or a plant, or a body of water, or an animal . . . any part of the local environment that feels symbolically important to you.”

- In one short paragraph, ask students to describe the image they are picturing. Who or what is in the image? What do viewers need to know to understand what they are seeing? How does climate change connect to this image?

- In a second paragraph, ask students to describe why this image is so powerful to them. What memories does it connect to? What feelings does it stir up for them?

- In a third and final paragraph, ask students to describe why they would like other people to see this photograph. What would it teach other people about what climate change looks like in your life? Do you see this image as a call to action?

IV. Wrap Up

1. Ask students to reflect on this experience:

- What did it feel like to sink yourself into one image like that?

- Did anything surprise you about your own responses to these questions?

- Do you think your siblings or neighbors would pick a similar or dissimilar image?

2. Affirm that although your students’ experiences with climate change are all unique to their specific life story, family background, and experiences in the environment, they also fit into a broader pattern of climate change throughout the American South.

3. OPTIONAL Homework

Option A. Explain to students that they will have an opportunity to take some real pictures and continue to experiment with this kind of imagery and writing with a specific image. If you are setting aside time in another class session to workshop entries together (As outlined in Lesson Plan: 2: Visualizing Climate Change), you can walk them through the Visualizing Climate Change Assignment, which will help them take a photo and draft an artist’s statement.

Option B. If you’d like to continue the conversation but not through photo submissions, you may want to assign the Climate Change Interview Assignment, which has students interview an older friend, family member, or community member about their experiences with and attitudes about climate change.

“Visualizing Climate Change”

Take-Home Assignment

1. Look through Snapshot: Climate again, and pick out just 2–4 photographs that particularly speak to you. Think about why these photographs are so compelling. Write down just a few words that sum up the impact of these images (and the artist’s statements that accompany them).

2. Using these words as your guide, begin to brainstorm what you might photograph. This could be a staged photo with a family member or friend, a photo of a place, or a photograph that is necessarily spontaneous—of a rainstorm, or a wild animal.

3. After you’ve thought of a few possibilities, get out there and start snapping pictures! It may take days (or weeks) for you to get a few shots you are happy with.

4. When you have an image (or images, plural) that you want to work with, you can sit down to draft an initial artist’s statement. This should be 250–400 words. At this point, it can be rough! But here are some guiding questions it can address:

a. What is the story this picture tells?

b. Why is that particular story important to you?

c. What might someone not know about this picture if you didn’t tell them?

d. How do you think this image will connect with the experiences of people outside your community?

e. Did this image surprise you? Is there anything they capture that you did not intend, or did they make you notice something new?

5. Your image and drafted artist’s statement are now the foundation of a submission to the Southern Cultures photo contest. Follow your instructor’s directions for specifics about whether to bring these to class for a workshop, or to turn them directly in.

Climate Change Interview

Take-Home Assignment

This exercise is designed to encourage students to get curious about the experiences and perspectives of other people in their community on climate change.

For this assignment, you will interview an older family member, friend, or community member about their experiences with and attitudes towards climate change. You don’t have to record your conversation (though you might choose to, if your instructor has walked you through how to get permission from your interviewee.)

Instead, you will be asked to summarize your interview in a paragraph and then to reflect on what you heard and learned in a second paragraph.

Potential Questions to Ask During the Interview:

About childhood:

- Did you grow up here in ____?

If yes,

- Did you spend a lot of time outdoors as a child?

- What was your relationship like to local waterways, forests, fields, animals, etc?

If no,

- How do you understand climate change to be impacting the place where you grew up?

- What was your impression of the landscape/environment when you first arrived in ____?

About their relationship to the environment:

- Do you spend a lot of time outside now? Why or why not?

- What are the things you most enjoy about nature where you live?

- Have you noticed any changes in the environment since you were a kid or a teenager? In the landscape, weather, animals, or plants?

- How do those changes make you feel?

About their understanding of climate change:

- What do you know about climate change?

- How did you learn what you know?

- How often do you think about it now?

- What brings you hope when you think about the future of our climate?

- What would you like younger generations to understand about the environment?

Feel free to add your own questions, and to let the conversation flow!

Follow your instructor’s directions about how and where to submit your reflection.

Lesson Plan 2:

Visualizing Climate Change

Overview

This lesson gives students the opportunity to workshop their own photograph(s) and write about climate change with fellow students. It is designed for students who are submitting entries for the Southern Cultures Photo Contest.

Essential Questions

- What is the main message you want to convey about climate change in your community?

- Why is this aspect or impact of climate change so important?

- How does this fit into broader patterns throughout the South?

- How can you most impactfully tell this story through images and words?

Materials

Copies of Snapshot: Climate for each student

Duration

60–90 minutes

Preparation

Students should come to class with: a photograph (or several!) that represents climate change to them, and with a drafted artist’s statement (of roughly 250–400 words). They can show classmates the image on a computer or a phone, but should bring 3 printed copies of their artist’s statement if possible.

Optional: If the instructor has time, they may ask students to send them images ahead of time and compile them into a simple slideshow. (In this case, instructors may want to stress that it is optional so that students don’t feel forced to share.) If the instructor has time and the office resources, they may choose to print the images out and hang them around the room in a drafted “gallery” display—this will make for a more kinesthetic experience for students during the day’s exercise.

I. Warm-up Conversation

[5–10 minutes]

Ask students to describe the experience they had of taking this photo and drafting this artist’s statement. How did it make them feel? Was it difficult to choose one thing, or did they know exactly what they wanted to take a picture of? Was their picture planned, or spontaneous?

II. Optional Exercise

[10–15 minutes]

This exercise is designed to be a warm-up exercise if the instructor has a slideshow or “gallery exhibit” around the room of student images.

Stress that this is meant to be a constructive conversation and review class expectations for being a supportive community that provides respectful commentary to each other’s works-in-progress. Explain that the purpose of this exercise is to help students understand what their art may mean to them, versus how it may be perceived by others.

If using a powerpoint: Flip through the images one by one, and ask students to call out one-word responses of things that come to mind. These words might be descriptive of the scene, like “parched” or “stagnant,” but they may also be emotional words: “peaceful,” “balanced,” “ominous.”

If you have spread printed images around the room: Give each student a small stack of Post-Its, and have them do their own “gallery walk” around the room, leaving 1–3 Post-Its next to each image with a few words of response.

After this exercise, ask students to think carefully about the image they brought to class today, and about what they want it to evoke for people. Explain that if there is dissonance between what the image represents for them and what strangers might see when they first look at it, their artist’s statement is a chance to provide context and help the viewer to see the story they are trying to tell.

III. Small Group Work (40–50 minutes)

Break students into groups of 3 or 4. Have every student look at and read through their classmates’ work. This is why students brought print-outs of their artist’s statements—to share with their partners. Ask them to take notes on how the image makes them feel or what it evokes for them, what the artist’s statement reveals to them, and what questions they are left with. Give students 10 minutes to look at each other’s work.

Then, explain to students that you will be setting a 10-minute timer. For 10 minutes, the group will be focused on giving feedback to just one particular student. Stress that if they think they have run out of things to talk about, they haven’t! It’s just an opportunity to dig deeper.

Set the timer again for the next student, repeating until every student has been covered in each group.

IV. Recap

[5–15 minutes]

Ask students to recap how that experience was. Did it help them to see their own image through their classmates’ eyes? Did they see things in each others’ work that resonated with them, or changed how they wanted to approach their own submission?

Leave by encouraging students to submit their entries for the photo contest in order to put them in conversation with other images from this community. If the instructor would like, there may also be a requirement to turn in final drafts of submissions for course credit.

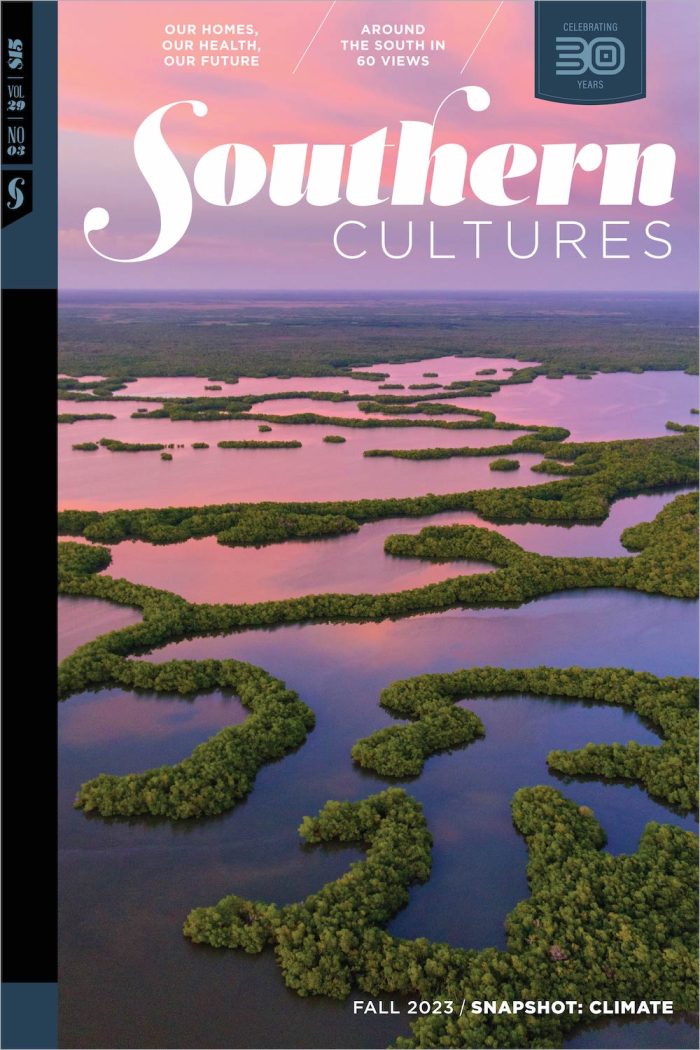

Header image: Prescribed burn, Bullock County, by Chuck Hemard. Auburn, Alabama, 2017.

This project was generously supported by the North Caroliniana Society, Carolina Public Humanities, and Carolina K–12.