I’m grateful to the people willing to share with me, and to be able to contribute in my own small way. I’m trying to remain hopeful, to not look away, to act with compassion and purpose against our shared challenging reality. — Brandon Dill

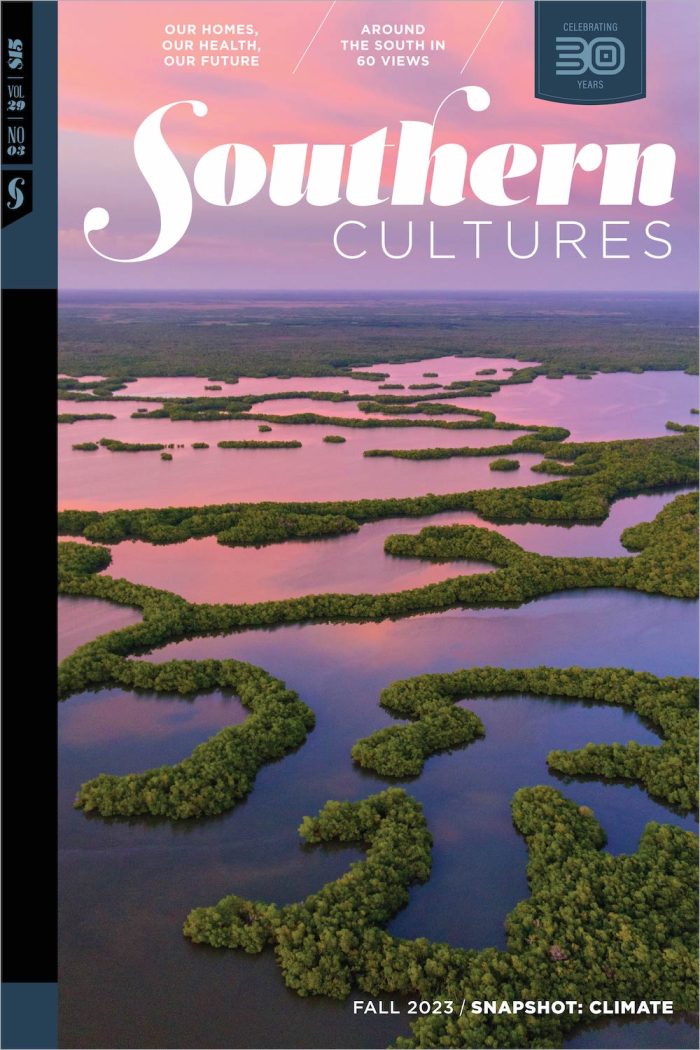

The Snapshot: Climate issue features more than 60 photographs and accompanying short reflections from artists, activists, photojournalists, and scientists to provide a “snapshot” look at climate impacts across the South. As climatologist Angel Hsu writes in the issue’s introduction, we set out with this issue to make the “invisible visible,” “using images and words from the contemporary South to show the ubiquity of climate change and how we all are experiencing the phenomenon.”

View 14 of the 60 snapshots in the following feature. Twenty-five photographs from the issue will also travel to galleries across the South over the next year. Find the full list of events here and join us on the road.

High Springs, Florida

Jenny Adler | Florida manatees swim in a freshwater spring along the Santa Fe River, 2019.

Florida is home to more than one thousand freshwater springs that are direct connections to the underlying aquifer, which supplies drinking water to more than 92 percent of Floridians. They are also home to unique wildlife, including the Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris), a subspecies of the West Indian manatee. Manatees come into the springs in the winter to stay warm when the ocean temperatures drop below 72°F, because, unlike seals and whales, they lack a true blubber layer.

Manatees swimming through clear water and sunbeams makes for a beautiful image. But as an ecologist who knows what the springs used to look like, I see something very different.

For ten years, I lived in north Florida and documented these springs year-round—and accidentally documented the decline of these ecosystems. The most noticeable change underwater has been the disappearance of native grasses and the proliferation of nuisance algae. Springs have transitioned to this algal-dominated state for a variety of interconnected reasons, including overextraction of water to serve Florida’s growing population (the state is now the nation’s third most populous), extreme weather and climate change, changing rainfall patterns, and pollution from farms and households.

This algae is not on the menu for manatees, who can eat up to 10 percent of their body weight in plants per day—this can be upwards of 100 pounds of vegetation. As the grasses disappear, manatees have very little left to eat. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, 1,100 manatees died in 2021, now the deadliest year on record. Many of these deaths were due to starvation as seagrass and other native grasses disappeared.

Manatees swimming through clear water and sunbeams makes for a beautiful image. But as an ecologist who knows what the springs used to look like, I see something very different.

Princeville, North Carolina

Marquetta Dickens with support from Turcois Vazquez and Justin Cook | Kendrick Ransome and Marquetta Dickens in the Tar River at Shiloh Landing, 2019, photo by Justin Cook

Princeville, North Carolina has been home to my family for a century. It is the oldest town in America founded by formerly enslaved Black people, who, at the end of the Civil War, fled to land nobody else wanted in the Tar River floodplain. As a child, I never knew my community’s historical importance and didn’t understand the pressure my grandmother, Delia Perkins, faced as mayor when Hurricane Floyd caused the Tar River to overtop our levee and flood Princeville in 1999. When other commissioners voted to dissolve the town, she cast the deciding vote to keep Princeville right where it originated.

The American story is incomplete without Princeville’s story—the story of captivity, segregation, and survival. Princeville is a symbol of freedom to those who endured the unimaginable.

After Hurricane Matthew flooded the town in 2016, I became more aware and involved in advocating for and redeveloping my community. I cofounded a community development corporation, Freedom Org, to address systemic harms to Black people and to promote Black autonomy and self-sufficiency. We address climate change by connecting Black people back to the land through programs that teach regenerative farming, and we are working toward our goal to help build flood-resistant affordable housing.

The people of this town created solace in a hostile climate by building a community with their bare hands. Now we face being washed off the map due to climate change. Climate warming allows hurricanes to hold more moisture, release more rain, and linger so they cause more flooding. Scientists in North Carolina say we can expect more storms like Floyd and Matthew, and our flawed levee can’t prevent flooding. Many call us resilient, since we have endured slavery, racial violence, Jim Crow, and repeated flooding by the Tar River. I echo Angela Davis, PhD, who said, “Black people are resistant people. It is a necessity, not a choice. It’s what Black people have to do to assert their own dignity and simply survive.”

To many white Americans, historians, and storytellers, Princeville is considered Black history, not American history. The American story is incomplete without Princeville’s story—the story of captivity, segregation, and survival. Princeville is a symbol of freedom to those who endured the unimaginable. Because of its importance to the American story, the town must do more than survive: Princeville must thrive.

Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana

Virginia Hanusik | Port Eads Lighthouse, 2020

The coastal deterioration of Louisiana is due in part to the leveeing of the Mississippi River and our attempt to control its natural course. As development along the river’s banks increased along the one-hundred-mile stretch between the Port of New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico in the nineteenth century, frustration grew from the frequent silting up of its outlets, making parts of the river unnavigable. To solve this, a jetty system designed by engineer James Buchanan Eads was constructed at the mouth of the river, narrowing the main outlet and restricting the natural flow of sediment.

Architecture and infrastructure communicate larger societal beliefs and values about living with the natural world.

After the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the Army Corps of Engineers was tasked with carrying out massive flood control measures throughout the river’s watershed. By the latter part of the twentieth century, the coastal parishes of Louisiana, including Plaquemines Parish, seen here, were reduced to a fraction of the land masses that they had once been. As sea level rise threatens the physical fabric of the coasts, how will our emotional connections to these landscapes change, and what impacts does that have on communities farther inland?

Architecture and infrastructure communicate larger societal beliefs and values about living with the natural world. By focusing on the landscape and infrastructure of South Louisiana, my images are meant to convey how we’ve altered the land through these engineering measures and subsequently how we’ve chosen to protect some communities over others. Showing the top of the Port Eads Lighthouse, where the Mississippi River meets the Gulf of Mexico, this view is a reckoning of the precarious futures of coastal living and how we inhabit the transitional space between land and water.

Baker County, Georgia

Anna Gage Norton | After the storm, Ichawaynochaway Creek, 2020

This patch of land along the Ichawaynochaway Creek in Baker County, Georgia, was an inviting mixed hardwood forest until Hurricane Michael’s path crossed it in 2018. Michael was the first of its kind, a Category 5 upon landfall, to hit the panhandle of Florida and southwest Georgia, and we have seen an ever-increasing number of similarly intense storms since. We are becoming more and more familiar with the wake of destruction, but not so much with the process that follows. The little that is covered in news cycles about repair processes often focuses on urban areas and human development. We see and read little about the effects on the natural landscape, the path forward, and why it matters.

My father grew up on this land where my grandparents farmed soybeans, peanuts, and pines, along with the other usual suspects—cotton, corn, wheat, and watermelons—but once fallow, the fields gradually fell to disrepair. For the last sixteen years, my family has been returning the farm to the native longleaf pine forest to promote biodiversity for a sustainable ecosystem. With a lifespan of three hundred to four hundred years, this native conifer once covered the southeast from Texas to Virginia. Its decline, due to decades of logging, development, and fire suppression, continues to this day with just three percent of peak range remaining. Able to withstand severe windstorms, resist pests, tolerate wildfires and drought, and capture carbon from the atmosphere, longleaf are naturally more resilient to climate extremes than other southern pine species and therefore the best candidate for restoration to fight the effects of climate change.

We see and read little about the effects on the natural landscape, the path forward, and why it matters.

Significantly transformed after only a short time, my family’s farm is home to a growing number of native plants and animals, including the protected gopher tortoise, a keystone species. Approximately 360 other species, several of which are also legally protected, threatened, or endangered, use gopher tortoise burrows. Among these are the fox squirrel, a predominantly ground-dwelling subspecies approximately twice the size of the common gray squirrel. Presence of this indicator species is good news, signifying that the understory—the essential plant life growing between a forest’s ground cover and canopy—is sufficiently open and the habitat is healthy.

Wiregrass was present prior to restoration, but only in small amounts. We introduced seeds in areas where it had been absent, and it has also since flourished on its own. Like longleaf, wiregrass evolved with frequent, low-intensity fires started by lightning strikes. Its chemical makeup, along with its physical structure of hollow, round blades that draw heat, allow it to spread fire in service of its natural cycle.

During the wet season in December of 2020, two years after the storm, tree-planting crew members led by Louie Padilla of Moultrie, Georgia, moved methodically across a section of land on the western side of the creek that was razed by the storm. They carried bare-root longleaf seedlings, pulling one at a time from sacks on their backs to plant by hand every six feet. Seedlings are placed into holes made with a dibble, a long hand tool similar to a shovel, that is then used to repack soil around the roots.

The new plantings will help support the overall habitat for the entire food web and a rich and essential ecosystem. Ongoing prescribed burns here and on the rest of the property will also ensure that the understory remains open and the evergreens thrive, further extending the longleaf community that once dominated this land.

Everglades, Florida

Lisette Morales McCabe | Betty Osceola prays in the waters of the Everglades, 2021

The Everglades are as mysterious and alluring as they are welcoming, with vast skies and glittering waters. Miccosukee grandmother Betty Osceola, 55, was born and raised in the Everglades, where she still resides. Over the past few years, she’s been leading prayer walks across Florida to bring attention to the many threats to this unique ecosystem caused by human activity and climate change. The Everglades is the source of drinking water for eight million Floridians. Sea level rise and changes in rainfall may cause droughts and floods with disastrous effects.

We are the earth, we are the water, we are the wind, and we are one with nature. We need to care for everything.

Betty is devoted to her family and community and dedicated to educating the public about the importance of connecting with nature to promote personal and global healing. Her Indigenous-led prayer walks have been transformational in my personal and professional life. I attended my first one, a five-day walk across the Everglades on US Highway 41, in March 2017, six months after a long recovery from major surgery and weeks-long hospitalization. After this illness, I felt disconnected from myself and the world and experienced a need to be closer to the natural world. On the prayer walk, I thought about ways to connect to nature through my photography practice and to amplify voices around climate issues.

In the early hours of January 8, 2021, my husband, Sean, and I met Betty at Buffalo Tiger Airboats Tours, the company she operates near Miami as an airboat captain. The three of us boarded her airboat and headed deep into the waters of the Everglades to begin a two-day collaborative photo project that resulted in this photo and other images that Betty used in a social media campaign, #DefendTheSacred. In that, and in all of her work, Betty reminds us that we are the earth, we are the water, we are the wind, and we are one with nature. We need to care for everything.

Colbert and Lauderdale Counties, Alabama

Natalie Chanin | The Tennessee River below Wilson Dam spillway, 2022, photo by Robert Rausch

As a child growing up in the Tennessee River Valley, I didn’t know, or fully understand, that the entire state of Alabama is a watershed. From the streams and creeks that flow to the Tennessee River in north Alabama to the river basins that meet the Gulf of Mexico, aquifers, creeks, rivers, and underground lakes populate and crisscross the state.

The Tennessee River is the fifth largest watershed in the United States and is considered one of the most diverse aquatic ecosystems in the world. It was also the playground of my childhood. I grew up camping every weekend on a small lot as far north and as west as you can go and still be in the state of Alabama, at a confluence where Bumpass and Second Creeks meet the river—a stone’s throw from the small town of Waterloo, Pickwick Lake, and the Tennessee River channel. I learned to swim in the shallows as soon as I could walk. Every summer of my childhood, I helped my grandfather run a trotline, pulling up the string of hooks, adding tightly balled white bread as bait on empty ones, and gathering the bounty of catfish, bream, crappie, and other fish the river provided. This weekly catch would be cleaned on a backyard picnic table and turned into family meals that we devoured with sides of hush puppies and freshly made coleslaw, followed by my grandmother’s delicious lemon meringue pie.

When I couldn’t remove the smell of sewage from my wet bathing suit, I decided to stop swimming in the river.

In my early teens, I learned that the river—which had saturated our lives and bodies—was filled with mercury. That means the fish that fed our family gatherings were also filled with mercury. Three decades later, the Tennessee River was deemed the fourth most polluted river in the nation. That same year, when I couldn’t remove the smell of sewage from my wet bathing suit, I decided to stop swimming in the river. It was a hard and heartbreaking decision to remove myself from the water—so connected to memory and adventure. Recent studies suggest that the Tennessee contains more microplastics than any other river in the world—jeopardizing our biologically diverse ecosystem.

Today we see a swell of people committed to stewarding our creeks, streams, and rivers. Important organizations like the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area, Tennessee Riverkeeper, Tennessee RiverLine, Singing River Trail, Keep the Tennessee River Beautiful, and American Rivers are leading the way for recreation, connection, and community. We can track pollution and those who pollute through sites like “What you CAN‘T see in the Tennessee River”—a story map that documents our progress.

As a constituent of the river, it’s my responsibility to hold our institutions accountable for keeping our watershed clean and accessible. It is my hope and commitment to help create a place where the next generations can build the same adventures, memories, and stories my family built on the banks of this beautiful river.

Myrtle Beach, South Carolina

J Henry Fair | Morning Beachgoers, 2015

Imagine living near the shore. The ocean is rising at an accelerating rate. Walls are built at great cost, and their construction contributes to the climate crisis (concrete is the third largest industrial cause). Soon it is clear that the ocean will top the barriers and the order is made to move the city and everyone in it. This unbelievable scenario is now. Indonesia has begun the process of relocating its capital, Jakarta, the second largest city in the world.

Ironically, just as these realities counsel a move of infrastructure away from the ocean, coastal population density and infrastructure investment on the shore are rapidly increasing.

I’ve spent ten years photographing sites around the world for my Coastlines project, including in South Carolina, where I was born. This series is a portrait of coasts around the world before the major impacts of climate change and ocean rise take effect. Ironically, just as these realities counsel a move of infrastructure away from the ocean, coastal population density and infrastructure investment on the shore are rapidly increasing.

Historically, ports were logical locations for communities. The ocean provided food, transportation, mineral resources, waste disposal, and water for myriad purposes. Comprising less than 10 percent of our land area, coastal counties house 19 percent of our population today and are responsible for 45 percent of our GDP—concentrations that are projected to increase.

Recreation is also a major attraction along coastlines, with its own infrastructure and pollution problems. Large hotels and resort complexes are built, replacing the dunes and mangroves that protected the shore, and pollution from these populations fouls the water, poisons the ocean life, and promotes algae blooms. Roads and parking lots replace the permeable earth and promote erosion, and are the source of toxic runoff.

Climate change is increasing storm activity and ocean rise, which directly impacts littoral areas. Natural shoreline features such as beaches, sand dunes, marshes, and mangroves act as buffers to weather systems, pliably absorbing the impact of storms and high tides and thus protecting the hinterlands.

Meanwhile, coastal cities are already piling up sandbags and building barriers and gates to protect from ocean rise.

Austin, Texas

Matthew Busch | Texas Heat, Barton Springs, 2022

July 2022 in Texas brought relentless, all-consuming heat. All things being unequal, many of us escaped into air-conditioned homes, offices, and cars. If we lived close enough to a pool or a place like Austin’s Barton Springs, we dove in. But those who live and work outdoors or don’t have access to air conditioning faced the full force of the summer—blistering even by Texas standards, 279 people would die heat-related deaths by the end of the year. Houston, Austin, and San Antonio all logged record July temperatures; the state also set a new record for peak electricity usage, then broke it six times before month’s end. The climate is changing so rapidly that some of our communities will become unlivable in our lifetimes and many others will almost certainly become unbearable, further emphasizing social inequality.

The spaces at the center of community life, which have often been saddled with historical inequities, are, today, on the frontlines of the climate challenges we face. In Austin, Texas, Barton Springs is at the very heart of the city. Early city leaders transformed the largest in this set of natural springs emanating from the Edwards Aquifer into a pool in the 1920s. It is now one of the city’s leading natural attractions and a treasured respite from the summer’s oppressive heat. But equal access remains tenuous. A majority of Austin’s Black population still lives in an area consigned to Black residents by segregationist policies in the 1920s. That area, East Austin, is still located a considerable distance from Barton Springs, which has long been a community hub for white Austinites.

Starting in 1960, young Black women like Joan Means Khabele and Azie Morton staged “swim-ins” at the then-segregated Barton Springs Pool, successfully leading to the pool’s integration in 1962. The City of Austin has more recently changed the name of a road leading to the pool from Robert E. Lee Road to Azie Morton Road (Morton was also the first Black US treasurer). And after the death of Khabele in 2022, the Austin Parks and Recreation Department held a ceremony to honor her at the pool. Although these events signal a shift away from Austin’s racist past, longer shadows of discrimination remain in the city.

When the world we live in is rapidly re-creating itself due to climate change, access to those vital spaces is more important than ever.

Easy access to Barton Springs’ cooling waters on a hot day may not seem like the most pressing issue. But one of Austin’s early Parks and Recreation leaders once justified the city’s plan to promote its green spaces because those green spaces were necessary for people to thrive. Recreational spaces are spaces in which one can re-create themselves for the better, they said. When the world we live in is rapidly re-creating itself due to climate change, access to those vital spaces is more important than ever.

McDowell County, West Virginia

Roger May | Surface mine between Welch and Northfork, June 2019

As of 2014, Governor Jim Justice owned 70 mines in five states. I photographed this site in McDowell County for an attorney who represented clients who had not been paid by Justice and were suing. I have photographed a number of surface mine sites in West Virginia and Kentucky over the years in an effort to add to the documentation of this horrific practice.

Surface mining, often called mountaintop removal mining, is the most destructive form of mining as it completely blows up mountains to get at the coal beneath.

Surface mining, often called mountaintop removal mining, is the most destructive form of mining as it completely blows up mountains to get at the coal beneath. The excess material, or overburden, is then dumped into adjacent valleys, choking off the natural flow of streams and drainage. Once these mountains are blown up, they can’t ever be replaced. Since West Virginia became a state in 1863, coal has wielded incredible power in every aspect of life here, especially in politics. I can’t comprehend how any governor who claims to love West Virginia as much as he does can not only allow this type of destruction, but profit from it to the tune of billions of dollars while everyone downhill and downstream suffers the repercussions.

Norfolk, Virginia

Michael O. Snyder | The Wild West on Chesapeake Bay, 2021

We have to move away from the coastlines in a way that protects both marshes and people. But how are we going to do that?

Skip Stiles, executive director of Watershed Watch, stands in the streets of Norfolk, Virginia’s low-lying Larchmont neighborhood as the Lafayette River spills over the battered seawall and into the community. “It’s like science fiction meets the Wild West,” says Skip. “It’s both scary and fascinating just how fast sea level rise is happening. There’s almost always fish and crabs living in this street. And you see these plants creeping in?” He points to the lawn to our left. “That’s spartina grass. The marsh is trying to migrate. And it would, except that it has nowhere to go. We’re blocking its path. We’ll probably lose 50 to 80 percent of our vegetated wetlands by the end of this century for that very reason. And these houses, they’ll never sell. It costs $1.2 million to elevate a $250,000 home 1.5 feet. The math doesn’t make sense. So, these people are trapped. It’s a sticky issue. We have to move away from the coastlines in a way that protects both marshes and people. But how are we going to do that? Like I said, it’s the Wild West. We’re in uncharted territory.”

Morgan City, Mississippi

Vanessa Charlot | Retired Army veteran Terrence Davenport stands in a cotton field on the former Quito Plantation, February 2022

In 2021, I traveled to the Mississippi Delta to document the devastating impacts of climate change on agricultural Black life. In this work, I began to understand the deep connection between Black Mississippians, their environments, and their sense of place. The idea of place has always been a complicated one for Black folks in the South, and Mississippi, a place that represents home, family, and a sense of belonging for many Black southerners, has also been historically hostile and violent towards the Black bodies that inhabit it. The repurposing and disrupting of the natural landscape and its ecosystems for the social and financial benefit of the white privileged class through the labor of enslaved Africans has played an integral part in how climate change directly impacts Black Mississippians today. For Black families in the Delta, who are already facing difficult socioeconomic conditions, climate change has become a compounding threat, with hotter temperatures, flooding, and other extreme weather that directly impacts livelihoods.

Climate change has become a compounding threat, with hotter temperatures, flooding, and other extreme weather that directly impacts livelihoods.

Through the eyes of retired US Army veteran Terrence Davenport, the grandson of a former sharecropper on the former Quito Plantation in Morgan City, I began a visual ethnography of Black rural life in one of the most agriculturally rich, and most environmentally vulnerable, areas in the South. This two-month project captured the life and precious moments of the Davenport family, who were gifted the cotton fields after many decades of laboring on the Quito Plantation. Terrence, a third-generation Mississippian, shared his concern about how the rapidly changing environment may impact whether his family will be able to stay and maintain this generational connection to this land or if they will ultimately have to move North, also becoming part of the long legacy of historical violence Black Mississippians have suffered.

Little Rock, Arkansas

Derek Slagle | View from Clinton Presidential Park Bridge, 2019

Home evacuations, animal relocations, and sandbagging occurred from Fort Smith, through Dardanelle, to the capital city of Little Rock, and then downstream to Pine Bluff.

In 2019, heavy rainfall swept across the central United States, resulting in major flooding in Oklahoma. Water from the flash floods in Oklahoma continued downstream and added to already high water levels from previous rains along the Arkansas River. Repeated thunderstorms and additional rain fed into streams that turned the Arkansas River into a flood, causing nearly $3 billion in damages and killing five people. Home evacuations, animal relocations, and sandbagging occurred from Fort Smith, through Dardanelle, to the capital city of Little Rock, and then downstream to Pine Bluff. The National Guard shut down local parks and roads that ran along the river. Multiple businesses permanently shuttered their doors as floodwaters made entire areas of the town accessible only by boat. The US Army Corps of Engineers was brought into my town, Little Rock, as the height of the crests exceeded that of the levees and flooding forced water back upstream into the tributaries that feed into the Arkansas River. The US Geological Survey noted that this was a once-in-a-two-hundred-year flood, as the major parts of the downtown area along the waterfront were being enveloped and the river saw its highest point in recorded history. I specifically remember the water working its way up to where it nearly touched the bottoms of the bridges that traverse the river. Governor Asa Hutchinson declared a statewide emergency and eventually noted that the flooding resulted in economic losses of $23 million per day.1

Hazard, Kentucky

Austin Anthony | Gospel Light Baptist Church, July 31, 2022

In July 2022, several creeks and hollers in Eastern Kentucky flooded after the region received fourteen inches of rain in three days. Thirteen counties were declared federal disaster areas. Small creeks became torrents, ripping houses off their foundations and depositing the debris miles away. Low-lying areas, like Jackson, Kentucky, became temporary lakes, with standing water taking days to recede. Thousands of buildings were destroyed and thirty-nine people were killed.

Thirteen counties were declared federal disaster areas. Small creeks became torrents, ripping houses off their foundations and depositing the debris miles away.

Gospel Light Baptist Church in Hazard began taking people in and organizing supplies the day after the flooding. In the following days they would remove the pews in the nave and replace them with cots. Among those who took shelter in the church were Johnny Mullins Jr. and his grandson Tyrone Cotton, four months old. Mullins’s daughter and son-in-law also stayed in Gospel Light.

It is strongly speculated that the area’s history of resource extraction contributed to the disaster. Former federal mine safety engineer Jack Spadaro told the local press that strip mining in the region removed soil and vegetation that would have helped with water retention. Without deep roots to take up some of the rainfall and maintain soil integrity, the water that fell on the mountains encountered little resistance on its way to the creeks.

Waverly, Tennessee

Brandon Dill | Playground View, 2021

On a Saturday in late August 2021, twenty-one inches of rain fell on the hilly countryside of rural Humphreys County, Tennessee. Soon, a wall of water was racing down hills and through valleys toward the small community of Waverly, where it would quickly swallow whole sections of the town like a tsunami.

Clear, ankle-deep creeks where children played became torrents of deadly brown water carrying them away. Cars, buildings, and entire roads were suddenly erased or snarled together into grotesque sculptures. Loved ones were pulled from each other’s arms as the violent water swept them from their homes. Twenty of the town’s 4,100 residents lost their lives in the flood. No one was unaffected by the disaster.

I’m grateful to the people willing to share with me, and to be able to contribute in my own small way. I’m trying to remain hopeful, to not look away, to act with compassion and purpose against our shared challenging reality.

In this photo, a playground is visible through a home in Waverly, the walls of which were knocked down by the powerful flash flood. Many of those killed, including children, lived in this neighborhood. The water came too suddenly for most to evacuate. Some clung to each other inside their homes only to be wrenched apart and carried away by the raging water.

Then, as quickly and indifferently as it came, the water left. And it left the people of Waverly to grieve the incomprehensible losses wrought by the storm, a previously unprecedented weather event scientists say is made more common by climate change.

While photographing in Waverley, I was conflicted about which images to make and which to share. I worry about exploiting the pain of others, about adding to the endless forgettable heap of disaster porn. A colleague agreed, saying they felt like a ghoul walking around as an outsider through such catastrophe, amid so much intense and intimate suffering.

It didn’t take long, though, to learn by thoughtfully listening that many of the people most affected were also the most eager to share, who felt a need to be heard, to have their stories witnessed. I’m grateful to the people willing to share with me, and to be able to contribute in my own small way. I’m trying to remain hopeful, to not look away, to act with compassion and purpose against our shared challenging reality.

And I understand this reality is the story. It must be told. The dangers of climate change touch us all, indiscriminately.

JENNY ADLER, PhD, is an underwater photojournalist based in California. Her work is informed by her scientific background, and she uses her imagery to communicate science and conservation. She specializes in underwater photography and is a trained freediver and cave diver with extensive experience working in extreme and remote underwater environments. jenniferadlerphotography.com

MARQUETTA “COACH Q” DICKENS a former professional basketball player and esteemed career coach, is the innovative founder of Freedom Org, a community development corporation dedicated to holistic solutions for underresourced communities. Leveraging her advanced education in student affairs and college counseling and parks, recreation, and leisure facilities management, Dickens fosters environments that nurture personal growth, embodying a vision of a world where everyone is equipped to carve their own path to greatness.

JUSTIN COOK is a photographer, journalist, and artist based in Durham, North Carolina, who tells stories about climate change. He is a 2006 graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Journalism and Mass Communication. He is a multiple Pulitzer Center grantee, and his work has been funded by the Solutions Journalism Network Climate Solutions Fellowship and the North Carolina Arts Council. He has been honored by the Magenta Foundation, POYi, the Society of Environmental Journalists, the Society of Professional Journalists, and American Photography. justincookphoto.com

TURCOIS VAZQUEZ is a writer, historian, and burgeoning Africologist whose research centers around reparations, neocolonialism, and African history. She has studied linguistics, West African history, and genealogy at the University of Ghana and has served as an NAACP legislative fellow, where she gained a firsthand look at how activism impacts legislation. Her work and research inform the fundamental principles of cultural preservation and protection that she brings to her role as historic and cultural preservations director for Freedom Org.

VIRGINIA HANUSIK is a photographer whose work explores the relationship between landscape representation, climate change, and the built environment. Her projects have been exhibited internationally and supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation, Pulitzer Center, Graham Foundation, Landmark Columbus Foundation, and Mellon Foundation. She lives in New Orleans, Louisiana. virginiahanusik.com

ANNA GAGE NORTON received her MFA in photography in 2005 from Tyler School of Art, Temple University. She was a 2021 recipient of a Puffin Grant, and her most recent work is featured in Aint–Bad, Murze Magazine, and Oxford American‘s Eyes on the South. A native of South Georgia, she now lives in western North Carolina, where she continues her work in photography, videography, and education. annagnorton.com

LISETTE MORALES MCCABE is a multicultural Nicaraguan-born artist and photographer based in Southwest Florida. Her work focuses on identity, gender, ecology, and food heritage and has appeared on PBS, NPR, Univision, Bloomberg Businessweek, and ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America. She is a member of Diversify Photo, The Authority Collective, WOPHA, and Voices of the River of Grass.

NATALIE “ALABAMA” CHANIN is the owner and designer of Alabama Chanin. She has a degree in environmental design with a focus on industrial and craft-based textiles from North Carolina State University and has worked as a fashion designer, stylist, and costume designer. In 2000, she returned to her home to begin the sustainable work that has become Alabama Chanin. The organization now includes Alabama Chanin Collection, The School of Making, and Project Threadways—the not-for-profit arm working on craft preservation.

ROBERT RAUSCH grew up in the South and studied photography at Parsons School of Design in Paris, France, before obtaining an MFA from Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California. His photography can be seen in the New York Times, Travel & Leisure, Garden and Gun, Southern Living, Ladies Home Journal, Elle, American Craft, Cottage Living, and Veranda, to name just a few. Rausch currently lives on a small farm in north Alabama. rrausch.com

J HENRY FAIR is a photographer, environmental activist, and cofounder of the Wolf Conservation Center in South Salem, New York. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, he currently lives and works in New York City. Recent books include Industrial Scars: The Hidden Costs of Consumption, and from his Coastlines series, On the Edge: From Combahee to Winyah.

MATTHEW BUSCH is a visual artist and writer living in Austin, Texas. His work documents a broad range of issues, including the environment, mental health, migration, and community in the United States and abroad, and has garnered national and international acclaim. Busch works full-time telling stories about the people and issues integral to his home state of Texas.

ROGER MAY is an Appalachian American photographer and writer based in Alum Creek, West Virginia. He was born in the Tug River Valley on the West Virginia and Kentucky border, in the heart of Hatfield and McCoy country. His work explores the complicated history of place, faith, and identity in the coalfields. In 2014, he founded the crowdsourced Looking at Appalachia project. rogermayphotography.com

MICHAEL O. SNYDER is a photographer and filmmaker who uses his combined knowledge of visual storytelling and conservation to create narratives that drive social impact. His photojournalism work has been featured by outlets such as National Geographic, The Guardian, and Washington Post. He is a Portrait of Humanity award winner, a Society of Environmental Journalists member, a Bertha Investigative Journalism fellow, a Pulitzer grantee, and a recent delegate to the United Nations Climate Conference. He lives in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains of central Virginia, where he is a resident artist at the McGuffey Art Center.

VANESSA CHARLOT is an award-winning photographer, filmmaker, lecturer, curator, and an assistant professor of creative multimedia at the University of Mississippi School of Journalism and New Media. Her photography commissions include the New York Times, Gucci, Vogue, Rolling Stone, New Yorker, Oprah Magazine, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Apple, New York Magazine, BuzzFeed, Artnet News, and Washington Post. Charlot was a recipient of the 2021 International Women’s Media Foundation Courage in Journalism Award, and she is an Emerson Collective Fellow. vanessacharlot.com

DEREK SLAGLE, PhD, MS, is an American documentary and fine art film photographer based in Little Rock, Arkansas, covering narratives primarily in the southern and midwestern United States. Slagle’s partnerships with nonprofits and government agencies led to documentation of conservation practices and research related to policy and administrative reforms. He has exhibited photographs broadly, in museums, publications, and exhibitions, and his forthcoming photography book focuses on derogatory toponyms on public (federal) land management. derekslagle.com

AUSTIN ANTHONY is a freelance photographer based in Bowling Green, Kentucky. A professional photographer for ten years, Austin has received national and international recognition for his work. He is available for assignments and willing to travel. austinanthony.com

BRANDON DILL has found a home in Memphis, Tennessee. When not planning road trips with his wife or picking vacant-lot mulberries with his daughters, he likes to make pictures. A regular contributor to the New York Times, Washington Post, and other publications, he is most at home partnering with Movement Journalism organizations helping to uplift stories of social justice and liberation. brandondill.com