One thing I did not have on my 2020 Bingo Card was being sonically minstrelized by a white man. A friend asked me to write a short reflection about OutKast and their connection to Afrofuturism for a special issue of a fiction magazine featuring writers of color. My piece talked about the Kast’s use of sound as a tool of freedom and experimentation, whether here in the South (Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik) or out in space (ATLiens). It was the sole nonfiction piece in the issue. The magazine’s customary practice was to have a voice actor read and dramatize the pieces as complements to the print versions. The actor hired to voice the special issue—reading the stories of Black folks, Brown folks, and other writers who ain’t white—was a white man. Wayment nie. My essay started with the sentence “I’m a southern Black woman raised in the long shadow of the Civil Rights Movement.”

Bay-beh. This man butchered my shit.

He sounded like Colonel Sanders and Miss Cleo had a throat baby wrapped in a tattered Confederate flag left on the doorstep of Joe Black. He read the title, “Da Art of Speculatin’,” in a faux-Jamaican accent and, by the end of the reading, sounded like Uncle Mammy. His voice was shallow, clipped with vinegar instead of dripping with warm honey and bourbon. He haphazardly emphasized vowels and dropped g‘s to sound more “authentic.” He thought southern Black folks were exaggerated and stretched themselves thin to fit into a story that didn’t center their truest selves. This man’s voice was not honest. It was not warm and reflective of porch talk, where it was common to talk about music and grief, and crack jokes to work through the grind of daily life. His performance of my words lacked love that he ain’t never experienced from southern Black folks. His performance of southern Blackness pulled from communities that didn’t exist nowhere except his own lackluster imagination. Mispronounced word after mispronounced word pushed me further and further into myself. I hit up my friend on Facebook ready to throw metaphorical and physical hands.

I posted a snippet of the voice actor mocking southern Black women to my social media accounts. Hell broke loose. Some said they didn’t understand my outrage. Others called the man a racist. Even more folks in the writing industry called out the magazine’s hypocrisy, as it was at one point known to champion diversity and be more inclusive of the types of writers and stories it published.

Of course I heard from the editor and the voice actor involved in the minstrelsy.

Of course the actor and editor were deeply ashamed.

OF COURSE the actor proclaimed his innocence because is it really an apology from a white person being racist if they don’t claim they were not racist? He explained how he didn’t want to break contract and reach out to ask if someone else could read my essay. But even if there was absolutely no one else to read my work—it’s impossible to find Black women doing narration, apparently—there was still a way to avoid all the drama. There was the unpursued possibility of reading my essay in his regular shmegular voice to sonically register the piece was nonfiction, to give it the respect it (and I) deserved, to sound my sincerity and celebration of these important artists. But nah. Instead, he dramatizes the reading so it doesn’t “stand out from the others” by creating a Gone With the Wind and Song of the South mashup.

The voice actor may have expressed shame and regret but it was cricket knee high ’cause he was shamed and regretted being called out. I never responded to the multiple apologies. I wanted those apologies to hang out there, awkward and bone dry, like the minstrelized performance of my southern Black womanhood. My anger was generational, sweeping, and fast-moving like a flooding river. I felt a shame and rage I hadn’t felt ever in my life. His voice sat smugly in the center of my brain, taunting me and hindering me from writing for months. I read my essay repeatedly, looking for the lines that could be misinterpreted. Above the storm roaring in my head, I heard the southern Black women that lived in my spirit from the past and present sucking their teeth in disgust. “We tied of it, nie. The erasure,” they said.

I live by the doctrine that my voice is layered with the favor, expectation, and labor of the Black women who came before me. My voice is where we communed and laid flat what it meant to be a Black woman from the South.

I refused to be erased. I refuse to be erased.

The sonic blackface incident reinvigorated my interest in race and sound in the South. Quiet as it is kept, sound is a key signifier of southernness. It is foundational to understanding southern life and culture. A grandmother’s shushing of everyone in the house so that the Lord can do His work during the thunderstorm. Biscuits or corn bread softly thudding against a plate to sop gravy or pot likka on a Sunday afternoon. The stomp of feet on a freshly swept porch.

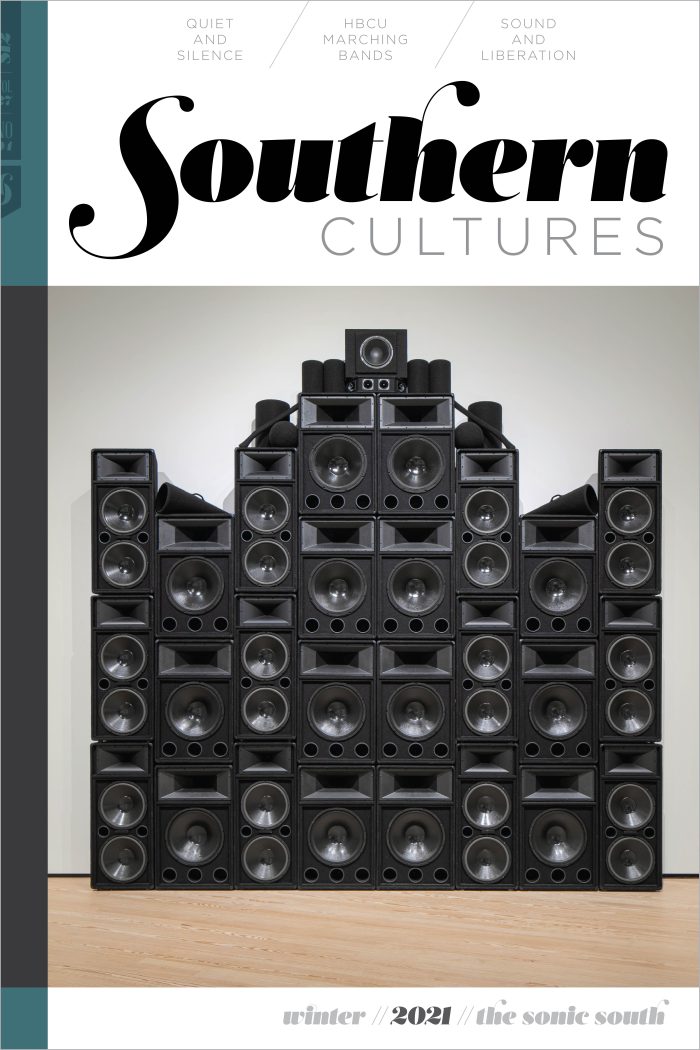

In popular culture, the sonic “South” is comprised of familiar and often stereotypical touchstones of performative southernness: the sprawling drawl of Foghorn Leghorn, the twang of tuning a banjo, or the Sparta police department from the television show In the Heat of the Night. The Sonic “Souf” is the hip-hop South, the one where the vibrations from a trunk full of subwoofers and bass dot the air like braille. The Sonic Souf is also where corrections to the narrative about Black southerners can be made without judgment and entanglements of respectability or generational expectations. Sound is where the South can be its most complicated and unapologetic being, where it can boast its plurality and multiple communities.

Still, that multiplicity is not always positive or filled with lighthearted intentions. Southern sounds plant themselves in our imaginations and grow wildly, unwieldy, often clamoring together without explanation. The yell of white supremacists chanting “You will not replace us” in 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, juxtaposes the calm assurance of civil rights protestors singing “We shall overcome” in 1965 in Selma, Alabama. The sonic signals comfort and legibility as quickly as it alerts us to discomfort and illegibility.

Sonic southernness is celebrated as dominantly white and all-encompassing. For example, country music’s wide appeal and musicality is rooted in a perception of whiteness rather than acknowledgement of the Black singers and instrumentalists who contributed to its origins. Even today, there are calls for country music to “stay pure” (read white), most recently in the rejection of Lil Nas X’s song “Old Town Road” and the accusation he desecrated country music. White southerners too loudly boast of a Confederate heritage but are uncomfortable acknowledging the Confederacy’s reliance on slavery. The silence around slavery is both historical and intentional: we do not know the daily soundscapes of enslaved people but also are discouraged from asking questions about slavery because it humanizes people who were supposed to be property. We have a fragmented understanding of slavery’s interiority but sound allows us to experiment and ask “what if?” We engage in sonic archaeology—something akin to Toni Morrison’s theorization of “literary archeology”—by using sounds from the present to gain a better understanding of the past. We imagine the soundscapes we don’t have access to and often plug in the sounds we are familiar with to connect the dots. For example, we use hip-hop to score television shows like Underground and movies like Django Unchained to amplify the rage, coolness, and trauma that enslaved people faced daily. Sound becomes a space to make the illegible experiences of the past more legible, visceral, and hard-hitting for a contemporary audience, a way to mine the resonances and connect the threads of experience.

The South, in all its varied manifestations, is a monument of eternal nostalgia. Sounding the South is an opportunity to reckon with and break through this reflexive fondness for the past and work the region’s social landscape for what it is: snapshots of real and imagined experiences that show a much more complex picture than a stereotype of backwardness.

The Sonic South issue theorizes how sound detaches southernness from the sanitized and whitewashed background that the region is frequently assigned. Antron D. Mahoney and Matt Sakakeeny spend time with the impact of HBCU bands on the South. Mahoney beautifully subverts and questions the role of HBCU bands and dance lines in expressing queer Black masculinity. Sakakeeny profiles LeBron Joseph, an HBCU band alumnus and band instructor for the program The Roots of Music. Sakakeeny centers Joseph’s band training as a touchstone for him, exploring how Joseph’s experience as a southern Black man informs how he teaches Black boys and girls in post-Katrina New Orleans.

Continuing the throughline of how sound troubles race and identity in the South, Abigail Greenbaum considers the impact of Black laborers, civil rights organizers, and R&B music on folk singer-songwriter Gram Parsons during his childhood in Waycross, Georgia. Black educators Kristofer Graham, Jessica Peacock, Christina Spears, and Keisha Worthey thread the significance of silence and quiet through a roundtable of essays that explore the long legacy of Black pedagogy in the South. Kristin Gee Hickman’s essay on the use of the University of Mississippi’s nickname “Ole Miss” moves us from pedagogical silences to linguistic oppressions, providing a refreshing sonic framework for understanding slavery’s legacy in Mississippi.

Finally, the issue boasts two amazing photo essays by Monica Moses Haller and Joanna Welborn. Haller offers a unique and fascinating photo/audio essay about how the sounds of the Mississippi River overlap with her and her family’s personal history. Welborn’s photo essay visualizes her Deaf family members’ experiences building a homestead and community on Windy Gap Road near the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina.

Ultimately, this issue of Southern Cultures showcases the sonic South as vibrant while cracking out truths like arthritic joints. Some of those truths, quiet as many would like them to remain, find ways to stomp and sing and gurgle themselves into existence.

Regina N. Bradley is a writer and researcher of the Black American South. A former Nasir Jones HipHop Fellow at the Hutchins Center, Harvard University, she is associate professor of English and African diaspora studies at Kennesaw State University and coeditor of Southern Cultures. Dr. Bradley is the author of Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South. She can be reached at redclayscholar.com.