When I describe Jesmyn Ward’s writing to people, I say, “Her writing leaves me with brittle bones.” Originally from the Gulf Coast community of DeLisle, Mississippi, Ward is unapologetically steeped in a southern Black literary tradition that amplifies the complicated realities of being Black in the South, wrapping her characters in a warmth and honesty that few other writers can match. Among an ever-growing list of accolades, Ward is a MacArthur Fellow and two-time National Book Award winner for her novels Salvage the Bones (2011) and Sing, Unburied, Sing (2017). Her writing voice is beautifully gentle yet commanding across a variety of genres, including fiction, essays, and a memoir, Men We Reaped (2013).

Ahead of the release of her latest novel, Let Us Descend, Ward sat down with me to discuss the importance of the Gothic in writing about the Black South, how grief is central to her writing, and why writing helps her confront and understand Mississippi’s racially turbulent history.

REGINA N. BRADLEY: This issue deals with the Gothic South. Usually when we think about Gothic in the South, it is white and male. What role do you feel the Gothic plays in how you tell stories about being Black in the South?

JESMYN WARD: For me it always goes back to the beginnings for us as Black southern people. It always goes back to enslavement, and in relation to white southern writers, for me, that’s the dark heart of everything. I think they tend to write around it. I feel like Black writers, specifically Black southern writers, write more towards it. Maybe because we had less. There was no avoiding it for us. We have always lived with the real ramifications of slavery for hundreds of years. I don’t feel like we could write around it. When I think about my own fictional work, there was a hint of the Gothic in Salvage the Bones, but I think it became more of a real presence in Sing, Unburied, Sing. And then definitely in my most recent work, Let Us Descend. Even when I think about Men We Reaped, my memoir, it was a presence there too. For me, the Gothic comes out in wrestling with that darkness, wrestling with trauma, wrestling with grief, wrestling with loss, wrestling with this idea that there is more to the world than what we see on the surface. I’m thinking not only about history, but the supernatural, things that you can’t explain. That has also been with us since the beginning.

RNB: In your first novel, Where the Line Bleeds, you get traces of the Gothic in your dealing with Christophe and his descent into addiction. Then you see it a little bit more in Salvage the Bones with Esch and her relationship to China, for example. Then you really just bust the door wide open in Sing, Unburied, Sing. I know you did some research for that book because of the way that you described Parchman Farm. The descriptions of it are so vivid and significant. Can you talk about why the Gothic was useful in Sing, Unburied, Sing? There’s a tangible darkness, a dread that southern Black folks can’t avoid because, on the one hand, white people don’t want us to confront the idea of enslavement. They want it to be like, “That happened hundreds of years ago. You don’t have to worry about that shit no more.” But it hits me every day.

JW: When I was writing Sing, Unburied, Sing, it’s almost as if that darkness, that Gothic aspect of it, had to be a part of that story. Partly because I was so horrified by the reality of what had occurred that I had to introduce that element into it. I didn’t know anything about Parchman at all. I mean, I had some relatives who had been there whom I talked to about it, and they told me their stories about what it was like for them to be incarcerated, but I didn’t know anything about the history of the place. I mean, I knew the conditions in the present were terrible, but I didn’t really know anything about how that place had come about or what it had looked like in the past.

So I started to read and research. This was before the Thirteenth documentary on Netflix came out. I think that documentary exposed a lot of people to the fact that, back in the 1930s and 1940s, kids were sent to Parchman. Twelve- and thirteen-year-old kids charged with stupid things that weren’t really crimes, just ridiculous things like loitering, and basically being reenslaved, because Parchman was a plantation.

I grew up in Mississippi and went to school here. I left for college, but for half my life I attended public school. For most of middle and all of high school I went to a private school on scholarship that gave me what would be considered a good public-school education in another state. There’s so much about Mississippi’s history, especially when it concerns Black people, that I was not taught, that I did not learn in school. I just remember when I read that young kids were sent to Parchman and some of them died, I was so horrified that I went looking for the information, and looking for it was the only reason that I found it. I was so angry and hurt and aggrieved that they had been erased. All that pain and suffering. Their lives were erased because that fact has been erased.

I believe that erasure is part of the reason that this effort to ban books by Black people, by people of color, by queer people, makes me so angry. Y’all already did it. It’s already been done. So much of what we should know about to get a full understanding of American history has been erased and withheld from us. What more can you erase?

I felt so awful for the children like Richie, the character in my book, that his life and the lives of kids like him had been erased from history. I thought, I want to write him back into the present. I wanted that child to have the kind of agency that he had been denied in life, to act and have a certain amount of power and freedom in the present moment that he hadn’t had in the past. The only way that I could figure out how to do that was by making him a ghost. That’s why I introduced that Gothic element into the story, by necessity.

RNB: Your use of the Gothic and haunting allows for stories to be told that otherwise would remain on the margins, be whispers of stories or snatches of history. I also think something representative of your use of the Gothic is the way you describe the landscape, the way you describe nature. It’s so intentional. Why pay so much attention to the surroundings of the characters? Your settings become characters themselves.

JW: I think it’s something I’ve intuitively felt my whole life but didn’t explicitly think about until I started writing about Hurricane Katrina. I wrote an essay a long time ago about Hurricane Katrina, “We Do Not Swim in Our Cemeteries,” that was published in Oxford American.

That’s one thing about Kiese too. He grew up with his grandmother. He grew up in this place that’s very rooted in extended family and community. We both grew up in these environments—I could cross the street and walk about a hundred yards up and I’m at my great-grandparents’ house. A lot of the time I spent with them was sitting on the porch listening to them talk, and they’re telling stories. So even though I may not have been educated in school about what it was to be Black in Mississippi in the 1930s, I know it from them. The past doesn’t feel very far removed from us. The past feels like the present. When we’re writing about what it means to be Black in Mississippi, when we’re creating our characters, the past is very present in our work with all its attendant traumas and hardships and joys, all the things that make life worth living here. We are writing from places where people didn’t leave. I have relatives who went to Chicago and California, who were part of the Great Migration, but Black Mississippi writers like me and Kiese, we’re writing from people who chose not to leave.

RNB: I have another question about legacy. I put you in conversation with writers like Mildred Taylor, Margaret Walker, and Richard Wright. Does it bother you that the first writer people think of when they talk about your writing is William Faulkner? I rant hard about this on Twitter. I’m like, “She’s not the heir to Faulkner. She is the first of her name, like Game of Thrones.” How do you feel about that?

JW: I love that you say that, but right now, it doesn’t bother me much. I love Faulkner’s prose because of the way he wrote about the landscape of the South, the vivid power of his imagery, and the way he used rhythm in his prose. I just love those aspects of his writing so much. They affect me in the way that good poetry does. In a way, I feel like it scrambles my critical response. And I think that’s just because I was a reader before I was a writer. Prose like that, poetry like that, cuts off my critical faculties and I revert to being in awe. That kind of awe you get when you’re just a reader and you’re being swept up in something. It doesn’t bug me as much as it should. But whenever he writes about Black people, southern Black people, there’s no depth there. And from the Faulkner that I’ve read, that shallowness, that shallow characterization, bugs the shit out of me.

RNB: Yes! I can see the influences, but the way he handles Black folks, they are just on the side. That’s never the case with your writing. We’re always front and center.

JW: Right. And it’s interesting to me that people can’t see that. I read The Sound and the Fury years and years and years ago. But I remember in that novel specifically, even when the narrative is closely aligned with the Black characters, even when you’re with them in a room and they’re talking with no white characters around, they aren’t real people. I remember feeling that very strongly in that moment. Yes, they’re center stage there; you are right there with them. But they aren’t real people. They aren’t my grandparents.

RNB: Faulkner’s story “A Rose for Emily” is peak Gothic for me, but the one question that I have had about that story since I was nineteen, when I first read it, is about the manservant, Tobe, the Black dude who answers the door. When the townspeople be like, “We’re here for Miss Emily,” he just walks out and doesn’t say anything. I want to know what he was thinking on the way out. All Faulkner says was that he opened the door, he walked out, and he didn’t say nothing to nobody. I’m like, this man is waiting to go talk to his people. I need a short story about when he got home. Faulkner could never give me that [laughs].

I want to go to your memoir, Men We Reaped, which I teach almost every other semester. It is ridiculously good. I think about those moments where you talk about your brother and your friends, how you weren’t there in the moments leading up to when they passed but you describe their deaths. It’s almost like an obituary. So I’m wondering: how is that a reflection of the southern Black Gothic? Because I feel like it was a way for you to gain closure. But also, even with all of their flaws, these men were still loved and cared about. The way you write about them showed that they were loved and cared for and followed in a tradition of southern Black grieving. What connections are there between grieving and the Gothic in your writing?

JW: I don’t know if I can answer that question. One thing that I was doing when I was writing about what it might have been like when each of them died—especially in the chapter with my brother—was that there has to be something more, something more than the terror, something more than the dread, something more than that impending darkness, that impending pain, that transition leading up to each of them dying.

I was trying to expand those moments beyond this narrowed point where their deaths occurred. All the options regarding what could happen sort of narrowed, narrowed, narrowed, narrowed. So at the same time that I was narrowing it down action-wise, I wanted to expand them in terms of the supernatural, as well as the weight of history that also led to this moment. I was trying to depict all of those things as well.

In a way, I think I wanted to do that because I was trying to reckon with the fact of their deaths and reckon with the fact of that traumatic event. But at the same time, I wanted to acknowledge that there’s more that exists. Even in that terrible moment, there’s more. Without that acknowledgement of more, it’s very hard for me to understand and for readers in general. People coming to this moment need to understand how we survived and how we made it through. And how we continue to survive and continue to make it through.

Working on Let Us Descend has clarified some things for me, especially around trauma: how Black people reckon with trauma, how we reckon with grief, and how we reckon with loss. What makes it possible for us to continue to not just survive but thrive in spite of it?

I’m glad that I’m here and that I have written that specific book. Because writing that specific book, which is so much about grief and surviving, is also about finding your way through very hard, very traumatic events to this place where you can thrive and retain a sense of self. You can build, find family, and do all these things that may seem impossible even in the face of tremendous pain, tremendous trauma, and tremendous grief. As you know, I’ve been struggling with a fresh grief for the past three and a half years. I think it has helped clarify—though not fully—some things for me. It made it easier for me to understand how we continue to make a way out of no way and how we continue to wrestle with the darkness at the heart of this country and still make something beautiful out of it.

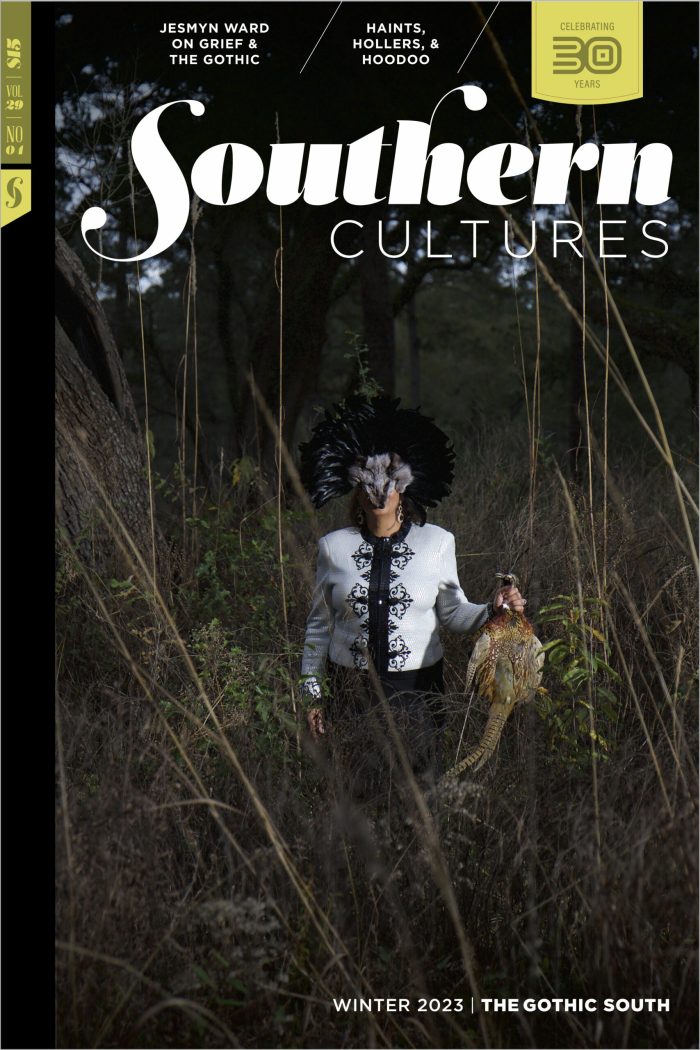

This conversation is from the Gothic South issue (vol. 29, no. 4: Winter 2023).

Jesmyn Ward has received the MacArthur Genius Grant, a Stegner Fellowship, a John and Renee Grisham Writers Residency, the Strauss Living Prize, and the 2022 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. She is the first woman and first Black American winner of two National Book Awards for Fiction for Sing, Unburied, Sing (2017) and Salvage the Bones (2011). She is also the author of the memoir Men We Reaped, and the novels Where the Line Bleeds and, most recently, Let Us Descend.

Regina N. Bradley is a writer and researcher of the Black American South. A former Nasir Jones HipHop Fellow at the Hutchins Center, Harvard University, she is associate professor of English and African diaspora studies at Kennesaw State University and coeditor of Southern Cultures. Dr. Bradley is the author of Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South. She can be reached at redclayscholar.com.