Letter from Jesse on March 10, 2019:

Ana, What shall we plant next? Well . . . I will say I love the pansies year-round—momma used to grow squash & peppers in these pots next to our door at these apartments where we once lived. I’ve been thinking about greens a lot—I love honeysuckle & kudzu vines, they remind me of home. But listen, you can help me with my food growing choices—my thing is wanting people to eat out of my garden.

I think about Jesse’s words as I plunge my fingers into the soil of a raised garden bed in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward. The squash, peppers, and greens were harvested last month, and this morning I am finding space to plant carrot seeds between a robust patch of lemon balm and a sculptural object at the bed’s front. The sculpture is one of three in the garden, each designed by pouring mortar into molds shaped like a bed, a toilet, and a table. This “furniture” is modeled on the actual dimensions of the sole elements in the solitary confinement cell in which Jesse has lived for more than a decade, and from where he writes me letters about what he would like to plant in his garden on “the outside.” Jesse’s garden bed is one of several located in a small park tucked behind a high school, all of which are created in the standard size of a solitary confinement cell in US prisons: 6 × 9 feet. These garden beds are the first of artist and prison abolitionist jackie sumell’s Solitary Gardens outdoor social sculpture project, imagined through her twelve-year correspondence with Herman Wallace, who survived forty-one years in such conditions at Louisiana State Prison in Angola, Louisiana, until his release in 2013.1

On a given day in the United States, 2.3 million people are imprisoned, including an estimated eighty to one hundred thousand held in solitary confinement. The vast majority are male but incarceration rates for women and girls have been growing at twice that of men and boys over the past decades. These numbers include eleven thousand people in US territories, forty thousand youth, forty-four thousand in immigrant detention—3,600 of whom are children. People in prison and jail are disproportionately poor, and Native Americans, Latinos, and Black Americans are overrepresented. The criminalized population also includes 840,000 on parole and 3.6 million on probation. This system permeates US society so deeply that 113 million adults—that is, more than 50 percent of adults—have a family member who has been to prison or jail. The Gulf South states incarcerate at higher rates—in some cases, much higher—than the national average. These numbers tell the story of a punitive system, the reverberations of which are experienced through family separation, lost income and job opportunities, and the aftershocks of imprisonment on people’s physical and emotional well-being. This dire situation has drawn prison abolitionists to create a world free of prisons by focusing on the experience and knowledge of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people.2

The US prison industry depends on institutional bureaucracies, and those bureaucracies rely on public-private financing, the distribution of fossil fuels and the theory of mass incarceration, and extensive access to human labor—including 2.4 million people employed in police, corrections, or judicial jobs in the industry. This enormous infrastructure arose from the backlash against 1960s-era social and economic justice movements and is justified through a rhetoric of punitive governance that especially targets poor people, and Black, Brown, Native American, and gender nonconforming people. The Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) is so deeply embedded in US economy and society that it often feels impossible to imagine a world without it. And yet, this is precisely what Solitary Gardens asks of its participants.3

Solitary Gardens invites visitors to imagine a landscape without prisons by explicitly engaging the design of the modern American prison’s most dehumanizing element—the steel and concrete solitary prison cell. These gardens reinterpret this structure using plants historically connected to plantation slavery. Those of us on the outside create replicas to scale of the cells with carbon-neutral mortar composed of water, lime, and the Lower South’s three major cash crops produced under chattel slavery—cotton, sugarcane, and tobacco. These crops are now sometimes farmed by people imprisoned across the region for wages that range from four cents to one dollar per hour. In the empty spaces between mortar furniture, we plant herbs, flowers, and vegetables selected through correspondence with a Solitary Gardener—an individual imprisoned in solitary confinement—thus (re)imagining with them the confined, constrained space in which they live. Jesse refers to his cell as his “living tomb.”

A key feature of the Solitary Gardens is to animate the possibility of a prison-free landscape through plant-powered decomposition. The plants and “revolutionary mortar,” as sumell calls the material, ultimately overwhelm the garden bed’s structure, providing a visual deconstruction of the solitary confinement cell.

Solitary Gardens challenges the extractive methods of mass incarceration by emphasizing relationships—to one another, to plants, and to the land. Jesse reiterates to me in nearly every letter his desire to use his garden to feed and nourish others. He wants to know about the teas herbalists create with lemon balm harvested from his garden bed, and to see pictures of cucumber vine climbing up the replica of his solitary cell’s steel door. He uses the garden project to share memories of his native Gulf South ecology with me—the smell of flowers, the taste of fresh vegetables, and the image of his mother—none of which he has enjoyed since his solitary confinement began. And, he wants to know, “How are you, Ana? How is your spirit?”

The social interactions that arise from this plant-powered vision of abolition are evident in more than two years of participant observation and suggest that Solitary Gardens generates an affective economy that posits an alternative to the United States capitalist-scale PIC. Similar to anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s observations of the matsutake mushroom forests growing in the wake of scientific-industrial forestry in the Pacific Northwest, Solitary Gardens relies on “the interactions between scalability and its undoing.” In the remains of linear segmented space that organized planned plantation economies and engineered the standardized modular units required to turn people into prisoners, the gardens generate exchanges based on improvisation and reciprocity.4

Significantly, this economy relies on the revelation and circulation of stories that evoke personal experiences of harm and enclosure, and sometimes, of healing. In thinking about the generative power of this affective economy—of the work that shared feelings and emotions contribute to creating human subjects and social relations—I draw on scholar Sara Ahmed’s observation that “it is the very failure of affect to be located in a subject or object that allows it to generate the surfaces of collective bodies.” Affect both occupies and exceeds material form. In contrast to the “cruel optimism” cultural theorist Lauren Berlant describes of relentless messages urging modern subjects to be happy, optimistic, and striving in contexts that rely on increasing alienation, Solitary Gardens invites connection contingent on the recognition of profound harm. In this sense, the gardens illuminates prisoners’ ongoing efforts to envision plant life and social connection through letter writing, sketching a garden plan, stimulating memories of flower and color and scent. I am interested here in what I call affective attunements: people’s expressive interactions with the gardens as social sculpture. I propose these varied affective attunements show the promise that works like Solitary Gardens offer for mounting a politics of affect—in this case, a politics that sees abolition as a process of human connection rather than separation.5

People-Plant Imaginaries

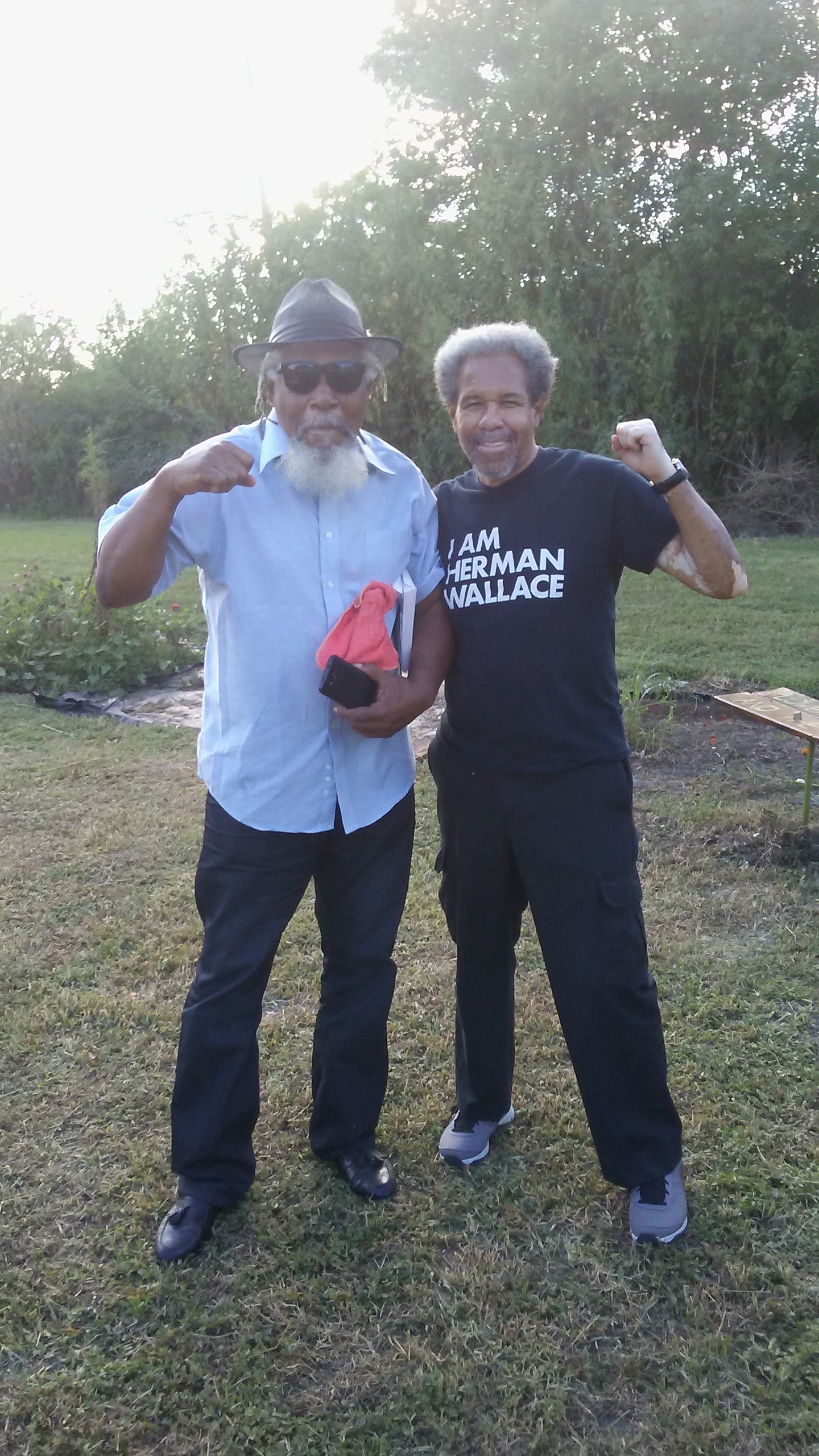

At the park’s opening in the spring of 2016, local housing activist and prison abolitionist Malik Rahim recounted the plight of prisoner-activists and solitary confinement survivors Robert King, Herman Wallace, and Albert Woodfox, dubbed the “Angola Three” because of their captivity in Louisiana State Prison on the former Angola Plantation. Rahim recounted how prison staff targeted the men in the 1970s because of their efforts to organize against the inhumane conditions at Angola. Their activism, like Rahim’s, was grounded in Black Panther principles that emphasized the right to land, bread, housing, clean air and water, education, justice, and peace. Rahim noted that the presence and strength of the Angola Three would always exist in the park as represented by trees anchoring three of the park’s four corners. The men selected their trees—King: cypress; Wallace: oak; Woodfox: magnolia—and they were planted first, before any of the Solitary Gardens were sown.6

Following Rahim’s dedication, local teacher and healer Nana Sula blessed the gardens through ceremonial drumming, reciting, and singing. Dressed in white, she moved slowly around the park, burning dried herbs as she walked and chanted. Through this ritual, she designated the park a healing space where the struggles of elders and the trauma of incarcerated people, their families, and their communities would be remembered to create a better world for younger and future generations.

Solitary Gardens invites the copresence of harm and healing. Replicas of solitary cells, the chattel slave crops, and the ravages wrought by the 2005 federal levee failures interface with nourishing rue, lemon balm, calendula, zinnia, pansy, sunflower, okra, watermelon, and mustard greens. Visitors are encouraged to reflect on how these tensions relate to their bodies and their lives. The emphasis on embodied multisensory practices to promote healing from physical, emotional, or spiritual harm has drawn a number of mental health practitioners to the project—including social workers, sports coaches, body workers, and dance therapists.

Mourning Confinement’s Reverberations

While the original Solitary Gardens site is comprised of seven beds in the Lower Ninth Ward, sumell has begun collaborations with other institutions across the city, installing a bed at Xavier University and a more permanent concrete and steel bed outside of the Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University. The project has also moved beyond New Orleans to Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, New York City, Providence, Houston, and Scotland, North Carolina. sumell’s Newcomb installation was originally part of the (Per)Sister art exhibit cocurated by formerly incarcerated Louisiana women and Newcomb museum staff. On a grey day in 2019, I took a group of my University of New Orleans students across town to visit the exhibit, where the Solitary Garden dedicated to incarcerated mothers staged the museum lawn. Visitors had to encounter it before entering the building. My students remarked on how far across the city we were—some of them had never been to this wealthy area of Uptown. They pointed out the curated lawns and massive live oaks, a stark contrast from their public university built atop a former naval base.7

After moving through the powerful exhibit organized around themes particular to women’s experiences with incarceration in Louisiana, I had the students gather outside of the gallery, next to the Solitary Garden. We needed some time to debrief about the exhibit’s sobering elements: a mother’s narrative of inducing her child’s birth prior to entering prison to serve her sentence (she chose to induce rather than risk the possibility of giving birth in prison where she would have been shackled during the delivery); the revelation that 80 percent of women in jail are mothers; the fact that without money for commissary, menstruating women wouldn’t be able to purchase tampons, an added expense for women prisoners. Only six students remained, and they all had something to say as we knelt by the garden bed filled with flowers planted for incarcerated women.

After hearing my students’ stories, I decided to share my own experience with mass incarceration. My son’s father had done time in a federal prison in Florida in the 1990s for a drug charge. Although we had been separated for several years prior to his incarceration, his contact with our son was sporadic, and his imprisonment when our son was seven years old only widened the gulf between them. In the years following his release, it became clear to me that prison was an experience from which he was still struggling to recover. Now I was reeling from his sudden and premature death at forty-eight years old. I had only just returned from his funeral in Chicago. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what imprisonment must have been like for him. Would the police who arrested him even have noticed him if he were white, like me, instead of Black like our son? He always had jokes. He loved making people laugh. He must have been terrified in prison.

I sensed that my students were surprised by this revelation. I had surprised myself; I typically don’t share such personal details with students. I hadn’t shared the information about the incarceration with anyone other than my closest family members and friends—I was afraid of the stigma it might bring to me and to my son to be affiliated with prison. But I was inspired by my students; I wanted to affirm their bravery as several had disclosed their families’ experiences with imprisonment. I was reminded of performance studies scholar D. Soyini Madison’s “performative witnessing,” whereby researchers exploring the impacts of inequality are present with their subjects in ways that “emphasize the political act (responsibility) of witnessing over the neutrality (voyeurism) of observation.” It felt impossible to remain silent. The students offered their support through gentle eye contact and murmurs of condolence.8

Weeks after the museum exhibit visit, I took my students to the Solitary Gardens site in the Lower Ninth Ward. I introduced the project’s tenets at Jesse’s garden and then invited my students to explore the other garden “cells” on their own before we met up in the middle of the park to write Mother’s Day cards to incarcerated women. The students peered into the garden beds, sniffing and touching, then most of them took seats on towels, jackets, and blankets spread across hot solarizing plastic and went to work decorating their cards and looking up poems and song lyrics on their phones to include in them.

Since March 2020, Jesse’s letters have registered how the COVID-19 pandemic has brought further restrictions to his confinement. He tells me that prisoners in solitary are now no longer permitted even the one hour per day outdoors alone in the “yard,” where one can see the sky in between walls so high they block daylight from hitting the ground at any angle. “This world of tombs is a unique hell,” he writes after describing how some of the prisoners have become so distressed by the added COVID restrictions and concerns that they are constantly yelling profanities and fear mongering from their cells in his tier. He is trying to maintain a sense of sanity by studying language (he is learning Arabic) and making drawings for his wife and stepdaughter.

I write to him of the garden, tell him that planting continues. I include photographs of his garden in my letters. He is only permitted to receive them printed in gray scale, and letters must be written or printed in black ink on white paper. No color allowed. A letter from Jesse on June 9, 2020, reads:

These images from the garden are blessings that allow my heart [to] breathe in the green beauty of natural life. I smell the South! I feel the heat! The cold blankness of this tomb is left behind as I stare into these images, I pray over the hands that dug into this soil, maybe the hearts did understand the impact their work would have, but I sincerely struggle to imagine they knew of these tears that would fill my eyes—I’d been pacing this tomb in a state of woe & inner chaos for the past several movements of time when these merciful images arrived to hold me in their living green-ness—All the noise of the vulgar screams & clanking steel & recycling air & concrete & human suffering faded. I was gifted a silently peaceful moment there in New Orleans.

Jesse’s garden is more than a thousand miles away from his “tomb.” He knows that none of us can truly understand what he feels upon receiving news and images of the garden and yet he still makes the effort to convey this to us poetically. He insists on his living human ity even while reminding me over and again that he is doing so from a crypt.

Scholar-activist Angela Y. Davis writes that “abolitionist approaches ask us to enlarge one field of vision so that rather than focusing myopically on the problematic institution, we raise radical questions about the organization of larger society.” Solitary Gardens invites us into such inquiries through the senses. The stories shared in letters and at the garden sites emerge from affective attunements to the garden’s broad themes of harm, containment, isolation, dehumanization, restoration, invitation, nourishment, and healing. These themes provide the improvisational material for individuals to connect their histories to the (re)generative world of plants, in often spontaneous and unpredictable ways, to acknowledge the horrors of historical and present-day human-made suffering and also to embrace the pleasures of connecting to plant life and to one another. New Orleans serves as the southern seedbed propagating Solitary Gardens’ anti-incarceration principles throughout the United States.9

What if we looked more often to plants to enlarge our understandings of gendered and racialized bodies, of harm and healing? What if we started listening to incarcerated people and their families? What if we treated them as the experts on their own experiences, folks who can meaningfully contribute to address the problem of mass incarceration? What if we supported people’s efforts to return to land and make their own meaning from such returns?

In late December 2020, a dream of Jesse’s became reality: his wife, stepdaughter, mother, sister, sister’s husband, aunt, uncle and cousin traveled from Northern California, Florida, and Mississippi and gathered together to visit his Solitary Garden in New Orleans’s Lower Nine. The day was sunny and warm and each family member was able to place a plant in Jesse’s garden. “It was a beautiful thing for my family to visit the garden,” he wrote on January 31, 2021. “They experienced it spiritually. Lily found several four-leaf clovers, she kept one & left me the rest, Little Sweetie! My mom & aunt took some greens to cook. They all took away a sense of union—Putting your hands in the soil will give you this sense of union with life, it will show you God. That’s the thing about the project. It is interactive. You reach down & feel it.”10

Jesse, along with tens of thousands of people held in solitary confinement today, cannot reach down and feel soil or plantsor touch a tree. Solitary Gardens offers a vision of a country where such confinement is unimaginable. In prioritizing relationships governed by care and reciprocity among incarcerated people, nonincarcerated people, and the world of plants, the gardens provide a template for a landscape without prisons.

Ana Croegaert is a sociocultural anthropologist and the author of Bosnian Refugees in Chicago: Gender, Performance, and Post-War Economies (2020). Her latest research explores how cultural production relates to the social significance of urban change. Ana received her Ph.D. from Northwestern University and is currently a research scientist at the Field Museum in Chicago where she is lead ethnographer with the newly established Pandemic Collection.NOTES

- Solitary confinement is officially referred to as “Closed Cell Restriction” or CCR, in US prisons. Jesse has lived in a CCR cell for nearly fifteen years at the time of this writing, first at Parchman and now at the Federal Supermax Prison, ADX in Florence, Colorado. The CCR prisoners at his facility are periodically rotated to the next cell over. Herman Wallace had terminal cancer when he was released from Angola and died several days later. The artist jackie sumell does not capitalize her name.

- Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas in “Discover Your State,” Prison Policy Initiative, last accessed November 9, 2021, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/; adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2017); Mariame Kaba, Missing Daddy (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019). The author adrienne maree brown does not capitalize her name. Official counts of persons in solitary confinement are lower, at an estimated sixty-eight thousand. But this statistic underreports because it excludes people held in confinement for less than fifteen days—the length of time deemed to constitute human rights abuse as specified by the Mandela Rules—and excludes those held in solitary in jails and other detention sites. Joshua Manson, “How Many People Are in Solitary Confinement Today?,” Solitary Watch, January 4, 2019, https://solitarywatch.org/2019/01/04/how-many-people-are-in-solitary-today/. Women and girls comprise 231,000 of those in prisons. Aleks Kajstura, “Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2019,” Prison Policy Initiative, October 29, 2019, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2019women.html.

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Roger Lancaster, Sex Panic and the Punitive State (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011); Marie Gottschalk, Caught: The Prison State and the Lockdown of American Politics (Princeton University Press, 2015); Emily Widra, “Tracking the Impact of the Prison System on the Economy,” Prison Policy Initiative, December 7, 2017, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/12/07/econ_update/.

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2015), 37–43.

- Sara Ahmed, “Affective Economies,” Social Text 79, vol. 22, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 117–139; Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); Nigel Thrift, “Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect,” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86, no. 1 (2004): 57–78. My thinking is indebted to Katherine McKittrick’s invitation to engage the historical specificities of plantation geographies and be attentive to people’s efforts to evade and shape the cruel contours of “the slave plantation and its attendant geographies (the auction block, the big house, the fields and crops, the slaves quarters, the transportation ways leading to and from the plantation . . . [through] alternative mapping practices . . . fugitive and maroon maps, literacy maps, food-nourishment maps, family maps, [and] music maps.” Katherine McKittrick, “On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place,” Social and Cultural Geography 12, no. 8 (2011): 947–963. McKittrick carefully notes that she is not positing an equivalent relationship between chattel slavery and mass incarceration.

- The official conviction of the Angola Three, based on allegations that they had killed a prison guard, was shown to be faulty after numerous appeals. Robert King was jackie sumell’s original teacher in her abolitionist endeavors after his conviction was overturned in 2001. He had served twenty-nine years in solitary confinement. Herman Wallace and sumell corresponded for fourteen years during which they developed the plans for “Herman’s House”—the house Wallace envisioned living in upon his release. jackie sumell and Herman Wallace, The House That Herman Built (Stutgart, Germany: Edition Solitude/Reihe Projektiv, 2015). Wallace endured forty-two years in solitary confinement before he was exonerated and released on humanitarian grounds on October 1, 2013, and passed away three days later after a long battle with cancer. Albert Woodfox endured forty-three years of solitary confinement before his conviction was overturned in 2015 and he was released in 2016, a journey he recounts in his book, Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement. My Story of Transformation and Hope (New York: Grove, 2019).

- Cocurators included Syrita Steib-Martin, Dolfinette Martin, Monica Ramirez-Montagut, Laura Blereau, Megan R. Flatley, Andrea Armstrong, Operation Restoration, and Women With A Vision. (Per)Sister opened at the Newcomb in the spring of 2019 and at the time of this writing is installed at the Ford Foundation Gallery in New York City. “Per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana,” Newcomb Art Museum, accessed November 9, 2021, https://www.persister.info/about.

- D. Soyini Madison, Acts of Activism: Human Rights as Radical Performance (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011). Madison is drawing on the work of her mentor, Dwight Conquergood, and his method of “co-performative witnessing.” Dwight Conquergood, “Performance Studies: Interventions and Radical Research,” TDR 46, no. 2 (Summer 2002): 145–156.

- Angela Y. Davis, “Why Arguments against Abolition Inevitably Fail,” Medium, October 6, 2020, https://level.medium.com/why-arguments-against-abolition-inevitably-fail-991342b8d042; LEVEL Editors, “Abolition for the People,” Medium, October 6, 2020, https://level.medium.com/abolition-for-the-people-397ef29e3ca5.

- “Lily” is a pseudonym.