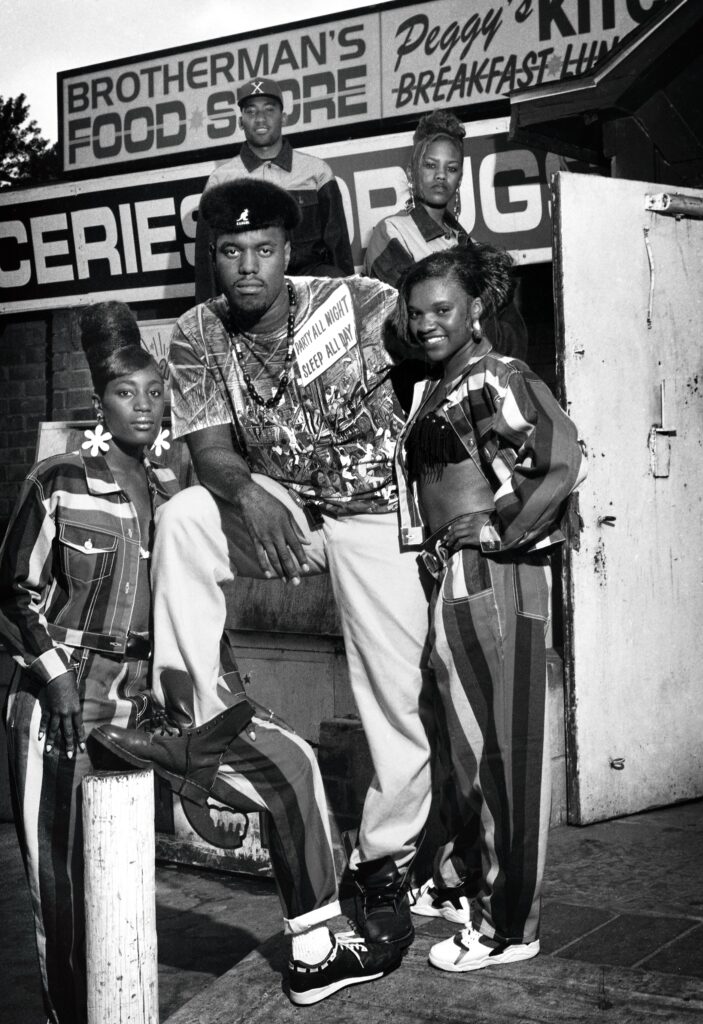

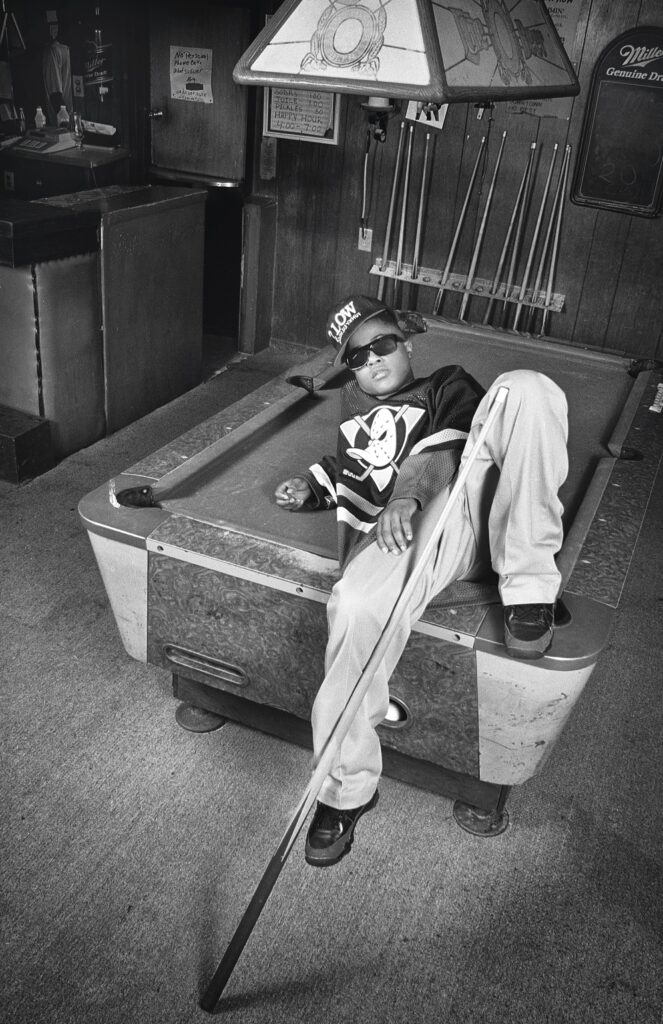

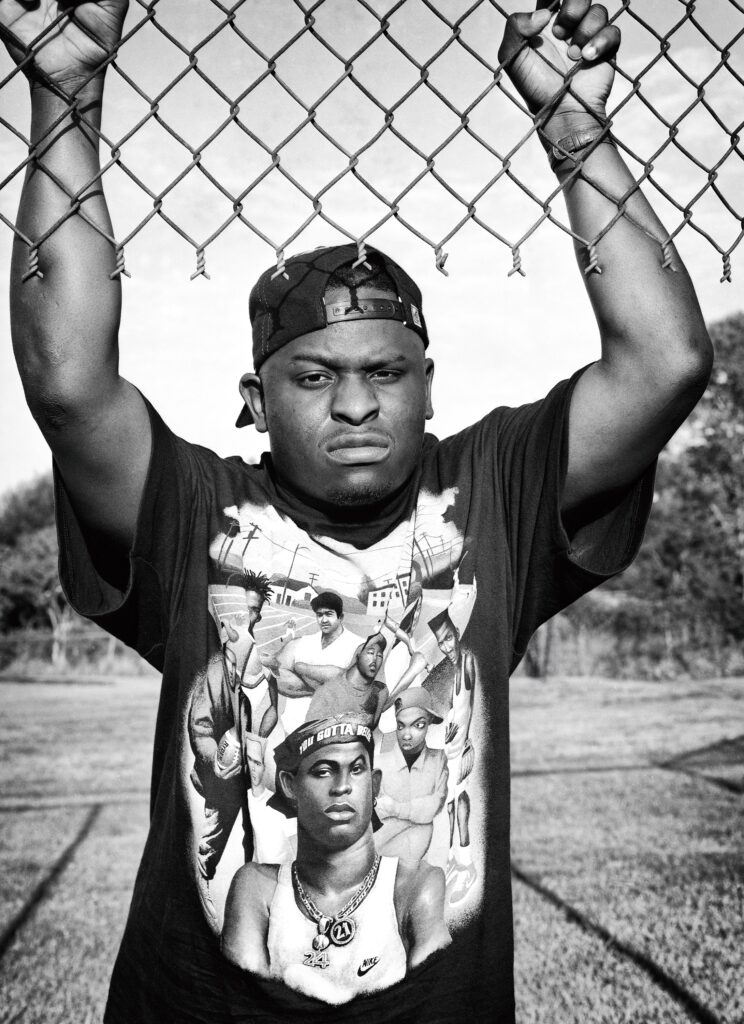

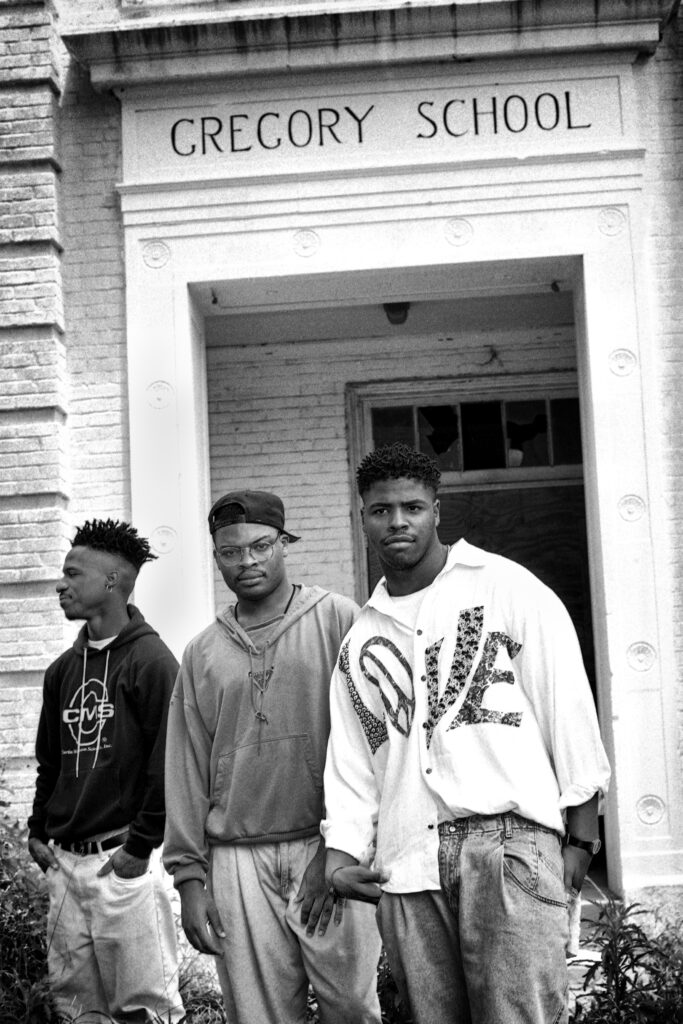

“I didn’t fully realize that I was creating a visual archive of a time when hip-hop was deeply rooted in localized lived experiences.”

I began my career in photography in Houston, a city where hip-hop was steadily emerging onto the national stage in the 1990s. What started as an underground movement gradually gained momentum, and by the early to mid-’90s, Houston had rooted itself as a significant force in the genre. This era serves as a vital memory practice, preserving southern hip-hop’s physical and cultural landscapes before it evolved into the digital age.

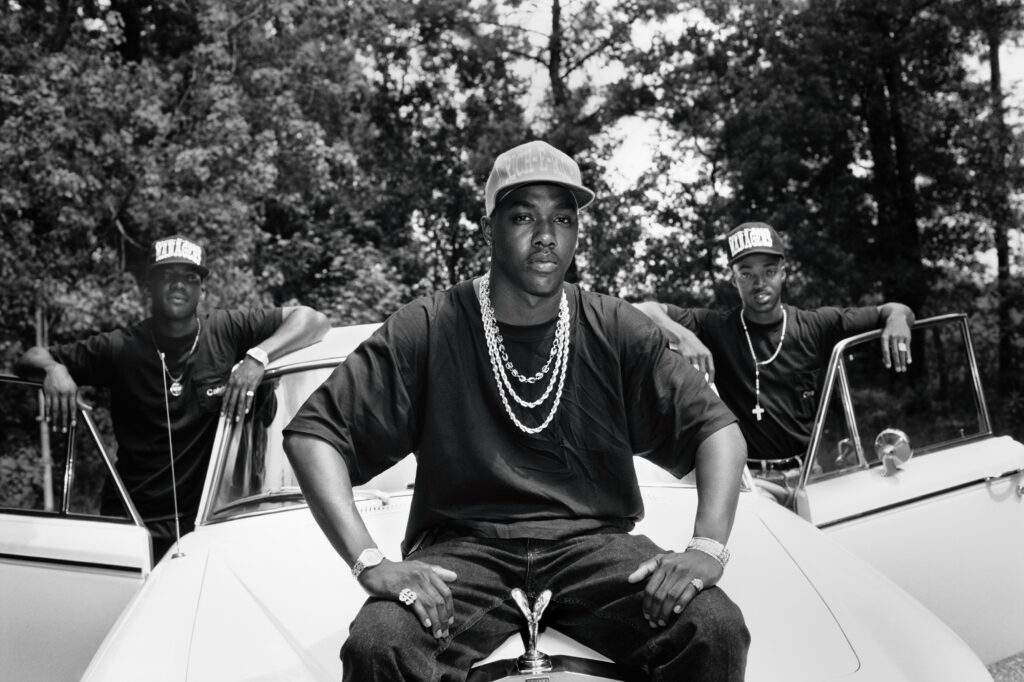

As a young and curious photographer trying to understand the culture, I started photographing promotional portraits for independent labels of aspiring rappers who saw hip-hop as a way to transcend their environments and create a better future for themselves and their families. My images soon caught the attention of the creative director at Rap-A-Lot Records, who gave me the opportunity to photograph the rapper Scarface, formerly of the Geto Boys, while he was working on his new album, The Diary. The album premiered in 1994 and is considered one of his most influential albums, featuring tracks like “I Seen a Man Die” and “Hand of the Dead Body.” As a solo artist, Scarface became known as the philosopher of the streets, and his lyrical sound became deeply emotional through his poetic storytelling and cinematic narratives. He influenced legends like OutKast, T. I., and Jeezy, which made Atlanta a dominant force in amplifying the southern rap explosion.

During this golden era, I didn’t fully realize that I was creating a visual archive of a time when hip-hop was deeply rooted in localized lived experiences. These spaces, once raw and unfiltered, have since become cultural artifacts, embodying the storytelling tradition that defines southern hip-hop. Unlike today’s rapid, algorithm-driven circulation of music, these images resist the short-lived nature of the digital age. While social media and streaming platforms often shape hip-hop memory, these portraits serve as a reminder of a pre-Internet hip-hop culture—one built in the streets, through face-to-face rap battles, and within physical spaces that have since faded. This shift has redefined how the culture is archived, remembered, and reshaped in real time.

As southern hip-hop has dominated the global mainstream, these portraits are a testament to its origins, ensuring that this movement and its artists are remembered—not just as a genre but as a powerful rooted cultural practice that continues to evolve while carrying the weight of its past.

Trinity Garden Cartel, Don’t Blame It On Da Music, 1994.

Sheila Pree Bright is a lens-based artist whose work redefines how we see contemporary culture. She is the creative force behind the acclaimed book #1960Now: Photographs of Civil Rights Activists and Black Lives Matter Protests, a powerful visual bridge between past and present movements.

Header image: